Religious exclusivism in Malaysia

Malaysia’s Islamic elite have been promoting conservative and exclusive ideas lately. This group consists of individuals trained in the religious sciences, and includes muftis (state-appointed persons with religious authority), ulamas (religious scholars), popular preachers, religious teachers and religious bureaucrats.

Academics and human rights activists in Malaysia have associated this elite with Wahhabi-Salafism (puritanical brand of Islam). For example, Marina Mahathir, a women rights activist, opined that Malaysia was undergoing an Arabisation of Islam because the way the Malays dress, behave, and think no longer reflected ‘Malay identity’. Prominent sociologist Professor Syed Farid Alatas also argued that extremist ideas from the Middle East have influenced the ulama’s thinking and behaviour. The Sultan of Johor, Ibrahim Iskandar, recently criticised Malaysian Malays for imitating the Arabs, declaring, “If there are some of you who wish to be an Arab and practise Arab culture, and do not wish to follow our Malay customs and traditions, that is up to you. I also welcome you to live in Saudi Arabia.”

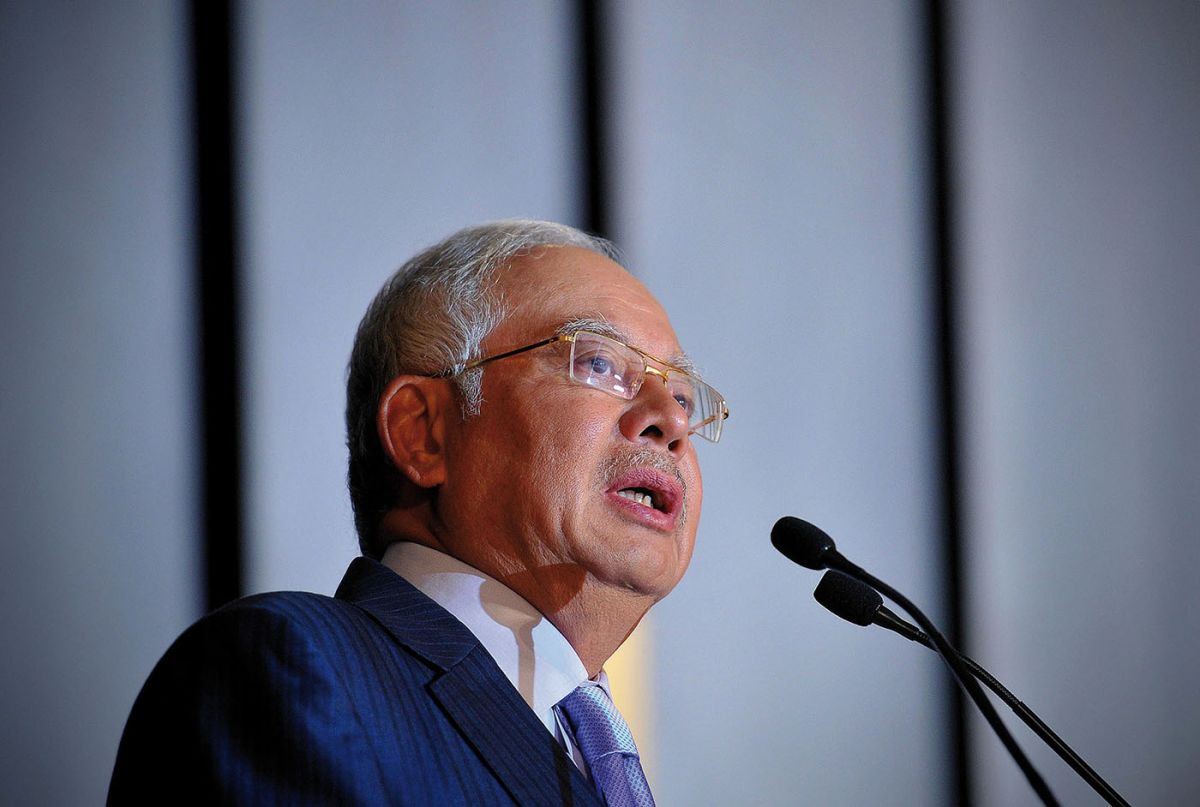

By contrast, Malaysian Prime Ministers Abdullah Badawi (2003-2009) and Najib Razak (2009-present) have portrayed Malaysia’s brand of Islam as a moderate one. However, recent controversies involving the Islamic elite, such as book bans, the persecution of religious minorities (the Shias), and the prevention of non-Muslims from using the word ‘Allah’, do little to support notions of Muslim moderation. Instead, since 2016, the Najib administration has worked closely with the Islamic opposition party, PAS, to strengthen syariah laws in the country despite protest from opposition parties and other groups.

The influence of Middle Eastern Islam

To what extent has Middle Eastern Islam crept into the Malaysian Islamic discourse? Is it even correct to link the exclusivist attitudes of Malaysia’s Islamic elite with Middle Eastern Islam in the first place? Generally speaking, a case can be made for how Wahhabi-Salafism has influenced the behaviour of some Islamic elite in Malaysia, particularly those who continue to receive their training in Middle East universities. They frown upon the following acts which used to be commonly practised in Malay society: veneration of saints, visitations of graves of saints, and celebrating the Prophet’s birthday. There is greater promotion of Wahhabi-Salafi ideologies by the Saudi Arabian government funded by petro-dollars. Globalisation has also allowed greater exchange of ideas between the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Local and national factors

However, one should never discount local and national factors. In this case, the role of the dominant Malay party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), and the Malay rulers in shaping the religious elite’s political and religious behaviour. In Malaysia there is still a strong emphasis on rituals and mysticism in Malay society with little regard for universal Islamic values such as equality. Hence, blaming the Middle East alone for the country’s conservative bent ignores the historical, institutional, and political conditions under which ulamas function.

The truth of the matter is that exclusivism in Malaysia draws support from wherever it can. What Malaysians need to be wary of is the exclusive faith-based attitude in general. This means being wary of those who are ultra-defensive of particular ideas, who display authoritarian views towards diversity, and who condemn alternative voices as ‘liberal’ or ‘deviant’. Such exclusivist attitudes are found across different theological orientations, be they Wahhabism, Salafism, Sufism, or traditionalism.

In addition, the patronage of Malay rulers remains crucial in defining the political behaviour of some Malaysian muftis. Some scholars have suggested that Wahhabi-Salafi modes of thinking are more marginal to Malaysian society than previously thought. After all, the majority of Malaysian muftis remain Sufis and conservative in outlook, just like the Perak and Negeri Sembilan muftis. The Selangor religious council, for instance, defends Sufi practices that are frowned upon by Wahhabi-Salafists. In fact, the Malay rulers, who are constitutionally the custodians of Islam in each state have consistently backed the Sufi-oriented religious elites.

In some instances, Islamic institutions send mixed signals. For example, in 2014, the Pahang Religious Council banned Wahhabi-Salafism from being preached in the state. The grounds for the ban was that the ideologies sowed disunity among Malaysian Muslims. On the surface it suggests that the religious council was combating exclusivism. However, more recently, the Pahang mufti Abdul Rahman Osman made hostile remarks towards the opposition Democratic Action Party. He declared the party as kafir harbi (non-believers who can be slain) for opposing Islamic laws. He was also quoted to say that working with the opposition party was a sin according to Islam. Again, such exclusive views were not related to Wahhabi or Salafi thought.

Conclusion

In summary, the way forward should be for Malaysian Muslims to be critical of any form of exclusive attitudes in religious discourse, rather than to single out particular religious doctrines. An exclusivist is an exclusivist, regardless of whether he is a Wahhabi-Salafi, Shia, Sufi, Sunni or a self-declared liberal. Common spaces for debate over religious ideas and values are needed.

Norshahril Saat is a Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute (norshahril_saat@iseas.edu.sg).