Reconstructing Relationships between Heritage Sites and Present-Day Communities through “Art and Archaeology”

Archaeological and cultural heritage can play an integral role in community-building, provided that outreach is socially inclusive. Reconstructions must represent diverse perspectives, and this is where collaborations between artists and scholars can provide extra value. Artist Sahoko Aki, who has made countless archaeological reconstruction illustrations, 1 and archaeologist Ilona Bausch2 share a passion for Japanese archaeological heritage. They are involved in “Art and Archaeology” projects in Japan, 3 where a team of archaeologists and artists collaborate with local communities and heritage specialists to engage in new ways with their cultural heritage, and try to include people who were not previously involved. In what follows, Bausch interviews Aki about such ongoing work, exploring themes of heritage, archaeological representation, artistic reproduction, and the importance of making participation in heritage as accessible and inclusive as possible, for example including local residents, people with disabilities, and children.

Reconstructing Jōmon

Ilona Bausch (IB): The prehistoric Jōmon in Japan (c. 14,000-500 BCE), 4 a complex culture of hunter-gatherers who also practiced horticulture, plays a central role in our work. Nowadays, the Sannai-Maruyama site in Aomori [Figs. 2-3] is one of the most famous archaeological sites in Japan, and part of the UNESCO World Heritage “Jōmon prehistoric sites in Northern Japan.” 5 However, before its discovery in 1995 (and its vigorous promotion in the Japanese media!), there was not so much public interest in the Jōmon period, except among archaeologists. As an artist, were you always interested in archaeology? How did you become involved in archaeological reconstructions?

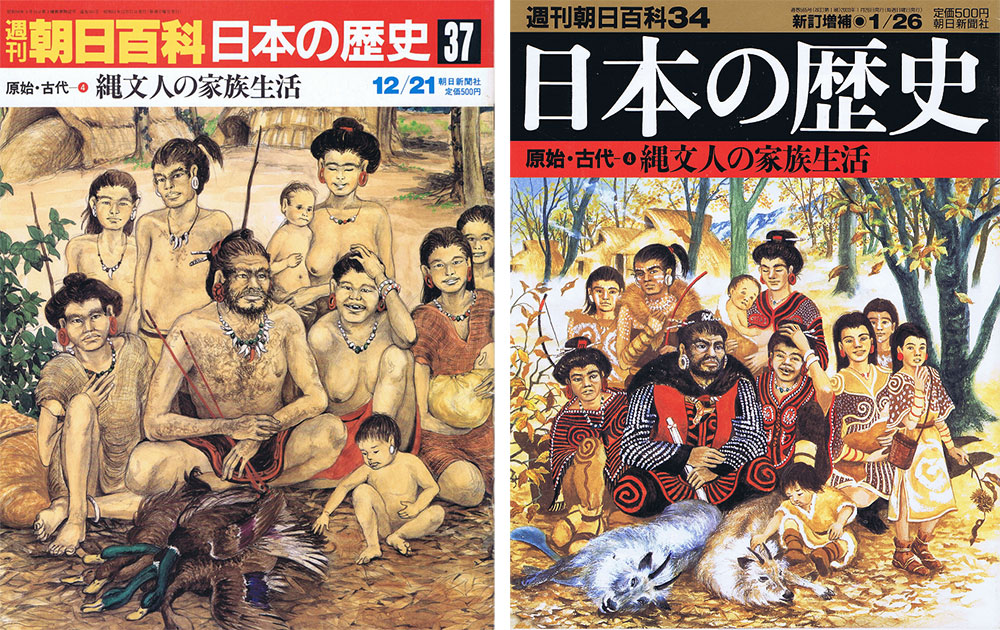

Sahoko Aki (SA): Originally, I had no intention to concentrate on archaeological reconstructions at all, until 1985 when I met Shūzō Koyama (1930-2022). As an archaeologist and cultural anthropologist at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, he wanted to demonstrate that Jōmon culture was far more complex than what other researchers in Japan considered at that time, so he was searching for an artist who could visualise his ideas about this Japanese stone age hunter-gatherer culture. Koyama was a researcher of indigenous cultures, who had carried out fieldwork among contemporary hunter-gatherers such as Australian Aboriginals. He introduced me to archaeological artefacts such as a Jōmon clay earspool decorated with red lacquer [Fig. 1], and its sophisticated design really drew me in. Our fieldwork interpreting archaeological artefacts in contemporary Japan inspired me to draw scenes from prehistoric people’s everyday life. My first published collaboration with Koyama “Family life of the Jōmon” [Fig. 1a] was published in 1986, and when the same magazine re-published this issue 18 years later in 2003, Koyama and I changed the cover, to represent the Jōmon people as more elaborately dressed [Fig. 1b].

Figures 1a-b: The change in perception of Jōmon complexity over time. 1a is the first collaboration between Sahoko Aki and Shūzō Koyama in 1986; 1b the re-issue in 2003. (Paintings by Sahoko Aki, in The Asahi Encyclopaedia of Japanese History)

IB: How have the insights and reconstructions changed over time, with the increasing public interest in prehistoric culture, and with changing socio-economic conditions?

SA: Archaeological research focus and its reconstruction images tend to reflect the interest of society at any given time. Thanks to the land development during the Bubble Economy boom in Japan in the 1980s, the researchers and the public alike were excited by the archaeological discoveries of spectacular large-scale settlements, with large prosperous populations, and increasing cultural and social complexity. For example, this can be seen in my commissioned reconstructions for the Sannai-Maruyama site in Aomori [Figs. 2-3] in the 1990s. The mural in Figure 2 represents an overview of the site. For Figure 3, I was asked to show the large population. This picture does not represent the everyday life or population size at Sannai-Maruyama, but a special festival where a large crowd is gathering together for a euphoric celebration.

Fig. 3: Reconstruction of a festival at the Sannai-Maruyama site. (Painting by Sahoko Aki, in collaboration with S. Koyama, 1996. Published in Quarterly Magazine Obayashi No. 42.)

But in the past 30 years, society’s interest and focus have changed globally. This also influences archaeological interpretations. Due to growing concerns about climate change and environmental disaster in Japan, the focus has shifted to representing small-scale settlements that coexist in harmony with nature. An example of this is Figure 4: the reconstruction of the Fudōdō site, a coastal Jōmon settlement in Asahi, Toyama prefecture from 5000 years ago, which is contemporary to the Sannai-Maruyama site. The contrast is very clear: the focus is on the environment. Even recent reconstructions of Sannai-Maruyama reflect this emphasis on surrounding landscape now.

Collaborating with scholars

IB: You explained that your commissioned reconstructions strongly reflect the interpretations of the archaeologists whom you work with. What is your work process, how do you create your illustrations in collaboration with archaeologists and other scholars?

SA: Usually, the researchers first invite me to the excavation site, to explain their own vision based on discovered evidence and data. Visiting the site is essential to understand the reason why the Jōmon people chose to settle at that place. To some extent, the site links horizontally with the modern landscape, because landscape features such as mountains, forests, rivers, and seas that were part of the ancient landscape still exist, especially in rural areas. Importantly, present-day local people are still relating to, and using, this landscape. By being there, you feel a strong connection to both the ancient population and lifestyle, as well as to the present one.

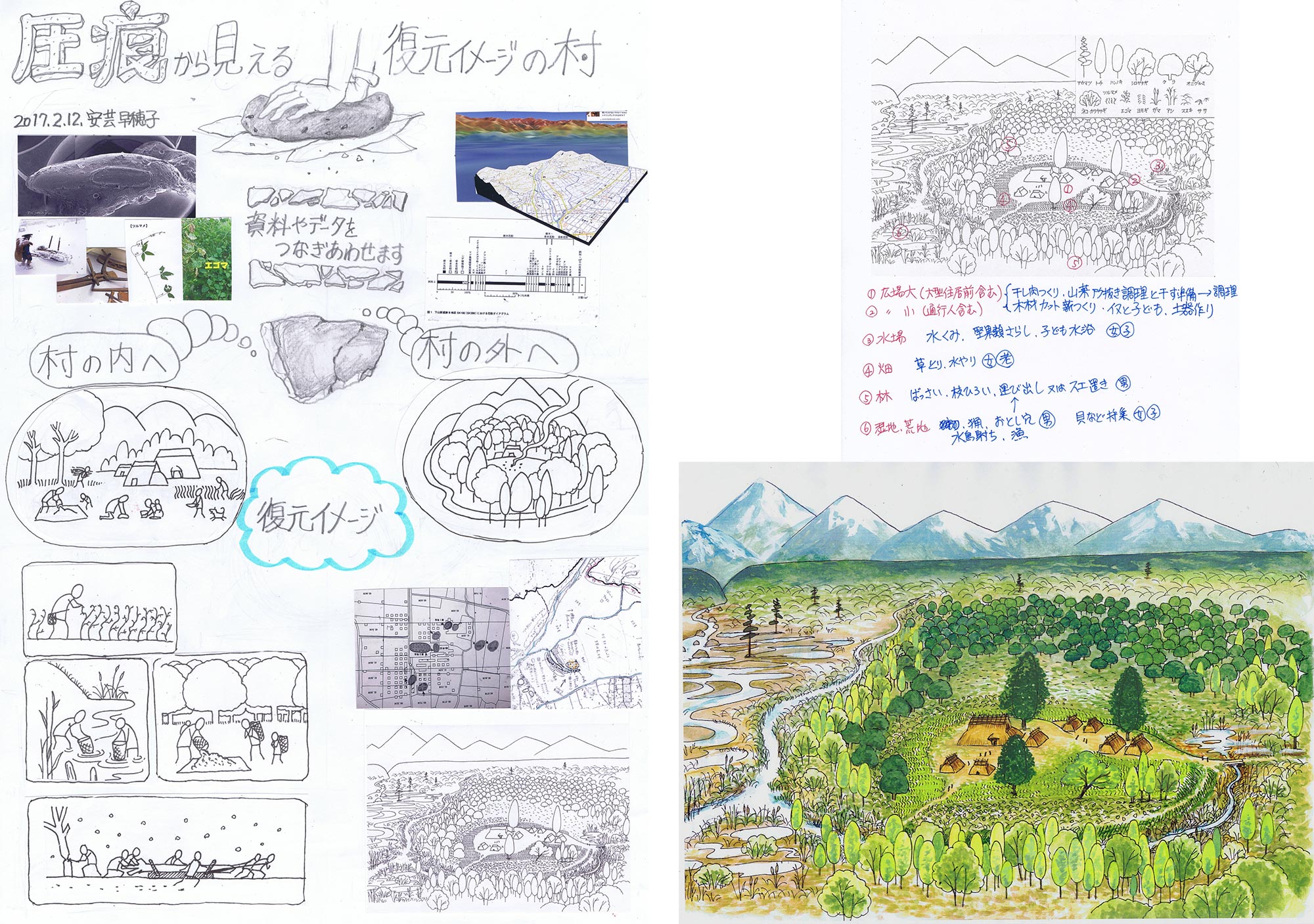

In order to create the Fudōdō landscape reconstruction shown in Figure 4, the entire process took over three months. Figures 5a-c show my various steps of conceptualising the reconstruction, based on the information I received from the local scholars. For this reconstruction, the main focus was the settlement within the wider landscape, and the way that Jōmon people used their natural environment. In this case, the archaeologist Noriko Kawabata, curator at the Archaeology and Folklore Museum in Asahimachi, Toyama prefecture, studied the tiny imprints that plant seeds left behind in clay pots after the pots were fired. Such data allow the reconstruction of the flora and the cultivated plants in or nearby the settlement. The geoscientist Takashi Kubo provided me with images of the wider landscape at the background of the site, based on his geological research. In this way, I received information on both the micro- and macro-scale. Working with geologists has given me a much wider perspective for my reconstructions.

Fig. 4: A reconstruction of the Fudōdō site in Toyama, from 2017. Currently, the sustainable relationship between humans and nature is at the forefront of perceptions of prehistoric life. (Painting by Sahoko Aki, 2017. Commissioned by Executive Committee of the Project to Rediscover the National Historic Site of Fudōdō)

IB: That reminds me of our first meeting at the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN) in Kyoto, as members of the interdisciplinary project “Neolithisation and Modernisation: Landscape History on East Asian Inland Seas” (NEOMAP). 6 I asked you to draw an illustration of a shamaness wearing jade ornaments for my research on prehistoric jade objects, and that was the start of our own long-term collaboration.

SA: Yes, I remember! I was stimulated by your idea that jade was not just used as commodity for economic exchange or for simple accessories, but also as amulets for spiritual protection of Jōmon people, their families, and their communities. Female archaeologists like you and Kawabata bring a different, more social-oriented archaeological perspective. In fact, I am inspired by all my encounters and collaborations with scholars, artists, and local communities. For example, the World Archaeological Congress (WAC) is concerned with the role of heritage in society. My activities with WAC gave me the invaluable insight that contemporary archaeology must also make an impact on present-day society.

Fig. 5a-c: Several stages in conceptualising the reconstruction of the Fudōdō site in Figure 4, based on information from an archaeologist and a geologist. (Sketches by Sahoko Aki, 2017)

Artistic perceptions and the importance of listening to diverse voices

IB: As an artist, you have a very different perspective from archaeologists or other scholars. In your opinion, why are collaborations between art and archaeology so important? What important insights can artists contribute?

SA: I see myself as being in the position of “interpreter” between archaeology and the public. First, where researchers are fact-based and logical, artists usually have a very different way of perception and expression. Artists have finely tuned intuitions, a kind of ‘antenna’ for understanding the contemporary societal issues and the transforming atmosphere of the era. Second, they also have a strong understanding of physicality, and of making sense of the world through the five senses, not just sight or words. Third, they are able to express these impressions through art. Art is action! Moreover, art does not require an absolute answer, which is important to reflect the diversity of the people’s perspectives in modern society. I think diversity is important in making reconstructions, because over thirty years I have witnessed how diverse not only academic arguments but also different social interests and impressions are, and how they change over time. Archaeological reconstructions – especially for prehistoric eras with limited information available – have to be built depending on whose image or interpretation it is. It reflects different views; it cannot be just one absolute “truth”. Unlike many archaeologists, I have come to think that present-day people can enjoy some freedom in their own image of the past, based on their own experience or impression, and artists have their own unique vision and ‘antenna’.

Art and archaeology collaborative projects can turn this freedom into a benefit for both archaeology and the public. The sensitive contemporary expression generated by close collaboration between archaeologists and artists can assist in bridging the gaps, between not only academics and the public, but also between different communities, like different generations, cultural backgrounds, etc.

IB: Why is it so important to involve local people in heritage projects?

SA: Diversity of people’s impressions and experiences is very important. That is why I also work with and listen to diverse groups, such as local residents, children, and people with impairments. The formation of the archaeological site landscape is continuous from thousands of years ago to now. I think it is important to listen carefully to the individual memories and experiences of contemporary people, and then to incorporate these in the reconstructions if relevant. Histories are usually recorded by authorities, but many of the archaeological artefacts represent the lives of unknown ordinary people. If archaeological site management and reconstruction is only done by archaeologists, you’d lack the diverse perspectives of the lived experiences of present local residents. They often have lived and worked in this environment and landscape for many generations. Their experiences quite likely contain some aspects taken over from their local ancestors. These real physical experiences make reconstructions vivid; you cannot get such insights from museum visits.

Sharing inspiration with children

IB: You have also been teaching arts and crafts to children, mostly ranging from kindergarten to primary school (roughly four to ten years old). Why, in your opinion, is art education so essential in society today? And how have your interactions with children influenced your ideas?

SA: Globally, today’s societies have so many problems caused by “difference.” Gaps of politics, culture, region, nation, generation, gender, and social class are becoming so complex. I believe one essential role of art is helping different communities in the process of finding a way to encounter each other and start bridging these gaps. For example, Osaka International School of Kwanseigakuin (Minoh city, Osaka prefecture), which has students from diverse backgrounds, annually invite me to teach about archaeology or cultural heritages. In contrast to many Japanese schools (which must conform to government-based annual schedules, edging art education out of the “essential studies”), their curriculum has a “social art” programme, giving their students extraordinary opportunity to be inspired by current global social and scientific problems and express them in their artwork. This approach is more meaningful for understanding the social role of art. Furthermore, it stimulates children’s individual creativity and imagination, which is very important for developing their cognitive and expressive skills, critical thinking, and confidence.

We have also been using art and archaeology workshops to make heritage accessible and understandable to children. Children have a naturally high energy and curiosity. Especially for urban children, there is a strong need to go outside and physically experience the natural environment. Whenever possible, I take the children to archaeological sites as well as museums. There they can also explore the production, use, and abandonment of artefacts within their original context and natural environment, rather than only experiencing static museum displays. For example, during our children’s excursion to the Fudōdō site in 2018 in Toyama prefecture, the children explored the archaeological site and the nearby mountain to find a clay source [Fig. 6a]. According to local archaeological research, Jōmon people may have used this same clay source for their ceramics.

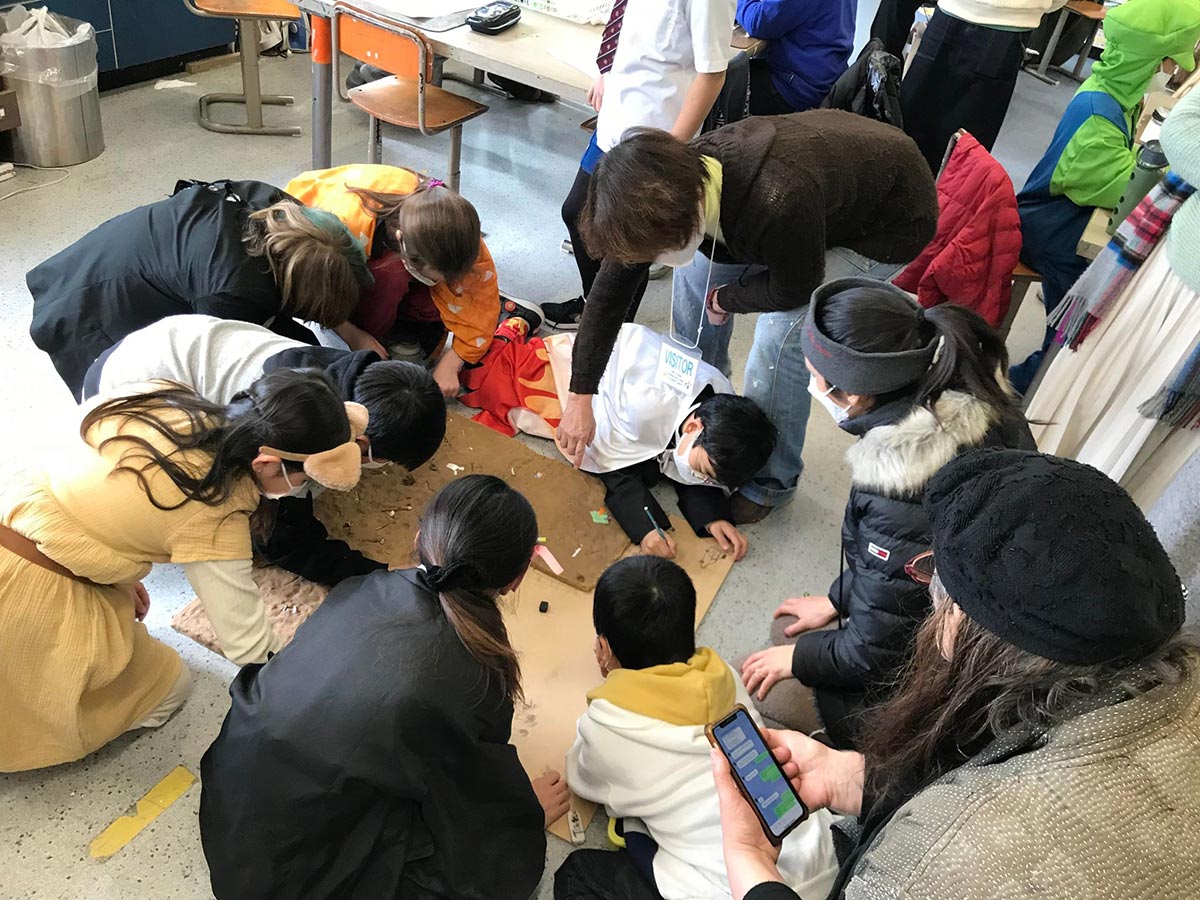

We also examine the vertical formation of cultural landscapes through time: how can the artefacts discovered in underground layers show us the lives of people in the past? For a project in 2021, we asked the children to imagine what 23rd-century archaeologists might discover when excavating a site from the 21st century. The children chose present-day materials such as plastic, metals, and modern garbage, to insert into the clay panel that mimics the soil layers of the excavation [Fig. 6b]. I enjoy working with children because their manner of exploration is very physical. They do not have the vocabulary or preconceptions that adults have, so they come up with very original and free ideas.

Fig. 6a: Children from Osaka International School on excursion camp at the Fudōdō site in Toyama, exploring the environment including potential clay sources. (Photo by Sahoko Aki, 2018)

Fig. 6b: At Osaka International School of Kwanseigakuin, Aki (brown jumper) and the students design the clay layers of a 21st-century archaeological site, inserting items that 23rd-century archaeologists might find: lots of plastic. (Photo by Jennifer Henbest Calvillo, 2021)

The role of heritage in resilience and community (re)-building

IB: You also became involved in several heritage projects throughout Japan, collaborating with archaeologists and local communities to increase awareness of the local heritage through “art and archaeology” projects, and to explore regional revitalisation. A particularly poignant example is the Power of the Invisible project, which focuses on the Urajiri Shell Mound site in Minamisōma, Fukushima prefecture. This region suffered greatly in the Great East Japan Disaster of 11 March 2011. 7 In the aftermath of the devastating earthquake and tsunami, here the disaster was compounded by the meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power plant. The entire town had to be evacuated for five years because of the radiation risks, causing the displaced community to scatter across the country.You encountered the local heritage manager Tsuyoshi Kawata in 2017 and started this collaborative project, where a team consisting of international archaeologists, heritage specialists, artists, and local residents are exploring the role of tangible and intangible heritage in community (re)building. A special “Focus” section about disaster, resilience, heritage conservation, and community-building (planned for The Newsletter in 2026) aims to present their experience and diverse perspectives. But meanwhile, can you tell us a bit more about your experiences?

SA: For example, Fudōdō in Toyama is quite a typical heritage site in a rural area, where the local community still has a strong link with their cultural and archaeological heritage, because the landscape has not changed that radically in 5000 years. But in Minamisōma in Fukushima prefecture, the entire modern landscape was destroyed, reverting to an almost prehistoric-like state. The rice paddies reverted into a marsh area. The local fishing village was destroyed. Only some houses, farms, and the Urajiri Shell mound Jōmon site located on hills were left safe. The traditional local landscape has irrevocably changed, with installations such as concrete wall reinforcements against the sea [Fig. 7].

Fig. 7: The post-disaster landscape at Minamisōma, Fukushima: visually impaired artists exploring the new "seascape" made of concrete. (Photo by Sahoko Aki, 2023)

Many people lost their homes; residents were uprooted after their five-year relocation. Tsuyoshi Kawata, who is responsible for the Urajiri site, also was in charge of saving the endangered local tangible and intangible heritage. 8 The local festivals and traditional crafts – for which the Minamisōma region is famous – are at risk of disappearing after the disaster. Because Urajiri Shell Mound already received the status of “National Historic Site” before the disaster, the site landscape is guaranteed to be preserved, and Urajiri has become a focal point for community-rebuilding activities. 9 At first, Kawata had concerns about the relevance of this prehistoric site for the Minamisōma residents. However, after the evacuation, Urajiri site became an indispensable meeting place for residents. Some of them can see their lost village land from there. Many local people have become personally invested in this site, taking care of it. The stone age shell mound has become their common preserved cultural heritage. 10 So much has been lost, but together with the local residents who returned, as well as the newly arrived residents, the project members are discovering the important role of diverse cultural heritages, tangible and intangible, and are learning and sharing the experience of the regional history. What really impressed me after working with them for eight years, is how their local heritage is helping the community with their recovery. Large-scale disasters can happen anywhere in the world, but perhaps the lesson from Minamisōma is that community memories with cultural heritage can play a powerful role in community (re)building, and ultimately in people’s recovery and resilience.

Inclusive accessibility to heritage

IB: The Urajiri site also featured in two “Art and Archaeology” initiatives to make museum exhibitions and heritage sites more accessible to people with disabilities, in particular visual impairment. You contributed an art installation to the tactile exhibition at the 2021 “Universal Museum” exhibition at the National Ethnology Museum in Osaka. 11 Furthermore, The Artist in Residence Project recently collaborated with two artists with visual disabilities to develop sensible accessibility for the Urajiri site. These projects and their outcomes are described in greater detail in our forthcoming article. 12 Could you briefly explain the purpose of your art installation at the tactile Universal Museum exhibition? And what did you learn from collaborating with the artists with visual disabilities?

SA: The “Universal Museum” exhibition, organised by Kōjirō Hirose (an anthropologist who had become blind at a young age), was based on principles of Universal Design, and aimed to stimulate visitors both with and without visual impairments. He started this project twenty years ago in an interdisciplinary research group, including artists like me and many with visual disabilities. Fumio Obara and Takaaki Kasugai were among them. For this exhibition Hirose asked me to make an artwork that would allow people with visual disabilities to “touch landscape.” 13 I decided to make a three-dimensional vertical cross-cut of the Urajiri Shell Mound landscape, to show how soil layers built up through time, and to make stratigraphy and site landscape formation understandable to everyone, including visually impaired people, and children [Fig. 8a]. People could touch the soil layers, the flora and fauna in the landscape, and the prehistoric tools such as digging sticks and axes [Fig. 8b].

Fig. 8a: “Tree on a Shell Mound” 3-D artwork in Osaka, made with acrylic paint, laser-cut wood, Japanese Washi paper, crushed shells, and clay. (Photo by Sahoko Aki, 2021).

Fig. 8b: Close-up: Children touching “Tree on a Shell Mound” painting at the tactile exhibition "Universal Museum" at the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku) in Osaka. (Photo by Sahoko Aki, 2021)

Related to this exhibit, the art and archaeology team also organised a special outdoor workshop for children to find their own digging sticks to decorate and use as a useful tool. To their excitement, Fumio Obara then spontaneously took the children on an adventure, navigating and exploring with the use of his stick. This experience of navigating the outdoors without using sight (using sound and touch) made a strong impact on the children.

We were impressed with Obara’s enthusiasm to research everything about the Urajiri site. He and Kasugai also were invited as Artists in Residence. Together with a team of local resident volunteers and heritage specialists, they participated in a multisensory exploration of the Urajiri site, its material culture, and its natural environment in October and November 2023. Obara was particularly keen to discover the tree in my art installation within Urajiri’s landscape. In February 2024, we had a project exhibition in Minamisōma to share the results of their fieldworks in artistic expression with the local residents. 14 Obara expressed the view of the Urajiri archaeological site without sight [Fig. 9]. Through tactile exploration, he is able to gather such vivid pieces of memories (on top of what he studied), and he processes these into a shape by woodcarving. His experiences are concentrated in his artwork, and people receive a powerful symbolic narrative. I respect and admire him, as it can be my ideal reconstruction.

Fig. 9: Fumio Obara and archaeologists exploring the landscape at Urajiri site in Minamisōma. (Photo by Sahoko Aki, 2023)

Reconstructed images can make an impact on contemporary society, when they reflect recognizable elements from life. “Art and Archaeology” practices invite people to enjoy the reconstruction images by including relatable experiences, on top of the factual archaeological data. Moreover, by including a diversity of perspectives, there is potential to reach more diverse communities. The vivid reality in the image grasps their attention, and people receive the symbolic message. These experiences are inspired by diverse voices and people who participated in our “Art and Archaeology” projects. 15

Sahoko AKI is an artist and a professional illustrator, and specializes in archaeological reconstructions in collaboration with researchers. She is involved in various cultural heritage projects in Japan aimed at accessibility diversification. She is an art educator for young children, and a cooperative research fellow at the Centre for Spatial Information Science (CSIS) at the University of Tokyo. Email: saho2213@gmail.com

Ilona BAUSCH explores prehistoric adornment, identity, society, and ritual, as well as contemporary heritage practices, in East Asia. She studied Japanese archaeology and cultural heritage at Leiden University, Durham University and Kokugakuin University (Tokyo), and has taught at Leiden University, and University of Tokyo. She currently teaches at Heidelberg University. Email: ilonabausch@gmail.com