Representation of Asia in Contemporary Australian Politics, Media and Everyday Life

According to the latest figures from the Bureau of Statistics in 2016, the Asian-born population in Australia accounted for 10.4 percent of the total population. 1 This raises a range of issues in regard to the representation of Asian Australians in politics, the media, and other key areas of everyday life. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has seen a resurgence of racist remarks by right-wing politicians and growing anti-Asian sentiments and violence in public space. As Australia shut its borders to and from international travel in an attempt to stop the virus entering Australia, many Chinese – or Chinese-looking – migrants and international students, who were misconstrued as a source of the virus, became the target of racially-motivated violence. Due to the ongoing national border closures, many international students were forced to continue their studies offshore and online for two consecutive years.

In 2020, a group of researchers affiliated with the Gender, Environment and Migration (GEM) Cluster at the Asia Institute of the University of Melbourne in Australia examined various aspects of the representation of Asian Australians in the context of contemporary Australia. The collaborative work was published as a Special Issue of Melbourne Asian Review in March 2021, 2 and it includes an examination of issues relating to political under-representation and media portrayals of Asian Australians as well as the state of Asian-Australian studies.

Many would wonder about the definition of “Asian Australians.” Unlike Asian Americans, a widely-used term which also has an established field of study in sociology, media, literature, and cultural/racial studies, the history of Asian Australians is relatively short compared to analogous groups in the Americas or Europe. We use the term “Asian Australians” in reference to a diverse population comprising individuals who have migrated from the Asian region. The term is widely accepted and used in Australian social, political, and cultural discourses. Many Asian Australians we included in our studies are first-generation immigrants or international students who just arrived in Australia. Furthermore, many Asian Australians elected to the Australian parliaments are of mixed heritage that includes both Asian and European ancestries. As the demographic composition of the Asian-born population in Australia changes, our definition may change over time going forward.

Fig. 1: Melbourne’s Chinatown at night (Image reproduced under a Creative Commons licence courtesy of Russell Charters on Flickr).

One key issue is the ongoing, well-documented lack of representation at all levels of public life. A lack of diversity on the small screen 3 is paralleled in the political domain, where Asian Australians are under-represented in federal and state parliaments. Only 3 candidates with Asian ancestry were elected in the 2019 federal election. Difficulties in the pre-selection process can be an obstacle to greater engagement of candidates from diverse language and cultural backgrounds. 4 Based on interviews with Australians of Indian origin – some of whom had been successfully elected to office and others not – Surjeet Dhanji recommends that Australian political parties should address the “representation gap,” initiate programs to close that gap, and harness the talent of those currently underrepresented. 5

Although underrepresentation occurs at the level of politics, the pandemic has resulted in the continued hyper-visibility of Asian Australians, as manifested in increased anti-Asian racism. Hyper-visibility refers to the ways in which minoritized groups are over-represented in overwhelming negative ways. Qiuping Pan and Jia Gao, for instance, indicate widespread experiences of racism against Chinese immigrants. 6 The most common manifestation of such racism involved racial slurs and/or name-calling. Such incidents are also heavily gendered, with women lodging 65 percent of the COVID-19 Racism Incident Reports between April 2-June 2, 2020.

The relationship between the state and society has changed over the course of the pandemic. State responses to the global pandemic at a local level have direct and indirect consequences on minorities, especially Asian migrants in Australia. In order to understand changing state-society relations during and after the pandemic, trust in both the government and different media sources is an important area to study. In this regard, Wonsun Shin and Jay Song’s online survey of 432 Asian Australians illustrates how much they have relied on traditional media (e.g., mainstream TV) and how little they relied on ethnic language programmes. 7 In spite of anti-Asian racism, the survey respondents showed a high level of trust in Australian governments. Others reported that Asian Australians are more likely to be anxious and worried due to COVID-19, and they have experienced “twice the drop” in work hours as other Australians. 8

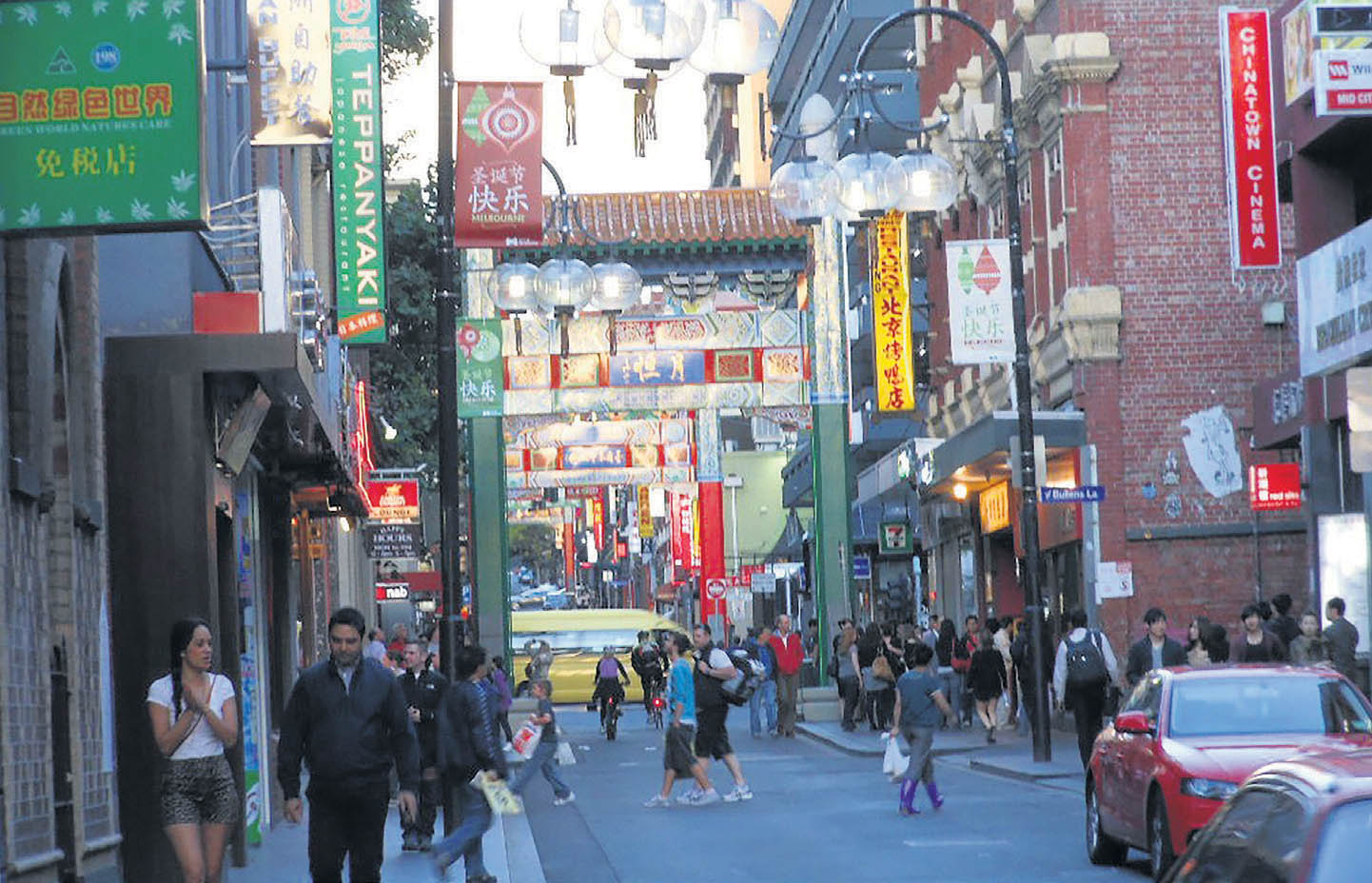

Fig. 2: Melbourne’s Chinatown (Image reproduced under a Creative Commons licence courtesy of Michael Coghlan on Flickr).

Asian Australians are highly diverse and constitute a fluid group that is being constructed and reconstructed by interactions among its members in an increasingly complex, mediated society. Studies on Asian Australians, therefore, require an intersectional and multi-dimensional approach to fully understand the challenges and opportunities of engaging with the fastest-growing population in Australia. One such example of an intersectional approach on Asian Australians taken by members of GEM examines sexual citizenship. This approach illustrated how gender, sexuality, and ethnicity influence Asian migrants’ experiences in post-marriage equality Australia. 9 The authors point to the necessity of critical reflexivity for the study of migration in contemporary societies.

As stated earlier, Asian migration to the Americas and Europe has a longer history, and studies on Asian diasporas are already an established field. Even though the field is relatively new in the Australian context, the nature of contemporary transnational Asian migration to Australia – from the arrival of Europeans to a hub for cosmopolitan highly skilled Asian migrants – has greater implications for scholars not only in migration and ethnographic research, but also gender, media, and inter-cultural studies.

Claire Maree is an Associate Professor and Reader of Japanese Studies at the Asia Institute, University of Melbourne and President of the International Gender and Language Association (IGALA). Email: cmaree@unimelb.edu.au

Jay Song is an Associate Professor of Korean Studies at the Asia Institute of the University of Melbourne and Deputy Editor for the Asian Studies Review. Email: jay.song@unimelb.edu.au