Repurposing Phnom Penh: An Interdisciplinary Framework for Archive-Based Education and Intervention in Cambodia

Since its independence from the French colonial power in 1953, Cambodia has experienced decades of turmoil and transformation. War, political transition, and reconstruction have left their imprint on the landscape, particularly in the capital Phnom Penh. Yet, the question arises of what remains of these traces today as the city’s rapid growth results in limited heritage preservation. What role do archives play in this context of fast-paced urbanization? Can they become a ‘field of intervention’ for young Cambodians? If so, what types of archives are we talking about? The workshop “Repurposing Phnom Penh” sought to answer these questions and, in the process, address the broader theme of the ‘archive’ (as institution, collection, and praxis) in Cambodia. It took place in Phnom Penh in September 2024 with a group of students from different disciplinary backgrounds. The workshop aimed to show that archives do not only contribute to a better understanding of the past. They may also enhance citizen participation in contemporary issues such as urban planning.

As in other countries that went through long periods of conflict and destruction, the ‘archive’ has been an ongoing topic in post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia. The first institutional attempts to recover or preserve devastated collections, produce new records, and train staff occurred in the 1980s. New types of institutions emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s, in the wake of the 1992–1993 UN mission in Cambodia (UNTAC) and the country’s democratic transition. The Center for Khmer Studies (CKS), the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), and Bophana Center for Audiovisual Resources, to name but the major ones, reshaped the archival landscape. However, while they have made collections more easily accessible to the public, bringing young Cambodians to archives remains a challenge to this day.

Against this backdrop, the workshop tried to develop interdisciplinary pedagogies that would help students become more familiar with archive institutions in Phnom Penh and also become more autonomous in their future research projects. “Repurposing Phnom Penh: Built Forms and Infrastructures as Archive” (hereafter RPPP) was developed with CKS in partnership with the Royal University of Fine Arts (RUFA) and Bophana Center. 1 It proposed to explore Phnom Penh’s urban history with a focus on the repurposing (or re-use) of the city’s buildings and infrastructures from the mid-1950s to the mid-1990s. The concept was elaborated by myself (CKS Senior Fellow) with artists and curators Vuth Lyno and Khvay Samnang, whose work has long addressed urban life, architectural heritage, and the effects of development on cities and communities. This core group of facilitators was joined by anthropologist Anne-Laure Porée (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales or EHESS, France).

By investigating what was or wasn’t built, what was or wasn’t re-used by a broad range of actors such as governments, communities, NGOs, and individuals, and what has survived and how in the present-day cityscape, we wanted to produce a bottom-up, socio-material ‘portrait’ of Phnom Penh and its residents over 40 years. The precariousness of the city’s tangible and intangible heritage (buildings, lifestyles, and ecosystems) motivated our choice of this urban lens. We thought it made archives all the more significant and could foreground the idea that, far from being a thing of the past, archives can foster critical engagement with the present.

Our objective was to stimulate the students’ critical appropriation of materials and get them used to working with an ‘expanded’ archive including textual, audio-visual, and material sources. We organized RPPP’s hands-on activities around a concrete goal: the creation of group projects about Phnom Penh. These projects were to be presented to the public at Bophana Center on the last day of the workshop. They could take any form – photo, performance, video, sound piece, installation, object, or social media piece – as long as they used the resources explored during the workshop and were produced within RPPP’s time and budget constraints.

RPPP took place in Phnom Penh between 10 and 14 September 2024 at RUFA and Bophana Center. We were aware that a sprint workshop might be too short given the program we had designed. Yet, we thought that an intensive experience could be transformative for the students – and for ourselves. We also made it clear from the start that RPPP was experimental, without any guarantee of ‘successful’ outcome since its aim was to develop pedagogies.

The workshop was held in Khmer, with occasional interactions and interventions in English. On the first day, we introduced the themes and objectives. Lyno and Samnang presented their work to give the students examples of what we had in mind. After that, we proceeded to group formation. We had selected 20 students from different universities and with different disciplinary backgrounds (architecture, archeology, fine arts, and engineering). The group was homogenous in terms of age (20–23), and it had a good gender balance. We thought it was best to let the students self-organize with little prompt from our side. We only asked them to use two Post-it notes, a yellow one where they had to write their main skills and a green one where they wrote their main interests. After sticking these on their chests, we invited them to stand in the middle of the room so that they could move, read the information, talk, and finally assemble according to skill complementarity and affinities [Fig. 1]. This social aspect was essential. Prior to the workshop, the students had never met, but they quickly bonded and formed friendships, which we hoped would become the basis for future collaborations between them.

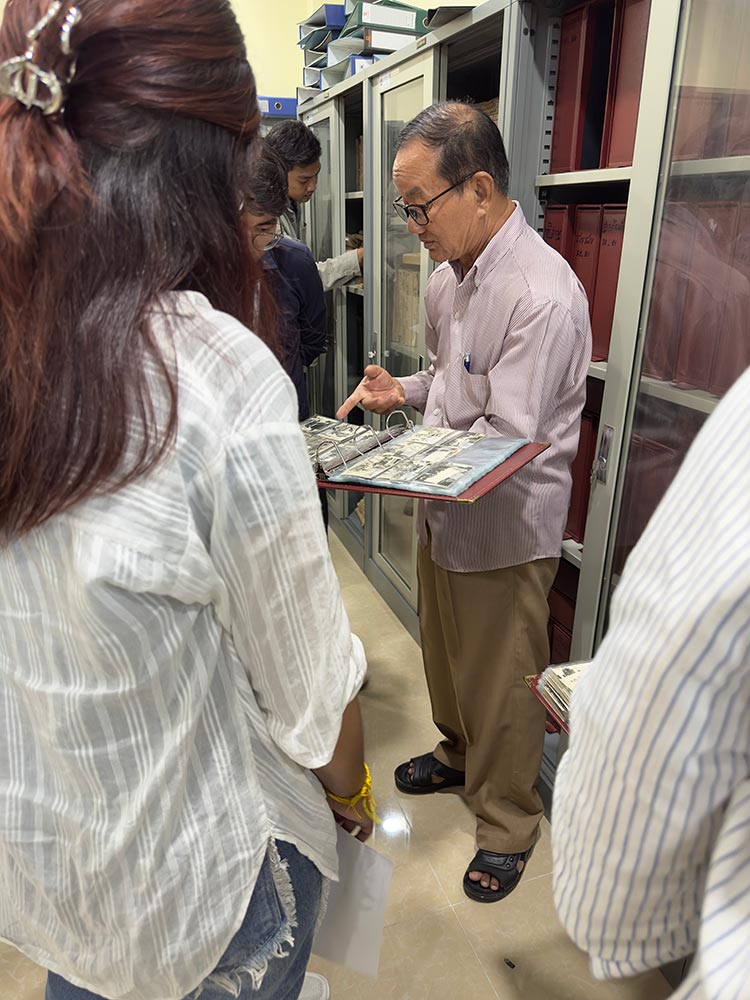

Fig. 2: Visit at the AKP archive. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2024)

The workshop alternated between studio work and trips to archive institutions. We visited the Khmer Press Agency (AKP) in the Ministry of Information, the National Archives, and Bophana Center. As agreed with these institutions, each participant could choose up to two items in the collections for their group project. This stimulated exchanges within the groups. The AKP was particularly interesting for the students, as many did not know that such an archive existed. The photographic collection gave them unique insights into Cambodia’s reconstruction since 1979 [Fig. 2]. At the National Archives, the students were introduced to the institution’s history and collections. They observed how the staff members clean the documents [Fig. 3]. They also visited the upper floors and thus understood better the structure of this French colonial-era building (1926). At both sites, the students met elderly archivists who have worked in these institutions for decades and could tell many stories. These encounters were, for both sides, an important moment of transgenerational transmission.

Fig. 3: Cleaning of documents at the National Archives. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2024)

The program included site visits as well. We first saw two French colonial-era buildings on the Post Office square (1894). One now houses a restaurant; the other, bought by a developer, is fenced and, for the moment, left to rot. On Lyno’s suggestion, we went to the former Pasteur Institute located in Chroy Changvar, on the outskirts of Phnom Penh [Fig. 4]. This veterinary hospital, a concrete three-story building, was designed by architect Vann Molyvann (1926–2017) in the mid-1960s. It is a good example of “New Khmer Architecture,” the hallmark of Cambodia’s post-independence modernization. Abandoned during the Khmer Rouge period, it was re-occupied as housing after 1979. This community (mostly people with low-income jobs) has remained there. Our guide was dancer and choreographer Nget Rady, who has been living in the building since his parents settled there in the 1980s. The Pasteur Institute and its residents are now threatened by development. From the rooftop, it is possible to see the advance of high-rises encroaching from all directions.

Fig. 4: Pasteur Institute. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2024)

The last stop was Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum (TSGM). Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge had used these school buildings as a prison under the codename S-21. In 1979, the new authorities converted the site into a memorial museum. Anne-Laure, an expert on S-21, was our guide for the visit. We started with the 3D map of S-21 to show the students the prison’s actual size and configuration (beyond the museum’s five buildings) and the transformation of the neighborhood over time, as buildings have been reclaimed for housing and commercial purposes. The second part of the visit focused on the role of the museum’s photo archive in research and exhibitions. Anne-Laure explained to the students how the TSGM staff had used details on pictures (window shape, broken tile) to identify the exact torture rooms featured in the photos taken by the Vietnamese troops when they entered the compound in January 1979 [Fig. 5]. 2 The visit ended with a discussion on the two memorials in TSGM courtyard, the memorial of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) with the names of all identified S-21 victims (2015) and French-Cambodian artist Séra’s sculpture To Those Who Are No Longer Here (2015). 3

Fig. 5: Torture room, Building A, Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2024)

It was the first time some of the students visited TSGM. Knowing that such an experience might be overwhelming, we had planned a moment in the afternoon to talk about it with them. We also thought it would be a good idea to focus, for the rest of the day, on a different subject – in that case, how everyday practices and ‘poor’ materials can be treated as archives, too. This was the topic of the online keynote given by anthropologist Kathrin Eitel, from the Department of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies (ISEK), University of Zurich. Her talk, entitled “Circular Researching as a Method for Making Sense of the Urban Fabric,” addressed waste management and recycling in Phnom Penh. Kathrin discussed her methodologies, more specifically what she calls “research cycle,” or the process of coming back to the research object through multiple lenses, from different perspectives, and with renewed questions. The students quickly adopted the concept and often referred to it when they described their projects.

From the third day of the workshop onwards, Bophana Center became our second home. The students spent hours watching archive footage and worked on their projects. It was a period of lengthy conversations with the facilitators. We tried to help them move, as Samnang said, ‘from balloon to rock’ – that is, to drop huge, infeasible plans for low-tech, manageable proposals. They setup their work on the last day. RPPP concluded with the public presentation of the four group projects: Build your Own Monuments, Connect Lives, Echoes of the Water, and Living Facades. The event was well-attended with over 80 visitors. Each group had 10-15 minutes to present their project, followed by a Q&A with guest discussants architect Roeun Virak and independent curator Moeng Meta.

With this workshop, we hoped to change the students’ relationship with archives in many ways. Our first objective was to provide them with some methodological training that could help them navigate research in archive institutions by themselves. Our second objective was to transform their conceptions of what can be or become an archive, and thus of their potential role as archivists. We wanted the students to realize that anyone can be responsible for preserving, retrieving, and highlighting forgotten or under-documented stories. We also hoped that RPPP would help the students learn new skills, especially in terms of teamwork – how to assign tasks, work together under pressure, schedule and budget a project, negotiate and compromise. Lastly, we thought that the public presentation would be a good opportunity for them to go out of their comfort zones and, in the process, discover capacities they did not think they had.

The group projects confirmed that our objectives had been reached – and exceeded. The students threw themselves into the workshop wholeheartedly, sometimes working into the evening, well after the ‘official’ end of the day. Their installations-performances were the result of hours of reflection and discussion on what they had seen and how to present it. Their reports gave us further indication of what RPPP had achieved (or not). Most students expressed interest in continuing to document vernacular, communal, and everyday forms and spaces, thus producing archives for the future. Moreover, they considered archives as a significant source of inspiration for the creative design of friendlier public spaces and sustainable lifestyles. They also saw how a good knowledge of the past could help them become informed citizens with a louder voice in public debates on Phnom Penh’s urbanization. The learning process was mutual. We started the workshop with some ideas of pedagogies. Their application ‘in real life’ showed what worked and what could be improved. For example, the students said they would have liked more time for onsite observation and interviews, or – not a big surprise given all the work they had put into their projects – a small exhibition instead of a one-evening presentation. The next workshop will integrate these elements and, hopefully, offer another stimulating framework for young Cambodians to experiment with archives.

Stéphanie Benzaquen-Gautier is a visual historian, currently a Research Fellow at IIAS. Her work explores violence, archives, memory, and activism in Cambodia. Email: sd.benzaquengautier@gmail.com

Repurposing Phnom Penh: The Projects

Living Facades

Siborey Sean, Rattanakpisal Tan, Sokchoung Lim, and Sreyneang Chheng

Our project explored the evolution of Phnom Penh’s iconic shophouses in response to changes in Cambodia since the country’s independence [Fig. 6]. Shophouses are a distinct feature of Southeast Asian urban architecture. They are not unique to Cambodia and can be found in countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia as well. Originally designed as multipurpose spaces for living and commerce, these structures reflect a rich history of cultural exchange and colonial influences. In Phnom Penh, shophouses have undergone dramatic transformations, particularly in their facades. Over time, these facades have been adapted and modified to reflect shifting economic conditions, cultural practices, and personal tastes, from vibrant signboards and modern materials to improvised extensions and additions. We decided to create an interactive model showcasing these changes and invite the public to engage with them. The use of cutouts depicting facades, people, objects, boards, and plants allowed the visitors to actively ‘remodel’ the shophouses and, in the process, become virtual homeowners reimagining their environment. Gamification was central to our project. It encouraged playful exploration while fostering a deeper understanding of the ongoing adaptation of urban living spaces. Public reactions were positive. Many visitors expressed their newfound appreciation for the resilience and creativity inherent in Phnom Penh’s cityscape. Some people shared personal experiences and insights which highlighted their emotional and cultural connections with these spaces. Our interactive model worked as both an educational tool and a mirror for societal transformations. It revealed how, through their houses, people perceive and adapt to challenges such as crises, economic booms, and ideological shifts. This underlined the importance of documenting these changes as part of Phnom Penh’s living history.

Fig. 6: Living Facades (Photo courtesy of the “Living Facades” team, 2024)

Echoes of the Water

Taing Chongsan, Top Viphallin, Lay Chariya, and Keo Chhornlyly

Our project examined community spaces along the Phnom Penh riverside. It sought to highlight the tension between urban development and traditional fishing practices. The idea came from the archive materials we discovered during the workshop, especially the 1957 footage “Fishing in Cambodia” (Bophana Center). We were struck by the traditional structures fishermen used to dry their nets, and by the communal spaces where they gathered. Many of these traditional activities have now disappeared from the cityscape, supposedly because of hygiene and safety issues. Of course, this footage portrays a romanticized view of riverside fishing. It overlooks fishermen’s physical exertion and economic uncertainty, or the environmental risks. Yet, it also celebrates their sense of community and resourcefulness. We wanted to revive these memories of traditional fishing practices while commenting on the effect of urban development on communal spaces. We first thought about building small-scale models that would reproduce these spaces. In the end, we decided to create a larger, immersive project enabling the visitors to experience the material elements and atmosphere of the vanished riverside communities [Fig. 7]. The installation featured a fishing net canopy supported by bamboo. To build it, we also used the fish sculpture Trey Reach on display at Bophana Center. We incorporated historical photos of fishermen gathering, chatting, laughing, and interacting with water bodies. We created a series of drawings that evoked the contrast between tradition and modernity. For example, one drawing shows a fisherman and boats set against a riverside community on one side, and a modern ferry framed by a towering city skyline on the other side. For the performance, three team members walked through the installation and presented the drawings to the public while the fourth member told the story from the fish’s perspective. Through this specific viewpoint, we tried to give a ‘voice’ to endangered species and show the interconnectedness of all living beings. Overall, the project was a reminder that the river is not just part of the environment but a lifeline for many living beings. We tried to raise awareness of urbanization’s ecological impact on both humans and nonhumans, and therefore of the need for a more inclusive perception of community spaces.

Fig. 7: Echoes of Water. (Photo courtesy of the “Fish” team, 2024)

Connect Lives

Keo Tephnemoll, Khan Kunsovann, Heng Rathanaksambath, Heng Sivma, and Kaing Thanaroth

During the workshop, we grew more and more interested in the ways everyday life, heritage, and modernization interact and how time shapes this interaction. We became particularly engrossed in the evolution of marketplaces. What fascinated us was the presence of contrasting yet culturally connected elements of past and present marketplaces. Sales prices have now gone up, and malls have appeared everywhere in the city. Yet, when it comes to traditional street food culture, some markets remain the same, whether it is at the Central Market, the Kandal Market, or the Russian Market. This inspired us to imagine interactions between people from different timelines and merge histories in order to uncover shared experiences. Our project’s title, ផ្សារជីវិត (Phsar Jivit), a wordplay in Khmer, reflects this dual meaning. According to the Choun Nath Dictionary, as a noun, it means a market, and as a verb, it means to weld or link. A picture by photographer John Vink (Bophana Center) gave us the context for the installation. It shows a citizen selling boiled duck eggs on a busy market sidewalk in 1989, a rather common sight then. We combined materials collected from the archives with recent images to create a series of photocollages about market life over two generations. To emphasize overlooked continuities, we imagined people from the past who encounter today’s technological world and, conversely, present-day people who discover past lifestyles. The installation, at Bophana Center’s entrance, recreated a boiled duck egg booth, with the photocollages in the background [Fig. 8]. For the presentation, we reenacted the sale and consumption of these eggs. At the end, visitors could grab an egg or two for the price of 500 riels ($1.25 USD). Nostalgia played a significant role in our project. Some visitors recalled their experiences of market life and food. For younger generations, though, it was something new. People’s emotional engagement with our project highlighted the importance of bridging between past and present to ensure a meaningful future for cultural traditions.

Fig. 8: Connect Lives. (Photo courtesy of the “Connect Lives” team, 2024)

Build Your Own Monuments

Morn Mab, Pav Lydoeun, Phea Sreynoch, Song Seakleng, and Tum Chankrisfa

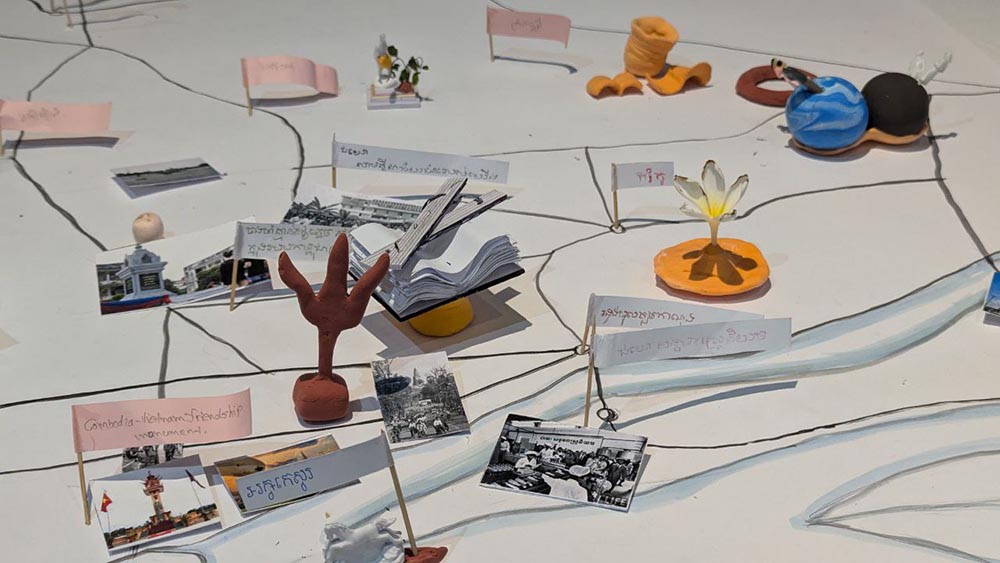

Our project tried to challenge traditional notions of monumentality as something top-down and static. Instead, we wanted to rethink monuments as dynamic and participatory structures that can reflect Phnom Penh’s diversity and ever-changing history. Our idea was to invite visitors to make monuments that would represent their personal memories and aspirations and could be added to existing ones. Archives provided the resources for this concept. The collections we explored not only shaped the project’s design. They encouraged us to reassess how past events and figures have influenced the cityscape. As a result, we created an interactive installation where people could express their own identities and stories. We drew a map of Phnom Penh with basic information. Visitors could use colorful clay to shape their own monuments, then write quotes holding personal significance on small paper flags which they could pin on the clay and finally place their monuments on the map [Fig. 9]. People really enjoyed the project. For example, a visitor built an eggplant that represented his province (Takeo). It was his response to the provincial authorities’ idea of using a balut as a regional symbol. He wanted something that expressed his own vision of it. We presented the map with a short, critical video about the evolution of monumentality in Phnom Penh since independence. The work combined views of the city’s informal spaces with footage of monuments built by Cambodian leaders at different periods. It ended with images of Phnom Penh’s most recent monument, the Win-Win Memorial, and its inauguration in 2018. The soundtrack blended ambient city sounds, popular music from these periods, and more reflective tones. With this project, we tried to show to the public that the cityscape is a living archive and it can be reinterpreted as a more inclusive space of making and sharing memories.

Fig. 9: Build Your Own Monuments [2024]. (Photo courtesy of the “Build Your Own Monuments” team, 2024)