Promoting Nationhood by Urban Environmental Design: The Overlooked Filipino Architect-Planner, Antonio Toledo (1890-1972)

The disciplines of architectural history and planning history are littered with articles, papers, and books that focus upon ‘star practitioners.’ Yet, it is a well-known fact that the vast majority of buildings within urban settlements, and also the vast majority of town or city planning schemes, are designed by those not of high vocational standing. With regard to the practice of urban planning in the Philippines during the early 1900s, whilst much attention has been lavished upon Daniel Burnham (1846-1912) and his 1905 plans for Manila and Baguio, in actuality urban designing throughout the Philippine Archipelago was executed by William E. Parsons (1872-1939) and Filipinos such as Antonio Toledo (1890-1972). Still, in comparison to the volume of attention bestowed upon Burnham, little has been researched of Parsons, Toledo, and the like. Consequently, today, few details are known of their true impact upon the evolution of modern Philippine urbanism.

When analyzing the character of an urban planning system it is imperative to realize how its existence is grounded in particular decision-making processes. Therefore, when scrutinizing a planning system’s form it is imperative, first, to grasp the means by which decisions affecting the laying out of buildings, roads, and open spaces are fashioned. Second, it is vital to know what the networks of information, actors, and power are that contribute to the urban environment’s formation – and how. 1

In terms of the Philippines’ American colonial period (1898-1946), and in particular the short span of time within it known as the Commonwealth Era (1935-46), the local planning system was both designed and implemented by staff of the Bureau of Public Works’ (BPW) Division of Architecture (DoA).

The DoA’s activities were led by Filipinos from circa 1919. Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s – hence by the commencement of the Commonwealth Era, when Filipino-led decolonization was practised – with their activities expanding in volumes, DoA personnel were engaged in a substantial number of urban design schemes. For example, the Annual Report of the Secretary of Public Works and Communication (1937) remarked that requests for plans from municipal and provincial governments, combined with applications for plaza, street, and park projects, were substantially higher than what they had previously been. 2

Yet, notwithstanding such facts, the written history of the BPW during 1935 to 1946 is meagre. Owing to the lack of basic data on, for instance, architectural and planning activity during the Commonwealth Era, a number of basic questions remain unanswered: Did the character of urban design change after 1935 owing to the nature of governance shifting? Post-1935, who undertook urban planning activity? Considering the need to answer such questions, this paper focuses upon an individual greatly downplayed within the historiography of Philippine society.

Antonio Toledo: The underappreciated Filipino architect

Within the frames of Asian Studies and Philippine Studies, few scholars discuss/examine the career of Antonio Toledo. 3 Even within inquiries of Philippine architectural development, Toledo’s name is typically written about in a manner secondary to that of Juan Arellano (1888-1960). As a case in point, the historiography of the American colonial-era presents Arellano as the innovator of local aesthetics, and, in accord, Toledo is merely presented as a supporting actor. This paper, to be blunt, challenges that standpoint. Utilizing findings from a monograph published in 2023,4 this paper will explain that it was Toledo, not Arellano, who was central to the activities of the DoA during the Commonwealth Era.

In terms of context, two matters must be recognized when exploring the career of Toledo during the 1930s and 1940s. On one hand, it is necessary to appreciate what the Commonwealth Era was, and what it meant to the Filipinos who lived during it. On the other hand, it is crucial to realize that Toledo was hands-on when it came to facilitating urban betterment and beautification in Manila and other Philippine places. In the case of improving the quality of the built fabric in Manila, The Philippine Free Press noted in 1938 that efforts were being made to supply the capital city with “better drainage, wider thoroughfares, more bridges across the Pasig River, cleaner esteros [estuarine inlets], and a healthier atmosphere.” 5

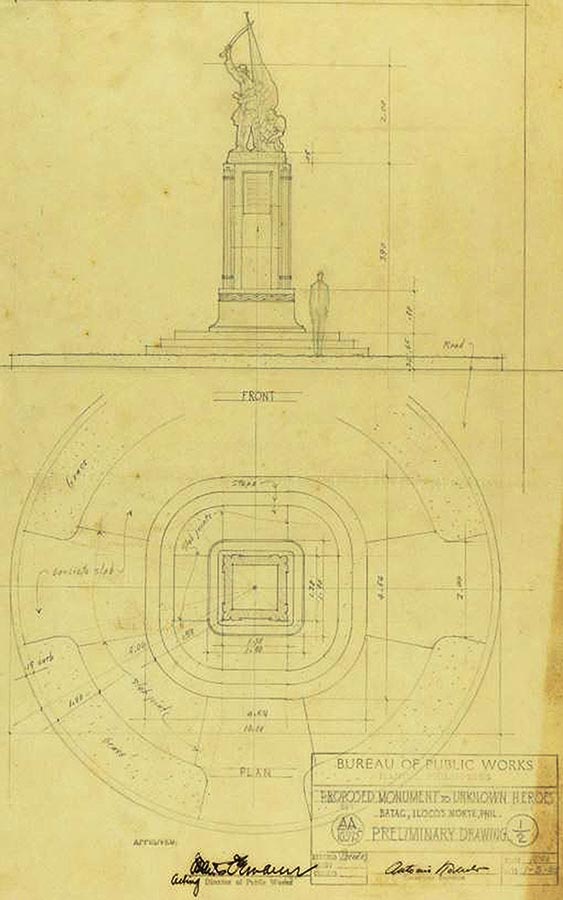

As someone responsible for designing road schemes, park layouts, plaza designs, and monuments, as earlier indicated, Toledo’s professional influence went beyond the boundaries of the Philippines’ capital city. In 1940, for instance, in Batac (Ilocos Norte), he proposed a more than six-metre-tall Monument to Unknown Heroes [Fig. 1], and, in keeping with the nationwide tradition started by the Americans during the early 20th century, he designed monuments dedicated to national hero José Rizal (1861–96).

Fig. 1: The preliminary drawing by Antonio Toledo for the Monument of Unknown Heroes. (Image courtesy of the Archives of the Bureau of Public Works)

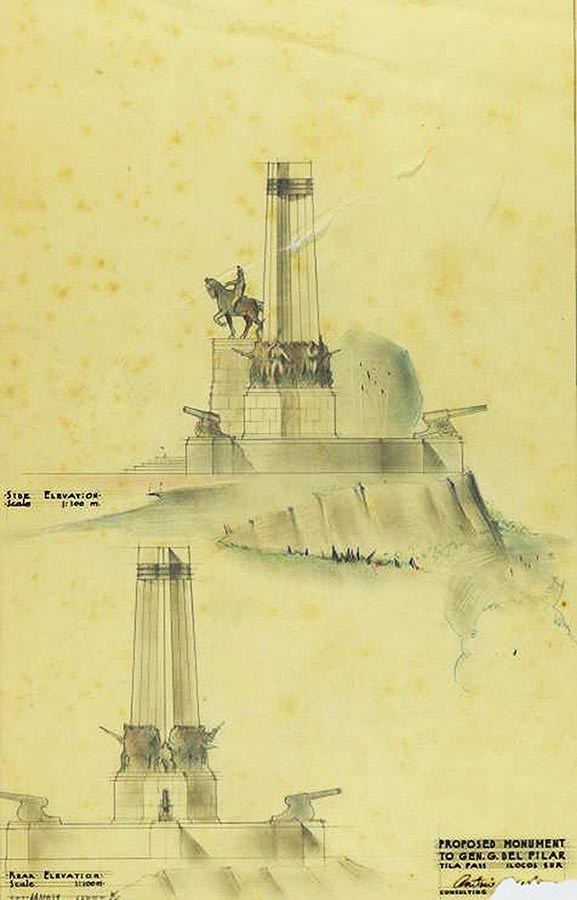

He also proposed the Gregorio del Pilar Monument. To be erected at the Tila Pass in Ilocos Sur – the site of the Battle of Tirad Pass, which took place on December 2 1899 as part of the Philippine-American War – this new artistic feature sought to honour a hero of the Revolutionary Army and, more broadly, demonstrate respect to all Filipinos who had supported the late-1800s quest for national independence [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2: Toledo’s 1939 Monument to General Gregorio del Pilar. (Image courtesy of the Archives of the Bureau of Public Works)

The Commonwealth Era, the new state, and planning

In broad terms, the colonial history of the Philippines is divided into two parts. The first part relates to the Spanish age (1565-1898). Succeeding the Spanish-American War of 1898, the second part is the American period. It officially ended with the granting of Philippine independence in July 1946. However, during the time when the United States colonized the Philippine Islands, a number of notable cultural, legal, and political evolutionary phases transpired. One such advancement took place in mid-November 1935. At that time the Commonwealth, a Filipino-run administration described as “for and by the people,” was established. 6 It was purposefully set up to prepare the country for impending self-rule. 7

As the final chapter of the United States’ colonial rule in the Philippine Archipelago – and, in conjunction, a new highpoint in the decolonization process kick-started during the first decade of the 20th century by the Filipinization of the colonial bureaucracy – the Commonwealth’s creation was a political means to an end. It was, said its President, Manuel Quezon (1878-1944), a governmental instrument “placed in our hands to prepare ourselves fully for the responsibilities of complete independence” [Fig. 3]. 8

Fig. 3: A Commonwealth Era sketch by Guillermo Tolentino, exhibited at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Manila, representing the political independence soon to be given to Filipinos by the Americans. (Photo by the author, 2023)

From 1935 the Commonwealth Government readily encouraged social progress: the welfare, happiness, and civil liberties of the public were keenly promoted by Quezon’s administration. Stirred by the composing of a new constitution in early-1935, the public were given unprecedented support in their physical, mental, and social advancement. 9 Moreover, the Commonwealth Era saw urban planning activity within the nation’s more than 900 municipalities. As the Secretary of the Interior, Elpidio Quirino (1890-1956), outlined: “I advocated the policy of town planning not only to encourage the growth of civic pride in each locality but to also to stimulate them to pursue the policy of self-sufficiency.” 10

Toledo and his support of Commonwealth Era progress

The Filipino state’s ambition after 1935 to uplift the physical and social character of urban communities, and so augment liveability, was an extension of environmental rationality introduced by the Americans at the start of the 20th century. Following Daniel Burnham’s recommendations in 1905, new roadways, public edifices, and green spaces were laid out in Manila. But, to reiterate prior remarks, even though Toledo designed a range of projects during the 1920s and early 1930s, in written history he is habitually spoken of in terms of playing a secondary role to his DoA colleague, Juan Arellano [Fig. 4].

Such presentation of Toledo, and of Philippine urban design history in general, can be attributed to the grand narrative writing style established by Winand Klassen in the mid-1980s. 11 Klassen, and those subsequently writing in a similar vein, have tended to heap praise upon Arellano’s career yet, at the same time, have downplayed Toledo’s vocational accomplishments. As a result, much has been overlooked of what Toledo did to reshape the character of the Philippine urban form in the years preceding national independence.

By way of illustration, Toledo designed numerous road schemes, park projects, and prominent public edifices in Manila. In March and October 1939, he tendered proposals to revamp Dewey Boulevard. Today known as Roxas Boulevard, Toledo sought to incorporate green spaces and walkways alongside the roadway originally envisaged by Daniel Burnham as the capital city’s ‘Ocean Boulevard.’

Arguably his most ambitious roadway proposal – put forward in February 1940, and completely ignored within the grand narratives of Philippine urbanism – was a 50-meter-wide ‘Proposed Circumferential Road Around Manila, Philippines.’ Comprising a monumental parkway, the scheme came to act as the precursor for the orbital roadways suggested in 1945 by Louis Croft in his General Report of Major Thoroughfares – i.e., the thoroughfares deemed vital to the post-World War Two redevelopment of Manila and vicinity. That roadway, today known as EDSA, acts as a major suburban thoroughfare and, given its heavy use, is renowned as one of the most congested traffic arteries in Metro Manila.

Aside from designing new roads and revamping existing ones, in order to boost accessibility between different districts in Manila, Toledo devised schemes to reshape road junctions. Furthermore, as noted above, he designed new green spaces within a capital city rapidly enlarging and densifying.

In August 1939, he composed a layout for Harrison Park (originally known as Malate Park). Seeking to change what was essentially a swamp into a new recreational hub, his park project incorporated a lagoon, winding pathways, and a bandstand. Prior to this, in May 1938, he composed a park alongside Calle Leveriza and Calle Indiana in the southern suburb of Pasay. With a symmetrical arrangement of lawns, pergolas, trees, and hedges, all organized from the centrally-positioned fountain, the Calle Leveriza Park’s layout illustrated Toledo’s expertise in the art of civic design. Such skills were further evident in downtown architectural schemes, such as for the City Hall and the Agriculture and Commerce Building sited in proximity to Manila’s principal green space, Rizal Park.

The four-storey City Hall, completed in 1941, on Padre Burgos Avenue was the largest of Toledo’s Commonwealth Era buildings in the Philippines’ largest city. Integrating a domed clock tower measuring almost 100 feet in height, the City Hall’s enormous neo-classical bulk brought a new scale to the central cityscape. Sitting within an unencumbered site of almost 12,000 square meters area, the north-south oriented structure, once completed, formed an ‘architectural wall’ along one of Manila’s primary inner city thoroughfares [Fig. 5].

Fig. 5: A view along Padre Burgos Avenue towards the west-facing elevation of the City Hall. (Photo by the author, 2024)

Even though architectural critics during the time of the City Hall’s construction alleged that the edifice was visually dowdy, it is often overlooked by scholars today that in September 1938 Administrative Order (AO) No. 78 was issued and Commonwealth Act No. 393 was passed. With Section 1 of the decree permitting the construction of a Commonwealth Triumphal Arch, the proposed structure – sited near the Legislative Building and City Hall – was to memorialize the inauguration of the Commonwealth, 12 and would have greatly elevated the visual character of Padre Burgos Avenue had it been completed prior to Imperial Japan’s invasion and subsequent occupation.

To cost ₱500,000, the Commonwealth Triumphal Arch was designed by the ‘conservative classicist’ 13 Guillermo Tolentino (1890–1976) to resemble a singkaban (festival arch). The concrete structure – 27 metres high, 22 meters wide – was to be decorated with bronze figurines depicting historical native heroes as well as persons representing the present and future Filipino generations [Fig. 6].

Fig. 6: A scale model of Tolentino’s Commonwealth Arch, held at the National Museum of Fine Arts. (Photo by the author, 2023)

Although largely unknown today, the Arch was not Tolentino’s first venture to venerate the Commonwealth’s existence: in late 1937, to honour the second anniversary of the Commonwealth’s founding, and to celebrate the government’s promotion of social virtues, an array of sculptures – titled “Equality before the Law,” “Labor,” etc. – were erected at the downtown seafront space known as Luneta. These monuments, along with the Arch and various BPW projects undertaken before 1941 by Toledo, collectively informed Filipinos of political exertions underway to ‘elevate’ their nation’s future.

With Manila’s built environment reshaped after 1935 to help “knock the country back into shape,” 14 new public buildings, public spaces, and monuments were intentionally sited so as to be accessible and visible. Such practice evolved the City Beautiful model of urban planning imported to Southeast Asia by Burnham, one that from 1905 to 1935 symbolized (at least to the Americans) the values of modernity and democracy.

However, post-1935, the built environment was once more employed as a tool of the state, although now it was to articulate the values of Filipino unity and democracy – as largely personalized by President Quezon. 15 Only through the promotion of such values, he believed, could the Philippines secure its future. 16 Such rationale, exposes how key actors (e.g., Toledo, Tolentino, etc.) molded the bond between symbolic struggle and the unfolding political vision of ‘a new city’ in which Filipino structures and spaces, physically and figuratively, could be constructed.

Ian Morley is Vice Chair (External) of the Department of History at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.