Power of Poetry in a King’s Court

Throughout the history of Iran, the kings of various dynasties had poets in their service to compose poems in their praise, recite poems, or in some cases, sing for them. We have evidence of the presence of minstrels as early as the time of the Arsacids (247 BCE. - 224 CE.) known as gosans. They were not only musicians and singers, but also poets whose traditions found their way to the court of the Sasanians (224-651). 1 Poetry did not die after the Islamic conquest of Iran in 651; rather it returned even more powerfully. Before long, the art of poetry became an essential subject for those who pursued knowledge at the time. Any learned man, if not a poet himself, was required to know the art of poetry and the great poets to some extent. Persian historical sources since the 9th century demonstrated a strong connection between prose and poetry by including verses in their texts. Therefore, in this short article, I will look at two historical sources which made use of poetry in order to answer an important question about this artform and its role: What does poetry bring to the table that makes it so desirable for the ruling class?

Poetry and history in the service of the Seljuqs (1040-1194)

It is not easy to put a label on the career of Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Sulaymān al-Rāvandī; he was perhaps what we call today a “Jack of all trades”. According to the introduction of his book, Rāḥat al-Ṣudūr va Āyat al-Surūr, 2 Hereafter RṢ. he was from a village called Rāvand, in the vicinity of Kashan (south of Tehran). His family was famous in the field of calligraphy, and he learned this skill throughout his years of study as well. He writes about this in his book, saying that he could write in 70 different calligraphic styles along with bookbinding, gilding, and illumination. 3 His education was not limited to calligraphy, he also learned about history, poetry, and religion. One of his uncles, Zayn al-Dīn, who was particularly well-known for his calligraphic skills, was summoned by Sultan Ṭughril III (r.1176-1194) to the court of the Seljuqs to teach the Sultan the ways and secrets of calligraphy. As an apprentice to his uncle, Rāvandī was introduced to the court of the Sultan where he assisted his uncle in various calligraphic and book production projects.

Unfortunately for Rāvandī, Ṭughril III proved to be the last of the Seljuq Sultans and he was defeated by the Khvārazmshāhids in battle in 1194. Having lost his patron, after a period of frustration and disappointment, Rāvandī wrote a history of the Seljuqs and decided to offer it to Sultan Kaykhusraw I of the Rum Seljuqs (1192-1196/1205-1211), a branch of the Seljuq house ruling over Anatolia.

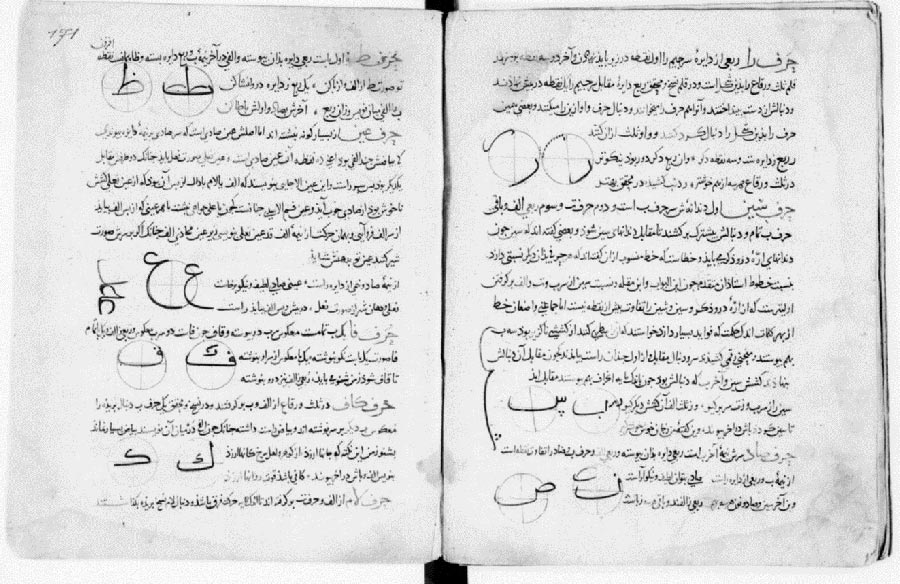

Like the author himself, it is difficult to put his book in a single category. Although RṢ narrates the history of the Seljuq dynasty, it also includes chapters on calligraphy [Fig.2], hunting, drinking, and shooting; the subjects which are mostly in the domain of boon companions (nadīm). A nadīm was supposed to keep company with kings and when necessary, advise them on various matters.

Fig. 2: Instruction on drawing letters in calligraphy in Rāḥat al-Ṣudūr.

Apart from the arts of a nadīm, Rāvandī demonstrates his talent in poetry by including 2680 Persian verses in his book. Out of these 2680 verses, 654 were composed by Firdawsī and selected from various sections of Firdawsī’s book, the Shāhnāma (the Book of Kings). The Shāhnāma was a long poem composed by Firdawsī in 1010 which narrates the story of Iranian people from the mythical era until the Islamic conquest of Iran. The Shāhnāma was received well in later periods to such a degree that other poets not only wrote poetry imitating the style of the Shāhnāma, but also copied the Shāhnāma; Sometimes the illustrated and gilded versions were produced by the order of kings. The Shāhnāma left an enormous impact on various aspects of Iranian history, particularly on literature.

As giving advice was considered one of the responsibilities of a nadīm, RṢ is replete with such topics, especially about how to rule with justice. Precisely at the beginning of the book, Rāvandī sets ancient Iranian kings as examples of just rulership for his patron, Sultan Kaykhusraw. In his introduction, after paying homage to the Sultan, he introduces Firaydūn, a mythical king in the Shāhnāma as an example of just rulership:

ز مشک و ز عنبر سرشته نبود

فریدون فرخ فرشته نبود

4 تو داد و دهش کن فریدون تویی

بداد و دهش یافت این فرهی

“The auspicious Firaydūn was not an angel, he was not made of deer musk and ambergris. He became fortunate by doing justice, if you do the same, you are also a Firaydūn.”

Along with the above example which makes an explicit connection between Rāvandī’s patron and the kings of the Shāhnāma, Rāvandī applies a different type of allegory as well. With the help of this device, Rāvandī attracts the attention of his reader to the scenes of the Shāhnāma implicitly:

5 نگشتی سپهر برین از برم

نزادی مرا کاشکی مادرم

“I wish my mother did not give birth to me; I wish I was never born.”

Here two situations are compared: the first in the Shāhnāma relates the story of a battle between Iranian forces and those of their enemies, the Turanians. The verse is said by an Iranian hero, Gūdarz, who is concerned about the aftermath of the battle. The second case, in the RṢ, is in the story of Sultan Ṭughril III, Rāvandī’s first patron, where the opponents of the Sultan hear of his arrival; They were, as the verse states, terrified, ‘wishing they had not been born’.

Rāḥat al-Ṣudūr contains ample references to the Shāhnāma, either explicitly connecting the Seljuqs to the ancient Iranian kings, or implicitly by applying the scenery of the Shāhnāma to Seljuq history. Although Rāvandi was among the first authors who made use of the Shāhnāma in this way and on such a massive scale, he was not the last one. In the following section, we will see how an Ikhanid historian also turned his attention to the Shāhnāma.

Poetry and history in the service of the Ilkhanids (1256-1335)

Khvāja Rashīd al-Dīn Fażl Allāh Hamadānī was a prominent historian and a vizier in the service of the Ilkhanid dynasty. He came from a family of physicians in Hamadān and before his appointment as vizier, he had practiced the family occupation. It was during the reign of the second Ilkhan, Abaqa (r.1265-1282) that he started to climb the ladder of power until he was appointed as the vizier during the reigns of two Ilkhanid Sultans, Ghazan (r.1295-1304) and Öljeitü (r.1304-1316). Ghazan ordered Rashīd al-Dīn, as the ruler’s trusted vizier, to write a history of Chinggis Khan and his descendants [Fig.1]. The book, however, was only completed after the death of Ghazan and Rashīd al-Dīn decided to offer it to Sultan Öljeitü, Ghazan’s brother and successor. The book, called Tārīkh-i Mubārak-i Ghāzānī 6 (the Blessed History of Ghazan) was well received by the Sultan. He commanded Rashīd al-Dīn to add two other volumes, one on world history and another on geography which, together were called the Jāmiʿ al-Tavārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles).

Rashīd al-Dīn’s first volume, TMG, has 159 verses composed by 17 different poets. 7 Firdawsī, with 24 verses, is the poet whose poems have been applied the most in TMG. Like RṢ, we can see a clear effort to connect Rashīd al-Dīn’s stories to those of the Shāhnāma. However, in this case, the heroes of the Shāhnāma are the primary focus:

8 همی رای شمشیر و تیر آمدش

هنوز از دهن بوی شیر آمدش

“Even with the smell of milk still on his breath, his thoughts raced to the sword and arrow.”

The original verse in the Shāhnāma belongs to the story of Rustam, the most famous hero of the Shāhnāma, and another hero, Suhrāb. Suhrāb is well-known in the Shāhnāma due to his early maturity and physical strength. When he was 14 years old, he fought with Rustam and nearly defeated him. In TMG, this verse is applied to describe the childhood of Ghazan, Rashīd al-Dīn’s patron. The verse depicts Ghazan as a natural warrior, a quality which befits him as a king.

Fig. 3: Ghazan Khan hunting, Jāmiʿ al-Tavārīkh, (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Division orientale, Supplément persan 1113, fol.212r)

Apart from allegorical situations, Rashid al-Dīn applies poetry in another way to link the Mongols to the Shāhnāma. In TMG, there are 46 verses which are not from the Shāhnāma, but they were composed based on the style of the Shāhnāma. Though the origin of these verses is not known, the meter, vocabulary, and the imagery all remind the reader of the Shāhnāma; a heroic atmosphere which benefited the image of the Mongols rulers of Iran and helped to legitimise them as the rightful successors of ancient Iranian kings. The following verse is an example of this practice in TMG:

9 ز گرد سواران فلک تیره گشت

برفتند و روی زمین خیره گشت

“They went and all the earth sat in a daze, as the firmament turned to darkness from the dust kicked up by the riders.”

The similarity of the above verse demonstrates itself more when compared to the verse of the Shāhnāma:

10 جهان پیش چشم اندرش تیره گشت

چو بشنید رستم سرش خیره گشت

“When Rustam heard, his head sat in a daze, as the whole world turned to darkness before his eyes.”

RṢ and TMG are only two examples of how and why poetry attracts the attention of kings. In the pre-modern era, court history and poetry were tools of propaganda for the rulers who wished to legitimise themselves or make themselves immortal by stamping their names in the pages of history. While various practices were in use according to the demands of the kings, Rashīd al-Dīn and Rāvandī sought to show their patrons as inheritors of the glorious ancient Iranian kings through the art of poetry.

Sara Mirahmadi is a PhD candidate and a teacher of Persian language and literature at Leiden University. With a background in history and Persian literature, she is interested in interdisciplinary research in the two fields of History and Literature. Her work focuses on the ideological aspect of poetry and its role in historiography of the 11th-14th centuries. Email: s.mirahmadi@hum.leidenuniv.nl