Pyongyang as a Crossroads for Afro-Asian Cooperation

Contrary to popular perceptions of North Korea as a hermit kingdom, its capital city used to be a hotspot for international travel. During the Cold War an eclectic mix of politicians, soldiers, journalists, and students travelled to Pyongyang for conferences, meetings, and training courses. Of particular importance was the stream of African visitors to North Korea, a largely overlooked but nonetheless important phenomenon in the history of the Global South. The connections that were forged between Africans and North Koreans were part of a larger framework of Afro-Asian cooperation that sought to change the global order.

While North Korea’s past was largely shaped by war, its future will be shaped through diplomacy. Following the end of Japanese occupation in 1945, the Korean peninsula was divided between the Soviet Union and the United States. In 1948, two separate governments were established, and from that moment on the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) were embroiled in a fierce struggle for legitimacy. Tensions between the two Koreas culminated when North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950. For three years, the peninsula was ravaged by terribly destructive violence, until an uneasy armistice commenced. The Korean War had a profound impact on North Korea, and in particular on Pyongyang.

A diplomatic hub

During the Korean War, Pyongyang was effectively razed to the ground, a human tragedy that simultaneously provided North Korea’s city planners a tabula rasa to construct an entirely new city. Pyongyang became a canvas for North Korea’s vision of a new society. 1 It embodied the impressive post-war reconstruction of the North Korean nation, which initially outperformed the rival South Korea in terms of economic growth. The city was more than a place where people lived; it was a platform for the performances of the North Korean theatre state. 2 Kim Il Sung (1912-1994) charted the country’s foreign policy through the adoption of Juche, an indigenous philosophy that emphasized North Korea’s independence from China and the Soviet Union. 3

Fig. 2: Kim Il Sung receives Samora Machel, 1971. (Still from the documentary President Kim Il Sung Met Foreign Heads of State and Prominent Figures April 1970-December 1975).

Through skilful diplomacy, North Korea became an important player in a rapidly decolonizing world. It was a time of turmoil and revolution, and politicians from Africa and Asia joined hands in an attempt to devise an alternative world order. 4 Pyongyang was a crucial node in the rapidly developing Afro-Asian world. The city hosted meetings of the Non-Aligned Movement and the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organisation, two organisations that embodied the rise of South-South cooperation. As such, Pyongyang became a crossroads of different cultures. Visitors from all over the world came to the capital and were impressed by its sights. Among them were many delegations from Africa.

Fig. 3: Zambian delegation in Pyongyang, 1987. (Photo from North Korean state media)

The African continent was crucial for North Korean foreign policy. Many recently independent governments or liberation movements fighting for freedom were receptive to Kim Il Sung’s anti-imperialist message. 5 A defected North Korean diplomat with working experience in Africa told me that Kim poured a lot of effort into understanding and navigating African affairs. 6 In order to establish fraternal relations, North Korea invested in cultural diplomacy. Examples are the translation of North Korean books and magazines into African languages, the dissemination of film and photographs, and travel opportunities. 7 As such, Pyongyang became a tool in Kim’s Africa policy. North Korea utilized an "invitation diplomacy" in which influential Africans were brought to Pyongyang to experience the wonders of Juche. 8 The city exemplified North Korea’s role as a model for the developing world. 9 To this end, African guests were treated to elaborate tours around the city, festive banquets, and other types of honours.

African presidential visits

The most high-profile African visitors to North Korea were political leaders. 10 Occasionally, African leaders were invited for specific conferences, for example workshops or summits from the Non-Aligned Movement or the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organisation. Most important, however, were bilateral invitations. Influential leaders from across the continent were encouraged to come and meet Kim Il Sung. North Korean diplomats even travelled to the former president Mobutu Sese Seko’s (1930-1997) holiday address in Belgium to hand-deliver an invitation, after they failed to reach him back home in Zaire. 11 African leaders were usually accompanied by large entourages of ministers, army leaders, and party officials. They often enjoyed these visits and returned several times. An example is Kenneth Kaunda (1924-2021), the president of Zambia, who visited Pyongyang multiple times in the 1980s. Kaunda appeared to be “an admirer of the North Korean system,” and Zambian officials were “genuinely impressed” by North Korea’s development. 12

Fig. 4: Kim Il Sung receives Robert Mugabe, 1993. (Photo from North Korean state media).

The meetings with Kim Il Sung were used to discuss political cooperation, cultural exchanges, and perhaps most importantly, military support. Kim offered training and weapons to several African liberation movements and governments. “I was taught how to load, unload, and clean weapons,” recalled Yoweri Museveni (b. 1944) in his autobiography about his first trip to North Korea in 1969. “It was the first time I had ever handled a weapon.” A few years later, Museveni overthrew the regime of Milton Obote (1925-2005) and became president of Uganda. He remains president today, and Uganda subsequently became a significant military ally of North Korea. This story illustrates the importance of the connections that were fostered in Pyongyang many years ago. Personal relations were developed into strong bilateral relations that proved to be profitable to both African and North Korean regimes. 13

Not only presidents travelled to Pyongyang; their children did as well. In 1979, the first president of Equatorial Guinea, Francisco Macías Nguema (1924-1979), sent his wife and children to North Korea. Shortly thereafter, Macías was deposed in a coup and executed. His family remained in Pyongyang, effectively living in exile under the guardianship of Kim Il Sung. This extraordinary story is described by Nguema’s daughter, Mónica, who left North Korea in 1994 and published two memoirs in Korean and English. 14 She was enrolled in military boarding school and became fluent in Korean. Among her friends were two other presidential children: the sons of Matthieu Kérékou (1933-2015), the president of Benin. A central theme in her memoirs is the environment of central Pyongyang, which shaped her experiences. Mónica describes daily life in the city centre, the awe-inspiring government buildings, dancing to the music of Madonna in a discotheque in central Pyongyang with diplomats, defected American soldiers, and other foreign students.

Learning the lessons of North Korea

Mónica Macías’ story is an rare insight into the lives of African students in Pyongyang, of which there were many. Aliou Niane, a Guinean student in North Korea between 1982-1987, revealed in an interview that he encountered students from Ethiopia, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mali, Tanzania, Togo, and Zambia. Niane arrived in North Korea after his president, Ahmed Sékou Touré (1922-1984), visited Kim Il Sung’s 70th birthday party in Pyongyang and was offered ten scholarships for promising Guinean youth. Niane was one of them. 15 Unfortunately, there seem to be very few memoirs or other egodocuments describing these experiences.

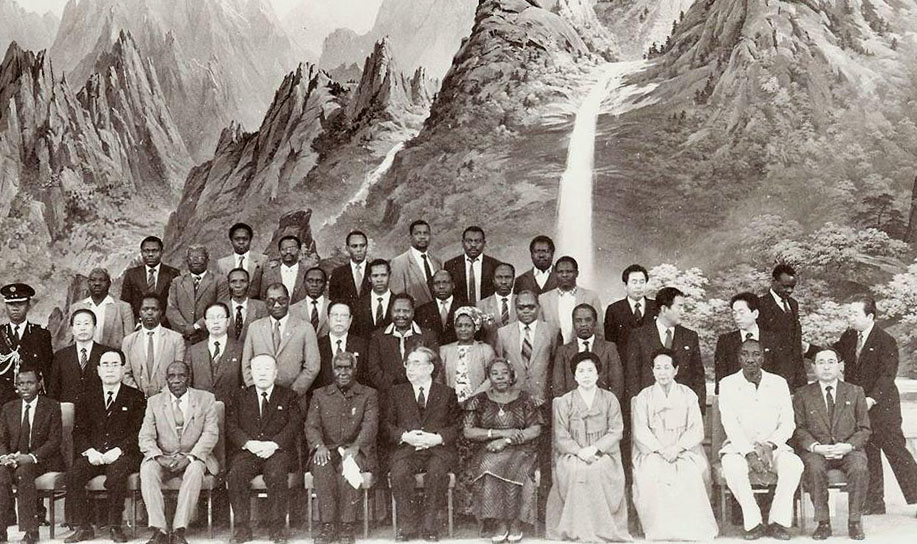

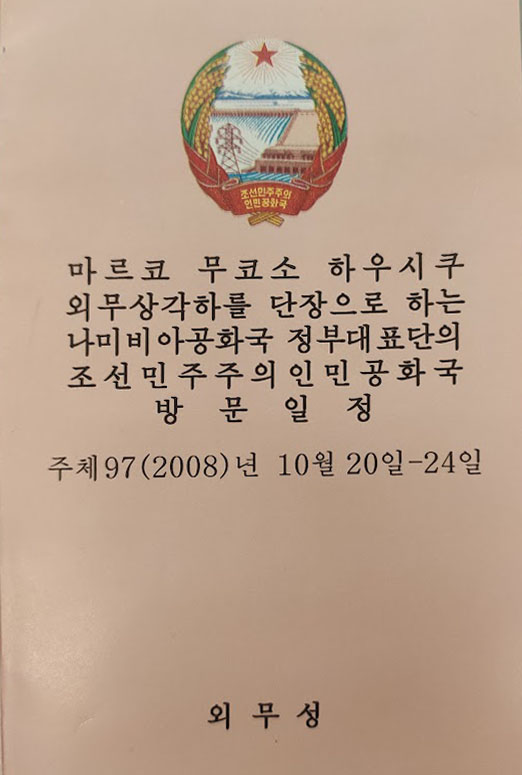

Fig. 5: North Korean program of a Namibian visit to Pyongyang, 2008. (Photo by the author, 2022)

By mere chance, I found a collection of North Korean journals in a Namibian archive that contain travel descriptions from African visitors in Pyongyang. The Study of the Juche Idea journal solicited travelogues from non-Korean authors across the world. Francisco Barreto, a member of the Guinea-Bissau-Korea Friendship Association, described the “soaring sky-high” Tower of the Juche Idea, a 170-metre high monument in Pyongyang. “I could hardly take my eyes from the sculpture.” Foreign visitors were always taken on tours around the city to inspect monuments, schools, hospitals, farms, and other places of interest in and around Pyongyang. “My heart stirred with boundless emotion and excitement,” wrote the Togolese philosopher Sossah Kounoutcho, “I was fascinated by the beauty of the city.” Kounoutcho also recollected seeing Francisco Macías Nguema, the president of Equatorial Guinea and father of Mónica.

Fig. 6: Namibian delegation in Pyongyang, 2008. (Original photo from North Korean state media, image made by author, 2022)

The authors of the Study of the Juche Idea went to Pyongyang to learn the lessons of Juche for their respective home countries. Oumar Kanoute, a party official from Mali, expressed awe at the reconstruction of North Korea after the destruction of the Korean War. This was an example to Mali, a country “also determined to build an independent national economy” whilst overcoming “obstacles and difficulties.” 16 The contributions to Study of the Juche Idea are full of praise of Pyongyang and its inhabitants. These articles are essentially hagiographies of Kim Il Sung and unfortunately contain little reflection on the real-life travel experiences of the authors.

Conclusion

When the Cold War came to an end, North Korea was plunged into a crisis. Economic mayhem, a large-scale famine, and the death of Kim Il Sung changed the North Korean state. It no longer had the funds to support its soft power programs in Africa. Rather than spending money, North Korea was fixated on earning money to ensure regime survival. As a consequence, the days of Pyongyang operating as a hub for Afro-Asian solidarity were over. Nevertheless, African-North Korean exchanges continued on a different path. Occasionally, news bulletins about African visitors in Pyongyang appear in North Korean state media. The focus of such exchanges is now, however, on the sale of North Korean arms, technology, and labour.

Popular perceptions of North Korea are influenced by myths and mysteries. One of the most persistent ideas is that of North Korea as a state that operates in isolation, cut-off from the rest of the world. While there is some truth to this statement – e.g., ordinary North Koreans cannot travel freely – it overlooks the importance of Pyongyang as a destination for African delegations, and as a meeting space for the non-aligned world. Whether informed by solidarity or pragmatism, or a combination of both, these exchanges challenge the widespread image of North Korea as a reclusive kingdom.

Tycho van der Hoog is an assistant professor at the Netherlands Defence Academy and a PhD candidate at the African Studies Centre of Leiden University. Email: t.a.van.der.hoog@asc.leidenuniv.nl