South Korea: the corruption that built its economy

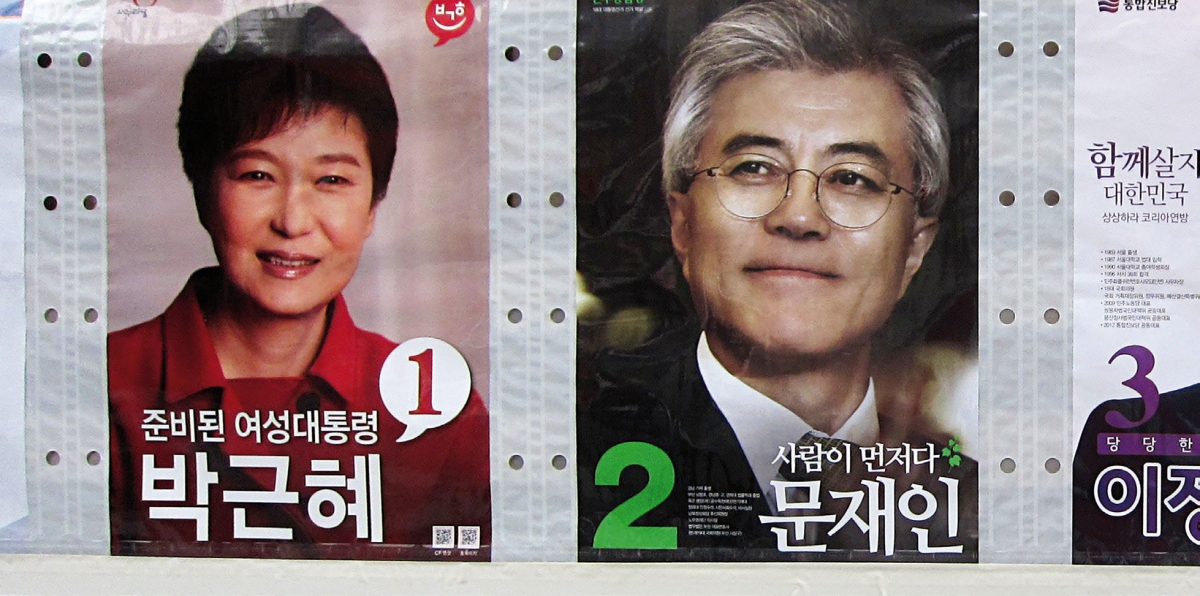

On May 9, democracy triumphed in South Korea, as the country elected a new leader – the Democratic Party candidate Moon Jae-in. Back in March, the country’s Constitutional Court had removed President Park Geun-hye on charges of corruption. This momentous decision came after an independent investigation last year alleged Park had used her office to enrich a childhood friend and solicit donations from major companies in exchange for favors.

The scope of these allegations and the magnitude of their consequences brought into focus South Korea’s complicated relationship with corruption. This latest instance of government malfeasance thrust the country into some turmoil, but corruption has not always been so detrimental to Korea. In fact, if not for the economic benefits of corruption, South Korea would not be the industrialized nation it is today.

In most places in the world, corruption tends to be growth-reducing, but this is much less true in East and Southeast Asia, where it tends to be growth-enhancing. In the 1960s, President Park Chung-hee (father of the recently deposed president) struck deals with a small number of Korean capitalists, which worked as follows: The Park government provided these capitalists promotional privileges—particularly cheap credit from state-owned banks and monopoly privileges in local markets—to grow their firms. Promoted firms were expected to meet government-mandated export targets. If the capitalists met export targets, they got more privileges. If they did not, they lost, or were threatened with the loss of, those privileges. In exchange, promoted firms kicked back a share of their profits to Park and his political entourage. Park and his government cronies used the kickbacks to finance election campaigns, buy off supporters and enrich themselves.

In this model, corruption was growth-enhancing. One of the side effects of this corruption-and-growth model in Korea was the rise and emergence of the chaebols (family-owned mega-conglomerates), such as Samsung, Lucky-Goldstar, and Daewoo.

Not surprisingly, this corruption and growth model has spread to Southeast Asia (especially Indonesia and Thailand, but also Malaysia, to a lesser degree). Governments in Southeast Asia developed very clear and similar corrupt relationships with a small number of what became large conglomerated firms, especially Indonesia's cukong entrepreneurs (Sino-Indonesian capitalists favored by General Suharto) and what became large Sino-Thai conglomerates in Thailand. Just as in Korea, Southeast Asian governments used kickbacks from favored businesses to shore up their political support and enrich themselves.

There are, of course, major drawbacks to this model. For one it undermines political legitimacy. In Indonesia, public revulsion over corruption helped topple Suharto from power. Over time, it can lead to changes in the relationship between government and business; while government was initially the senior partner in this corrupt relationship, businesses gradually gained power by competing for seats in parliament and pulling the levers of economic policy, pushing corruption into a growth-reducing direction.

Park Geun-hye’s ouster represents a clear victory for transparent governance and the rule of law in South Korea. The transfer of power to Park’s left-wing opposition is an understandable popular reaction to the latest incidence of corruption, and was not unexpected.

But history tells us that illicit ties between Korean businesses and Korean governments run deep. It remains to be seen whether the Korean political and economic establishment can move on from the wide-reaching scandal that brought Park down. The world should follow the next developments with a wary eye.

Michael Rock is the Samuel and Etta Wexler Professor of Economic History at Bryn Mawr College. His most recent book is Dictators, Democrats and Development in Southeast Asia (Oxford University Press, 2016). He is currently working on a book tentatively titled Democracy, Development and Islam.