Redefining gender identities on campus

<p>Exploring the transformative role of the university space for young women in India.</p>

Few women in India ever experience living on their own. In most cases, they shift directly from their natal home to their husband’s home; in both homes their lives are greatly monitored in terms of who they interact with, where they go, what they wear, and so on. This controlled movement and behaviour, coupled with disparate gendered norms and closely knit family and community networks, restricts women in exploring their own aspirations. However, in the last few years, the Indian subcontinent has seen a significant increase in the number of women enrolled in higher education. 1 In addition to enriching their scholastic knowledge, academic (and campus) life also has the potential to bring about a transformation in their social lives.

My research focused on young women who migrated from smaller towns - characterized by deeply asymmetrical gendered relations - to a seemingly ‘egalitarian’ and ‘metropolitan’ university space in the capital city of New Delhi, India. I explored the transformative role of the university space, emphasizing its significance in the learning as well as unlearning of gendered performances, and at the same time researched the pivotal role that the family ‘back home’ plays in this process. I argue that in migrating from semi-urban settings to a metropolis, women interpret, filter and absorb notions and performances of gender that differ from the ones they knew and make some of these part of their own social repertoire. The women experience not merely a physical shift but a situational shift, across contexts. They now have the freedom to explore and engage with social environments on their own terms; to internalize and build on these terms of engagement; and also to decide how much, if at all, they wish to change.

The research location

The Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) gated campus in New Delhi is spread across approximately 1000 acres of land; a large number of students, faculty members and administrative staff live inside its boundaries, making it easy for varied interactions to occur. JNU is especially known for its gender-sensitive admissions policy that gives extra weightage to female students and students from ‘backward’ groups/regions, as well as its minimal fees and many grant opportunities, which facilitate the enrolment of students from diverse socio-economic backgrounds.

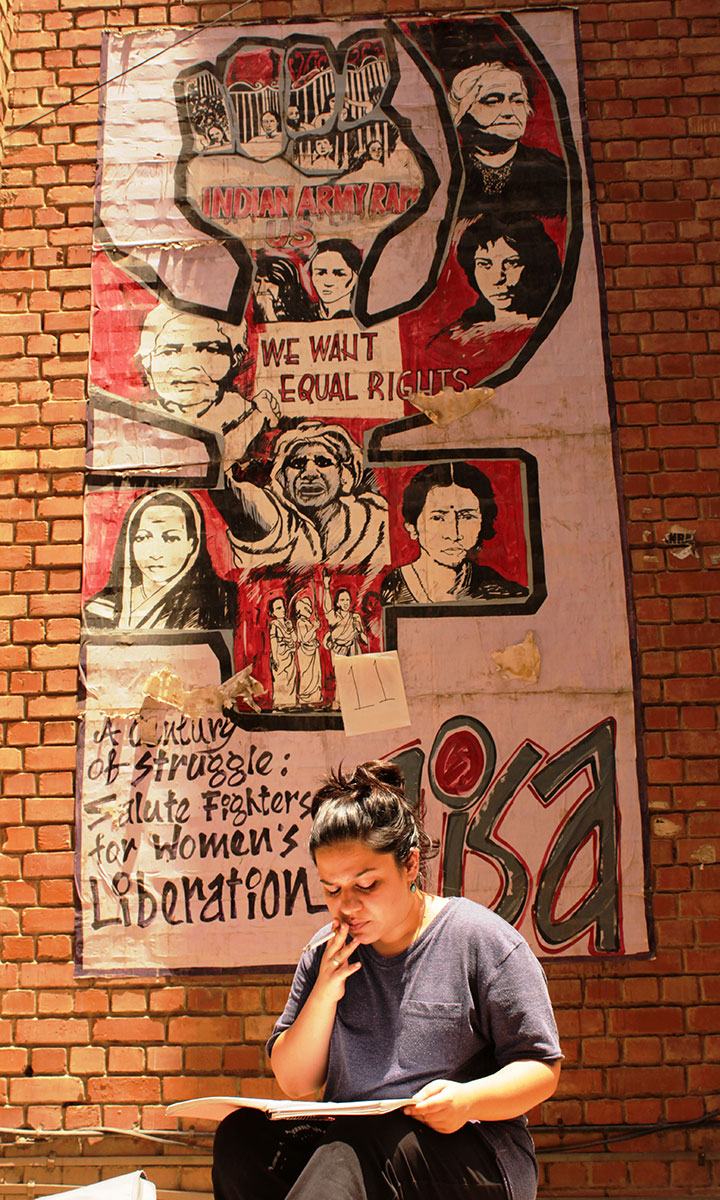

During my research at the university, I spent time with young women who came from very diverse regions of the country (Assam, Rajasthan, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand to name a few). Although their homes differed geographically, the restrictions they experienced in their social settings and relationships corresponded almost perfectly. Their previous education, often in the form of an all-girls convent school (run by nuns), had focussed on their ‘moral’ education. While young men are commonly expected to become leaders, confident and decisive, girls are supposed to grow into ‘good’, obedient, proper and demure women. They are often disciplined, at school as well as at home, about how to sit ‘properly’, to wear ‘decent’ clothes, and not raise their voices. Such gendered norms are, however, situational and contextual, and thus I explored them among women in a ‘new’ space; a space in which many popular practices may lend themselves to the creation of different norms. For instance, at JNU, it is common to see women actively participate in student politics, requiring them to be opinionated and vociferous during protests or debates.

Moving to JNU, as recollected by many of my respondents, involved getting lost in the campus, getting used to living independently, meeting people from diverse backgrounds, adapting to different habits, and people with different views of the world around them. Many spoke of a sense of freedom, free from prying eyes of relatives or neighbours. My interest lay in the new ‘ways of being’ that could potentially emerge in such spaces characterized by heterogeneity and anonymity.

Safety and freedom to experiment

“JNU is like an island”, was a phrase I heard in almost every conversation I had about the university. JNU enforces no restrictions on behaviour, dress code, hostel curfews, etc. 2 Another feature of this ‘island’ is the sense of safety, very much helped by the presence of a robust Gender Sensitisation Committee against Sexual Harassment (GSCASH). “Unlike ‘outside’ in Delhi, here in JNU the difference is that individuals (irrespective of their gender) can speak out and report the harassment that they face, and know that their matter will be looked into fairly”, stated one of my respondents Ritika. Many students remarked that they knew they would be heard and that someone would stand up for them if something were to happen. “You will always find me outside, roaming about in JNU... It’s so exciting to live in a place where I can roam around at any time”, exclaimed Shefali. The freedom to roam whenever and wherever they wanted was very new for all the young women. A historically left-leaning political atmosphere is what some believe to be the reason for this sense of camaraderie, which also extends into freedom of speech and opinion: students are encouraged to raise questions in their classrooms and to take part in public debates and discussions held on campus.

This completely new setting of JNU offers a space where women have the opportunity to freely and safely experiment. However, the question arises whether the students, especially the young women, are open to transgress the norms they have inculcated thus far, and even if they do, to what extent? What are their learning trajectories from this experience in the new space? Do they question their earlier ideals or denounce these new ways? What happens when they go back home for visits?

Maintaining and pushing boundaries

One of the processes I clearly witnessed was the blurring of strongly held ideas of what is good/bad or right/wrong. A few new students at JNU exclaimed with surprise, “some women here smoke as well!” As one of my older respondents told me, “you can recognize a new student by their reaction to a woman lighting up a cigarette.” This, she pointed out, changes over time and the students come to realize that the freedom they enjoy at JNU also means that it is up to them to decide what they think is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. Almost ashamedly, Marjauna (from Mangaldoi, Assam) recalled that when she was in her hometown, she believed that girls who wore short skirts or dresses were not ‘nice’ and did so only for attention from men. She told me that after coming to JNU she witnessed a different narrative – one that said it was okay to wear whatever one chooses – this made her question her earlier beliefs. She was excited to tell me that she had worn a dress for the cultural night in her hostel, and was happy to try this, though she still prefers jeans.

Women are allowed into the men’s hostels at JNU. This access gives women an opportunity to discover yet more new spaces, in turn also allowing them to discover new ways of interacting with, becoming comfortable among, and connecting to their peers. However, this allowance elicited many varied opinions. While all the women I spoke to found this access to a new space a liberating feature, some seemed sceptical and commented with “I don‘t think it is necessary that women are allowed to stay all night, they could have the rule till 11pm or something”, providing an interesting insight into the internalized notions of keeping distance from men, and perhaps reflecting the influences from home that (continue to) guide their thoughts and practices.

When talking about the absence of strict rules governing their lives at JNU, many of the women pointed out that they were glad that they came from a ‘small town’, ‘middle-class family’, telling me that they knew their ‘limits’ and wouldn’t want to breach their parents' trust. Although a lot of them have indeed tried many new experiences at the university (such as their first alcoholic drink, or first time being outside after 8-9pm) these are things they don’t see as ‘for them’.

The physical and contextual shift of moving from small town India to the cosmopolitan campus of JNU constitutes a tricky and extremely personal path, which each individual who experiences such a new space (that gives everyone the scope to change) grapples with. My respondents were well aware of the contradictions between their home setting and JNU. Many were comfortable living an almost dual life and switching between the two spaces. For instance, one of my respondents was not allowed to wear sleeveless clothes at home, but felt free to do so at JNU; every time she went home for a visit she would make sure to bring along the appropriate attire. However, there were a few women who felt the need to push the boundaries, some even drastically. One of my respondents was determined that she would not marry someone chosen for her by her family, even if it meant that she had to be alone and pay her own way. She had in fact already begun saving money from the fellowship that she received in order to fulfil this idea of hers. These were individual choices each one of the young women made, based perhaps on an assessment of the risks of making such choices, and their own ability or need to push boundaries.

Constant reinvention

Although I looked at the specific site of JNU, similar experiences play out across South Asia as more young women are gaining the opportunity to shift out of their homes in search of jobs and educational opportunities – opening up possibilities of new conversations. It is important to recognize the constant reinvention that these young women undertake while constructing themselves as women. Entrenched in their familial ties, these young women redefine their identities as they engage with ambivalent images, and simultaneously strategically transform themselves while developing their own aspirations.

Tarini J. Shipurkar was the winner of the 2016 IIAS National Master's Thesis Prize in Asian Studies. She wrote her thesis, entitled ‘Gender on Campus: Redefining Gender Identities at Jawaharlal Nehru University’, at the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, Leiden University (tarinishipurkar@gmail.com).