Recalling mass violence and the roads to reconciliation in Nanjing

A report on the 2017-KNAW-‘China Exchange Programme’-Summer-School

On 14 December 1937, the Japanese military captured Nanjing – then capital of the Republic of China – and the subsequent six-week long period of killing, raping and looting left a trail of devastation and destruction across the city. This period of extreme violence – also known as the rape of Nanjing – has left its mark on the city unto the present day. Yet, over the decades the memory-landscape of Nanjing has undergone considerable changes. In recent years there has been, for example, an increasing attention to the violent past; this is clearly visible in the public domain in the city. New museums (both state-supported and private) have been established, old museums have undergone thorough restructuring, and memorial sites have been increasingly institutionalized.

This increasing institutionalization does not automatically lead to an overall improved atmosphere for reconciliation. At least, that is the conclusion of an international group of participants of the Summer School ‘Practices of Remembrance beyond Memory Politics: Recalling Mass Violence and the Roads to Reconciliation in Asia and Europe’, founded by the China Exchange Programme of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences(KNAW). The Institute for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences (IAS), the Institute for Peace Studies at Nanjing University, and the NIOD Institute for War- Holocaust- and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam, organized this Summer School in Nanjing, which took place from 16 to 23 July 2017.

During the Summer School the participants – most of them students of peace studies or war studies – explored and discussed memory practices at historical sites of mass violence in Nanjing, it being a city where one of the major catastrophes of the Asia-Pacific War took place. They analysed how these sites relate to the past, to each other, to internal Chinese developments, and to foreign politics. Particularly relevant in this context is that in the pre-1976 political landscape, Chinese victimhood was not at the centre of attention; only in recent years has there seemed to be burgeoning consideration for the victims inside China. At the same time, part of Japanese society continues to play down or flat-out deny the atrocities committed. Even more complicating is that European attention to the Japanese atrocities generally focuses on the events directly following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The 26 participants of the Summer School came from China, Japan, Belgium and the Netherlands. On the first day the Dean of IAS, professor Zhou Xian, and the curator/director of Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, Zhang Jianjun, welcomed the group. Researchers from Nanjing University, professors Liu Cheng and Der-Ruey Yang, and professor Ribbens, dr. Eickhoff, dr. Futselaar and dr. Buchheim from NIOD delivered the lectures and supervised the analyses of the on-site visits. The faculty aimed to create a secure and productive space for fruitful deliberation. In order to facilitate a smooth interdisciplinary and intercultural collaboration, the group focused on developing a common language for their discussions. It proved crucial to develop sensitivity for the different perspectives and to analyse how the different viewpoints came into being, and how they changed over time.

The participants of the Summer School were divided into six multi-national groups; each of them was assigned one site in Nanjing. Four of these sites were official memorial sites, one was a private enterprise, and paradoxically one location played a role in the Nanjing Massacre and especially in its representations but is not an official memorial site. On the last day each group gave a 20-minute presentation, introducing the site and elaborating on its historical significance in the context of the Summer School.

In preparation for the final presentations, the groups paid visits to the sites, conducted field research, and built on the insights found in literature and lectures. They endeavoured to develop a better understanding of the potential tensions on location between institutionalized cultural memory (archives, museums, official commemorations, etc.) and communicative memory (based on individual, inter-generational exchange). Important questions in this context were: what do people actually do when visiting a site, which representations of the violent events are present at the sites, which narratives can we trace in them and what is their meaning, and which audiences are targeted, and by whom? Although taking different approaches, all of the groups conducted oral history interviews with the visitors and local citizens, looked at popular representations, analysed the inclusiveness/exclusiveness of the narratives, tracked the historical transformation of the sites and the interpretations of the Nanjing massacre, and examined the sites from the perspective of peace and reconciliation. Below, we summarize the most important findings of the groups.

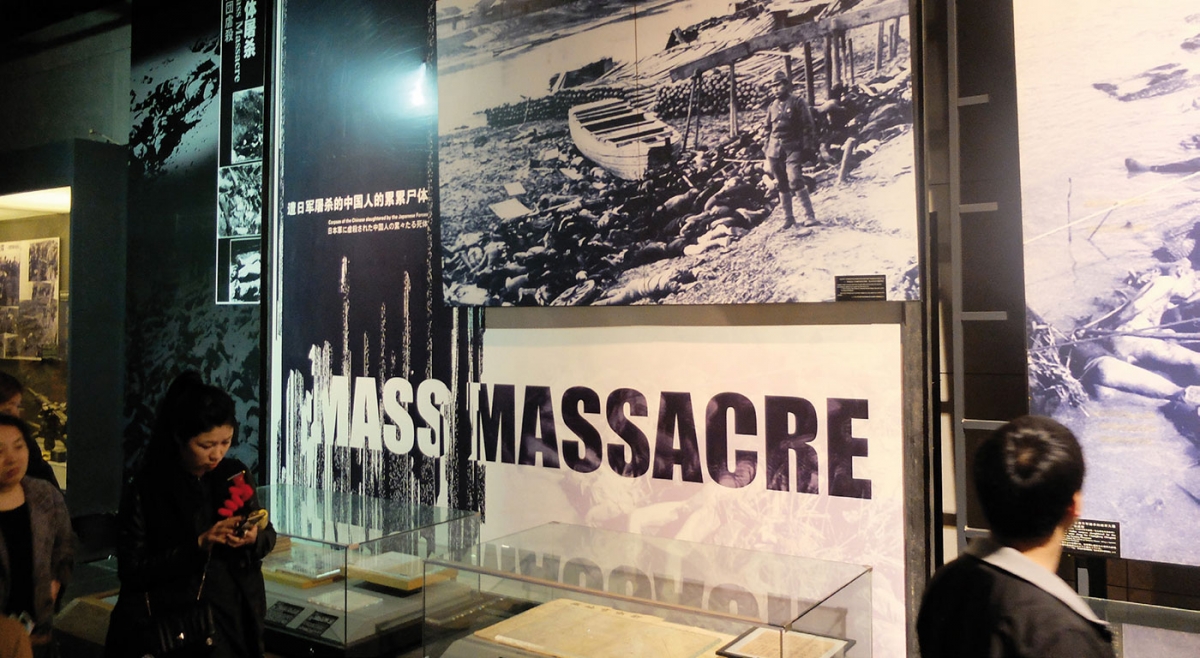

The Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall (NMMH)

Established in 1985 by the Nanjing municipal government, NMMH is the dominant site in Nanjing and abroad related to the memorialization and commemoration of the Nanjing massacre. The memorial is built on a former mass execution and burial site, and consists of three main parts: an exhibition hall with historical documents and objects; an outdoor exhibition area with multiple sculptures and memorials; and ‘The Mass Grave of 10.000 Corpses’ where preserved skeletal remains of the victims are displayed. At the time of our visit, the main exhibition hall was undergoing a renovation for the upcoming 80th anniversary of the massacre. We therefore visited the temporary exhibition about the Western witnesses of the massacre and their activities during the event.

The group presentation on NMMH stressed the significance of the massacre in the local, national and global memory cultures. They highlighted how the foundation of the museum and the memorialization of the massacre were closely related to political developments, especially in regard to the diplomatic tensions over the different interpretations of the history by China and Japan. The group noticed that the victims were represented as Chinese individuals, while the aggressors were framed as collective Japanese perpetrators. In addition, the analysis revealed how NMMH tries to integrate the Nanjing massacre into global cultural memories of WWII by mentioning the war in the European theatre and including personal testimonies of Western witnesses in abundance. The final part of the presentation covered the representation techniques used in the outdoor sculptures and physical structures, focusing on such aspects as static/dynamic displays and light environment. The group critically illustrated how memory cultures and politics at different levels affect the representations and commemorations of the massacre at NMMH.

The Presidential Palace

Located in downtown Nanjing, the Presidential Palace is a huge complex of historical buildings and gardens. The site has been a key location for China’s modern history. It was a residence of Sun Yat-sen, who became the interim president of the Republic of China in 1912. Fifteen years later, the Nationalist Government led by Chiang Kai-shek established its headquarters there. After the Nationalist Government fled to Taiwan in 1949, the palace was used as government offices. In 2003, the palace was opened as the Museum of Modern Chinese History.

The group presentation on the Presidential Place demonstrated how ‘Chinese identity’ was constructed and conveyed. In particular, they focused on the representation of the Republic of China era, and argued that the site presents China as a cultural unity and showcases its continuity, despite the political turmoil it has experienced. The group critically asserted that the history after 1937 is under-represented at the site. The central focus of the representations of the Republic of China is instead on Sun Yat-sen. Through their analysis of on-site statues (including Communist and foreign political figures), the group concluded that Sun Yat-sen is represented as a reconciliatory and unifying figure between mainland China and Taiwan, and beyond.

John Rabe and International Safety Zone Memorial Hall

This memorial hall is the former residence of John Rabe, who, as the director of Siemens Nanjing, sheltered more than 600 Chinese refugees during the Nanjing massacre. Fallen into oblivion for decades after the war, a German-Chinese joint initiative turned the residence into a museum in 2006. The museum focuses on the help that John Rabe and other members of the International Safety Zone gave to the citizens of Nanjing during 1937-1938.

The group analysed this site with three different lenses: commemoration, peace education and reconciliation. Although Rabe as a figure is remembered in China and Germany through different commemorative activities, the group found out that the local on-site commemorations take place sporadically and are conducted by neighbours, survivors, and small groups of people. However, the site is gaining popularity as a Chinese tourist destination, which might affect the future of commemoration there. In analysing the museum’s contents, the group sought to identify information they thought was missing. Their examination revealed that the museum concentrates on Rabe’s personal history and on contemporary German-Chinese relations, whereas historical information on the ‘bigger’ picture, such as the Sino-Japanese War, the Nanjing massacre, and the German-Japanese partnership is missing. The group further concluded that the museum does not contribute to inter-Asian reconciliation because its dominant theme is the German-Chinese relationship.

Nanjing Folk Anti-Japanese War Museum

Established in 2006 by the businessman Wu Xianbin, this museum is one of the two private museums in Nanjing dealing with the Nanjing massacre. As well as being a private museum open to the public, it functions as an archive and documentation centre, as the director has collected more than 5,700 objects. His staff has furthermore conducted oral history interviews with up to 1,000 veterans.

The group analysed the content of the museum, including the panels on the massacre, interviews, inscriptions on the wall, veterans’ handprints and other exhibited (military) objects. They extracted two main narratives: the national struggle and the honouring of veterans. The history of the massacre and the Sino-Japanese War were framed in themes of civilian victimhood and soldiers’ dedication. The group highlighted that the museum builds on a unique mixture of cultural and communicative memories. In one sense, it uses the same sources and pictures that are displayed in other museums, like the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, and follows a similar story line. At the same time, though, the museum actively incorporates oral history testimonies and objects from individual donators, building upon communicative memory. At the end, the group discussed the museum’s cooperation with civic associations in Hiroshima, and concluded that in a highly controversial and political event like the Nanjing massacre, it is easier to have reconciliation at the bottom-up, grassroots, civilian level, rather than on the official, top-down, state level.

Comfort Women Museum

The Comfort Women Museum is built in the barracks of a former Comfort Station in Nanjing. For decades after the war, the premises were left in decay, but in 2003 a former Korean comfort woman visited and identified the place. The museum opened in 2015, and comprises several buildings and exhibition areas. The main objects displayed are wartime objects used by the Japanese military and personal items of former comfort women they used after the war. One of the main themes of the museum is ‘tears’; visitors can spot ‘tears’ recurrently drawn and represented in sculptures, objects and architecture.

During the presentation, the group emphasized three main narratives constructed and expressed by the museum through the uses of displays and objects: systematic dehumanization and objectification by the Japanese military; suffering and innocence of victims and survivors; and the survivors’ struggle for recognition. The group argued that the museum embeds personal testimonies into institutionalized ‘big’ stories throughout the exhibition. Similar to the private museum, this museum thus builds upon both cultural and communicative memories. At the end of the presentation, the group talked about a sculpture titled ‘Endless Flow of Tears’. The sculpture represents a crying former comfort woman and visitors can actually wipe off water coming down from her eyes. The group discussed the different ways that this statue was perceived emotionally among the group members, shedding light on the various reactions and receptions of the visitors.

Zhongshan Gate

Located in the east of Nanjing, Zhongshan gate was one of the sites attacked, bombed and destroyed by the Japanese military during the early phase of the invasion of Nanjing in December 1937. Though restored as a ‘heritage of shame’ site after 1945, the gate is not included in the official memory landscape of Nanjing. No official memorial or commemoration takes place at the site. However, the gate is a recurrent theme in numerous representations of the Nanjing massacre. Using clips from films made both within and beyond China, the group convincingly illustrated that the gate is used as the symbol of Japanese invasion and cruelty, and on some occasions also as a symbol of Chinese resistance.

To further investigate the role of the gate in the current local memory culture, the group conducted 24 short interviews with Nanjing citizens. The interview results demonstrated the various levels of knowledge and understanding regarding the gate: some interviewees had not heard about the gate before, others emphasized the practical usages of the gate (bus station, entrance of a highway), whereas only one person associated it with the Battle of Nanjing. Based on these results, the group concluded that although the gate is prominently present in cultural memory, it is not part of local communicative memory.

Concluding remarks

The group presentations on different sites drew attention to a range of commemorative practices, messages and appropriations of history taking place in the memory landscape of Nanjing. We came to realize that there is a strong coherence between these sites, not only because they commemorate the same events, but especially because they make use of a common pool of sources. One example is the diaries by John Rabe, the German businessman who played a large role in the establishment of the international Nanjing Safety Zone. This source, originally in German, has been translated into Japanese, Chinese and English and is used at different sites. Rabe not only provides a meticulous description of the atrocities committed, he also describes what activities the members of the Nanjing Safety Zone executed and how they negotiated with the Japanese officials. In hindsight, his descriptions have become the basis of important (re)calculations of the numbers of victims and casualties.

Yet, we also realized, the recent growth in the production of cultural memory does not automatically lead to an overall improved atmosphere for reconciliation. The question of how to integrate the mass violence into local, national and global history remains contested. Contemporary Nanjing is, as a result, a site of conflicted history where disagreements about the past continue to pop up at both expected and unexpected moments.

Eveline Buchheim, researcher and coordinator at NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (e.buchheim@niod.knaw.nl);

Martijn Eickhoff, senior researcher at NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (m.eickhoff@niod.knaw.nl);

Aomi Mochida, MA student Radboud University Nijmegen, research intern at NIOD (amshg1w4us@gmail.com).