Regionalism in Southeast Asia: ASEAN’s Potential and Challenges

Southeast Asia, in contrast to the other regions of Asia, has actively pursued regional integration through the formation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Although its institutional nature is different from that of the EU and the level of integration is not as high, most of the countries in the region (10 countries) are members of ASEAN, and the organization has provided the basis for joint cooperation with countries outside the region. The evolution of ASEAN shows how a group of newly independent and relatively weak states that value their sovereignty have endeavored towards regionalism against the backdrop of internal and external security, economic, and regime-related crises and conflicts.

ASEAN was formed as a security response to the spread of communism during the Cold War and evolved by adopting the strategy of leveraging offshore powers while promoting regional cooperation to address the internal and external security and economic challenges of its member states. ASEAN has continued to promote regional cooperation and expand its membership amidst globalization, the China threat, the East Asian financial crisis, and the US-China conflict. In this process, ASEAN has succeeded in promoting both internal integration and external expansion by maintaining the internal principle of respecting the sovereignty of regional states while at the same time asserting ASEAN-centrality. ASEAN is not a highly politically integrated organization with some ceded sovereignty like the EU; rather, ASEAN features a unique decision-making process based on consensus among sovereign states, emphasizing the rights of sovereign states. But this emphasis on the principle of sovereignty has resulted in institutional inefficiencies. Along with growing conflicts and security threats among offshore powers and weak economic cohesion and external dependence among regional states, these have acted to constrain ASEAN’s ability to fulfill its role as a unified actor in the international community and to further advance regional integration in Southeast Asia.

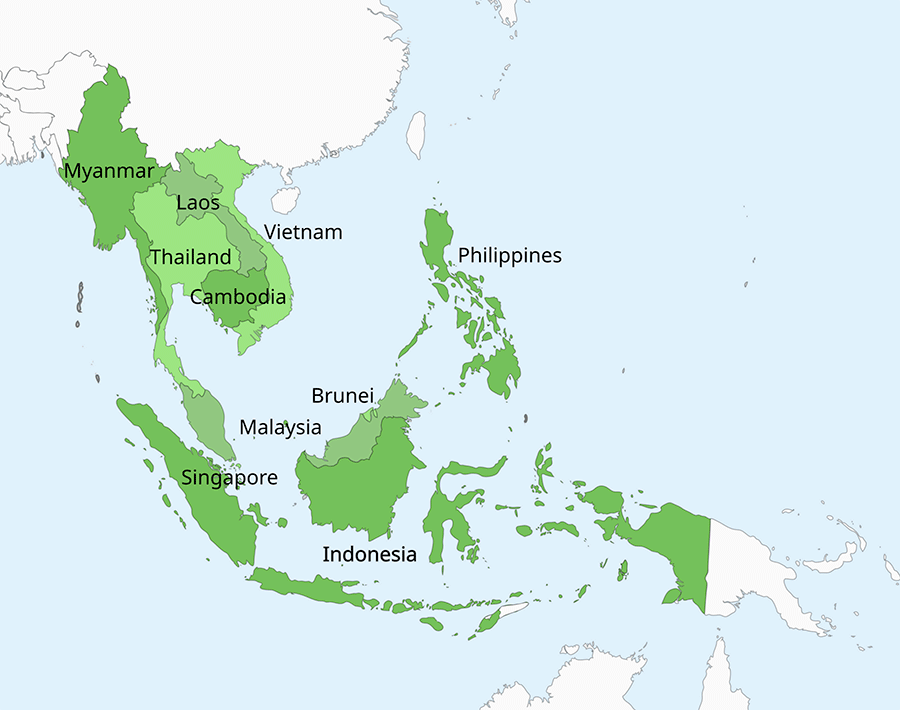

Fig. 1: Map showing the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). (Figure courtesy of Wikipedia Commons user Hariboneagle927, public domain)

ASEAN has demonstrated limitations and challenges in maintaining and applying its principles and methods, particularly in terms of security, economics, and human rights. There are rifts in the organization’s response to security issues, epitomized by the South China Sea dispute, and the issue of security conflicts among ASEAN countries remains. ASEAN does not want any offshore power to organize or lead multilateral security arrangements in Southeast Asia. However, it has yet to pursue a specific and unified foreign strategy toward these offshore powers, with member states adopting diplomatic strategies such as individual hedging instead. Despite the growing economic importance of Southeast Asia and the pursuit of regional economic cooperation through the signing of free trade agreements, the fragmentation of economic structures among the region’s countries persists. Differences in political systems, ranging from democracy to authoritarianism, and disagreements over how to approach human rights issues, coupled with the ongoing US-China conflict, have also exposed the problem of regional fragmentation. These factors have come to constrain regional stability and integration, making it difficult for ASEAN to effectively engage with external actors, and they have also contributed to internal divisions. Such limitations must be overcome if Southeast Asia’s regionalism, led by ASEAN, is to advance to a higher level.

Kyong Jun CHOI, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Political Science and International Relations, Konkuk University. Email: kjpol@konkuk.ac.kr.