Tan Jie-sheng: a success story of one transnational Cantonese merchant in Korea

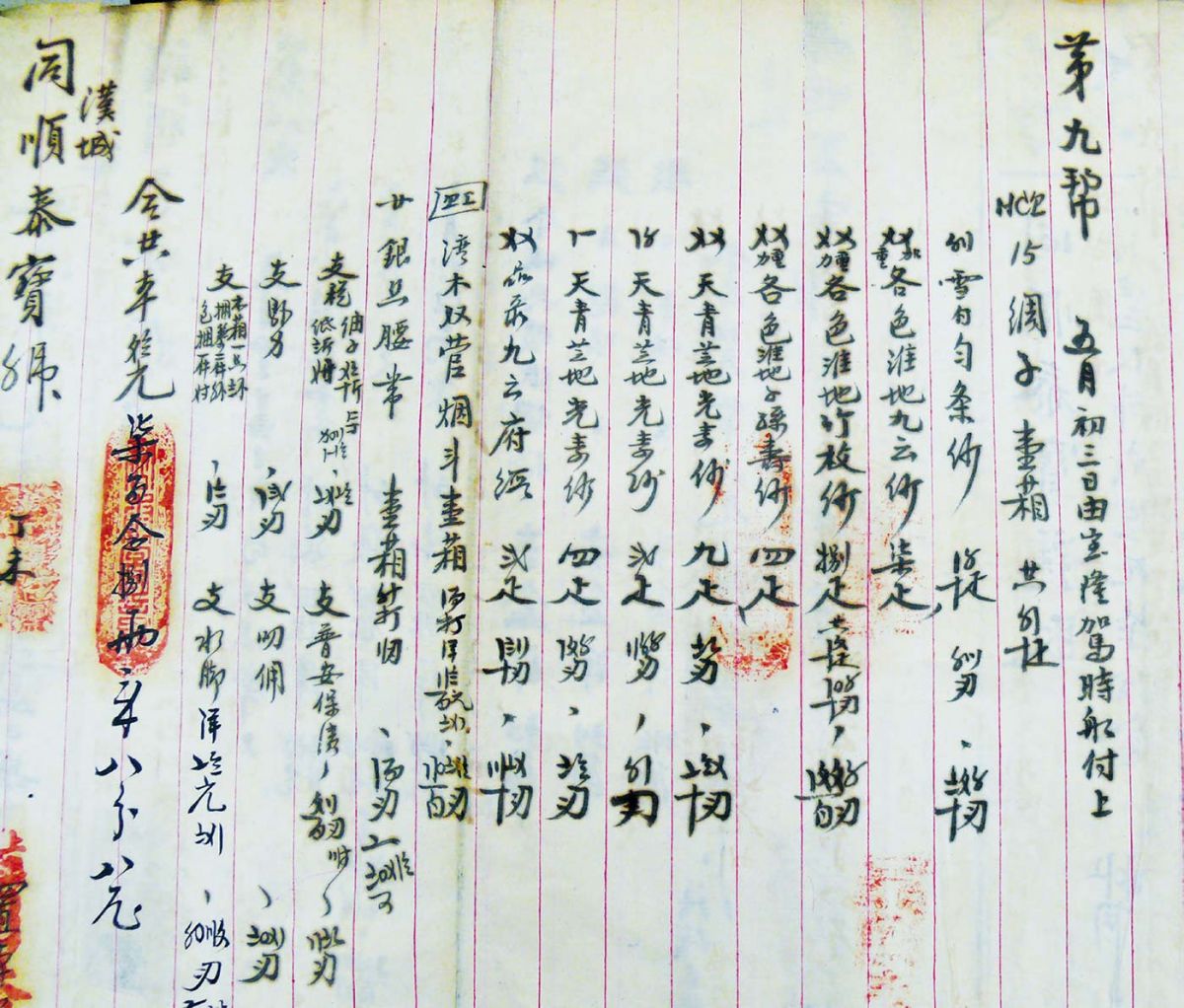

It would occur to very few people that a Chinese name would make it onto the ‘Korean Rich List’ during the Colonial Period of Korea. However, the top taxpayer in Seoul in 1923 was indeed a Chinese person, Tan Jie-sheng (譚傑生, 1953-1929). Tan Jie-sheng was the manager and later proprietor of the Tongshuntai Firm (同順泰號), one of the representative Chinese companies in modern Korea. The Kyujanggak (奎章閣) Archives and the Rare Books & Archival Collections (古文獻資料室) of Seoul National University Library preserve a large amount of the Tongshuntai Firm’s invoices, receipts for transactions and business correspondences. Consisting of seven books (67 volumes in total), those Tonshuntai documents are nearly ready to be published by Guangdong People Publishing House of China.

Although overseas Chinese merchants have always been a crucial agency in Asian trade prior to the 19th century, Joseon Korea was exceptionally isolated from this network unlike Japan and South East Asia. Along with the opening of the treaty ports, Joseon became incorporated into the regional trade system of Asia. Subsequently, Chinese merchants began to settle down around these ports on a large scale following the establishment of ‘Regulations for Maritime and Overland Trade Between Chinese and Korean Subjects’ (otherwise known as the China-Korea Treaty of 1882). While the predominant ratio of the Chinese population in modern Korea was represented by the natives of Shandong Province, the treaty ports at the very first stage of their opening, as well as Seoul at the time, witnessed a diverse composition of Chinese merchants. Those merchants came to Korea encouraged by the possibility of the Korean market and the strong political supports of the Qing government in Korea. Tan Jie-sheng was Cantonese – representing a typical case of a Southerner arriving Korea in this period – and became the richest Chinese merchant up until the 1930s.

The Tongshuntai Firm was founded first in Incheon around 1885 by the Tongtai Firm (同泰號), a Cantonese firm in Shanghai. The owner of Tongtai Firm was Liang Lunqing (梁綸卿) who left the management of the new firm in Korea to the Tan brothers, whose sister married Liang. It was Tan Jie-sheng, who was Liang’s third brother-in-law, that developed Tongshuntai’s business and eventually became its actual owner. Liang Lunqing maintained close relations with the comprador-officers group from Xiangshan County, Guangdong, who had helped Li Hongzhang establish businesses as part of the Self-Strengthening Movement. In addition, there were quite a number of Cantonese returnees from the ‘Chinese Educational Mission’ (留美幼童) program working as Chinese staff of the newly opened Korean Maritime Customs Service or working for Yuan Shikai (袁世凱) as diplomatic officers. The native-place bondage of the Cantonese community both in Shanghai and Korea was an important resource for the Tongshuntai Firm and other Cantonese merchants, which enabled them to secure their initial success in Korea.

At first, Tongshuntai Firm’s growth was based on trade, selling imported British cotton, Chinese silk, and other general merchandise in Joseon and exporting Joseon goods, such as Red Ginseng, gold, and cow hides. Trade mainly took place between Incheon and Shanghai, but expanded to Japan and Hong Kong as well, through Shanghai. Additionally, the close relation with the official group of the Self-Strengthening Movement and their status as the largest Chinese company let the Tongshuntai Firm play a considerable political role in Korea. For example, under the circumstances in which a banking system between Qing China and Joseon was lacking, Tongshuntai was not only responsible for the transfer of government funds between Shanghai and Seoul, but also assumed the role of an official treasury on behalf of the Chinese legation in Seoul. Exploiting this special status, the Tongshuntai Firm could utilize official funds for their cash flow. The money-lending business to Chinese officials and upper class Koreans, including merchants, officials and the royal family, was highly lucrative. One of its debtors was Heungseon Daewongun, father of King Gojeong.

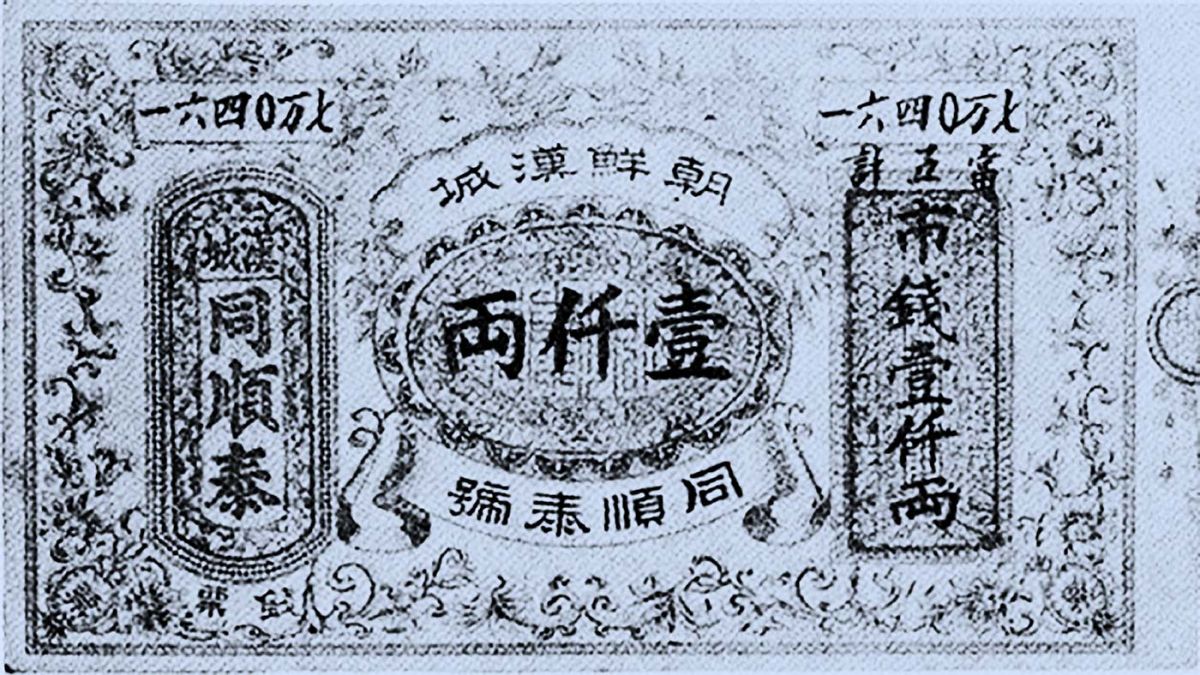

When the Qing government provided the Joseon government with a loan of 200 thousand liang in 1892, Tongshuntai was written down as the lender, due to the anti-Qing sentiment prevalent in Joseon at the time. In return for lending its name, Tongshuntai was granted monopoly of navigation rights along the Han River and the operation of a regular route between Incheon and Mapo. Tongshuntai also issued a note, known as ‘Tongshuntai-piao’ (同順泰票), which was widely circulated in the treaty ports and Seoul as currencies until 1904. During the First Sino-Japanese War, and particularly after the battlefield was shifted into Chinese territory, Tan Jie-sheng monopolized the profit of the wartime boom in Korea and built a big fortune, taking advantage of the temporary setback of the Shandong merchants.

It is worthy to note that Chinese merchants continued to grow in Korea, both in number and in economic power, without the political support of Qing government after the defeat of the First Sino-Japanese War. The trade value with China increased tenfold from 1893 up to 1910 (when the forced Korea-Japan Annexation took place) and grew sevenfold again until 1927. However, as the direct route between Shanghai and Incheon was shutdown following the political withdrawal of Qing, the advantage of the Cantonese merchants, whose strong international trade networks had been based in Shanghai, disappeared; conditions became more favorable for traders from Shandong Province, which was geographically closer. Many Cantonese merchants withdrew as Joseon lost its charm but Tan Jie-sheng chose another path, reducing its dependence on Shanghai by cutting back its trade operations and adopting a localization strategy, which involved branching out into various businesses, such as the sales of Chinese lottery, real-estate development, and managing a taxi service. During this process, the capital of the Shanghai merchants was withdrawn and Tan Jie-sheng became the de facto owner of Tongshuntai.

Real-estate and house leasing business became Tongshuntai’s main means of increasing its wealth during the colonial period. Real-estate investment by Chinese merchants began during the real estate crush caused by the Imo mutiny of 1882 and the Gapsin Coup of 1884, which occurred successively soon after their arrival in Joseon. Because of the massive evacuation of residents from Seoul, the population of Seoul was almost halved and house prices collapsed to 1/4 of their previous value. Taking advantage of this housing market crash, Chinese merchants bought numerous shops and houses located along the main streets of Seoul at an extremely low price. The urban development that subsequently took place during the period of Japanese occupation resulted in the soaring of real-estate prices, which led to the manifold increase in the wealth of the Chinese merchants. Of the Chinese merchants based in Korea, Tan Jie-sheng owned the greatest amount of real-estate; it is said that at one time, Tan Jie-sheng rented out approximately 700 houses in Seoul. The most famous of his properties is where the building housing the Korean National Commission for UNESCO now stands in Myeong-dong.

One reaction to this prosperity of the Chinese merchants was collective anti-Chinese sentiment; criticism of Chinese economic power in Joseon was loudly voiced by both the Japanese authorities and the Korean population. In the 1920s, protective tariffs on Chinese imports increased significantly, while anti-Chinese articles began to frequently appear in Korean newspapers, arguing that Chinese merchants and Chinese laborers were taking wealth and jobs away from the Koreans. The main target of these attacks was Tan Jie-sheng, the richest Chinese person in Korea. Tan Jie-sheng died in 1929. After the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, many of the Chinese in colonial Korea, who had now become ‘enemy aliens’, returned to China. The Tan family of the Tongshuntai Firm also eventually withdrew from Korea and returned to China in September of 1937. This marked not only the end to Tan Jie-sheng’s history of success in Korea, but was also the closing episode to the age of transnational business.

Jin-A Kang, Professor, Department of History, Hanyang University canton@hanyang.ac.k