Reconsidering the Notion of Sacrality for Chinese Buddhist Statues from the Second to the Sixth Century

It has long been understood that image worship was an intrinsic property and a distinctive practice of Buddhism. Consequently, it is widely believed that the arrival of Buddhism in China in the first century brought about the practice of worshipping Buddha images, which inaugurated the tradition of image worship in China. Recent research, however, challenges this belief. Studies by Kurt Behrendt (2004) and Minku Kim (2019) on India and Gandhāra suggest that the worship of Buddha images was not widely established until after 200 CE, so later than the first appearance of Buddha images in China. This raises doubt about whether Buddha images were viewed as legitimate icons of worship since their introduction in China, and whether their worship played a central role in the earliest stage of Chinese Buddhism.

Studies of Buddhist literature provide crucial insights for this investigation. The earliest Buddhist narratives foregrounded sutras in the transmission of Buddhism, while Buddha figures only became a crucial element in such narratives after the fourth century. Similarly, Eric Greene’s survey of anti- and pro-Buddhist apologetics demonstrates that image worship became represented as a prominent Buddhist practice only after the fifth century. 1 While Greene suggests that the newly developed attention to Buddhist image worship in polemical writings after the fifth century was entirely the result of historiographical construction, a review of archaeological evidence indicates this shift in Buddhist writings may not be altogether independent of changes in actual Buddhist practice.

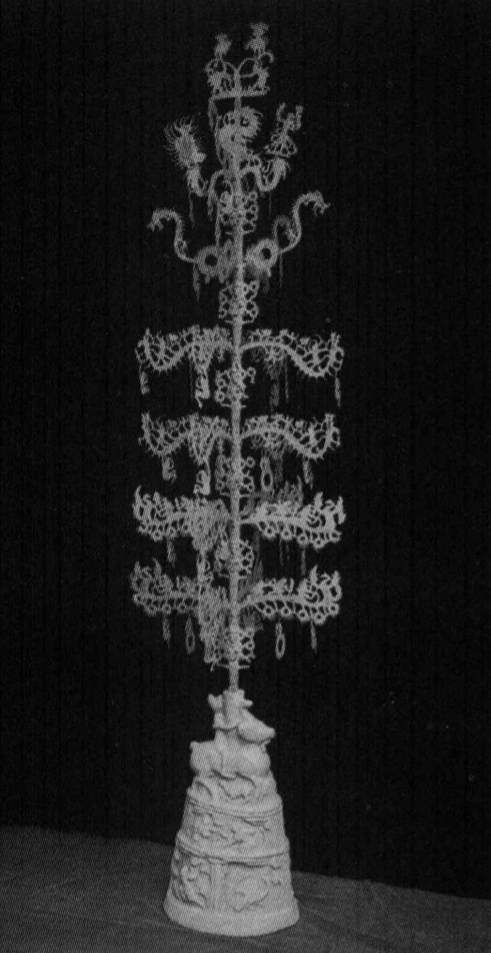

Indeed, the archaeological evidence points to a turning point around the fifth century, after which the activity of making and worshipping Buddha images suddenly flourished. Before then, only a modest number of Buddha images were found in a limited geographical range within China, and these were typically keyed to funerary or daily-use objects as decoration rather than used as independent icons of worship, as several scholars have pointed out. For instance, the majority of Han-period Buddha images were discovered in the southwestern region centered on Sichuan province, most of which were found on money-trees unearthed from funerary contexts [Fig. 1]. Buddha images are typically located on the trunk of the money-trees, while traditional Chinese auspicious motifs such as copper coins, the Queen Mother of the West, Taoist priests, dancers, divine beasts, and phoenixes adorn the branches and bases of the tree. Given the placement of the Buddha images, being visually obstructed by densely decorated branches spreading out horizontally, it can be inferred that the Buddha statues were not intended as objects of worship, but rather as one of the many decorative elements that enhance the money tree's symbolism of ascending to immortality or bringing good fortune.

Fig. 1. Money tree, Chongqing Guoyou Museum. From He Zhiguo, Yaoqianshu chubu yanjiu, Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe, 2007, p. 37.

In addition to their use on funerary objects, Buddha images have been found in the Yangtze region in the third and fourth centuries, but these were on objects used in ordinary life, such as mirrors, incense burners, wine and food vessels. Taking the example of the vessel [Fig. 2], which is a pan-shaped jar: it is decorated with three molded small Buddha figures at the widest part of the body. Moreover, the small Buddha figures are visibly slanted as they have been applied to the jar's curved surface. The casual manner in which the Buddha statues are attached, along with their inevitable exposure to contaminants during the vessel’s daily use, strongly suggests that these statues were considered merely auspicious decorative patterns rather than inviolable sacred images, as they were used to adorn secular utensils.

Fig. 2. Celadon jar. He Yunao et al. eds, Fojiao chuchuan nanfang zhi lu, Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 1993, Pl. 39.

However, the situation changed drastically after the fifth century. A sudden surge in the production of Buddha images swept across the Chinese territories. It was during this time that the Hexi region saw the beginning of the construction work of the earliest grottoes in China. The earliest cave of the Binglin-si Grottoes was excavated in the year 420 during the Western Qin, while excavations of other grottoes like Dunhuang, Jinta-si, and Tiantishan also commenced around similar periods. In 460 CE, under the auspices of the Northern Wei regime, construction of the Yungang Grottoes began in Pingcheng. Alongside these official projects, private sculptural making and patronage activities by common people also flourished.

Whereas only about 10 individual Buddhist statues dating back to the fourth century are known, over 120 statues from the fifth century alone have been identified. The number of statues dated between 500-580 CE on epigraphic ground exceeds 1500, and there are countless more Buddha statues without a precise date from the fifth and sixth centuries. Notably, during this prolific fifth-century period, Buddhist images no longer appeared as decorative images on secular objects. Whether it is sculptural steles, individual Buddha statues, or grotto sculptures, Buddhist statues only existed within sacred religious spaces, no longer mixed with secular life scenes depicted on objects like bronze mirrors, wine jars, or utilitarian jars.

The archaeological evidence therefore suggests a marked shift in attitudes towards making of Buddha images in actual practice around the fifth century. This change in practice most likely corresponded to, and was precipitated by, concurrent changes in the conception of Buddha images. While the early sutras maintain a utilitarian view of Buddha images – denying the presence of the spirit of the Buddha in the image (Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā, T224) – surveying donative inscriptions on Buddhist images allows us to observe how, beginning around the fourth and fifth centuries, Buddha images became identified with the Buddha himself. It is my contention that the heated discussion on the concept of dharmakāya in the intellectual milieu of Dark Learning (Xuanxue 玄学) of the Wei and Jin periods (220-420 CE) led to the understanding that Buddha images were worldly materializations of the abstruse body of the dharma. This homology between dharmakāya and Buddha images thus invested the latter with a divine character, which provided the crucial basis for the institutionalized practice of image worship in China.

Due to the limited length, this article cannot fully evaluate the influence of the discussion on dharmakāya on sculptural practices in China. However, it aims to propound a dynamic understanding of early Chinese perceptions of Buddha images. Worshipping Buddhist statuary was not necessarily central to the Buddhist praxis from the religion's initial phase in China. Nor was the establishment of Buddhist image worship in China necessarily the victory of foreign ideas, as commonly believed. Rather, it may have been based on the indigenous cultural understandings and interpretations of dharmakāya. Reconsidering these issues may contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the early spread of Buddhism in China, the influence of Buddhism on Chinese culture, and the interaction and blending of local and foreign cultures. This article serves as a starting point and looks forward to further discussions in this regard. 2 2021, no. 5, 64-74) of the same author.]

WU Hong is an assistant professor in the Department of Philosophy of Art and Art History at Fudan University. Email: Wu_hong@fudan.edu.cn