Road Horizons in the Himalayas

A dense network of ancient mountain paths and modern roads connects the communities living in the Himalayas. Recent infrastructure building, carrying different life opportunities, has altered and expanded people’s social worlds while opening new horizons. The road epitomises the state’s governmentality and vision of progress. It sometimes symbolises hope and developmental desire, and large public infrastructure projects often reshape circulatory regimes. For local communities, paths and roads manifest various forms of collective legacies, investment, and expectations which can be political, material, and spiritual.

The constraints and limitations imposed by topography, climate, and ecology are characteristic of the Himalayan experience. The history of human settlements in this mountainous region is intimately tied to various forms of mobility: river valleys constituted natural pathways for the flow of life, and mountain passes supplied the air that breathed life into society. In the Himalayas, people connected through trade, migrations, or pilgrimage and established long-standing economic, religious, and political relations across cultural differences between pastoral nomads or swidden cultivators of the highlands and agricultural communities of the lowland valleys and plains. 1

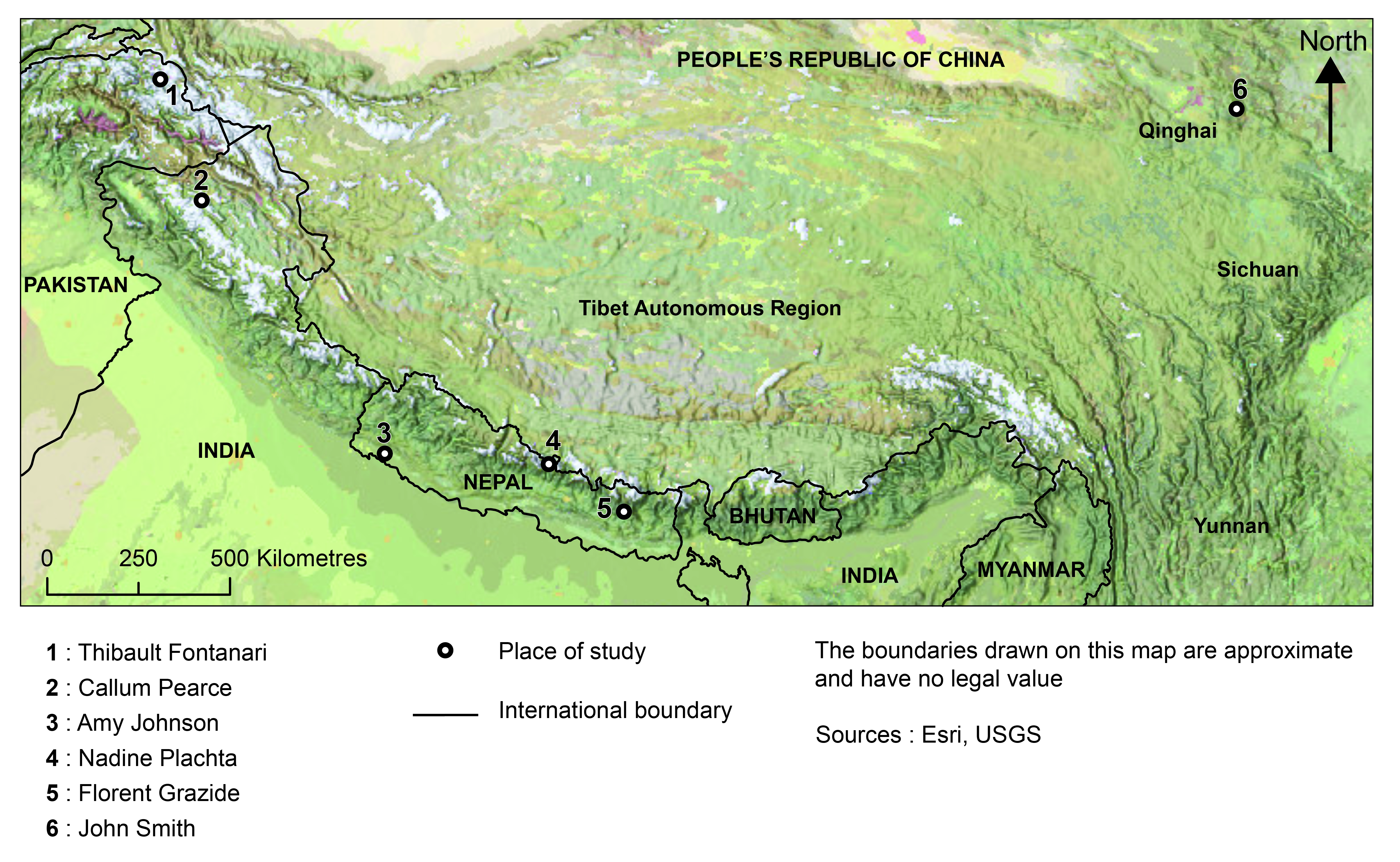

Fig. 2: General map of the area showing the localisation of the case studies in this Focus (Map design by Jérôme Picard).

Along Asia’s highest mountain ranges, from the Pamirs in Central Asia to the great bend of the Hengduan edging the east of the Tibetan plateau, people, goods, skills, and ideas circulated regionally and beyond. Trails and now roads are the connective tissue between communities. This connective tissue is increasingly stretched by changing economic and political conditions that affect how people relate to their environment, move through (un)known landscapes, and maintain a sense of belonging. Today, social and spatial mobilities are increasingly the result of inequalities that they themselves help to (re)produce. However, through their mobile activities, people continue to immerse themselves in particular landscapes and generate their own visions of the future.

Pathways

Many historical variables and uneven temporalities have shaped the complex sociopolitical spatialities of Himalayan communities. This range of hills and high-elevation mountains exemplifies contrasted experiences of mobility and isolation, and the physical landscape greatly determines the routes along which connections can be established. This connectedness – an essential dimension of the Himalayan experience – takes shape, as anthropologist Martin Saxer has argued, along “pathways.” More than connecting lines between locations, pathways constitute “bundles of exchange” that tie together particular places in relation to circulation patterns. 2

In this Focus, a similar inspiration leads us to ask: how can circulations at different scales reveal the ways people inhabit spaces? How do Himalayan dwellers do so according to particular social, economic, or spiritual horizons? We bring together several participants from the “Himalayan Journeys” conference held in Paris in June 2022 3 to highlight how the social life of roads and infrastructure in the Himalayas, from the Karakoram to eastern Tibet, can be fruitfully studied through the lens of the relations people weave between them and with the broader non-human environment. Many avenues for reflection were sketched out on this occasion and our aim here is to provide but a glimpse of particular pathways of sociality that emerge along the trails or roads that traverse the Himalayas.

Infrastructures

Since the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) came into being, the issue of roads and connectivity in the Himalayas and beyond (Highland Asia, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia) has galvanised the fast-growing scholarship on infrastructure. 4 In this Focus, we are interested in infrastructures broadly speaking, whether physical or immaterial, large or nearly invisible, as sites of human encounter and sharing. We look at what they embody, enable, or promise, and how the environment and non-human worlds are entwined in these social processes.

Our purpose here is not to engage with the lively and productive “infrastructural turn” but to pursue a relational and processual approach that investigates how one particular type of infrastructure, the road – that is, an open way that allows for the movement of animals, people, and vehicles – co-constructs the social landscape or the environment at a broader level. In other words, we are interested in what roads can tell us as “stretched-out spaces of social relations.” 5

As many authors have shown, roads and infrastructures more generally tell us about states’ efforts to assert their sovereignty as part of regimes of territorialisation. 6 Here, we write about infrastructure insofar as it reveals the importance of power and social relations without leaving out the non-human and the environment as realms of active engagement. We do not focus on roads in and for themselves, but on what they reveal or generate, on how different kinds of roads affect people differently. Specifically, focusing on the ongoing life of roads and pathways, their accessibility, construction, and maintenance, highlights their temporality, the shifting boundaries between the tangible and the intangible, and the transformative role of hope and futurity.

Roadwork

Building roads has more than ever become a government motto synonymous with connection, development, and wealth, symbolising the current neo-liberal ideology of mobility as a sign of adaptability, autonomy, and agency. There is a common belief that roadless territories cannot embrace globalisation and that tarmac is the visible sign that elected governments take care of local communities who will benefit from new connections with the outer world.

The transformative power of roads is often overestimated. However, when roads are considered as processes, they transform landscapes, create unexpected disruptions in the geomorphology of the mountains, and produce well-documented social effects, whether positive or negative, on people and places.

Fig. 3: The gorge of the upper Salween at the border between Yunnan and Tibet. (Photo by the author, October 2010)

New routes have either replaced historical pathways crossing the Himalayas or created new corridors and have become significant agents of change. The contrast between the mountain path and the asphalted road places them not so much in opposition as on a spectrum of varied instantiation of the visions of the future. 7 To what extent are roads profitable, and for whom?

Besides the geopolitics of road-making as such, what comes across as lacking in the literature is scrutiny of locally lived realities of what is (dis)connected, and how. Several contributions to this Focus explore the complex interweaving of relations between state strategies and rationalities of road building and local practices. The ethnography of local development projects exposes state visions and ideologies that may run counter to local imaginations of connectivity. 8 The articulation of several scales of analysis enabling one to grasp the dialectics of influences and power embodied in the road as a much sought-after infrastructure – sometimes imposed but rarely neutral regarding local power dynamics – deserves further research.

The papers

In this edition of The Focus, our authors build on the basic idea that a qualitative approach brings to light how the various stakes around the movement of people, goods, and skills, as well as the facilitation of this movement, are embedded in geopolitical orders, value regimes, and cultural or ontological frames of reference. They take us along diverse pathways and encounters imbued with fears and hopes.

We generally see infrastructures as what enables the flow and movement of matter in various forms: think of the house and the multiple ways it is connected through lines, wires, and pipes, or nowadays wirelessly to the outside. Under the visible surface, many invisible pathways contribute to the movement of things, people, and other-than-human beings, multilayered webs of connections and circulations. The road can take various meanings – not just metaphorical – and also be a channel for circulating energies and surprising travellers.

This Focus opens with an article by Callum Pearce, who discusses how in Buddhist areas of Ladakh, Himalayan India, spirits or “ghosts” travel along their own invisible roads that correspond to those used by humans by day. For this reason, Ladakhi are concerned with managing other beings’ movement and attest to the potential threat to which ordinary paths and roads are open. This management manifests the potential dangers – real and imagined – to which roads open. Precisely because these lines of travel are openings onto an outside of the safe enclosure of the community, they are sites of vulnerability and risk. They are also, at the same time, the materialisation of social commitments.

In its modern version of the asphalted motorway, the road carries with it all the knowledge and vision of a specific scientific and technological approach to the environment. However, not all built structures rely on similar knowledge and political economy. Here, Thibault Fontanari alerts us to yet another aspect of the invisible dynamics that contribute to the materialisation of built forms and roads in particular: that of the gift and the solidarity it generates. In the Shimshal Valley of Pakistan, we see how infrastructures not only play on the distance and time between things and humans, but more importantly, become the very sites of a collective becoming with profound social and spiritual dimensions.

Circulation pathways can also carry people across time, space, and embodied differences of culture and language. As such, they enable the emergence of new values, of crossings that nurture a longing to become otherwise. What new circuits of belonging can roads facilitate? The next articles switch the narrative to local power structures to illustrate how mobility issues are thoroughly entangled with tensions around divergent visions for the future.

Amy Johnson highlights how sensitive questions around social and spatial origins permeate national and sub-regional politics in the borderlands of Nepal’s Far Western Tarai. She brings an intimate look to this issue by revealing how larger social, political, and gendered dynamics unavoidably shape women’s everyday movements and activities. In the lowlands of Tarai, Indigenous Tharu and resettled Hill-origin persons navigate social differences and diverse legacies of migration. In the context of Nepal’s new federal constitution, passed in 2015, the provinces gained substantial new powers, extending national politics into gendered fields of labour and belonging.

The next two articles also reference the particular context of post-conflict Nepal and the changes that unfolded after the Maoist revolution leading to the elections of 2022. Nadine Plachta shows how, in the Tsum Valley (Manaslu Conservation Area) in Nepal, Indigenous imaginaries and government narratives diverge around the stakes of a new road. But it is not so much a story of clashing visions of infrastructural futures as, rather, that of the emergence, under changing conditions, of a discourse that values and advocates for Indigenous knowledge systems and alternative relations to land and the environment.

As Plachta points out, when countrywide local-level elections were held in 2022 in the Manaslu Conservation Area, people voted for a predominantly Indigenous-led local government. This presents an important step in strengthening self-determined development planning and designing more sustainable and sovereign futures for Indigenous Peoples in Nepal. This echoes Florent Grazide’s description of the evolution of local politics in a small village in the Solukhumbu district. There, the predominantly Tamang population supported one of their own in the local elections so that their voice could be better heard. Again, the promises and failures of a major road project crystallised tensions around questions of belonging, the local interplay of ethnicity or group affiliation, or at another scale, the meaning and prospects of one’s inclusion in the nation-state. However, in this case, what comes to the fore is how local politics is not necessarily shaped by larger issues around Indigenous rights but remains embedded in local power dynamics between kinship networks, ethnic groupings, and party affiliations.

How the state’s project translates into people’s daily lives and materialises (or not) through specific infrastructural projects varies across contexts. The keywords of Chinese development discourse are similar to those of global development and its associated notion of progress, which we also see at play in Nepal. However, they differ in practice, given the nature of state interventionism: China’s massive infrastructure projects are embedded in large-scale, top-down social engineering programmes. Of particular relevance regarding our interest in evolving pathways and the impact of roads is how the state has implemented forced sedentarisation of Tibetan pastoralists and shaped new mobility patterns. As John Smith (a pseudonym) shows in his study conducted among a Tibetan community in the region of Amdo, their horizon has shrunk from the openness of the grassland to that of the linear concrete line, taking them to the city where their life is increasingly anchored. Their sedentarised life entails driving on the newly built road. Paradoxically, its use is made difficult because of the requirement of a government-issued driver’s license, a hard-to-obtain new necessity of life. Here, the rugged terrain no longer constrains mobility, paperwork does.

The footpath and the motorable road inhabit peculiar temporal space: that of walking as a kind of engagement along a mountain path or that of driving on the smooth surface of a road, which likely took decades and may yet remain unfinished – going nowhere. Overall, the contributors to this Focus on “Road Horizons” provide rich ethnographic texture to engage with the questions of the local social imaginaries and practices around movement along particular pathways and the impact new roads can have on the worlds they reshape. They not only highlight the many heterogeneous networks (family, community, market, labour, expertise, etc.) that operate at differing levels beyond the built form of the road. They also emphasise that pathways are always in the making and forever evolving with the broader political, economic, and spiritual forces that shape their destiny.

Stéphane Gros is an anthropologist, a Research Fellow at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS, France), and a member of the Centre for South Asian and Himalayan Studies (CESAH). His work focuses on social change, ethnohistory, and kinship in societies located along the Sino-Tibetan borderlands. Among his recent publications is the edited volume Frontier Tibet (Amsterdam University Press, 2019). Email: stephane.gros@cnrs.fr