Local societies in Asia have long been known for their persistence in the face of an all-devouring developmentalism. They have championed their own traditions – sometimes in the name of heritage, more often not – and have seen in these a way of resisting the forces that threaten to uproot them and destroy their lives, values, and everyday practices. They have doubled down on the insistence that they, not the bureaucrats and politicians, represent the true culture of the place where they live.

In this volume, an eclectic agglomeration of case histories, we have collectively explored the idea that, in the Asian context at least, resilience has itself become an important form of heritage. It is perhaps one of the most intangible-seeming of heritages, but the reality is that its effects have often proved remarkably tangible. While the forms of resistance to authority this resilience has fed have frequently ended in failure, the afterglow of pride and dignity may fuel more imitations, more refusals of bureaucratic insensitivity and corporate greed, more demands of recognition for the diverse modernities that challenge the hegemony of the nation-state and rampant consumerism. It has become important to see resilience itself as a form of heritage.

If resistance becomes a watchword for revolutionary societies, resilience may instead signal a degree of conservatism – but not the conservatism of the corporate state. Resilience is about human dignity, which involves human agency in making decisions and choices. Resilience is not merely about keeping a roof over one’s head, but about being able to choose the design of that roof, to maintain a physical and cultural framework that gives familiarity and meaning to everyday life while also allowing opportunities to explore new ways. So while resilience may entail conservatism, this is also not the conservatism that refuses all forms of innovation. Indeed, true resilience entails innovation that nevertheless respects the styles and needs that rest on past experience.

Allied to the concept of resilience is that of community. We recognize that community is a very generic term that, for that reason, has been widely criticized as vague. Yet it is also true that groups of people find in their shared sociality – as well as in forms of artistic production that defy larger conventions – a sense of a specific identity tied to a place, a practice, or a worldview. In this generic sense, community stands in for those forms of belonging that rest on the right to do things together, and, simply, to be together.

We recognize that this sense of community is not peculiarly Asian. Indeed, it is important to transcend stereotypical and essentializing distinctions between Asian and “Western” societies. Our concern is not with “Asian resilience” but with “resilience in Asia” – and specifically in the easterly reaches of the continent, where the uneven interplay of colonialism and global capitalism with an astonishing variety of ways of achieving community offers an especially fertile context for thinking about what constitutes resilience and vernacularity.

In these pages, Steve Ferzacca in particular also debunks the tangible-intangible distinction, arguing that heritage is above all a social construction that arises from the intersection of various layers of identity formation – including, but not privileging, that of the nation-state (which in the case of Singapore entails a nation of multiple ethnicities temporarily, arbitrarily, joyously dissolved in a salad that in its very heterogeneity serves as a model of the resilient disorder that people recognize as both vernacular and heritage). The mini-Bildungsroman that Ferzacca narrates – how a visiting anthropologist from Canada finds the common cultural and musical threads that lead him to participate in a durable activity that is at once social, cultural, sensory, and aesthetic – alerts us to those moments of clarity in which it is the act of recognition that constitutes heritage and strengthens its potentiality just to be, to exist, at the happy confluence of overlapping personal, cultural, and social trajectories.

Resilience is everywhere. Sometimes it opposes authority; at others, it takes the form of an equally creative obedience. Sometimes it arrests visual appearance through acts of reasserting a collective tradition in the face of official disdain or of appropriating official versions of heritage for local consumption. Sometimes it is a refusal to fit into new, bureaucratic forms or official identity politics aimed at consolidating state power. It is about adaptation, collective self-recognition, recognition by others. Sometimes it is starkly conservative, at others innovative and riotously flexible. Recognition is, perhaps, the key to those moments when something comes tangibly into focus and then demonstrates an unexpected capacity to resist the anonymizing and leveling effects of time.

Resilience is about what people do together, whether as an ad hoc jamming group, an equally ad hoc agglomeration of families from different points of origin (as in Pom Mahakan, Bangkok), or the cultural cosmopolitanism that opposes that of the nationalistic state and proves an enduring source of local solidarity (as in Melaka, discussed in the accounts of both Kim Helmersen and Pierpaolo De Giosa). The act of doing something together can take the form of tactical cooperation between several households to face a common threat, as we see in Marie Gibert-Flutre’s observation of residents’ efforts to increase resilience to floods in Ho Chi Minh City. Or again it can emerge in an organized effort of several communities to preserve collective memory through events and new rituals in the midst of an industry-driven environmental disaster such as that observed by Anton Novenanto and I Wayan Suyadnya in Porong, Indonesia.

Often, as Tessa Guazon shows, it emerges in works of art that, in the face of natural disasters, depart from official representations of the smiling nation and instead assert – the performative act of assertion should be a key term in any consideration of resilience – more localized forms of identity that resist the homogenizing effects of official discourse; these also transcend the self-other splits that so often result from ethnic and national politics and thereby produce new forms of reciprocity. Works of art, also the focus of Motohiro Koizumi’s writing on site-specific and socially engaged art, may become avenues to encourage community participation, allowing individuals to express themselves through a collective art project. If Helmersen’s analysis invokes Émile Durkheim, Guazon’s seems – reciprocally? – to conjure up the ghost of Marcel Mauss.

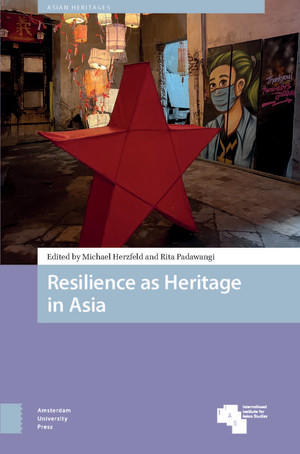

Performative and collective acts of assertion as resilience constitute a key theme shared across all chapters and the book cover. Not taken from any of the chapters in the book, the cover photo represents a form of resilience as a collective effort: a community hall and various artworks at Tambak Bayan, a neighborhood in Surabaya, Indonesia, that is at some risk of eviction after a long land dispute. The community has developed networks with academics and artists, local and international (including hosting events and visits during the ICAS 13 ConFest in 2024, Fig. 1). It is an assertion of the residents’ collective existence in the neighborhood space.

These perspectives reinforce the sense that resilience itself can appear as a form of heritage. Herein perhaps lies a danger, that of essentializing resilience as a peculiarly local (or national, or Asian) property. Instead, in rejecting the idea of a homogeneous “Asian resilience,” we prefer to treat resilience as a heritage of humanity. That, perhaps, offers the best reason for the deliberate eclecticism of our volume – an eclecticism that is itself an act of resistance and resilience in the face of the normative expectations of academic publication. We wanted to do something different; and here it is.

Michael Herzfeld holds Emeritus positions at Harvard and Leiden Universities. His twelve books include Siege of the Spirits: Community and Polity in Bangkok (2016) and Subversive Archaism: Troubling Traditionalists and the Politics of National Heritage (2021). His current research addresses heritage politics, crypto-colonialism, and artisans’ practices of competition and cooperation.

Rita Padawangi is Associate Professor (Sociology) at Singapore University of Social Sciences. Her research is on social movements, community engagement, and environmental justice. Rita coordinates the Southeast Asia Neighbourhoods Network (SEANNET), a collaborative urban research and education initiative. She recently published Urban Development in Southeast Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2022).