The Robert Hart Photographic Collection at Queen's University Belfast

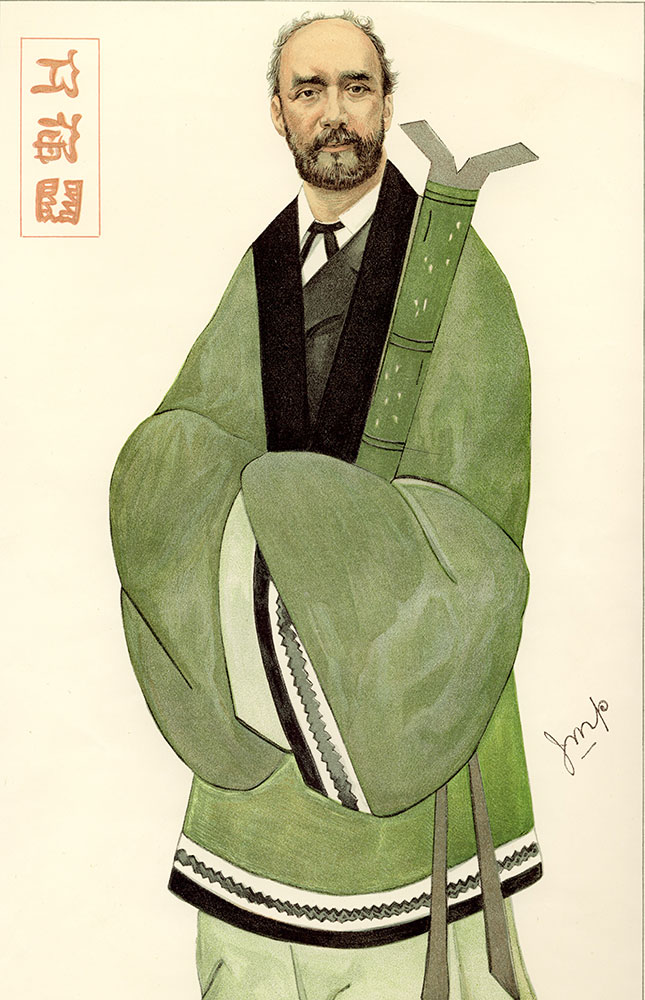

Sir Robert Hart, the Irish-born Inspector-General of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs between 1863 and 1908, exerted such wide-ranging influence that the historian John Fairbank called him one-third of the “trinity in power” in China in the later nineteenth century.1 Historians have long recognised the importance of Hart’s personal archive, particularly his diary in seventy-seven volumes held at Queen’s University Belfast, for understanding Sino-Western relations in the late Qing period.2 Yet Hart’s collection of several thousand photographs, many of them unique, has not received the same degree of attention. A preliminary selection of these photographs has been published as China’s Imperial Eye, and the full collection is now being digitised.3 Hart’s photographic collection shows us not only something of the look of late Qing China, but also helps to reveal how this controversial figure viewed the country he served for forty-nine years.

Sir Robert Hart: the ‘insignificant Irishman’

In a generally indulgent biography, Hart’s niece Juliet Bredon stated that her uncle was once described as “a small, insignificant Irishman”.4 Few of his contemporaries would have recognised that description, however. Sir Robert Hart (1835-1911) was probably the most influential European in late Qing China. His career coincided with the final years of the Chinese empire, ending shortly before the Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911, the year of Hart’s death. By 1900, the customs service over which Hart presided had a staff of almost twenty thousand and raised the bulk of Qing imperial revenue. Several of Hart’s projects transformed China’s infrastructure, from the postal service to lighthouses, and he also helped to shape foreign relations during the Qing’s last half-century, through close relationships with senior officials of the Chinese government in the Grand Council and in the Zongli Yamen (the Qing court’s Foreign Ministry), and with foreign diplomats alike.

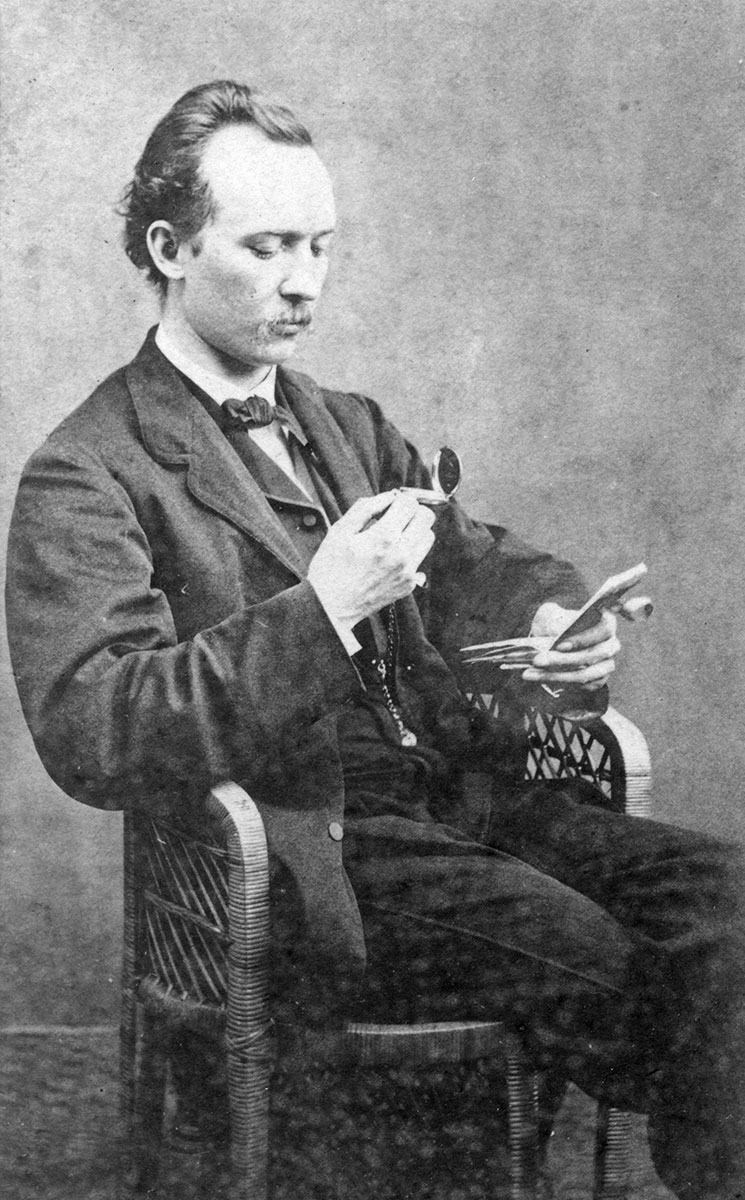

Born in Portadown in County Armagh, Ireland, Hart was a brilliant student. He graduated in 1853, aged only eighteen, from what was then the Queen’s College, Belfast (now Queen’s University Belfast) and continued to graduate studies. The following year, however, Hart abandoned his research when he won a hotly contested position as a trainee interpreter with the British consular service in China. He was attracted both by the generous annual pay of £200 and by the chance to leave Belfast, where - hardly uniquely among students - Hart had acquired a taste for nightlife and sexual encounters. After a brief stay in Hong Kong, the British consular service sent Hart first to Ningbo and then to Guangzhou, where Hart’s unusual facility for languages became rapidly apparent.

In 1859, Hart made the second abrupt career change of his young life when he resigned his British diplomatic post in order to join the new Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs. Though an agency of the Chinese government, the purpose of the Maritime Customs was to tax the foreign trade which Britain and other powers had compelled China to permit. The first foreign-administered customs was established in Shanghai in 1854, and after 1858 the foreign powers insisted this system be extended to the other foreign trade treaty ports. Despite its origins, the Maritime Customs was always a Sino-foreign hybrid institution, and not under the direct control of the foreign powers. In particular, though the new Maritime Customs had an exclusively foreign senior staff in the nineteenth century, it was the Chinese who selected the top Customs officials. Aged only twenty-four, Hart was appointed to establish the Maritime Customs in Guangzhou by the Viceroy of Liangguang, Lao Chongguang.

An early test of the hybrid nature of the Maritime Customs came in 1863, when the first Inspector-General, Horatio Nelson Lay, acquired a small flotilla of steamships in what one British diplomat described as a misconceived attempt “to make China the vassal of England”.5 Lay was dismissed, and in 1863, Hart was appointed Inspector General in Lay’s place. Hart in his diary on Christmas Eve of that year felt no need for false modesty, noting “My life has been singularly successful: not yet twenty-nine, and at the head of a service which collects nearly three millions of revenue, in — of all countries in the world! — the exclusive land of China.”6

Hart held this position for over forty years until 1908, when he went on what was termed ‘home leave’, generally understood to be his retirement. During his career, Hart never wavered from his conviction that serving the Chinese interest benefited Britain as well, and that the two need not be in conflict, though sustaining this opinion required some intellectual gymnastics. In his later years, Hart found himself increasingly powerless to prevent what he considered to be disastrous steps in Sino-Western relations, such as the exorbitant indemnity demanded by the foreign powers after the Boxer Uprising. Though he helped to negotiate the Boxer Protocol settlement, Hart nonetheless wrote privately that “nothing but bad will result from it”.7 China’s difficulties in paying the indemnity contributed to the Wuchang Uprising just a few weeks after Hart’s death on 20 September 1911, swiftly followed by the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

Hart and photography

As Inspector General, Hart was responsible for customs houses across the country. The network under his control expanded hugely throughout the nineteenth century as foreign powers demanded ever-closer trading links with China, rising from two customs houses in 1859 to around fifty by the time Hart left China for the last time in 1908. The foreign-run service was originally responsible only for trade at the maritime treaty ports, but by 1889 the Maritime Customs also collected at a number of landlocked cross-border trading posts. After 1901, the collection of domestic trade tariffs by the largely Chinese-staffed Native Customs came increasingly within Hart’s orbit as well.

Hart found multiple applications for photography within the Customs service, and many staff records included photographs. Customs officers used photography to document new Customs buildings and compounds, allowing Hart to keep a close eye on staff and operations in distant parts of China even after he largely gave up travelling in his later years. The original Chinese Maritime Customs archive in Beijing was destroyed by fire in 1900 during the Boxer Uprising, though a record of the Customs pre-1900 was later reconstituted from files held elsewhere, and some of the photographs held in that Customs archive in Nanjing have now been published.8

Hart also acquired a significant personal collection of photography, mostly of China, as well as a few photographs taken in Ireland, Britain and elsewhere. Some photographs were intentionally collected by Hart, but many were sent to him unsolicited by correspondents, friends and staff who were aware of his interest in the medium. Gifts of this sort began at least as early as 1866, when Hart recorded receiving “a lot of Peking photographs” from M. Champion, and continued after his retirement.9 Most photographs in Hart’s collection were not publicly available, often taken by amateurs. Hart collected and received multiple images related to the Chinese Maritime Customs, depicting customs staff and their families, customs houses and related activities. While there is no evidence that Hart was himself a photographer, he regularly engaged a professional to photograph events and social functions. A meticulous correspondent, Hart preserved photographs sent by family, friends and colleagues updating him on their personal lives.

Most of Hart’s photography collection was destroyed on the night of 13 June 1900, when all the Customs buildings, including Hart’s house, were burned down in the siege of the Legation Quarter of Beijing during the Boxer Uprising. Hart’s private archive, like the rest of his possessions, was lost in the flames almost in its entirety, though a Customs assistant, Leslie Sandercock, was able to take Hart’s diaries to safety. So complete was the destruction of his belongings that when Hart was finally able to contact the outside world, his first act was to telegraph for four suits from London, noting “I have lost everything but am well”.10 It has sometimes been asserted that all the pre-1900 photographs were destroyed, but in fact some survive, including several albums and a number of loose images, whether rescued by Sandercock or previously stored elsewhere.11 Nevertheless, the vast bulk of Hart’s photographic collection was lost, and Hart’s distress at losing it was considerable. Months later in May 1902, an 1899 photograph belonging to Hart was found in the street and returned to him, but Hart misplaced the photograph a few days later, to his “great grief”, not least because one of the foreigners in that photograph had died as a result of the Uprising.12

The Hart Photographic Collection

Much of Hart’s surviving private archive of diaries, correspondence, photographs and ephemera is now held at Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections (QUBSC). The connection between Hart’s archive and Queen’s University began in 1965, when the eponymous great-grandson of the original Sir Robert Hart willed his ancestor’s diaries to the university, stating they were “for the use of students concerned with the history of China during the period of my great grandfather’s lifetime”.13 The estate of the younger Sir Robert Hart passed the bulk of the collection to Queen’s in 1971. Since Hart’s estate was not in possession of all of Hart’s surviving personal archive, certain items including letters and photographs came to the University of Hong Kong in 1990.

The Hart Photographic Collection at Queen’s comprises over 2,500 images, mostly taken in China between 1860 and 1910. Apparently loaded into two trunks at the time of Hart’s departure from China, the photographic collection now amounts to twenty-three original albums and three boxes of glass slides, as well as loose photographs held in boxes and other containers. The core of the Hart Photographic Collection came to Queen’s with the main Hart bequest in 1971, but items continued to arrive until at least as late as 1974, when the librarian at Queen’s noted that “the photographs will be particularly welcome as we have now been able to assemble a fairly substantial collection of them from a number of sources”.14 Other parts of Hart’s original photographic collection have been dispersed, as for example an album of 1873 photographs of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing by the Chinese Customs officer Ernst Ohlmer, believed to have been Hart’s and sold by Christie’s in 1987. A further set of images in the Queen’s collection relate to the customs official James Wilcocks Carrall, whose daughter Kathleen Newton was Hart’s god-daughter.15

The Hart Photographic Collection has been described as the “most delightful” of the materials relating to Hart, and work is now underway at Queen’s to catalogue and digitise it.16 The collection documents how the foreign-run Customs service reshaped China’s trading infrastructure along Western lines, visible not only in the customs buildings but also in the lighthouses, ports and customs ships. Much of the Hart Photographic Collection is intensely personal, illuminated by scrawled annotations from Hart and his correspondents. The collection also shares many of its themes with similar contemporaneous collections, reflecting the life and preoccupations of a Westerner in China: professional connections to Chinese and foreign contacts, visible in cartes de visite and formal group photographs; the Boxer Uprising and its consequences; and the social life of Beijing’s Legation Quarter.

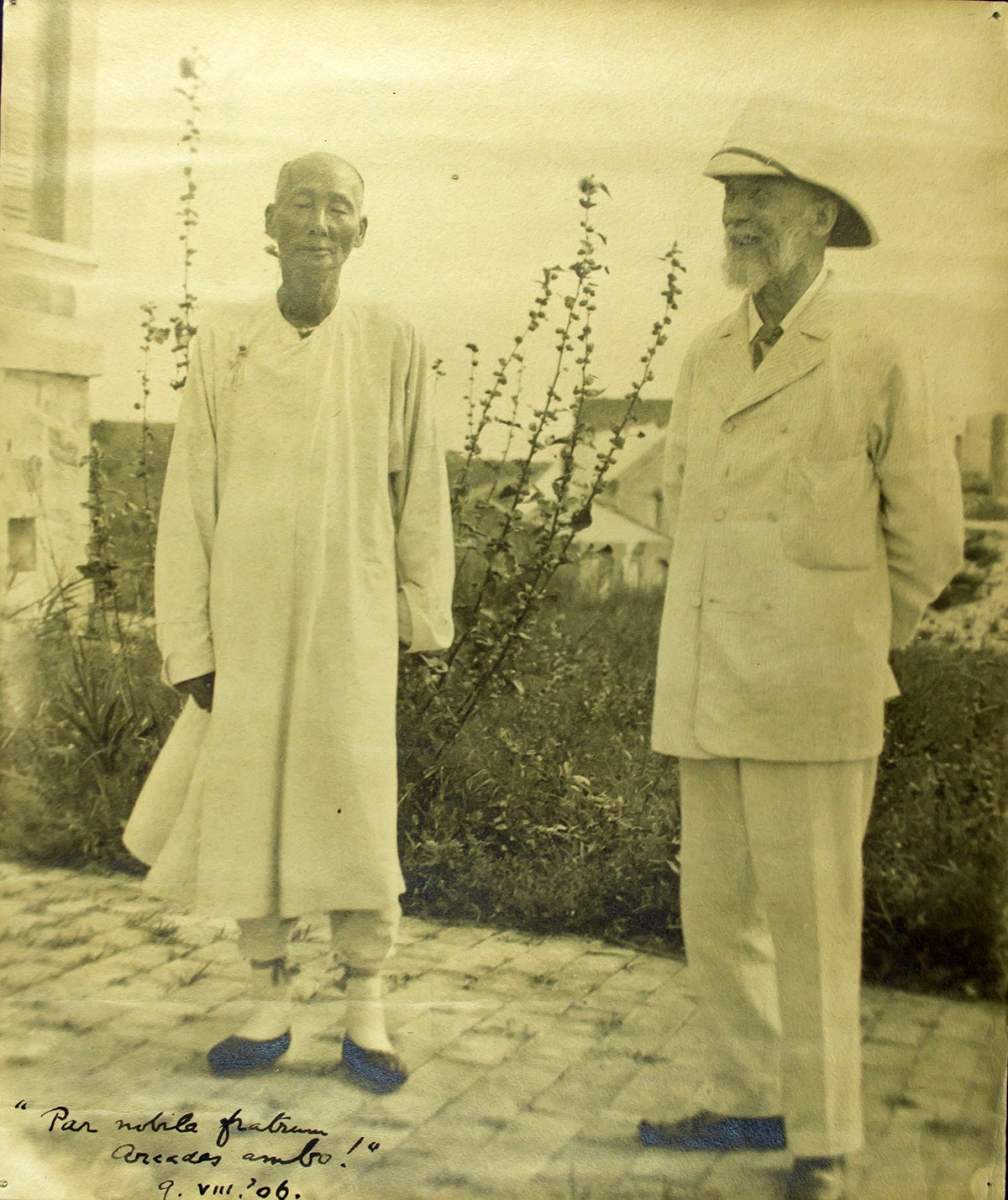

Hart wrote extensively trying to understand this outpouring of violence against Chinese Christians and Westerners during the Boxer Uprising, which he felt to be a kind of betrayal and which left him “horribly hurt”, though physically unharmed.17 Along with his home and his possessions, Hart lost much of his optimism for future relations between China and the West in the Legation Quarter siege. The complex borders of friendship between Hart and the Chinese are also apparent in the photographs. While a few great Chinese officials are documented affectionately in the collection, perhaps the most intimate image of a Chinese is a photograph of Hart with his butler of many decades Chan Afang (also referred to as Ah Fong). Afang had been in Hart’s employment from at least 1863 and, combining Horace and Virgil, Hart captioned the 1906 photograph with “Par nobile fratrum Arcades ambo” [A noble pair of brothers, both Arcadians] (see photo below).

By contrast, Hart’s three children with Ayaou, a Chinese woman who lived with him for much of the period from 1857 to 1866, are entirely absent from the photographic collection. Hart sent his children with Ayaou to England and educated them as his wards, and was sent photographs of them on at least one occasion, but he had no wish to make them part of his family, and made two written declarations of their illegitimacy. Though Hart seems to have been faithful to his wife Hessie and was interested in his legitimate children’s welfare, these relationships were also distant. Hessie left China with their three children in 1882, only returning for a visit twenty-four years later in 1906, while Hart never visited Europe after 1879 until he left China for good in 1908.

The Hart Photographic Collection gives a unique sense of Hart’s personal relationships and of how Hart saw the country in which he lived for almost his entire adult life. Though Hart was mindful of the possibility that his letters and diaries would be published, he seems not to have had any expectation that his photographs would ever reach a wider audience. As such, this collection offers new insights into this complex man and his major role in Sino-Western relations.

Emma Reisz (emma.reisz@qub.ac.uk) and Aglaia De Angeli (a.deangeli@qub.ac.uk), Queen’s University Belfast.

All photos courtesy of Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections (QUBSC).

![Opening of the Yochow [Yueyang] Customs House, 30 April 1901. MS 15/6/5/9. Opening of the Yochow [Yueyang] Customs House, 30 April 1901. MS 15/6/5/9.](/sites/default/files/MS.15.6.5.jpg)