Pongso no Ta-u, ‘island of humans’ (Lanyu, Orchid Island), is a small volcanic island to the southeast of Taiwan and north of the Batanes Islands (Philippines). Protected for centuries by coral reefs, rumours, and remoteness, at the edge of Chinese and Japanese empires, the Ta-u (also called Yami) have only recently, in the process of becoming modern under Taiwanese rule, been engulfed in the currents of capitalist economies. This Focus section brings together personal stories that reflect how being Ta-u is rapidly changing. Each highlights challenges to the integrity of Ta-u culture, as well as the resilience of Ta-u people.

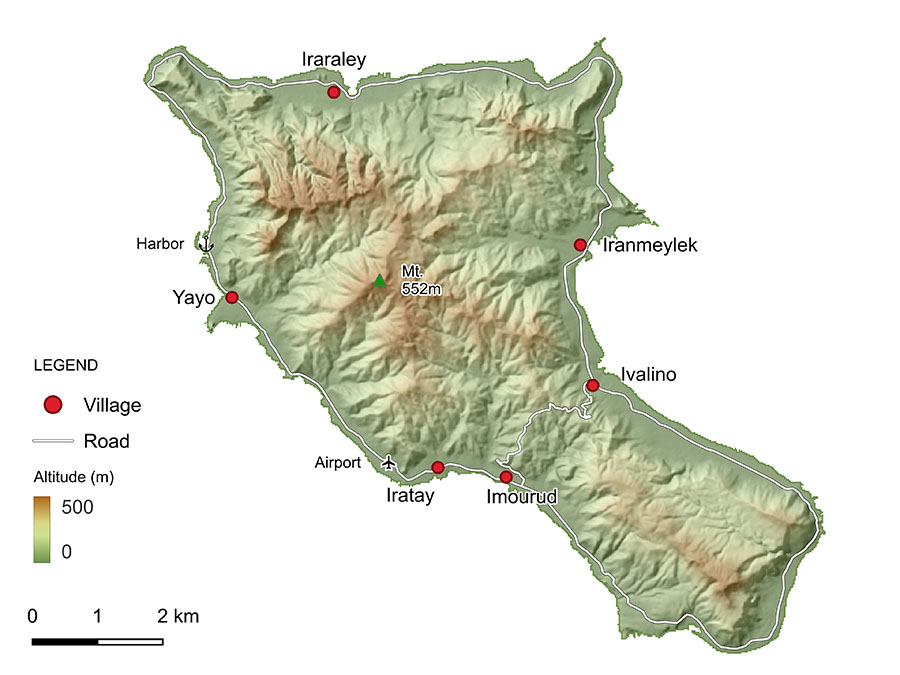

The island of Pongso no Ta-u consists mostly of tropical forested mountains with several peaks over 400 meters, the highest over 500 meters. Six settlements are situated on coastal alluvial plains. For centuries, the Ta-u have wet cultivated taro, the main staple in their diet. Wet cultivation is based on the accumulated landesque capital of previous generations in the form of irrigation channels and walled wet fields, carefully maintained and occasionally expanded. Yams, dry taro, millet, and sweet potato, as well as fruits and vegetables, are grown in small hillside patches. Fish is the main source of protein; pigs, chickens and goats are eaten primarily in connection with rituals and festivities. The Ta-u are widely known for their fishing boats of various sizes. The Ta-u calendar is divided into three seasons: flying fish season, after flying fish season, and before flying fish season. Gathering shellfish along the shore and spear fishing are other common food provisioning practices. The Ta-u may eat over 100 kinds of fish during a year, but the most significant fish is the flying fish, which come in abundance between February and June.

History

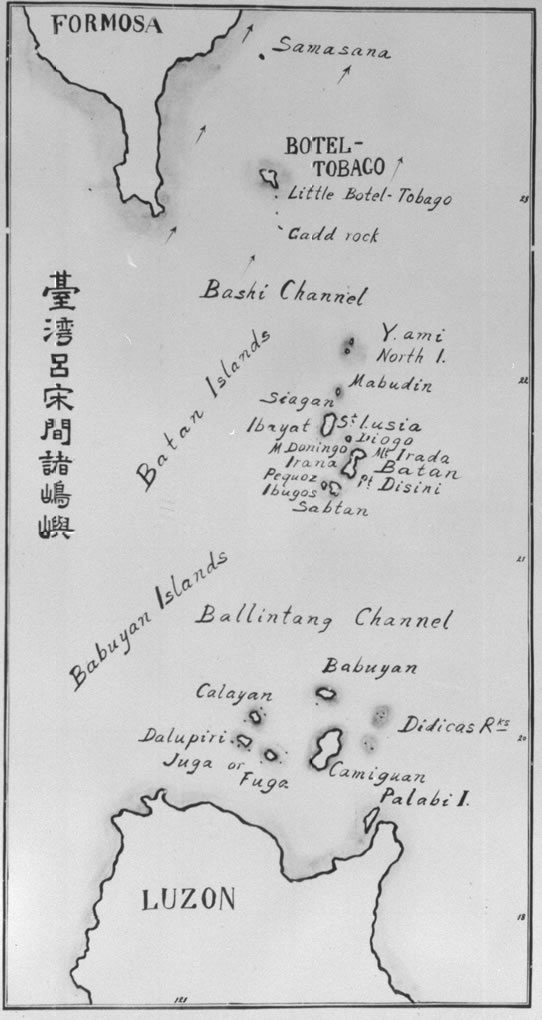

On a clear day, from atop a peak of Pongso no Ta-u, you can see Taiwan to the west and the northernmost islands of the Batanes Archipelago to the south. While the oceanic conditions are challenging, especially crossing the Bashi Channel, we can assume that the early inhabitants of these islands were related and included in each other’s mental maps. Ta-u creation myths, with considerable variations among villages, continue to be told, though with gradually weakening social function. Anthropological and linguistic evidence of their origins consistently paints a picture of roots in and migration from the Batanes Islands. Ta-u is a Batanic language, a subgroup of Malayo-Polynesian languages distinct from all Austronesian languages spoken by Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan. A commonly held understanding is that the Ta-u came to the island from the Batanes Islands, perhaps seven to eight centuries ago. They have since maintained contacts across the Bashi Channel, albeit with considerable hiatuses.

Archeological evidence, on the other hand, suggests human habitation and material flows from Taiwan dating back at least 12 centuries, with more recent analyses indicating settlement as far back as 2500 BP. 1 Recent genetic research shows that the Ta-u have more roots among Indigenous groups in Taiwan than in the Batanes, and that the Ta-u are genetically unusually homogenous, due to long periods of relative isolation associated with ‘bottleneck events.’ It also confirmed oral history that some families are closely related with the Batanes. 2

All in all, with considerable but decreasing degrees of uncertainty, the view of human history on Pongso no Ta-u is one of long periods of isolation, contributing to genetic and cultural homogeneity, with occasional disruptions such as migration from the Batanes Islands resulting in displacement or replacement of language and culture. Traces of prior languages retained in Ta-u support this view. The village communities with which Ta-u kinship groups primarily identify display substantial variation. Isolated over the long run, the Ta-u have developed a wealth of knowledge and practices for living sustainably on their island home.

Under Japanese rule (1895-1945), the island’s first police station was established in 1903, then the first school in 1923, and a second school in 1932. Isolation came to a definitive end when Taiwan and its adjacent islands came under the rule of the Republic of China in 1945. The Ta-u experienced dramatic escalation of colonial activities, including: land dispossessions (1951); establishment of a large prison, primarily for political dissidents (1952-1979), as well as ten ‘veteran farms’ (1958-1991), which together nearly doubled the population; topocide/domicide of traditional villages, replaced with poor quality cement houses (1966-1980); development of exploitative tourism (since 1970s); strip-logging nearly one-third of the island’s forests (1970s); nuclear waste storage, which remains a contested practice (launched in 1973, storage since 1982, new shipments discontinued 1996); and over-fishing near the island during flying fish season (contested in 1990s and 2000s).

Names, transcriptions, and translations

Pongso no Ta-u has historically gone by several names. The Ta-u call it Irala, which means ‘land’ in the sense of navigational direction, where one lands, facing the mountain; or Pongso no Ta-u, island of the people. The two Taiwanese Indigenous groups, the Puyuma and the Ami, call it Botol and Buturu. The Japanese named the island Tabako Shima on a map from 1607. The Chinese named it Hongdou yu (Red Bean Islet) in 1618 and later incorporated it into Hengchun County in 1877. It is said that the peaks of the island reflect a reddish hue at sunset. Subsequently it was most widely known in the West as Botel Tobago. During the Japanese occupation, the island was called Kotosho (Red Head Islet), modifying the Chinese name. And in 1947 it was officially named Lanyu (Orchid Island) by the Republic of China, to celebrate its bounty of moth orchids.

Fig. 2: Map of Pongso no Ta-u.

The Japanese anthropologist Ryūzō Torii, the first of many to study the Ta-u, reportedly asked the islanders the name of their ‘tribe’ in 1897 and was told ‘Yami.’ Although this was possibly a mistake (yami means ‘we’), it stuck well, especially in the anthropological and linguistic literature of the 20th century, but has been disputed by many islanders who associate the name with Japanese rule. The name Yami, however, may not have been a mistake, since it also means ‘north,’ and they were called Yami by their Batanes neighbours to the south. Aware that outsiders referred to them as Yami, they may have meant this in answering Torii’s question. A recent review of ethnographic research on Ta-u ethnonyms confirms that the group historically called themselves Ta-u. Today, roughly a third prefer the name Yami, while a bit over half prefer Ta-u (in various transcriptions). Some who prefer Yami consider Ta-u to be too broad, encompassing all of mankind. Both names occur in the Focus articles. 3

The Ta-u language is primarily oral and has only recently become transcribed in Latin alphabetic form. There are no established ‘correct’ spellings, and transcriptions of the oral language vary both in the literature and among the Ta-u: for instance, Ta-u, Tao, Ta-wu, Dawu, Dao.

Inevitably, problems arise in translating concepts and place names from oral Ta-u into written Chinese characters and finally into written English. Place names in Ta-u describe the place well, including what is appropriate or inappropriate to do there. These meanings get lost and thereby overlooked by Taiwanese tourist agents and tourists, putting their customers and themselves at risk by not understanding the full significance of place names.

One especially important Ta-u concept is ili (‘village’), commonly translated to Chinese as ‘buluo’ (部落), which in English would be translated as ‘tribe.’ Each village name denotes not only a place, but a kinship that maintains its own culture of stories, beliefs, local knowledge, practices, and even architecture, distinct from while overlapping with those of other ili. In our translations of the articles, we use ‘village’ to denote the meaning of ili, allowing the names of villages to denote both the place and the people, kin, who live there.

Fig. 3: Map of Botel Tobago (Orchid Island), 1898, by anthropologist Torii Ryūzō (1870-1953). (Image from digital archive of the University of Tokyo. Public Domain.)

Knowledge and language

In the first essay of this Focus section, Syaman Rapongan – award-winning author of novels and short stories, anti-nuclear waste activist, boat builder, and fisher – takes us to the first encounter with the Island of the Ta-u: the beach. We learn that the beach is more than just a space where land meets ocean. It is a place embodying the spiritual significance of rituals, as well as a “theatre of action” where many of the most vital activities of the Ta-u are performed. With few words, Rapongan poetically conveys images of essential elements of Ta-u knowledge, culture, and relations with the ocean, flying fish, and the island’s ecology. He tells of the salient connections between the mountains, the ocean, and the people, by way of providing timber for the boats, soil, and fresh running water for the taro and other fruits of the forests, as well as a home for the goats and pigs.

Syaman Rapongan equates university disciplines like meteorology, oceanography, and ecology to Ta-u traditional knowledge of the winds, currents, waves, and relationships between land and sea. This knowledge is deeply rooted in how the Ta-u relate with the mountains and the ocean. His essay signals what is to come in the following essays, reverberating insights into fundamental differences between capitalist and Indigenous cultures in their relationships with nature.

Ta-u account for over 80 percent of the island’s population. But the schooling of this population is geared for assimilation into Taiwanese culture and society, through the classroom language of instruction as well as the provisioning of school meals, as emphasised by Syamen Womzas’ article. He enthusiastically develops a complementary curriculum including supplementary school books for teaching elementary school children about various aspects of their natural and cultural milieu. He also works for changing food provisioning at school, including engaging children and their families in planting and harvesting traditional dry cultivated roots.

Knowledge is of great importance to all of the authors. Traditional Ta-u knowledge and loss of knowledge associated with the introduction of new ways of life, economic relations, convenient technologies, relations with nature, and conceptions of the world, are themes that reappear in the essays. Some emphasise the tragic loss of traditional knowledge, others the creative efforts to preserve, adapt, and develop that knowledge. Together they ask us to regard scientific knowledge as one way – among others – of knowing and appreciating the world. The science and knowledge of the Ta-u is also taught, studied, learned, transmitted, and, in its openness to change, enhanced. Stemming from deep relational insights, it is not so much subordinate to as different from dominant academic knowledge.

Traditional Ta-u knowledge is preserved in the Ta-u language and can only be kept alive by being active, in motion. If an activity is discontinued, the experience goes extinct. Extinction of experience involves “the radical loss of the direct contact and hands-on interaction with the surrounding environment that traditionally comes through subsistence and other daily life activities.” 4 Tending taro fields, for instance, requires an abundance of direct contact and hands-on interaction with the surrounding environment, a taste of which we get in Sinan Lamuran’s and Sinan Yongala’s essays. If a field lies fallow, for example, because the woman that tended it works in Taiwan or is otherwise busy in the new tourism economy of the island, her family will have to buy taro from Taiwan for ceremonial festivities. With the fallow field comes loss of the language and the practice of praising taro, an important part of the boat launch ceremony. With discontinued hands-on interaction in the taro field comes loss of immediate contact with the land, which can then more easily turn into an accountable commodity, passing from the practice of commoning to exchange on a market as private property.

Land, state, and capital

The collision between Ta-u and Taiwanese cultures is most glaring in the nexus of land, state, and capital. Ta-u relations with nature, mode of governance, and principles of economic integration could hardly be more opposite to those brought to the island under Taiwanese rule. The Ta-u relate with nature as a sacred whole that they are part of, in the same egalitarian communal way they relate with each other in work, decision-making, and sharing. In Taiwan, capitalist and patriarchic relations determine that nature is valued as resource commodities, while economic integration takes place primarily through markets, backed by a heavy-handed state.

Already in 1951, Taiwan legislated a transfer of Ta-u common land to ‘public land’ and instituted a land registry for ‘private property.’ With the stroke of a pen, and the power to do so, 99.5 percent of the island became ‘public land’ that the state could do with as it saw fit. And that it did.

Fig. 4: Coral reef coast and a boat rowing.

For the Ta-u, “Trees are the children of the mountain; boats are the grandchildren of the sea. All living things in Nature have a soul." 5 When a tree is taken to build boats, Ta-u men sing their praise, respect, and gratitude, and talk with the tree as they cut it down and chip away at the trunk to carve out parts for the boat. In contrast, the Taiwanese state summarily deemed the forest too diverse with predominantly ‘worthless’ species, strip-logged large swaths, and replaced the ‘children of the mountain’ with fast-growing and invasive Australian Pine and White Popinac. Years later, the same state authority reported that the project failed to produce an economically viable forest.

Similarly, Ta-u relate with the soil, the water coming down the mountain, the taro, sweet potato, millet, and other plants they tend in the fields and gardens. These are all spirited beings with whom they live in a relation of sacred interdependence. The Taiwan Veteran Affairs Commission, on the other hand, grabbed over one-fifth of the island’s arable land to establish ten farms (1958-1991) that served as labor camps for about 1000 convicts under the guard of army veterans. Additional Ta-u land was grabbed for building the prison, accommodations, and service buildings. This had severe consequences for the Ta-u, not only in terms of having to buy food to compensate for the loss, but in terms of loss of connections with the land they had become part of, and which had become part of them.

Robin Wall Kimmerer echoes many an Indigenous voice across recent centuries when she observes that “to the settler mind, land was property, real estate, capital, or natural resources. But to our people, it was everything: identity, the connection to our ancestors, the home of our nonhuman kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library, the source of all that sustained us. Our lands were where our responsibility to the world was enacted, sacred ground.” 6

Land, tourism, and waste

The Ta-u have complex land rights customs spanning ocean, beach, settlement and forest, a dozen specific land uses, and five ownership types. 7 Until recently, none of these involved money when land was transferred between users, be they individuals, families or communities. But the invasive species of money has for decades been seeping into Ta-u life as Taiwanese capital scrutinises the landscape for ‘investment opportunities,’ opening up channels for extraction of value wherever land is ‘under-utilised’ and potential land rents and returns on investment can be found. Several authors mention the way conforming to money – letting go of alternative relations deeply embedded in Ta-u culture – has become a necessity. Nowhere has this been channeled so effectively, with such profound impact, as in the tourism industry, now the primary source of revenues in the local economy.

Syaman Lamuran gives a concise overview of the development of tourism on Pongso no Ta-u since the late 1960s. Slowly, the Ta-u villages have managed to turn the tide and gain control over the characteristics of tourism, including ownership and management, qualities of activities, and educating tourists in ways that enhance the experience, for tourists and for the Ta-u people. But there remain problems and issues. In several villages there are instances of Taiwanese getting Ta-u people to sign lease contracts on land for investing in various tourism businesses. Because the land is not privately owned by individuals and is not on any market, these have been the source of much tension and suffering in some families and communities, who should have been party to the decision. Some contracts are disadvantageous for the Ta-u by covering many years without any clause on renewal and adjustment of lease fee. The most publicised case, the Mori incident, concerned a lease with the local government for establishing a cement factory. 8

Another major concern with the flourishing of tourism, highlighted by Syaman Lamuran, is the issue of waste, as tourism accounts for massive volumes of material flows to the island. Sinan Hana writes that the beach is like a furniture store, where you can find useful things like a table. Everything has its use. In one of the Ta-u origin myths, as retold in a children’s book, “the bamboo man and the stone man gave all the people their most solemn advice, ‘no matter what you do, do not waste anything. Use only those resources that you need and do not spoil anything that the creator has given to us.’” 9

Fig. 5: Vanuwa. The beach where

elders gather and share knowledge

with the young.

The problem now is that the volume of waste flooding the island is more than the Ta-u can feasibly make use of, as evident in the growing garbage disposal site south of Imourud. In just the month of June 2019, tourism left 1284 tons of garbage on the island. It is transported to Taitung and from there to Kaohsiung. 10 To understand the proportions: this small island with roughly 5000 residents received over 150,000 tourists per year in 2022 and 2023, peaking at about 30,000 in the month of June. 11 Lack of sewage treatment infrastructure combined with rapid increase in sewage volume and chemical pollutants is a ticking bomb. Sinan Lamuran explains that it is no longer advisable to cultivate land below the level of settlements.

Navigating a future

The contributions in this special section convey Ta-u determination and resilience. Si Rapongan follows in the footsteps of Syaman Rapongan in maintaining the Ta-u boat building and fishing culture. Syamen Womzas, Sinan Lamuran, and Sinan Yongala express determination to steward Ta-u food culture into the future. Sinan Hana creatively develops Ta-u architecture and inspires others to follow suit. Syaman Lamuran navigates the Ta-u path towards sustainable small-scale island tourism, benevolently soft towards Ta-u nature and culture. They represent many other Ta-u people struggling to be Ta-u and modern. In September 2024, a 20-person, 12-meter-long boat built of 22 pieces of different tree species will be rowed to the Batanes Islands, reports Si Maraos, director of Indigenous Peoples Cultural Foundation – one of many efforts to keep Ta-u culture alive and flourishing. 12

Annika Pissin is lecturer and researcher at Lund University. As an anthropologist and historian her earlier work focused on childhood and girlhood in China, and now revolves around food and gardening. She is currently establishing a small forest garden in southeast Sweden. Email: annika.pissin@keg.lu.se

Huei-Min Tsai is professor emeritus at the Graduate Institute of Sustainability Management and Environmental Education and adjunct professor at the Center for Indigenous Research and Development, National Taiwan Normal University. Her research interests include island geography, small island studies, Indigenous knowledge systems, social-ecological systems, environmental history, and sustainability science. Email: hmtsai@ntnu.edu.tw

Eric Clark is professor emeritus at Lund University. His research interests include political economy, political ecology, island development, sustainability and degrowth, gentrification, financialisation, and critical agrarian and food studies. He is currently a novice in the art of beekeeping. Email: eric.clark@keg.lu.se