The Restored Splendours of Timurid Samarqand

Down through the centuries, Samarqand, situated in present-day Uzbekistan, has inspired poetic superlatives for the richness of its location, its flourishing economic and cultural life, and its dazzling architecture. Often described as the pearl of the Silk Roads, Samarqand is one of the oldest cities in the world situated in the Zarafshan Valley, the cradle of the intercultural exchanges along the Eurasian trade routes.

During the time of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BCE) Samarqand was the capital of the Sogdian governors and merchants, who controlled the trade from Imperial China to Byzantium until the 11th century. In 329 BCE, the city was conquered by Alexander the Great and adopted the Greek name of Marakanda. Subsequently, Samarqand was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic dynasties until the Mongol invasion by Chinggis Khan in 1220. Even though the city’s history is very ancient, much of what attracts us to Samarqand today traces its origins in the era when the Central Asian conqueror Timur/Tamerlane (d. 1405) built his capital there around 1370. Timur’s successors, notably starting with his grandson Ulugh Beg (r. 1409–1449), continued to adorn the city with monumental buildings. By the 19th century, when we begin to get foreign travel accounts, drawings, and photographs to document the state of the monuments, most of the great structures were in ruins [Fig. 1]. Plans to rebuild or restore some of them were developed as early as the first Soviet years, but the most significant projects were not implemented until the last third of the 20th century, beginning in the years prior to Uzbekistan’s declaration of independence in 1991.

Fig. 1: Postcard depicting the state of the monuments at the turn of the 20th century. Postcard author’s collection.

The Shah-i Zinda Necropolis (11th-15th century)

The Timurid necropolis of Shah-i Zinda (The Living King) commemorates the Muslim martyr Qutham ibn ‘Abbas (d. 677) who allegedly died in Samarqand trying to convert the local population. The complex is situated north of the city, on the southern slope of Afrasiyab, the oldest occupied hillside with archaeological layers dating back to the middle of the first millennium BCE. The necropolis is one of the most sacred pilgrimage sites across Central Asia. The first structures at Shah-i Zinda including mausoleums and a royal madrasa (Islamic religious school) date back to the Qarakhanid dynasty (840–1212). The current complex consists of several mosques and mainly one-chamber mausoleums built after 1350, most of them dedicated to Timur’s amirs (military commanders) and female family members. The ensemble comprises three groups of mausoleums: lower, middle, and upper connected by four-arched domed passages locally called chartaq. All facades along the main corridor are covered with lavish revetments employing ornaments executed in different techniques: carved majolica, glazed terracotta, polychrome overglaze and monochrome glazed ceramic, and tile mosaic. In particular, mosaic faience, was perfected under the Timurids after the 1390s, and some of the most exquisite examples are found at Shah-i Zinda. These tile revetments also protect the structures erected with baked brick from constant temperature fluctuations (very hot summers and cold winters), rain and dump.

The earliest images of Shah-i Zinda are recorded in the Turkestan Album (1872) commissioned by Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann (1818-1882), the first governor general of Russian Turkestan. Excavations of the site started in 1922 and continued until 1925. However, a systematic approach to the study of its architecture, archaeological layers and history did not begin until 1957 when the excavations were led by Nina B. Nemtseva (1926-2021), who worked at Shah-i Zinda until 2001.

After 2005 Shah-i Zinda underwent a massive restoration campaign throughout which new mausoleums were built. Original Timurid tilework was substituted by modern mass-produced tiling. The remains of the portal to the 11th-century Qarakhanid Madrasa (1066) were demolished. Several Qurʾanic texts (3:169, 3:170) were added to the main entrance portal originally built in 1435.

The Gur-i Amir Mausoleum (late 14th-early 15th century)

The Timurid dynastic mausoleum of Gur-i Amir was commissioned by Timur in August 1404 for his beloved grandson of Chinggisid lineage and heir presumptive Muhammad Sultan (d. 1403). The mausoleum was erected in the southwestern part of Samarqand, adjacent to the pre-existing complex of Muhammad Sultan (late 14th century) consisting of a two-storey madrasa (to the east) and a domed khanaqah (Sufi lodge) to the west. All three structures are arranged around a central open courtyard with a main entrance portal to the north. The octagonal mausoleum is covered with a ribbed dome decorated with turquoise tile mosaic. The interior space is adorned with a dado of octagonal onyx tiles, crowned by a muqarnas cornice. Around the 1420s, Ulugh Beg refurbished the interior and the onyx tiles were gilded with Chinese lobe cloud patterns and lotus palmettes. The upper walls are decorated with papier-mâché details in gold and blue crafted from locally produced paper. The cenotaphs of Timur, his sons Shahrukh and Miranshah, his grandsons Muhammad Sultan and Ulugh Beg, and Timur’s spiritual consort Sayyid Baraka, are situated in the centre of the main mausoleum, surrounded by a carved marble screen. The actual burials and tombstones are in the crypt below, closed to the general public in accordance with Islamic burial rituals, in which the sanctity of the deceased should not be disturbed.

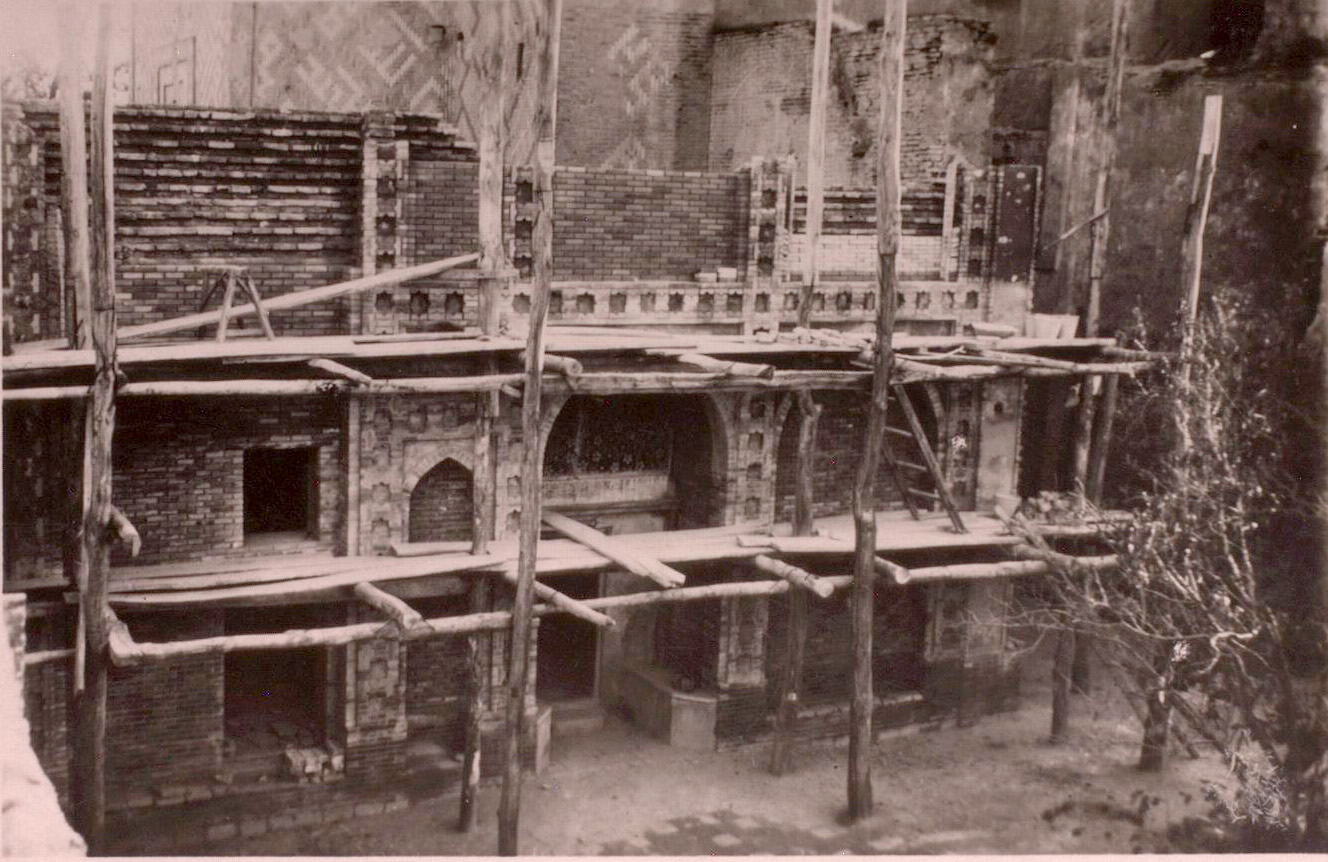

Fig. 2: Construction of the main courtyard façade of Gur-i Amir in 1945. Courtesy of the Central State Archive of the Republic of Uzbekistan (TsGARUz), R-2406, op.1, file 1365, page 13.

In 1425 Ulugh Beg erected a gallery to the east, which serves as the main entrance to the mausoleum. Most likely, this enlarged compound included another gallery to the south, of which only a few arches remain, and a monumental complex to the west with a central domed space. By the end of the 17th century, the madrasa had been abandoned and the dome of the khanaqah had collapsed. The two remaining minarets were also destroyed; the south-eastern one collapsed after a major earthquake in 1886 and the south-western one was ruined on May 18, 1903.

The systematic study of Samarqand’s monuments was initiated in 1895 when the Russian Tsarist Archaeological Commission sent an expedition under the supervision of Nikolai Iv. Veselovskii. The expedition resulted in the publication of the only volume of the lavishly decorated catalogue The Mosques of Samarqand (1905), solely dedicated to Timur’s dynastic mausoleum of Gur-i Amir and financed by Empress Aleksandra Fedorovna (1872–1918). This prototype of an officially politicized edition on Timurid architecture depicted Gur-i Amir as an idealized work of art, stripped of any religious or socio-cultural importance.

During the Soviet period, Gur-i Amir was remodelled in a series of restoration campaigns continuing into present-day. The central courtyard façade was completely redesigned by Galina A. Pugachenkova (1915-2007) and built in 1945 [Fig. 2]. The western remains of the Muhammad Sultan complex were excavated in 1952 by Nemtseva [Fig. 3], partially reconstructed, and the entrance portal to the north was renovated with reinforced concrete. During the celebration of Timur’s 660th jubilee in 1996, the whole ensemble was refurbished and the minarets were erected anew. After 2008-9, new epigraphy was added to the central courtyard façade and many original Timurid tiles were substituted with modern majolica reproductions manufactured in Tashkent. In 2019, the UNESCO Director General Audrey Azoulay visited Gur-i Amir but no attempts were made to stop the constant refurbishments and ongoing demolitions.

Fig. 3: Detail of a tile mosaic fragment from the Muhammad Sultan Madrasa, Gur-i Amir, Samarqand. Pencil drawing by Nina Nemtseva, 1952. Courtesy of the Archive of the Agency for Cultural Heritage (GlavNPU), file C 723/H 50.

Bibi Khanum Mosque and Mausoleum (1398-1405)

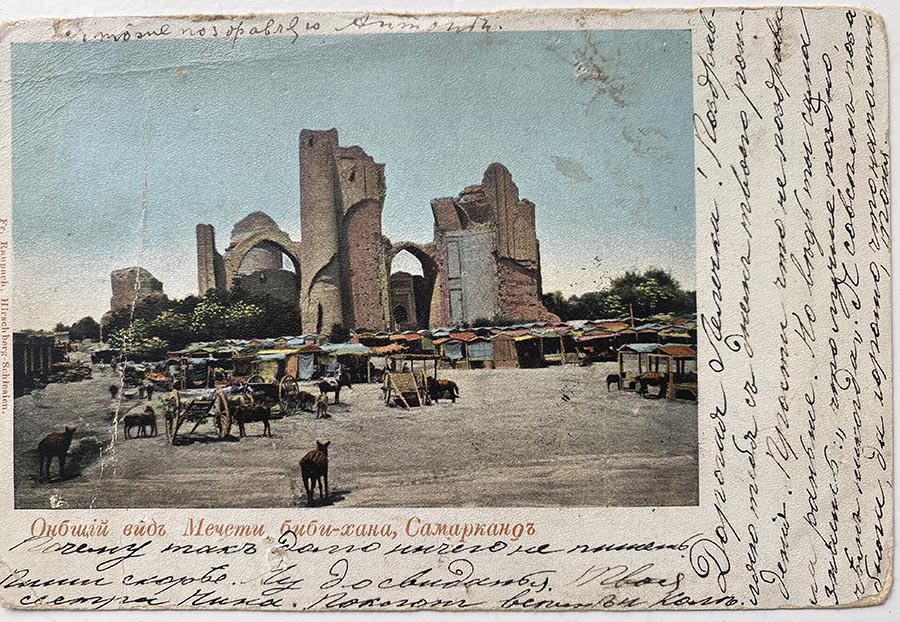

The Bibi Khanum Congregational Mosque (1398-1405) was conceived as the most significant architectural expression of Timur’s rule. The mosque was the most ambitious building project initiated during his lifetime and can be visited today in a 20th-century restoration. It is very likely that the construction was never completed, which can explain the dilapidated state of the monument at the end of the 19th century [Fig. 4]. At the nadir of its decay, it had been reduced to the core of the main sanctuary, its dome having partially collapsed, and the iwan (monumental gate) of its façade consisting of a perilously suspended fragment. The small northern and southern mosques facing on the large open courtyard were also in ruins and without their domes. Nothing was left of the two-storey domed galleries that connected all these elements; only the north-western minaret had survived. According to the description of the Bibi Khanum Mosque in Maṭlaʿ- saʿdayn va majmaʿ-i baḥrayn (The Rise of the Two Auspicious Constellations and the Junction of the Two Seas) by ʿAbd al-Razzaq Samarqandi (1413-1482), masters from Basra and Baghdad modelled the maqsura (enclosure reserved for the ruler near the prayer niche), the suffas (elevations), and the courtyard after structures in Fars and Kirman. Silk carpets covered the open spaces. Craftsmen from Aleppo lit gilded lamps similar to heavenly stars in the inner domes of the mosque. 1

Fig. 4: The ruins of the Bibi Khanum Mosque at the end of the 19th century, view from the east. Postcard published by Fr. Raupach, Hirschberg-Schlesien, 1905. Author’s collection.

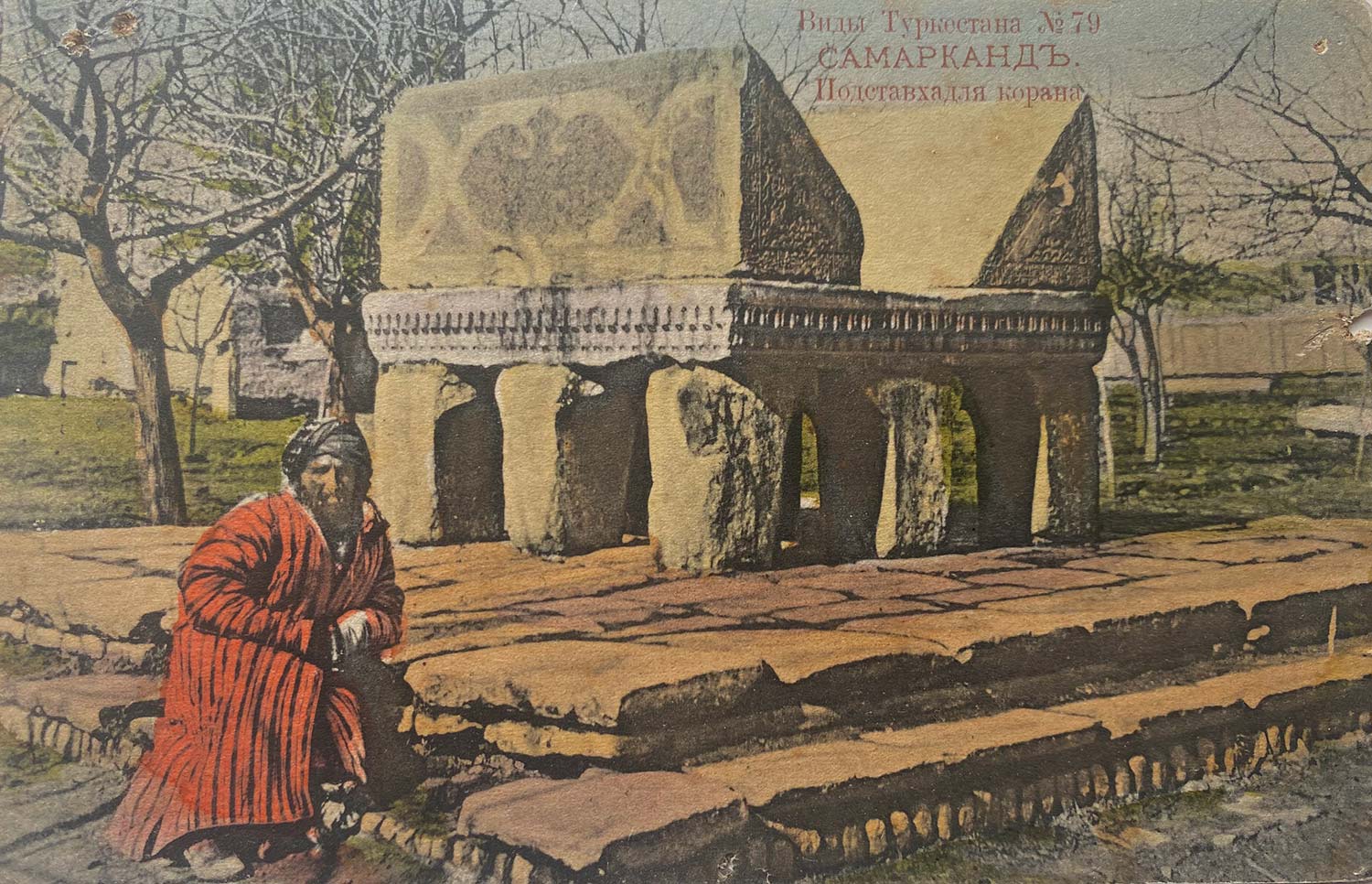

A monumental Qurʾanic stand as a material expression of piety was placed in the main sanctuary sometime after 1420. It was commissioned by Timur’s grandson Ulugh Beg who is believed to have memorized the Qurʾan with all seven variant readings. The stand is made of carved stone in relief and clearly bears his name [Fig. 5]. Its rich arabesques and poly-lobed details can be attributed to the iconography of Yuan porcelain prototypes that may have entered the Timurid court via the active caravan trade between Central Asia and China. With this in mind, China should not be regarded only as a trade partner but as an important source of imperial inspiration and emulation as it was the home of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) established by Kubilay Khan (d. 1294). Timur and his descendants struggled for political legitimacy beyond the legacy of Chinggis Khan (d. 1227). The Yuan as the chief successor state of the Mongol empire may have constituted the most significant source for imperial visual vocabulary that was successfully reappropriated and transformed by the Timurids. Although Zhu Yuanzhang, a humble plebian turned general, succeeded in overthrowing the Mongol dynasty in 1368 and proclaimed himself as the first Ming emperor, taking the title of Hongwu (1328-1398), the continuous significance of the Yuan legacy for the Timurids should not be underestimated. Under Timur, there were several embassies to Ming China. The exchange of royal gifts and the intensity of the trade relations increased under Shah Rukh and Ulugh Beg; the first Timurid embassy arrived in China in 1387, followed by yearly tributes of horses and camels to the Ming court. The first known Chinese embassy to Timur was established in 1395. The Ming chronicles, Mingshi and the Da Ming Yi Tong, and the Ming Geography Shi Si yü ki refer to Samarqand as the “city of abundance,” and mention “a beautiful building set apart for prayer to Heaven” situated in the north-eastern part of the city. It is highly probable that they refer specifically to the Bibi Khanum Mosque which had pillars of “tsʿing shi (blue stone), with engraved figures.” 2 Even today, the stone of the Qurʾanic stand has a blue-greyish tinge to it. According to the chronicles, “there is in this building a hall where the sacred book is explained. This sacred book is written in gold characters, the cover being made of sheep’s leather.” 3 The fact that the Ming chronicles explicitly mention the location of the richly-decorated mosque and refer to a particular Qurʾan, only stress the importance of their artistic qualities and their symbolic association with the rulers of Samarqand.

Fig. 5:. Qurʾanic stand in the courtyard of the Bibi Khanum Mosque commissioned by Ulugh Beg. Photo by G. Pankratyev, 1894. Postcard published by Voishitskii, ca.1907. Author’s collection.

The Bibi Khanum Mosque is also unique for the first usage of papier-mâché in its interior decoration. According to Borodina, the technique was imported from China. 4 The cotton paper was inexpensive, locally produced and sometimes repurposed for decoration. The architectural details were pressed into ganch (a form of local gypsum) moulds and consisted of seven or eight sheets of paper fixed together with starchy vegetable glue. In addition, papier-mâché was the only decoration applied on the interior domes. Each detail of the relief decoration was separately created and attached with iron nails onto the walls in order to form larger compositions. The upper surface of the papier-mâché ornaments was primed with ganch and gilded; the papier-mâché was used to create a relief surface under the gilding. In separate instances, ganch reliefs pasted over with paper were also applied under the gold surface. Examples of the latter practice can be found not only in the Bibi Khanum Mosque but also in the Tuman Agha Mausoleum at Shah-i Zinda and at Gur-i Amir. The Samarqand paper was famous for its quality and durability, and it was even exported. There were paper mills and storage facilities along the water canals (aryks) coming out of the Siyob Bazaar in the north-west of Samarqand.

The Bibi Khanum Mosque was comprehensively studied by Shalva E. Ratiia in the 1940s. Ratiia drew up the first restoration plans based on its ruins and produced reconstruction watercolours. Pugachenkova finalized the restoration plans for the mosque at the beginning of the 1950s. Further archaeological research was performed by Liia Iu. Man’kovskaia in 1967. After 1974, the restoration project was led by the architect Konstantin S. Kriukov, one of the most influential restorers in the Soviet period, who initiated the replacement of all brick loadbearing structures with reinforced concrete frames. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the collapsed domes of the side mosques were rebuilt with reinforced concrete and new tiling was inserted along the domes’ ribbed outer shells. After 1985, the main sanctuary was adorned with massive pylons, decorated in mass-produced tiles. By the end of the 1990s, the epigraphic programmes were executed anew; two verses of Sura al-Baqarah (Qurʾan 2:127-128) were added on top of the main sanctuary iwan of the Bibi Khanum Mosque.

During the urban regeneration of Samarqand prior to the 2007 celebrations of the city’s 2750th anniversary, the whole square between the Bibi Khanum Mosque and the Bibi Khanum Mausoleum (early 15th century) was completely refurbished. In 2005-6, the octagonal mausoleum, which had been reduced to ruins, was adorned with a new pseudo- Timurid dome on a high drum and rebuilt facades with arched portals. The outer wall of the Bibi Khanum Madrasa was built up above ground level with modern brick to replicate the presumed position of the original guldasta (corner towers). Although no traces of the madrasa remain, Soviet scholars have stylistically compared it to the Ulugh Beg Madrasa on Registan Square.

The Registan Square (15th-17th century)

Although the present layout of the Registan Square evolved during the 15th-17th centuries, the current state of the three madrasas (Islamic religious schools) is the product of numerous restoration campaigns. The northern and southern facades of the Ulugh Beg Madrasa (1417–1420), the oldest surviving monument on the square, were piles of rubble at the beginning of the 20th century. Thus, its entire courtyard had to be rebuilt and the epigraphic program designed anew.

The characteristic hauz (water tank) to the southeast was destroyed. One of the western minarets collapsed in 1870. In the autumn of 1918 it was noticed that the north-eastern minaret of the Ulugh Beg Madrasa had started to tilt. As a result, a lot of engineering effort went into the straightening of the original minarets along the Registan. The first reconstruction project was initiated in 1920 by Mikhail F. Mauer, the chief architect of Samarqand since 1917. After a decade of preparations, the north-eastern minaret was straightened in 1932 by the Moscow engineer Vladimir G. Shukhov. In the 1950s, E. O. Nelle produced the drawings for the straightening of the south-eastern minaret, the work was executed by the engineer E. M. Gendel in 1965.

The earliest restoration work at the Shir Dar Madrasa (1616-1636), the second oldest monument on Registan Square, was carried out by Boris N. Zasypkin and started in 1925. Unlike his later Soviet colleagues, in the 1920s, Zasypkin was pleading for “restorations aiming at supporting the ancient fabric of a monument and reconstructions substituting its lost structural parts.” 5 Zasypkin was never in favour of reinventing the architecture of the Samarqand monuments and interfering with their medieval constructions by introducing new building materials. He insisted on collaboration with local craftsmen and masons, and on the usage of the original baked brick and locally produced alabaster.

What had been little more than a shell with a facade of the Tilla Kari Madrasa (1646-1660), the Shaybanid Congregational mosque from the 17th century, was completely re-built by the Soviet authorities. The much-photographed dome one sees today was added during a long restoration campaign that ended in the late 1970s. There are no existing photographs of the original dome that collapsed after a major earthquake in 1818. Its spectacular gilded interior was restored in 1979.

In 1982 the Registan was revealed to the Soviet public in its presumed former glory, and the restoration team lead by Konstantin S. Kriukov honoured. The later Soviet restorations focused mainly on the rebuilding of the three Registan madrasas with reinforced concrete.

As the main scientific adviser, Kriukov, believed that the exterior decoration was a sheer garment worn by the construction itself. Thus the refurbishment of all Registan madrasas with newly manufactured glazed tiling was merely a question of efficiency. The reinforced concrete dome shells were a manifestation of Soviet technological progress that would ensure the longevity of the madrasas beyond the frequent tremblors of Central Asian earthquakes.

Conclusion

With its rich cultural history, favourable climate, and verdant gardens, the oasis of Samarqand has always triggered the imperial ambitions of powerful rulers along the Silk Roads. They constructed their capitals there, erected mausoleums to commemorate their ancestors, and decorated the city with monumental mosques and squares. The impressive architecture of Samarqand is the product of prolific artistic exchanges combing and reinventing visual vocabularies brought to the city by captured craftsmen and enslaved builders originating from Damascus to Isfahan. However, motifs and skills were not directly reappropriated but were instead transformed in accordance with local Islamic aesthetics, availability of materials and building traditions. The westward transmission of Chinese designs was further encouraged by the thriving artistic, political, and commercial exchanges between the Ming and the Timurid courts in the first half of the 15th century. These creative endeavours resulted in a sophisticated and unique cultural production across the Turco-Persianate world. Unfortunately, the majority of the buildings and their decoration have suffered from the continuous earthquakes and historical vicissitudes that have marked Central Asian ever since. Some have been permanently lost, others have been heavily restored in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Dr. Elena Paskaleva is an assistant professor in critical heritage studies at Leiden University. She teaches post-graduate courses on material culture, memory, and commemoration in Europe and Asia. Dr. Paskaleva is also the coordinator of the Asian Heritages Cluster at the International Institute for Asian Studies. E-mail: elpask@gmail.com