Shaping a Nation in Stone: Rizal and the Monuments of the Philippines’ American Colonial Era

The Philippine built environment has played a crucial role in shaping the legacy of José Rizal (1861-1896), the national hero. This is especially apparent when examining the history of American colonization in the Philippine Islands (1898-1946). Rizal’s writings and execution by the Spanish not only catalyzed the Philippine Revolution but transformed him into a powerful nationalist symbol. To harness his popularity, U.S. colonial authorities erected Rizal monuments throughout the Philippine Archipelago, thereby portraying him as a model of cultural assimilation. However, many Filipinos during the early 1900s viewed the statues as symbols of resistance against foreign rule. The tension of how monuments were seen and used, to be brief, exposed how they were ‘active participants’ in contests regarding the evolution of Filipino national identity and consciousness. The Rizal monuments built during the early 1900s also reveal how the Philippine cityscape became a battleground for agencies seeking to shape and inform what ‘being Filipino’ entailed.

When the United States assumed control of the Philippine Islands following the Spanish-American War of 1898, one of the new colonial administration’s first priorities was to establish, literally and figuratively, a ‘visible presence.’ During the following decades, the Philippines saw the emergence of monuments and statues honoring pambansang bayani (national heroes) – like José Rizal – so as to represent and celebrate Filipino nationhood. 1

The concept of national heroes was especially apparent during the late 19th and early 20th centuries; it was an era marked by the Philippines’ struggle for independence from Spanish colonial rule. Thus, as Filipinos sought to define their identity and assert independence, the need for heroic figures to inspire and bring the people together became evident. These heroes were to embody the ideals, virtues, and aspirations of ‘being Filipino,’ thereby serving as symbols of resistance, valor, and patriotism.

Indeed, after 1898 and the change in colonial regimes, monuments were employed not as mere decorative flourishes within Philippine built fabrics. Rather, they were purposefully constructed as tools for the American regime to project its power, to shape the Philippine national consciousness, and to set its legacy in the islands over which it now had political control. Yet, as this article explains, Rizal monuments took on numerous functions in the context of American colonization.

The first monuments erected

After 1898, the construction of public monuments and the beautification of urban plazas emerged as a key strategy for the colonial government to shape national identity and civic consciousness. At the forefront of this effort was the strategy to erect Rizal monuments. Consequently, in lauding the Filipino national hero, statues and monuments became a central feature of town squares and public parks across the archipelago. 2

The drive for monument building and plaza beautification was shaped by multiple factors. One key motivation was the need to commemorate significant historical events, individuals, or milestones of cultural and national importance (as defined by the Americans). 3 The creation of beautified plazas also provided sites for civic activities and gatherings, often featuring bandstands that offered platforms for public performances and cultural events. In fact, these spaces became focal points for community engagement and civic participation, facilitating social interactions and fostering a sense of unity. 4

Plazas – or ‘People’s Parks,’ as they became known – served as gathering places for communities given that they provided open areas for local social, cultural, and political activities [Fig. 1]. Commonly, these endeavours were often supported by civic organizations, municipal governments, and private donors, who collaborated to fund and construct more monuments, parks, and other public spaces. From the American perspective, the erection of additional monuments and the laying out of more public spaces signaled the advancement of civilization.

The origins of Rizal monuments can be traced back to the early 20th century, when the American colonial government sought to erect a grand memorial to commemorate the life and legacy of Dr. José Rizal. Rizal, the renowned writer, physician, and revolutionary, had been executed by the Spanish colonial authorities in 1896 in Manila, allegedly for his role in inspiring the Philippine independence movement of that year. His death, and subsequently the perception of his martyrdom, transformed him into a powerful symbol of Filipino nationalism thereby making him an ‘ideal figure’ for the Americans to promote as they sought to cultivate a new national identity among their colonial subjects.

The Rizal monument in Daet, Camarines Norte, erected on December 30, 1898, was the first such memorial erected and remains the oldest surviving one in the Philippines. In Manila, the capital city, one of the first monuments venerating the Filipino national hero was erected in 1910. This Rizal monument stands at the corner of Rizal Avenue and Alvarez Street in San Lazaro Park.

Financed through proceeds from the annual Philippine Carnival, 5 a colonial-era public festival, this monument honored the Filipino hero and became a prominent landmark in the city before it was transferred to San Lazaro Park. However, the city’s first grand Rizal monument was dedicated in 1913 in Manila’s downtown Luneta Park – today known as Rizal Park, 6 a large-sized public space that had been redesigned following the American architect-planner Daniel Burnham’s recommendation in 1905 to remodel the layout and appearance of the Philippine capital city [Fig. 2]. Standing tall at the centre of the foremost green space in Manila’s inner districts, the monument depicted Rizal in a heroic pose, with one hand resting on a book and the other gesturing defiantly.

Fig. 2: Luneta Park in present-day Manila has long been a significant public space, dating back to the Spanish colonial era when it served as an execution ground. The strategic placement of the Rizal Monument at the centre of this historic park symbolizes the enduring legacy of the Filipino national hero, whose martyrdom fuelled the struggle for independence. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user PhiliptheNumber1 and reprinted under a Creative Commons License, 2024)

The choice of location was strategic, as Luneta Park had long served as a gathering place for the people of Manila; it has a history of being used to host civic events, cultural performances, and political rallies, for instance. By situating the Rizal Monument at the heart of this public space, the colonial authorities sought to embed the image of the national hero into every aspect of Filipino civic life.

The highly-visible monument was to serve as a focal point for the Filipino people, who would visit Luneta Park to commemorate the anniversary of Rizal’s birth and death, to pay tribute to his memory, and to reaffirm their sense of national identity. However, in light of the design of the monument by Richard Kissling, Rizal’s role in the Philippine Revolution against Spain was largely downplayed; the monument’s form and engravings instead emphasized his execution by the Spanish authorities – a narrative that served to position the United States as the Philippines’ liberator from Spanish colonial oppression.

The Rizal Monument phenomenon

The development of public spaces played a crucial role in the placement and visibility of colonial-era monuments like the Rizal Monument of downtown Manila. Act 3482 7 (1928) assigned the Director of the Bureau of Public Works (BPW) the task of creating overarching urban plans for the upkeep and future growth of provincial towns and cities. These urban development designs ensured that public places, infrastructure, and architectural features were all aesthetically integrated. The strategic location of the Rizal Monument in Manila’s prominent Luneta Park was no exception, with this iconic statue of the Filipino national hero standing at the centre of the carefully redesigned and landscaped public space.

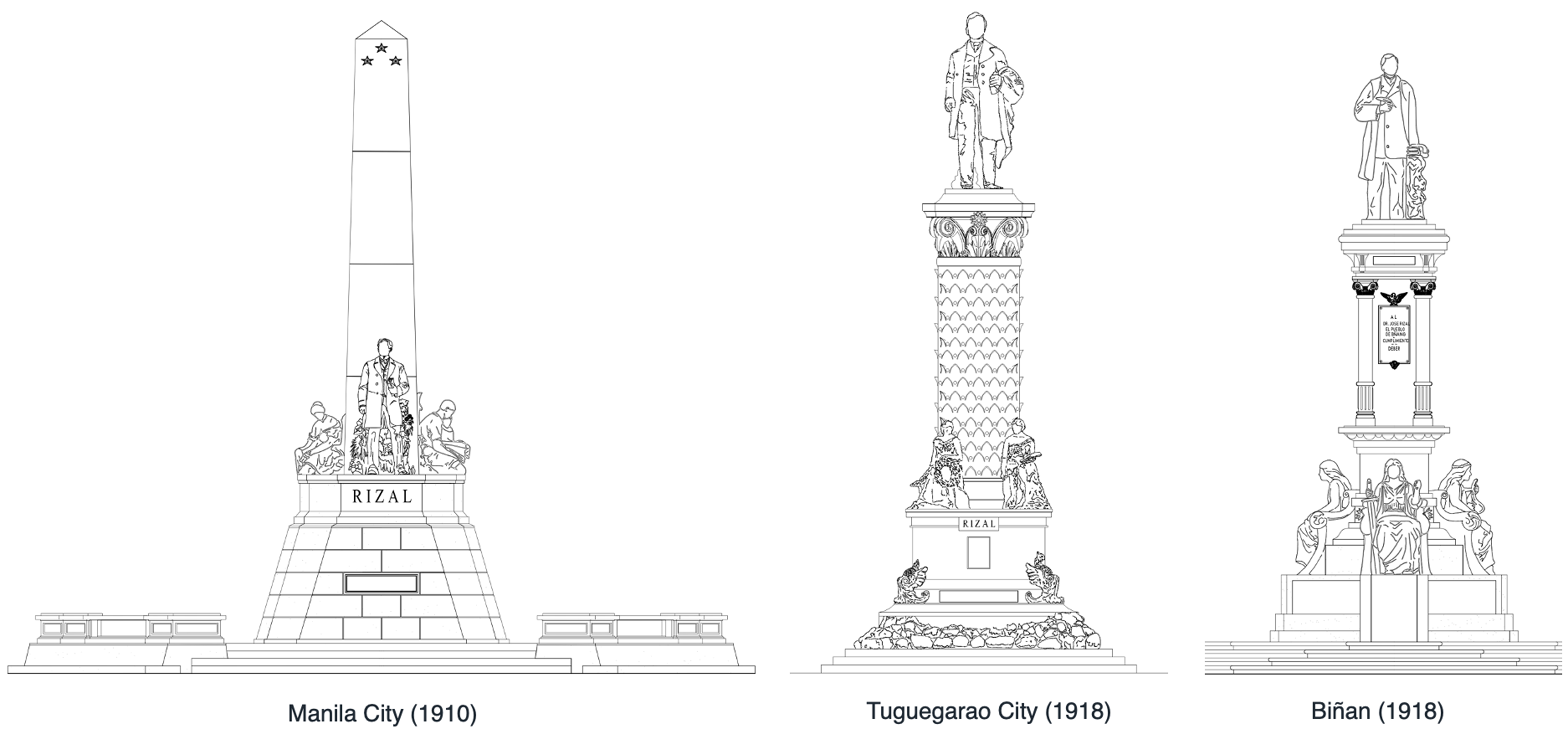

The influence of the Rizal Monument extended far beyond the capital; replicas and adaptations of the iconic statue began to appear in town plazas, public parks, and school campuses across the Philippine archipelago. These monuments became a prominent feature of the colonial landscape, serving as visual reminders of Rizal’s centrality to the project of Filipino nationhood [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3: The iconic Rizal Monument in Manila’s Luneta Park inspired the proliferation of similar statues honouring the Filipino national hero across the archipelago during the early 20th century. These monuments, erected in town squares, public gardens, and school grounds, reflected the architectural styles and ornamentation prominent during the 1910s, and showcased the regional diversity of Philippine commemorative art as well as the enduring legacy of José Rizal. (Photo by the author, 2024)

The widespread presence of the Rizal Monument was consequently not arbitrary; the American colonial regime recognized the power of “public art and architecture to shape the attitudes and behaviors” of the Filipino populace. 8 By populating the colonial landscape with images of Rizal, the authorities sought to mold the Filipino citizenry in the image of their national hero – instilling values of learning, self-improvement, and civic engagement. 9 Of significance, too, these monuments still stand and still inform the populous today in the postcolonial setting as to their identity as ‘Filipinos.’

To bolster Rizal’s importance, events in his life as well as his writings were carefully curated and promoted by the colonial authorities as exemplars of the ideal Filipino citizen. For example, his commitment to education, his advocacy for social reform, and his non-violent approach to the independence struggle were all held up by the Americans as virtues to be emulated by the Filipino people.

The Rizal Monument, in Manila and subsequently elsewhere, became a physical embodiment of social ideals, thereby serving as a constant visual prompt for Filipinos – irrespective of gender, age, wealth, and social class – to cultivate the same qualities of character and civic-mindedness.

At the same time, the construction of Rizal monuments also provided a “limited outlet” for the expression of Filipino identity and agency within the colonial system. While the American authorities maintained tight control over the broader monument-building program, in allowing for the celebration of Rizal as a Filipino national figure, it permitted Rizal monuments to become hubs for Filipino people to enact their grasp of Filipino civic identity. In other words, whilst the colonial authorities sought to harness monuments of Rizal for their own nation-building agenda, in Filipino eyes, as time unfolded, such architectural features acquired new meanings with regard to national consciousness and nationhood – meanings determined by themselves, not the Americans.

Rizal monuments stand as complex symbols of the American colonial experience in the Philippines. On the one hand, these architectural objects were tools employed by the American regime to shape Filipino citizens in the image of their national hero, inculcating values such as self-learning, self-improvement, and civic engagement. Yet on the other hand, monuments came to serve as rallying points for the expression of Filipino nationalism, in so doing providing platforms for the celebration of local identity and the cultivation of a shared sense of national consciousness. In this way, the Rizal Monument in Manila, as a case in point, highlights the inherent tensions and contradictions of the American colonial project in the Philippine Islands. So, while the Americans sought to exert control over the Filipino populace, they were ultimately unable to fully suppress the deep-rooted nationalist sentiments that found expression through the veneration of Rizal and the reclamation of public spaces for the performance of a distinctly Filipino civic identity.

Monumental legacy: Monuments as symbols of (national) Filipino identity

The evolution of monument building in the American colonial Philippines reflects the broader arc of the colonial experience itself. From the initial efforts to solidify American power, to the gradual recognition of Philippine nationalism, to the ultimate transition to independence, the shifting landscape of seeing, reading, and using monuments serves as a tangible embodiment of the political, social, and cultural transformations that the country underwent during the 1900s prior to the onset of World War II in 1941.

Through the careful curation of public space and via the formation of collective memory, the American colonial authorities intended to (re)shape the very foundations of Philippine national identity. Yet, as the monuments built during the early 1900s testify, this was a project fraught with tension and contestation, i.e. a constant negotiation between the colonizer and the colonized.

The legacy of the Rizal Monument in Rizal Park, Manila, and those erected in other towns and cities throughout the country, continues to resonate in the Philippines today. The monuments stand and serve as potent symbols of the country’s complex colonial past and the ongoing struggle to define the contours of what Filipino nationhood is, and is not.

As the nation grapples with the aftereffects of its colonial experiences, Rizal monuments in plazas and other public spaces stand as a testament to the power of public art and architecture to shape the collective consciousness of a people – and to the enduring capacity of that consciousness to assert itself, even in the face of the most formidable colonial impositions in the postcolonial setting.

As the Philippines looks back on this complex historical legacy, the monuments that dot its cityscapes continue to hold profound significance. They stand as lasting reminders of the nation’s struggle for self-determination, as well as the enduring influence of its colonial past held by Spain and the United States. In studying the country’s silent stone sentinels, it is possible to gain a deeper understanding of how the built and designed environment can become a battleground for the shaping of national consciousness. Moreover, it reveals that any such battle can never truly be won. Rather, it is perpetually reenacted through the artistic objects that seek to define a nation’s public spaces.

Claudia Isabelle Montero is presently completing her PhD study in the Department of History at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, where she previously completed her MPhil degree. Her ongoing research project investigates the intricate dynamics surrounding monuments and civic spaces in the Philippines, with a particular focus on their relationship within the context of American colonial urbanism. Email: claudia.montero@cuhk.link.edu.hk