Sharing the art of the brush

As part of the ICAS 11 Cultural Programme, two calligraphy workshops took place in the IIAS building at Rapenburg 59. Based on the enthusiastic reactions of the participants, they turned out to be a great success, not in the least thanks to their inspired and skilled instructor, Cara Yuan.

Cara had designed the workshop in such a way that it was both a cultural journey and the opportunity to experience the subtle working of the brush itself. It was limited to a maximum of 15 participants per workshop because Cara wanted to be able to give her attention to all the participants while they were trying out the brush themselves. Before the participants set to work, Cara introduced the Four Treasures of Chinese Calligraphy (brush, ink, inkstone and paper), while touching upon its long history and lasting significance and role in contemporary Chinese society.

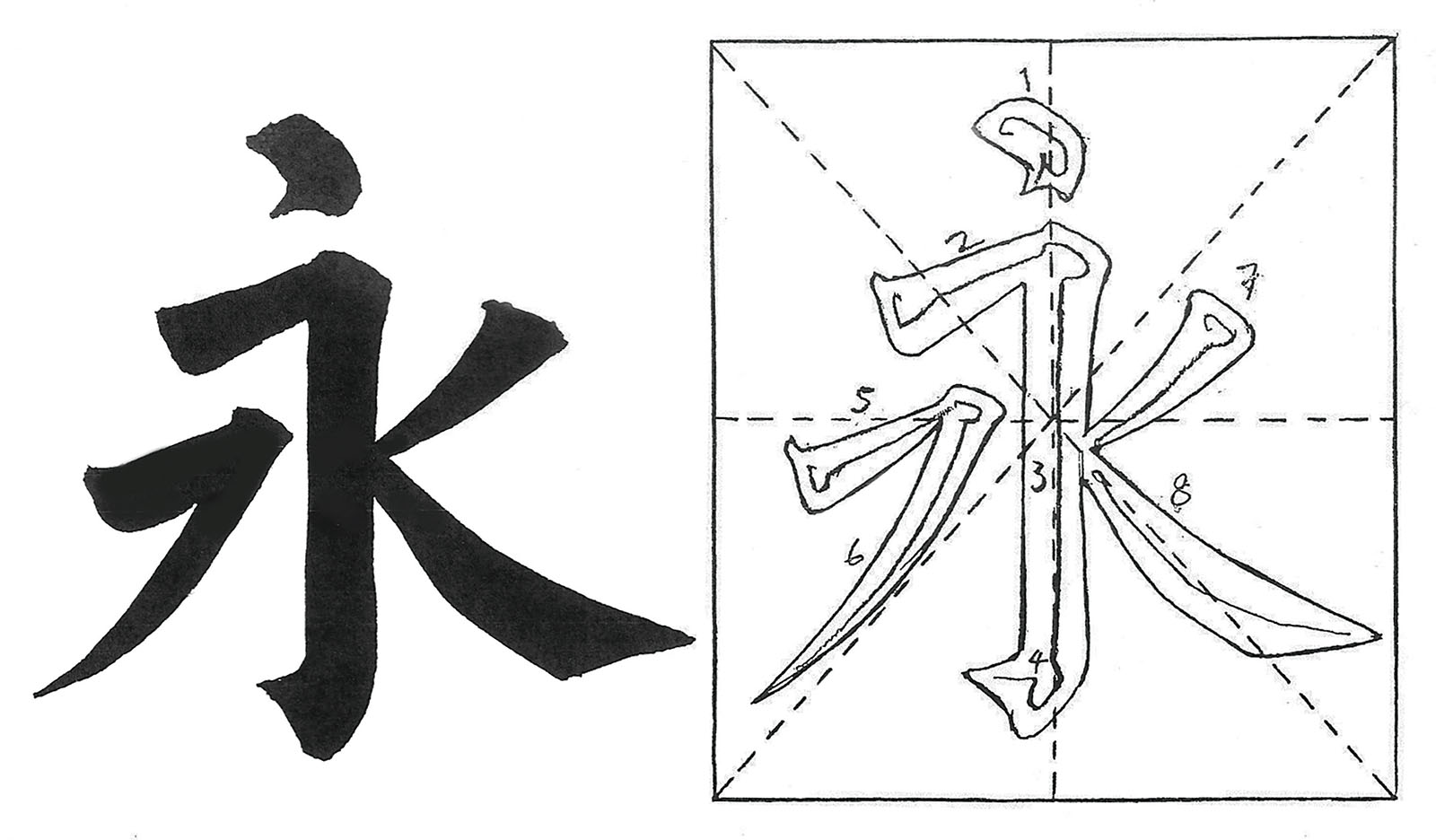

A Chinese brush, made of different types of animal hair, is round and pointy and has a very different effect than a western paintbrush. Moreover, it should always be held vertically, in a 90-degree angle with the surface of the paper. When you see Cara at work, explaining calmly and clearly what she is doing, it all seems very doable, but when you try it yourself, it's not that easy. It requires not only a steady hand, which is difficult enough, but also an insight into and a grip on the subtle interaction between brush, ink and paper, whereby the outcome is directly influenced by applied pressure, inclination, speed, and direction. When drawing a line, which may be straight, curved, have a round or straight bend, and may end with a hook, the brush must be lifted and placed back in the right place, without it ever coming off the paper. To put beauty in a stroke, it is thicker and thinner, darker and lighter, in different places, which can be accomplished by variations in the energy exerted. The right shape may be achieved by distributing the pressure unevenly over the brush, with just a little more pressure on one side than the other. Cara had the participants practice with the character 'yong' (eternity), which demonstrates the eight fundamental strokes.

Worksheet used in the workshop of the character ‘yong’ (eternity), demonstrating the eight fundamental strokes.

The ink consists of soot and a binder (glue) and comes in ink sticks, which are rubbed with water on an inkstone until the calligrapher is satisfied with the consistency of the liquid ink. The inkstone itself contains no ink. They come in many shapes, sometimes beautifully decorated, and typically have a flat part to rub the ink on and a reservoir for the liquid ink. The quality of the ink, how much ink the calligrapher allows the brush to absorb, and how much he lets flow on the paper all affect the result.

The type of paper also has a significant impact. Rice paper, for example, absorbs the ink much more strongly than ordinary drawing paper, which has a strong effect on the interaction between brush and paper. Other objects used include paperweights to hold down the paper, brush rests, and brush washers (used to dilute the ink on the brush if it gets too thick), and water droppers to gently add water when grinding the ink stick on the inkstone.

Not surprisingly, as Cara explained, Chinese calligraphy is regarded as one of the highest forms of art in China. A good piece of calligraphy, most importantly, conveys emotion; the state of mind of the calligrapher is crucial, the result personal and unique. After the workshop, Cara told me the story of the ‘Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion’ (or Lanting Xu) by Wang Xizhi (303-361), who is regarded as the greatest calligrapher in Chinese history. In 353, Wang invited a large group of literary friends to his Orchid Pavilion. They sat down alongside a stream and held a drinking contest. Wine was sent floating down the stream and the nearest person to where it stopped had to compose a poem, or drink three cups of wine. By the end of the day, they had produced 37 poem and Wang wrote his famous Preface on the spot. Because the text contained some errors, he decided to rewrite it a few days later, but no matter how hard he tried, he was unable to capture the atmosphere from that day by the stream, in his handwriting. Dissatisfied with his new work, he decided to stick with the original text. Cherished as a masterpiece, it was handed down for generations, and many copies were made by other calligraphers. The original is now lost; legend has it that it eventually came into the hands of Emperor Tang Taizong (598-649) of the Tang Dynasty, who admired Wang's work so much that it was buried with the Emperor in his mausoleum. Today, only copies remain, errors and all.

The participants at work in the IIAS conference room.

Chinese calligraphy is not just something from the classical past, but a living art form, practised by many, and not just in the 'scholar's studio'. To illustrate this, Cara showed a photo of people working on a piece of calligraphy, using a huge brush and water, on the tiles of a park in Beijing.

Participants

The participants had different motives for joining the workshop. Most of them already had some experience and wished to learn more, for example, about the difference between Japanese and Chinese calligraphy. For others, it was a new experience, as it was for our very own Newsletter designer, Paul Oram, who also attended the workshop. With his affinity and love for graphic design, he didn't have to think twice when he saw that this workshop was being offered. In the space of just two hours, it was, of course, impossible to do full justice to all aspects of Chinese calligraphy, let alone the enormous history and culture that goes along with it. However, based on the feedback I received, I can safely conclude that the introduction was widely appreciated, and indeed a great success.

Cara explains the strokes of the character ‘yong’ to the participants.

This workshop was a highlight for me during my week at Leiden, and I feel truly blessed to have had this opportunity. Thank you so much Cara for that wonderful teaching, of the skill, and its philosophy, all within the span of an hour! The way that the workshop was organised, with all the authentic material, the brushes, the ink sticks and ink stones, and Cara shared with us her very special ink stone which was a gift from her father.....it all added to us appreciating how it is an art in itself, with so much of tradition, skill and philosophy in it. From the carefully thought out strokes for beginners' practice to the character that we learnt, ‘eternity’, it felt very surreal, and resonated at a deep level.

– Sonali Mishra, University of Delhi.

Cara Yuan

Cara Yuan (www.carayuan.nl) is a professional artist, photographer and calligraphy teacher. She was born and raised in China. Her father is an artist, specialised in Chinese painting, her grandfather a Chinese calligrapher. She started Chinese calligraphy at a very young age, exhibiting her work in China and Japan before her 20th birthday. In 1998, Cara moved to the Netherlands to study at the Amsterdam University of the Arts to become a teacher. Cara’s work as an artist (Chinese water-based ink techniques, abstract painting and photography) is characterised by a mix of Eastern and Western influences.

Sandra Dehue, IIAS content editor and editor of the network pages in The Newsletter s.a.dehue@iias.nl