Post-coup Repression in Myanmar and Activists’ Struggles for International Attention

Myanmar activists have ample experience advocating for democracy, as the country was under formal military rule from 1962-2010. After ten years of transitioning to a quasi-democratic system, the military (which had maintained a significant political and executive presence) staged another coup on 1 February 2021. It has since violently suppressed an active and diverse opposition movement, which has stepped up both armed and unarmed resistance. How have Myanmar activists transformed themselves and sought to maintain international attention during decades of authoritarian rule? What advocacy points are brought in strategically, and how do they try to secure global support amidst other causes vying for international recognition?

As this article is written, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) has entered its fourth year since the latest military coup of 1 February 2021. The coup, and especially the violent military response to the initially peaceful protests that followed, has caused immeasurable human and economic suffering. All of this has created a political environment that is both volatile and more repressive than before. While in previous eras activists could often outsmart the dated surveillance tactics, the military has since learnt from repressive allies to suppress the population more systematically, including online. According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma), recipient of the Dutch Geuzenpenning Award in 2023, over 26,000 persons have been arrested since the coup, of which a large number remain detained. According to the same source, the military has killed almost 5000 protesters and other dissidents since the coup, including 600 children; in an environment where opposition to the military is so widespread, even primary schools can become a target. In addition to these mostly extrajudicial killings, the State Administration Council (SAC), which has claimed power in Myanmar since the coup, carried out the first death penalties in decades by executing four dissidents in July 2022, including a former parliamentarian for the National League for Democracy (NLD) who was a close ally of Aung San Suu Kyi. The political opposition leader herself, who is nearly 80 years old, has remained detained since the coup and was recently sentenced to 27 years in prison.

Fig. 2: Demonstration after the Myanmar military coup in Amsterdam, March 2021. (Photo by the author, 2021)

Securing international attention

Meanwhile, activists not only have to deal with new traumas and survivor guilt, but also face a strategic challenge: how to keep the situation in Myanmar on the agenda of the international community, which is often preoccupied with conflicts closer to home or of greater geopolitical importance? In his 2005 book The Marketing of Rebellion, Clifford Bob speaks of a ‘global morality market’ where human rights activists continuously compete for attention with other worthy causes. 1 In this analysis the severity of a conflict or human rights violation only plays a small role in determining which causes gain international recognition. Other factors related to the skills, networks, and resources of activists, or the availability of a charismatic leader or spokesperson, also have a significant influence. Bob argues that a movement’s ‘promotional strategies’ are at least as important to its impact on the international community as the content of its message. Having campaigned almost continuously for democracy over many decades, Myanmar activists have had to rephrase their message regularly in order to secure continued attention for their cause and mobilize the international community to support them.

After a large-scale public uprising was repressed in 1988 in the country then known as Burma, many activists fled abroad and continued their activities from exile. This marked the start of what came to be known as the ‘Burmese democracy movement,’ a loose network of organizations campaigning for democratization through various channels and tactics. Initially calling mainly for sanctions and disengagement, democracy activists over time had to reframe their message in the form of different demands, ranging from justice and accountability measures to a boycott of the military-organized elections in 2010 and various forms of investment in Myanmar. This sometimes caused friction with those operating locally inside the country, who accused activists in exile of ignoring local concerns. Yet at times these groups also worked closely together, undermining the military from inside the country while exerting international pressure through transnational platforms.

Fig. 3: Memorial in Paris for victims of

military violence after the Myanmar

coup. Photo taken at the 12th EuroSEAS

conference, June 2022.

As a consequence of the global competition for international attention, activists often frame their message in the form of small, attainable goals and demands that are feasible for international actors to respond to, rather than far-reaching goals that would have a more direct impact on the situation on the ground. Prior to the coup, and especially during the early years of the so-called transition period from military dictatorship to quasi-democratic rule, groups of activists already employed different strategies to gain and maintain international attention for the situation in Myanmar. They formed what Keck and Sikkink call ‘transnational advocacy networks’ that use a ‘boomerang pattern,’ seeking to influence international actors when power holders are not susceptible to domestic pressure. 2 Internationally, they needed to frame their advocacy messages strategically to maximize political, moral, and financial support. In order to achieve this, democracy activists were often forced to simplify the situation in Myanmar by presenting clear culprits, attributions of blame, and required responses. As a consequence, the framing of situations around the aftermath of cyclone Nargis in 2008 or towards the 2010 elections was presented in ways that partially ignored changing realities on the ground. 3

The post-2010 era saw the rise of the so-called ‘Third Force,’ an informal but influential network of intellectuals from Myanmar who claimed to be independent from both the military and the political opposition. This group lobbied international audiences with a message about top-down political change. The ‘Third Force’ organizations quickly gained popularity among Western donors and diplomats, some of whom had grown impatient with the lack of progress made by the democracy movement. They were less popular with grassroots activists, who considered them elitist, as well as with democracy activists, who accused them of supporting the military’s political agenda. Western advocacy consultants who were brought in to train democracy activists presented this diversity of views and tactics as undesirable. When providing advocacy training on the 2010 elections, one noted: “Those apologists from inside the country, who think the elections will provide space, they are more consistent and more powerful in their lobbying… Oppose or support? You need to give a clear message. There is no clear message, because there are different private opinions.” 4 While in a free society diverse views among civil society are more likely to be tolerated and even fostered, in cases of severe repression opposition members are often expected to present unified calls for action towards international actors.

Post-coup struggles for international legitimacy

The latest coup in February 2021 has both intensified and, in some ways, unified opposition against the military. A new generation of activists has grown up with access to social media and opportunities to vote and express their views, and the military miscalculated people’s willingness to continue business-as-usual. The first weeks after the coup saw a large-scale peaceful protest movement against the military, in which student leaders, factory workers, teachers, doctors, and other civil servants united. Many women, youth, ethnic nationalities, and LGBTQ activists publicly spoke out in opposition to the military. Some also displayed solidarity with the persecuted Rohingya, a group whose plight had received more attention from outside the country than from within. Protest messages, banners, and statements were frequently written in English in an attempt to establish a global outreach. As the military increasingly turned violent on protestors, public demonstrations became more rare and ad-hoc, often taking the form of flash mobs, ‘silent strikes’ or protests-without-people, whereby signs or objects are put in public places and shared on social media in an attempt to reduce the direct risk to protestors. Many activists from central Myanmar relocated to border areas under the control of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), where they received military training. Since that time, the military has faced both peaceful resistance and armed opposition from the side of the EAOs and the newly formed People’s Defence Forces.

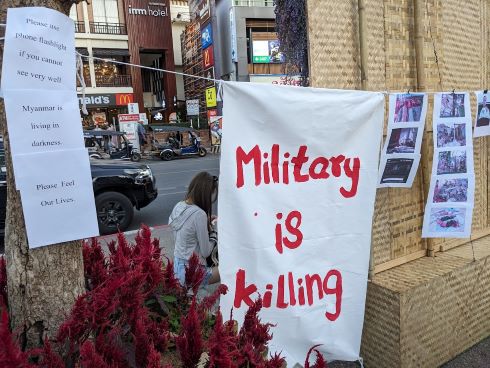

Fig. 4: Protest sign reading “Military is Killing.” Photo taken in Thailand on the third commemoration of the Myanmar coup, February 2024. Photo by the author, 2024.

In addition to this increasingly complex resistance landscape, the post-coup revolution has also been largely leaderless, which complicates the movement’s global advocacy appeal. Opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi has been kept imprisoned since the coup, and her NLD party was eventually disbanded in 2023. A new shadow government, the National Unity Government (NUG), was formed after the coup by elected NLD politicians and leaders of a number of EAOs. Its members frequently participate in international platforms and online events in an effort to establish legitimacy, while weakening the SAC’s claim to power. They have been successful in some respects, for example in the UN General Assembly, where the NLD representative from before the coup has refused to vacate Myanmar’s seat and remains the country’s permanent representative at the time of writing. The NUG has also convinced several Western countries to allow official NUG offices to open on their territory, and it has engaged in various forms of fundraising to support the revolution. Yet internally, the NUG and its associated body the National Unity Consultative Council reportedly lack clear leadership or strategy. They have become subject to the same criticism as activists in earlier decades, namely that they lack a coherent message towards the international community other than a rejection of the military’s claim to power and recognition of the NUG as Myanmar’s legitimate representative body. Moreover, critics consider the NUG insufficiently progressive when it comes to prioritizing ethnic rights and federalist claims, although it has several representatives from ethnic nationalities in its midst.

Calls for international justice

Apart from ad-hoc campaigns such as calls to support Ambassador Kyaw Moe Tun as Myanmar’s UN representative, activists have mainly campaigned for punitive action against the military, including criminal proceedings. In the early years of the political transition, international campaigns centred on a call for the establishment of a UN Commission of Inquiry into crimes committed by the Myanmar military. While the reasons for the call were clear and in fact not new, the timing to bring this up coincided with a period when the democracy movement lost its influence in framing the 2010 elections, as international observers were eager to await the outcome of the military’s top-down transition process. In September 2010, two months before the elections would take place, NLD co-founder Win Tin published an open letter in the New York Times, in which he commented: “I wish that our friends in Europe would abandon their dream of expecting something impossible from the election, and start taking seriously action against the regime with the aim of starting dialogue. They should begin by creating a U.N. commission of inquiry to investigate human rights violations in Burma.” 5

The Commission of Inquiry campaign thus served to draw international attention back to the military’s human rights violations and away from its top-down democratization process. It also provided a clear action perspective, with activists keeping track of the number of countries endorsing their campaign as a way to measure success. International actors that were more hopeful about the military’s transition process, such as the conflict analysis think tank International Crisis Group, considered the Commission of Inquiry campaign unlikely to be successful, and argued that “the international community should focus its efforts on ways to support the process of reform and encourage engagement.” 6 Democracy activists in private agreed that the Commission of Inquiry campaign would not be successful as long as the military remained in power, and one activist suggested that the international community needed to be kept busy with fact-finding and issuing statements. 7 This underlines the hypothesis by social movement scholars that the severity of human rights violations only partly determines why certain campaigns are set up at a particular point in time; strategic considerations also play a decisive role.

International messaging since the 2021 coup

In the more than three years since the latest coup, activists again have had to adapt their calls to the international community’s receptiveness. Only in initial months after the coup did they try to invoke the Responsibility to Protect in an effort to seek direct armed intervention in Myanmar. Yet international responses remained limited to statements, even after the military started killing a significant number of people, shooting at protestors, and bombing presumed hotbeds of resistance. Consequently, activists’ messaging to the international community became more cynical. When the UN Secretary General issued a statement condemning the execution of four dissidents in July 2022, a Kachin activist wrote on Twitter: “We stand in solidarity with the UN for feeling sorry for us. Take your time… we still have millions of people still alive.” 8 Despite widespread resistance to the military, activists came to the realization that no international actors would come to their aid. In fact, they again had to struggle to keep their plight on the international advocacy agendas. Since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, attention for Myanmar’s resistance had been waning. This was exacerbated the following year, when Europe became preoccupied with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Demonstrations in Iran around the same time initially caught international attention, with women publicly cutting their hair in support of female protestors. Compared to these causes, Myanmar lacked geopolitical relevance, a prominent leader such as President Zelensky in Ukraine, or an easily identifiable group of victims; military violence since the coup has been almost indiscriminately against all sections of the population, not only women or particular minority groups. Aung San Suu Kyi already lost much of her international reputation after having been held internationally responsible for the violence against the Rohingya, which she attempted to defend at the International Court of Justice in 2019 – in fact, the violence was orchestrated by Min Aung Hlaing, the same military leader responsible for the 2021 coup. Unlike in previous eras, Aung San Suu Kyi has been held largely incommunicado since the coup, and no opposition leader has been able to take over her symbolic role.

Fig. 5: Protestors in Thailand hold up

the three-finger salute on the third

commemoration of the Myanmar coup,

February 2024.

Activists inside and outside Myanmar continue to come up with new advocacy agendas: a ‘blood money campaign’ to boycott companies affiliated with the military, calls for a ban on aviation fuel (only the military has airpower in Myanmar), and attempts to redirect humanitarian aid away from the military and its affiliated organizations such as the Myanmar Red Cross. These campaigns bring to mind debates about economic sanctions and humanitarian aid in previous eras. Again, they are phrased as goals that are relatively easy for international actors to act on, although they have thus far been only moderately successful. The real needs in Myanmar, as earlier, lie in a permanent removal of the military from all positions of power, an immediate end to the violence against dissidents and internally displaced persons, and large-scale assistance in almost every field, from urgent humanitarian aid to long-term economic and educational support. Additionally, new generations of activists call for a federal democratic system in which the rights of ethnic nationalities and other minorities are fully and permanently acknowledged. Needless to say, such long-term ambitions can only be established by forces inside the country, yet they require consistent support and recognition from international allies.

In March 2024, I witnessed a demonstration on Dam Square in Amsterdam, where the Myanmar community displayed banners calling for rejection of the military conscription order. The conscription order is a newly enforced law by which every citizen under the age of 35 – with different age limits for women and certain professional groups – has become vulnerable to forced conscription by the military, or else face large fines to avoid this. While this law has undeniably had a significant impact on Myanmar’s youth, it was not immediately clear from the demonstration how the Dutch audience is expected to act in response to this information. More encouraging, perhaps, would be expressions of solidarity by activists campaigning for human rights in Gaza, Iran, and elsewhere, some of whom had gathered on the same square at the same time. In previous eras, activists campaigning for Myanmar gained attention by teaming up with Tibet support groups and other like-minded causes. Similar displays of cross-cause solidarity could be established after the latest coup, whereby activists globally join forces instead of competing for attention in the inevitable ‘global morality market’.

Maaike Matelski is Assistant Professor in the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Her research relates to the fields of civil society, human rights, and development, with a particular focus on issues of voice, representation, and legitimacy within rights-based advocacy. Her recent book Contested Civil Society in Myanmar: Local Change and Global Recognition, which is partly Open Access, can be found on the website of Bristol University Press. Email: m.matelski@vu.nl