Politics and Poetics of Land in the History of Indentured Labour in Trinidad

The introduction of Indian indentured labour in the British colony of Trinidad, lasted from 1834 to 1917. During this period, evolving racial taxonomies in Trinidad’s plural society ascribed the “Coolie” label to Indian workers engaged in sugarcane estates of the region as a means to codify their labour in ethnic terms. In an already polarized society this kind of negative ascription further antagonized race relations among Africans and Indians vying for limited resources and employment opportunities. Significantly, the deliberate act of ethnification of labouring bodies had its spatial dimension insofar as East Indian labourers were largely concentrated in the rural belts in and around sugarcane plantations, whereas urban sectors were dominated by ex-slaves. Indo-Trinidadian rural life – stigmatized by a rhetoric of backwardness, cultural insularity, and political indifference – went on to structure the indentured workers’ and their descendants’ relationship with land. At the same time, communal living allowed a semblance of cultural continuity with the homeland, while helping them negotiate their place within a culturally alien society. In the process, rural land possession became a marker of stability as well as an opportunity for backward caste groups to re-write their ‘fate.’ Thus, in the collective consciousness of this ethnic group, the “Coolie” identity became intrinsically linked to contradictory impulses originating in a notion of ‘land’ that was both constricting and liberating.

The distinctiveness of ‘land’ as a stable category marked by the cartographic tyranny of Empire was in fact destabilized by instances of flight, dispossession, violent assertions of ownership, and reclamation of an altered sense of belongingness by the estate worker. In the post-indenture period, changing socioeconomic circumstances have produced rural-to-urban migrations within Trinidadian society, thereby making urban-centric land negotiation a new factor in acquiring status. ‘Land-locked’ narratives offered by colonial ledgers and reports thus prove inadequate towards understanding the essentially transoceanic nature of indenture legacies. The inherent fictiveness associated with practices of labour recruitment and management, with enduring consequences for future generations of diasporic Indians, points towards the significance of alternate forms of ‘story-telling’ by descendants of indentured labourers. A literary analysis of the same, focused on an ongoing process of negotiation with evolving ideas of land ownership and aspiration in post-colonial Trinidad, would help understand the tangible and affective dimensions of the community’s homing desire far away from ‘home.’

Context

The 1833 Act of Abolition of slavery in British colonies prompted planters in the Caribbean and Mauritius to devise other means to address the problem of acquiring cheap labour for their estates. 1 A heterogeneous labour force in early 19th century Caribbean occasioned by the gradual termination of the shipping of African slaves challenged the plantocracy’s “ideal model” by disrupting systems of labour control previously designed to maximize profit. Part of this coercive mechanism entailed “a blend of demographic and psychosocial perceptions” inherent to the system of labour allocation. 2 Consequently, apart from low wages, arbitrary racial taxonomies were devised to exacerbate inter-racial antagonisms as a counter to solidarity movements among diverse working-class populations agitating for better work conditions. The logic of efficiency governing monocultural regimes of the Caribbean depended on remembering and re-instituting such ‘essential’ cultural differences. It explains the persistence of strategies of “competitive victimhood” underscoring Afro-Trinidadian and Indo-Trinidadian politics in the Caribbean region both before and after independence.

Gaiutra Bahadur traces the evolution of the ‘Coolie’ label (from the Tamil word ‘kuli’/ கூலி meaning wages or hire) from its first usage in the late 16th century by Portuguese captains and merchants along the Coromandel Coast in India to denote “the men who carried loads at the docks,” to its broader lexical definition of cheap unskilled labour from Asia. 3 In the 1830s the term came to be identified with indentured labourers recruited by the British government to work on colonial plantations. As a homogenizing tactic, the label sought to erase caste-class distinctions while signifying the group’s racially-determined marginalization in the hierarchized sugar estate. Yet, the reductive “Coolie” ascription underscored contradictions inherent to this “technology of emigration”V launched by British administrators. While the indenture system was projected as being far removed from the excesses of slavery, it was nonetheless a thoroughly exploitative regime based on the urgent economic needs of Empire. The plantation labourer’s association with the land on which he toiled was defined by a series of lies, obfuscations, and myth-making necessary for the sustenance of the capitalist order. It was therefore at this discursive juncture that the ‘coolie’ identity was both formulated and challenged.

With reference to the history of Indian indentured labour recruitment, the trauma of displacement and desire for an altered sense of homecoming are both tied to the politics and poetics of land. Several patterns of displacement brought potential recruits to the Calcutta depot. Factors such as an increase in taxation, de-industrialization, commercialization, colonial expropriation, draught, famine, population density, and caste-related incidents produced a landless peasantry and prompted migration towards other districts and cities. Here labourers enlisted for the Caribbean were offered a vision of plenty in which land ownership figured prominently for those who had been dispossessed of home and hearth. However, the myth of the Caribbean as a labourer’s paradise was countered by realities of an incongruous inter-continental system. Instances of disorder and rioting on the plantations attested to the extent of misinformation fed to recruits at the depots regarding the nature of their work. Even as the coolie was subjected to a regime of colonial stratification, all such attempts at initiating him into a rigid penal regime were undercut by the government’s own efforts at grounding indentured labour recruitment in a narrative of ‘consent.’

Negotiating land, literacy, and aspiration

At the heart of the narrative of consent lay the issue of choice, predicated on a five-year tenure of indentured labour. At the end of his term a labourer could return to his native place or extend his work tenure or even dissociate himself from the indenture system by choosing to remain in the colony and engage in other kinds of occupation. Yet the illusory nature of ‘choice’ became evident. Often the promised wage was not paid upon entering into the system, which in itself obstructed plans of return and re-settlement in one’s native place. In the 1860s, Crown Lands around the “sugar belts” of Southern and Western Trinidad were offered primarily in exchange for a return passage and later for both lease and sale. This led, to a certain extent, to the proliferation of Indian villages inhabited by ex-indentured labourers engaged in independent cane farming and subsistence agriculture. In reality, however, such lands were hard to come by. The merchant-planter class had absolute monopoly over land which enabled them to bind labour to the estates and discourage subsistence farming. Crown Lands were expensive, and governmental policies discouraged squatting, such that land could be kept “out of the reach of the masses in order to preserve the estate labour force”; moreover, a biased justice system instituted severe penalties for violation of governmental labour laws. 4 At the same time, racialized narratives of rural-urban divide – predicated on the black-white axis of Trinidad’s plural society to which the Indian had arrived late and subsequently been relegated to a separate tier – posited the post-indenture Indian community of Trinidad as a backward, inward-looking, and socio-culturally alien agricultural group. 5

Land was an ambivalent legacy of indenture. “Coolies” and their descendants both aspired toward the security and self-sufficiency offered by it, but at the same time, longed to escape the entwined association between rurality and backwardness. In the run-up to Trinidad’s independence (1962), and after, the correlation between rural residence and socio-economic backwardness was strengthened by the notion of status acquisition concentrated on the industrialized city centre with its emphasis on professional jobs. Although a small group of urban Indians constituted the rising middle class engaged in the professions or operating as small businessmen, a majority of them remained tied to the agricultural land in popular imagination. The question that arises at this juncture is regarding the value of land as an aspirational commodity inevitably linked to a traumatic past. While the acquisition of Crown lands close to the estates offered means of subsistence away from the horrors of indenture work, it was the same ancestral land which came to the descendants as generational trauma linked to the inception of the “Coolie” designation in the depots of Calcutta. It was the same land which referred to the sugarcane estates where land and labouring body were conflated within an economy of social stratification. If the propensity of the indentured body was to bend, or twist, or fold, then this instinct became a kind of psychological inheritance which successive generations of Indian immigrants sought to reverse by securing their bodies out of the fields through education and migration to the cities.

In colonial Trinidad literacy and ethno-religious identity have had deep links, particularly for East Indians. Perceptions of backwardness regarding the Indians’ religious practices and cultural habits – buttressed by a system of Christian missionary school education – often presented literacy itself as a contentious topic. While fears of cultural assimilation acted as a deterrent for many Indians who felt that their traditional institutions were at risk given the pedagogical structures governing colonial missionary schools in the region, literacy was also regarded as a means to rise above their denigrated status. Conservative religious bodies such as the Hindu Mahasabha, operating primarily as cultural gatekeepers for the larger Hindu community in Trinidad, were often in conflict with modernizing trends among middle-class Indians, for whom colonial education offered access to the political life of the Caribbean. Ambition among Indo-Trinidadian descendants of indentured labourers has thus been seen as a complex of racial, ethno-religious, and social factors indicative of the “assumed antagonisms of Afro- and Indo-Caribbean people.” 6

Contemporary literary interventions

The centrality of spatial signifiers of status and prestige based on evolving notions of land in a developing nation has been of particular concern to Indo-Trinidadians, who had arrived belatedly in a racially stratified nation. The colonial myth of light labour and plentiful land fed to a vastly agricultural population – alienated from their native soil for a variety of reasons – couched indentureship in the language of reclamation, albeit in newer forms, in radically altered surroundings. Rural Indians’ relationship with land, mediated as it was by caste-class and gender distinctions, had its affective dimension insofar as visions of the native village evoked both communal feelings of rootedness and memories of discrimination. What the indenture scheme offered was attractive social and economic dividends minus the horrors of poverty, hunger, and caste and gender violence. In the contemporary literature of Indian-origin writers reflecting on Trinidadian society, the imbrication of literacy, social mobility, and apprehensions of cultural loss among descendants of indentured labourers has been a recurrent theme inhering in notions of rootlessness and re-possession. If the originary point of access to an altered reality is the estate land offered in popular colonial discourse as the land of possibilities, then how far does the reality of incarceration and dehumanizing labour allow both ex-labourers as well as descendants of indenture to re-imagine land acquisition as a wholly separate and disconnected act? Here ‘land’ is variously configured as a performative arena where both generational trauma and modern aspirations are interlocked entities.

Indo-Trinidadian author Shani Mootoo’s 1996 novel Cereus Blooms at Night describes Ramchandin as a lower-caste indentured labourer from India whose presence in the barracks of the fictional island of Lantanacamara raises the possibilities of slipping out of his inherited destiny as a lowly labourer. Ramchandin and his wife imagined that by honouring the demands of labour, the indenture estate could function as a dynamic site for articulating a radically separate future for their son. Yet the monocultural logic of estate land does not allow that. Wendy Wolford’s recognition of the plantation as an ideal for “organized, rational, and efficient production and governance,” by which all other landscapes and people are alienated, attests to the dominant work ethic of this system of labour. 7 The pervasive nature of this ethic of productivity was equated in old man Ramchandin’s mind with the folklores of plenty, liberty, and opportunity fed to potential labourers by recruiters back in India. However, the desire to “educate Chandin out of the fields” was undercut by Chandin’s own troubled relationship with an inheritance that was both biological and social; the plantation logic of indentured labour claimed the labouring body as part of the larger organization of capital while lacerating future generations with the trauma of this legacy. In fact, Chandin’s desire to educate himself out of his troubled legacy does not discriminate between the sugarcane estates to which his parents were bound and the land which they acquired later as free agricultural labourers. Both constitute an uninterrupted terrain whose texture and essence would not change so long as the labourer’s body was indelibly signified as the site of cultural backwardness, atavistic religious practices, and servility.

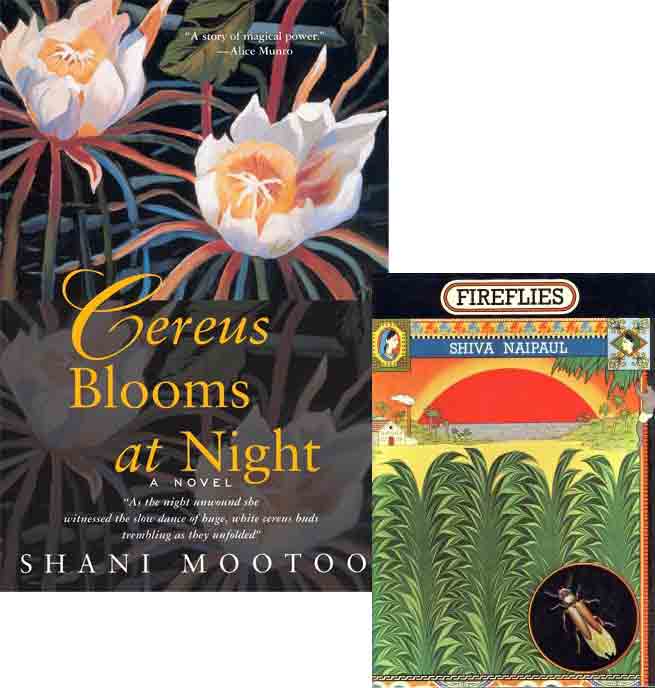

Fig.2: Covers of Cereus Blooms at Night by Shani Mootoo (Published by HarperCollins, 1999) and Fireflies by Shiva Naipaul (Published by André Deutsch, 1970)

Chandin himself is unable to dissociate between the generational shame characterizing his family’s relationship with land and his own homing ambitions. When he buys cheap land in an underdeveloped locality, he is struck by the persistence of a feeling of captivity and failure attending his desire to build a life unburdened by history. The sense that his parents suffered from a poverty of ambition is projected on to the wooden house he builds in the typical style of modest Indian dwellings. In the novel, existing modes of racialization structure Chandin’s material and affective relationship with land and agricultural labour. The ghost of the plantation bears upon other practices on the land insofar as the intimate relationship between indentured labour and subsistence farming continue to generate contradictory emotions. Chandin’s self-loathing is mediated both by his consciousness of the black-white axis of society, by which dignity and status are determined, as well as his belief in the binding effect of indenture land on the mind and body of his father.

With regard to the Indian community of Trinidad, Nobel laureate V. S. Naipaul has referred to their cloistered village lives as being devoid of any sense of time and history. Rural Indian diaspora’s cultural poverty was, in Naipaul’s estimate, due to the absence of a “framework of social convention” which might have produced a culture of reading and writing. 8 What remained of India was a simplistic rendering of Indian village life without the kind of social stratifications which had anchored them to their subcontinental reality. In a sense, cultural insularity based on a collective anxiety of assimilation had been achieved at the cost of economic and political deprivation. Naipaul’s description of a typical Indian village in Trinidad is scathing in its critique of an aesthetic of quaintness and tradition, masking the community’s inherent backwardness. As explicated in his 1961 novel A House for Mr. Biswas, the battle between clan life and individualistic aspirations would no longer be fought over the possession of a piece of rural land meant to simulate a constrictive communal identity. Looking towards the more culturally heterogeneous city, epitomized by Port of Spain, Mr. Biswas envisions a radically modern dream of building a home which would be strictly his own, in his own name. Although the protagonist’s struggle is couched in the language of failed rebellion, the poignancy of his condition inheres in his belief in social mobility as an escape from the stronghold of ancestral land and its associated racial prejudices. This shift towards the city reconfigures diasporic longings for home since the emotive potency of rural land as the site of identity preservation lessens over time with changing societal conditions.

V. S. Naipaul’s younger brother, Shiva Naipaul explores this rigid aspect of clan life among rural-based tradition-bound Indo-Trinidadians in his 1970 novel Fireflies [Fig. 3]. Much like A House, Fireflies also explores the theme of aspiration as a breakaway from the toxic confines of family hearth and home. Here the Khoja clan is representative of the anti-assimilationist camp whose legitimacy among fellow Indians derived from its rejection of modernity. Those who had sold off their lands in predominantly Indian rural belts and established their home in the city, ‘joined the professions,’ or converted to Christianity are seen as betrayers of the community. The projection of the postcolonial city as a land of opportunities was counteracted by apprehensions of a racially biased process of creolization necessarily stripping the Indo-Carib of his cultural identity in the name of integration and mobility. The industrializing city became the epicentre of socio-economic opportunity for both working- and middle-class Indians migrating out of a typically agricultural economy, while enclaves of elite Indian residences, professions, and businesses carved out newer avenues of power and prestige. The desire to be integrated, thus, reformulated ‘land’ in the imagination of aspiring Indians. It became imperative for many middle-class Indians to integrate themselves within the emergent economic order occasioned by global neoliberal trends and national modernization efforts concentrated on urban centres. To own land in certain upscale urban locales became both an assertion of status in Trinidadian plural society as well as a means to become relevant within the political process. The effort was also to disengage from the enfeebling legacy of the “Coolie” identity and its connections with rurality in popular discourse.

In Shani Mootoo’s 2005 novel He Drown She at Sea, urbanized conclaves dominated by elite Indians in the fictional Caribbean island of Guanagaspar highlight the divisive nature of intracommunal relations between educated middle class Indians on one hand, and rural working class Indians on the other. The focus here is on the possession of land recast as modern concrete homes in exclusive neighbourhoods as opposed to traditional wooden houses built on mudra stilts characteristically associated with Indian villages. In the context of Fireflies, the abandonment of rural land by Indians and the investment of that money towards gaining access to a more cosmopolitan sphere of influence involved acquiring an English education, speaking predominantly in English, becoming doctors and engineers, and buying lavish homes in the city. While the Khojas cast such tendencies in negative terms, Naipaul’s critical lens is directed primarily at the thousands of acres of poorly cultivated Khoja land that had become empty signifiers of their fiercely protected backwardness. The novel refers to the utter destitution of the countryside dominated by villages named after Indian cities such as Lucknow, Calcutta, and Benaras. The visual metaphor of villages lost among sugarcane fields makes it impossible to disassociate plantation from independently owned land. This spatial overlapping also conflates history and myth, foregrounded by the vision of indigent peasants and their children returning from the fields. Much like Mr. Biswas, the protagonist of Firelies, Ram Lutchman, soon learns that all this land belongs to his in-laws’ family, the Khojas. Crucially, a feudal logic of control dominates the clan’s ownership of land, and in Ram’s mind, acknowledgment of his own troubled association with the Khojas would arrest him within that timeless image of quaint Indian village life.

Following the oil boom (1973-1982), when OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) raised the price of Arabian crude oil and Trinidad (a non-OPEC member) could make a profit by selling its own crude oil at a much higher price, most of the economic benefits were concentrated in the urban sectors. It was equally the case that the PNM government headed by Eric Williams was often perceived by Indians as an urbanized African party averse to programmes of actual wealth distribution among all groups. The simultaneous decline of the agricultural sector generated a need for other sources of employment. Thus, the city re-imagined ‘land’ as a source of status creation in response to the changing economic conditions, which in turn accelerated the rate of rural-urban migration and triggered urban stress and unemployment primarily among working class Indians and Africans. Urban squalor caused by unidirectional migratory trends produced urban surplus labour and aggravated the problem of “structural imbalances between urban and rural areas.” 9 It is no wonder then that successive Indian-origin authors have sought to interrogate the intra-communal dynamics between Indians residing in upscale urban enclaves of Trinidad and those inhabiting peripheries of the city centre. What becomes evident through such literary interrogations is the fragile nature of the rhetoric of loss-induced camaraderie among Indian indentured labourers migrating across the world.

Shayeari Dutta holds a PhD from the Centre for English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her current work focuses on Indo-Caribbean diasporic literature and indenture histories of the Caribbean. Email: dutta.shayeari@gmail.com