The River Cities Network: Engaging with Waterways in the Anthropocene

RCN is a transdisciplinary network, launched by IIAS in 2022, to promote ecologically and socially inclusive revitalization of rivers and the land- and waterscapes, cities, and neighborhoods that co-exist with them. The network brings together scholars, scientists, and activists from more than 30 project teams in the Global South and North, who seek to address local disruption issues confronting the river-city nexus in their areas. RCN’s theoretical innovation is to bring together a (natural science-based) focus on strengthening biodiversity with a (humanistic and social science) focus on environmental and social “justice” in the quest to revitalize these waterways. The RCN teams engage with, and learn from, each other in the process of working towards their river revitalization goals. For more information, visit the RCN website.

The River Cities Network Celebrates Its First Anniversary

Almost one year after the inauguration of the River Cities Network (RCN) in December 2022, RCN partners gathered face-to-face in Bangkok from 25-27 November 2023 for an internal roundtable discussion focused on network matters and an external workshop focused on the changing situation of waterways in Bangkok. Forty-two RCN team members and advisors participated in the internal roundtable meeting, representing RCN project teams in Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Australia, China, Taiwan, India, Iran, Egypt, South Africa, Brazil, Serbia, Bulgaria, Albania, and Italy. For the external workshop, the RCN participants were joined by an audience of Thai activists, students, and scholars. On the program were presentations on the Bangkok water management context by Dr. Thongchai Roachanakanan, former Head of the Climate Change and Natural Disaster Management Center of the Town and Country Planning Department in Thailand, as well as a presentation on canal-side settlements by Dr. Boonanan Natakun, the Bangkok RCN partner from the Urban Futures Policy Unit at Thammasat University. On the second day of the external workshop, all participants travelled to the riverside community of Bang Kachao for a day of fieldwork. See the accompanying story in this spread. The workshop was expertly hosted by a team of local activists and researchers from Thammasat University, Mahidol University, and Rajamangala University of Technology (Thanyaburi). The organizing team was headed by Dr. Kittima Leeruttanawisut, an urbanist and steering committee member of the Sustainable Mekong Research Network.

RCN achievements during the first year

During the internal roundtable the RCN partners took stock of achievements in the first year and discussed next steps in the development and organization of the network.

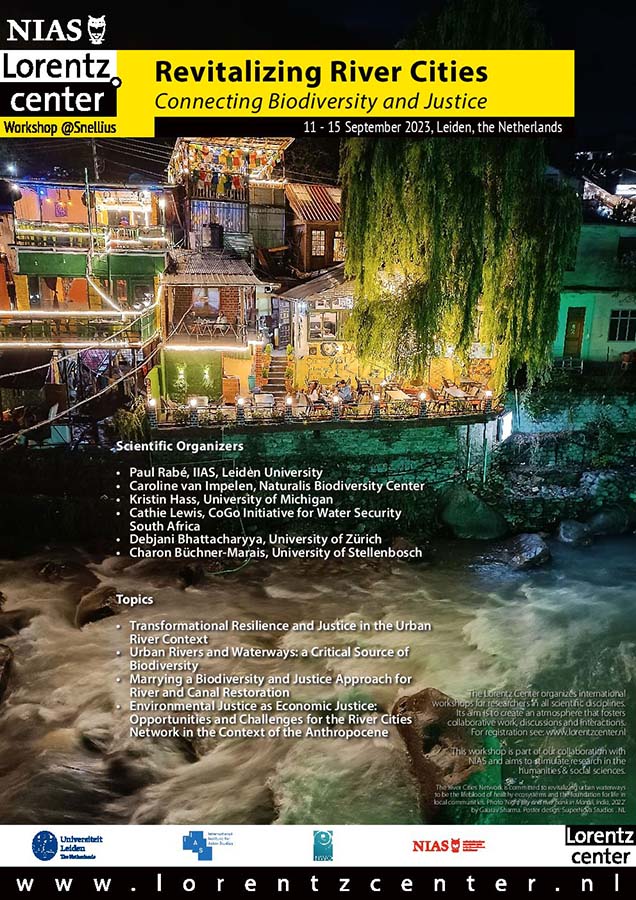

The highlights of the first year of the network included a hybrid theory-building workshop in September 2023, in collaboration with the Lorentz Center in Leiden, entitled Revitalizing River Cities: Connecting Biodiversity and Justice [Fig. 2]. The workshop brought together RCN partners, advisors, and external experts from the biosciences, social sciences, and humanities to discuss theoretical frameworks and practical tools to bring together the two pillars of RCN – i.e., transformational resilience ('justice') and biodiversity restoration, specifically in the context of urban rivers and waterways. The workshop was guided by two main questions: First, how can perspectives from biosciences and social science/humanities intersect in the context of urban rivers and waterways? Second, what tools and methods are essential in a mixed approach that combines a focus on biodiversity and justice to achieve the revitalization of these waterbodies? The workshop yielded insights on both questions that will be piloted in upcoming RCN activities.

Fig. 2: RCN Lorentz Center workshop poster (Sept. 2023).

At the end of September 2023, IIAS funded a six-day intensive In Situ Graduate School (ISGS) for RCN in the city of Padova, Italy on the regeneration of the ancient inland waterway network and the re-imagining of their ecological, social, and cultural functions in the contemporary urban context. The hosts of this ISGS were the RCN’s project team in Padova, based at the Department of Biology of the University of Padova, led by Alberto Barausse. Discussions revolved around the health of the canal system and the manner in which urban regeneration plans shape social well-being, meaning-making, sustainable practices, and cultural representation. Participants of the school were early career scholars from the RCN network and beyond, from 15 countries. The guest lecturers were a distinguished team of scholars and experts from across the disciplines, including biologists, geologists, geographers, economists, historians, engineers, and the UNESCO Chair on Water, Heritage and Sustainable Development at the University of Venice, Professor Francesco Vallerani (also a member of the Padova RCN team). For more information on the RCN Padova ISGS, please read the story on p. 51 of this issue of The Newsletter.

Outputs of the internal roundtable

In Bangkok, the RCN roundtable participants signed off on a new “manifesto” that reflects the network’s values, approach, and methods (see text box). This manifesto is intended to be dynamic and will be adapted by the RCN partners over time as the network develops.

While there are still some ‘wild’ rivers that do not show obvious signs of human intervention, the majority of the world’s rivers are now engineered, socio-natural assemblages. As such, they typify the broader phenomenon of the Anthropocene, an era in which humans have profoundly disrupted the planetary environment in both intentional and unintentional ways. […] The RCN aims to provide generative guidelines that can inform international projects and help communities, researchers and governments that are concerned with the relationship between rivers and urban communities.”

—Excerpt from the RCN manifesto, available in full at https://www.rivercities.world/manifesto

The RCN partners also agreed to create four new groups, each centered on a key theme: (1) river health; (2) living cultures of rivers and waterways; (3) governance, development and planning; and (4) riverine communities. These four groups reflect project objectives of RCN teams and will bring together teams working on these thematic areas across continents for regular exchanges of news and insights and for joint activities.

Bang Kachao

The highlight of the external workshop, on day two of the RCN Bangkok meeting, was a day of fieldwork in Bang Kachao, a peninsula formed by a meander in the Chao Phraya River in Samut Prakan province, just south of the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority (BMA) [Fig. 3]. Bang Kachao is an old settlement, home to a mix of Thai and Mon communities, with smaller populations of ethnic Chinese and Muslims. The area has long been known for its fruit orchards: the brackish water – a mix of fresh water carried down-river by the Chao Phraya and sea water moved up-river by the tides from the Gulf of Thailand – and the rich soil are ideal for the cultivation of many varieties of fruits. An intricate canal system transports the brackish water around the peninsula to irrigate the orchards. Bang Kachao residents have always been proud of their reputation as “the best urban oasis in Asia.”

Fig. 3: Aerial view of Bang Kachao. (NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Public Domain.)

Community representatives welcomed the opportunity to host the RCN participants in their neighborhood to engage in a discussion on the complex disruption issues currently facing their canal system and orchards, in the hope that this could help yield insights, lessons, and suggestions for Bang Kachao based on the international context and experience of the RCN teams. The discussions took place at the Bang Kachao organic farm, an enterprise and community center located in the heart of the peninsula. They hope that the outcomes of the joint fieldwork can help them as they proceed with their local activism. For the RCN partners, the fieldwork in Bang Kachao presented an opportunity to apply – as a group – their transdisciplinary approach and methods to a complex challenge around the deterioration of urban waterways, in conversation with community representatives [Fig. 4].

Fig. 4: Making krathongs at the

Bang Kachao organic farm.

As an advisor fortunate enough to witness the culmination of efforts during a three-day meetup, the experience was nothing short of inspiring.

The event served as a melting pot where diverse perspectives merged into a collective force for positive change. As individuals from various backgrounds, projects, different parts of the world, and expertise levels came together, it became evident that the common thread weaving through the tapestry of the gathering was a genuine passion for river cities.

—RCN Advisor Ereeny Yacoub (Egypt)

What is the future of the largest urban oasis in Asia?

The challenges currently facing Bang Kachao mirror those of Bangkok as a whole. A river delta city once crisscrossed by canals and known to the world as the “Venice of the East,” Bangkok has in the past 100 years been transformed from a city living with water to a city that has undermined its waterscape. Most of the city’s canals have been filled in for roads, and orchards have made way for urban development on a massive scale. Bangkok can today be identified as a land-based city in a watery, deltaic landscape.

The land use control plan for Bang Kachao officially declares the peninsula as a “green area,” which provides some legal protection from land use change. But the protection offered by the land use control plan contains loopholes, which private sector developers are keen to exploit. The peninsula is under increasing pressure from urbanization: on all sides, Bang Kachao is increasingly surrounded by high-rise buildings. Large developers are rumored to be biding their time until the loopholes allow them to assemble land for big commercial projects on the peninsula.

To address these concerns, the government has introduced new measures to buy abandoned orchards and to transform them into parks, to keep the peninsula green. But how “green” and socially sustainable are these measures when they create natural areas devoid of community activity? Another threat may come from within, as one by one, small farmers and landowners are selling their orchards and converting the land to make way for small guesthouses and restaurants. Bang Kachao is increasingly on the tourist trail, as it is becoming a hub (ironically) for green tourism. The increasing urbanization is putting a strain on the traditional canal system, as many canals are destroyed and filled in.

Another disruption occurred about 30 years ago, when the government built a flood barrier around Bang Kachao, supposedly to protect the area from river flooding. As a result of the barrier, an area that flourished for centuries on tidal water and periodic flooding that brought in brackish water is now suffering from excess salt water, with excess seawater now trapped in the peninsula and unable to be flushed out by the tides. Water gates in the barrier remain closed. The combination of growing land use change and the flood barrier are threatening the remaining orchards in Bang Kachao, and both developments are upsetting a delicate ecosystem that has depended for centuries on brackish water. Residents and farmers report an alarming decline in plant and animal species, including the firefly, which the community has adopted as a bioindicator species given that its numbers have plummeted with the combination of external pressures on the local ecosystem.

Fifteen years ago, community leaders established a center to record the health of the firefly as a bioindicator species in Bang Kachao, and also to raise awareness among community members and local schools about the disappearance of the firefly and other endemic species. Community members initiated firefly preservation efforts, recognizing the significance of this species as an important indicator of water quality. Subsequently,

they began daily monitoring of water quality. Over time, they have also undertaken various other activities, such as safeguarding rare tree species for flood protection and negotiating with the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority to secure recycled water for their plants.

Engagement with Bang Kachao community representatives

The RCN fieldwork day in Bang Kachao was organized around four main challenges, which constitute core problems faced by the community. All four challenges are inter-linked, but these four challenges were selected because they require special attention. RCN participants were divided into groups corresponding to one of the four challenges and corresponding to their own professional interests and experience. Each group was led by a member of the local organizing committee and accompanied by a member of the Bang Kachao community, who served as guide for the local context.

A first group focused on (legal and illegal) land use change. Questions included: What can be done to ensure that steady urbanization based on land use conversion does not further destroy local livelihoods (small farming) and the local canal system? And what is the role of land use planning instruments? A second group studied the flood barrier and excess saltwater. Questions here included: What can be done to mitigate the damage done to the local ecosystem and society from the flood barrier? (How) can local farmers adapt to the new ecosystem presented by the flood barrier, characterized by excess salt water, in their farming practices and traditions? A third group looked at socioeconomic changes, asking, among other questions: To what extent are residents of Bang Kachao (and particularly the young people) still committed to maintaining the orchards and the canal system, and what can be done (and by whom) to help preserve local traditions and lifestyles around the orchards? And a fourth group studied biodiversity loss [Fig. 5]. Questions for this group included: What can be done to halt or even reverse biodiversity loss in Bang Kachao, in the face of structural changes to the local ecosystem? (How) can existing community efforts be strengthened?

Fig. 5: Fieldwork by the

biodiversity group in

Bang Kachao.

At the end of the day, the four groups presented their observations and findings to the Bang Kachao representatives. This was followed by a spirited discussion that considered various scenarios for the future of the peninsula [Fig. 6]. Community members vowed to continue their struggle to keep farming in Bang Kachao and to put pressure on the government to keep the river water flowing in and around the area. RCN partners concluded that the Bang Kachao example vindicates the network’s approach to consider the revitalization of river and canal systems in combination with socio-economic, cultural, and political dimensions, as the health of urban waterways and rivers is so clearly linked to the fate of local communities.

Fig. 6: Plenary discussions at the

Bang Kachao organic farm.

Perspectives from Bang Kachao community representatives

What future do you envision for Bang Kachao?

My dream is for Bang Kachao to become the “firefly island.” If fireflies thrive here, it ensures good air quality for residents, positively impacting Bangkok’s air quality. While I may not witness this in my lifetime, I hope the next generation continues this work.

—Sukit Plubchang, Firefly Preservation Group, Bang Kachao

What are your main goals with the establishment of this farm?

Primarily, this farm aims to utilise organic agriculture as an environmental management approach connected to a zero-waste strategy. So, the central goal and the main reason for the establishment of this farm is environmental management. We also focus on other aspects, such as carbon management. We plan to establish a carbon bank within the organic agriculture network to generate additional income for farmers besides their income next to farming.

—Taweesak Ongiam, Owner of Bang Kachao Organic Farm

Paul Rabé is the Coordinator Asian Cities Cluster at IIAS. Email: p.e.rabe@iias.nl