Pedagogies of Partition: Collective Memory and Counternarrative 75 Years On

Seventy-five years ago, the world witnessed one of the largest migrations in recorded human history: the Partition of India and Pakistan. An estimated 14 million people were uprooted from their homes, driven by violence or the fear of it as the newly independent nations of India and Pakistan were born from the subcontinent’s long struggle for freedom. After 300 years of British economic intervention and, later, political domination, the new nations were formed in August of 1947. India had a majority Hindu population (though it was envisioned to be a secular country), and Pakistan had a Muslim-majority population. The new nation of Pakistan was divided into East and West Pakistan; East Pakistan later fought for its independence and became the nation of Bangladesh in 1971.

In the lead-up to Independence from British colonial rule, which had politicized South Asian religious identities in new ways, vigorous debates were held about whether to divide – or “partition” – into two countries. Splits within the independence movement, represented by the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, prevented a consensus on power-sharing formulas and guarantees for the rights of Muslims in a Hindu-majority India. Ultimately, then-British Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten, enlisted a British judge Cyril Radcliffe to draw the borders of the new countries, though he had never been to the region. The new borders were only announced by the departing British days after India’s and Pakistan’s independence. As tensions were already on the rise, many began migrating prior to the official announcement.

From 1946 to 1948, an estimated 14 million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs headed in both directions, many forcibly driven out by violent extremist groups on both sides. Unspeakable violence engulfed this large human displacement. An estimated one to two million people were killed, and hundreds of thousands of women were victimized by sexual violence. 1 in order to more effectively “divide and rule” 3 or to attempt to solve ethnic and religious tensions that the British had previously fostered, as evidenced in the earlier partitions of Afghanistan (1893), Bengal (1905), and the Ottoman Empire after World War I (1918-1922). Newberry notes that from 1870-1914, “Everywhere in British Africa, partition changed the cultural landscape.” 4 The legacies of these partitions are long-lasting, and even today, they certainly continue to impact world politics and possibilities for peace.

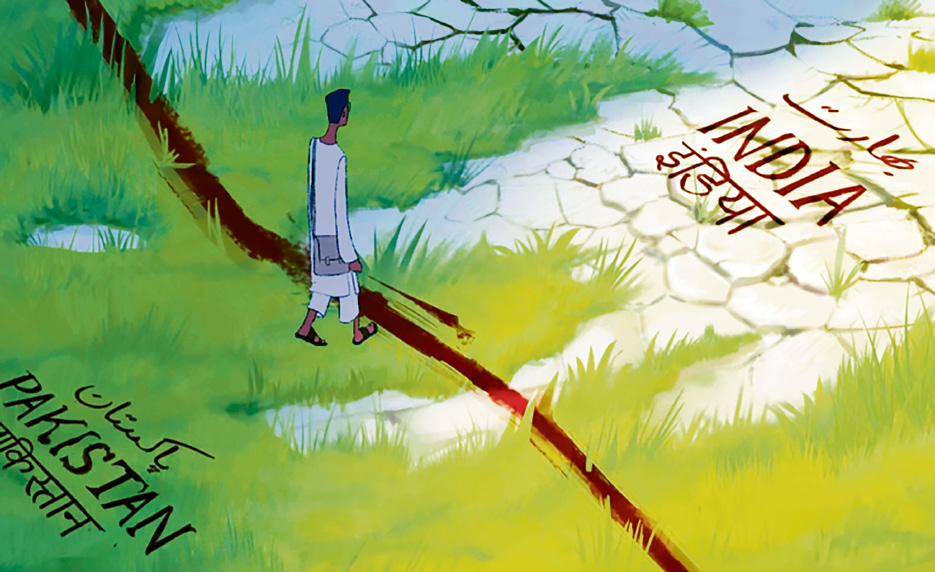

Fig. 1: A still from the short film “Rest in Paper,” directed by Haseeb Rehman as part of the Lost Migrations project (Photo courtesy of Puffball Studios, 2022).

The 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan – given the magnitude of displacement and death – certainly deserves greater attention in our education systems and public consciousness globally. The 1947 Partition is rarely included in discussions of world history, and where it is, such as briefly in textbooks in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the United Kingdom, there is a focus on “us and them” and singular narratives. They tend to be silent about the violent outcomes of Partition, as educational scholar Meenakshi Chhabra discusses in her extensive research and textbook analyses about the historical event. 5

One-fifth of the world’s population lives in South Asia (accounting for nearly two billion people), a region comprising the nations of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The South Asian diaspora across the globe also numbers an estimated 24 million. For those with South Asian heritage, and also for those without this heritage, teaching about the 1947 Partition as an important event in world history offers a corrective to the silence and invisibilization of this history to date.

My own family’s trajectory was greatly impacted by Partition through the loss of family members, their sudden displacement as refugees, and the lasting intergenerational trauma that all of it caused. As an educational scholar, I offer three areas through which we can engage the pedagogies of Partition in our classrooms, communities, and beyond to learn from this painful history: (1) humanizing Partition through children’s literature and curriculum; (2) public pedagogies and counternarratives of Partition; and (3) efforts towards peacebuilding and solidarity. Education – both inside and outside of the classroom – offers important analytical frameworks as we grapple with understanding contested historical events like the 1947 Partition; it also provides a way to develop a “people’s history” of Partition, one that can foster a more expansive collective historical memory, one which transcends the political agendas and projects of nation-states.

Humanizing Partition through children’s literature and curriculum

Whether in schools, libraries, or even the books read at home, the increasing number of Partition-related stories in recent years offer multiple perspectives on this event through the hopes, realities, and experiences of the characters in the texts. The following texts at the primary and secondary levels can introduce readers to stories about the Partition.

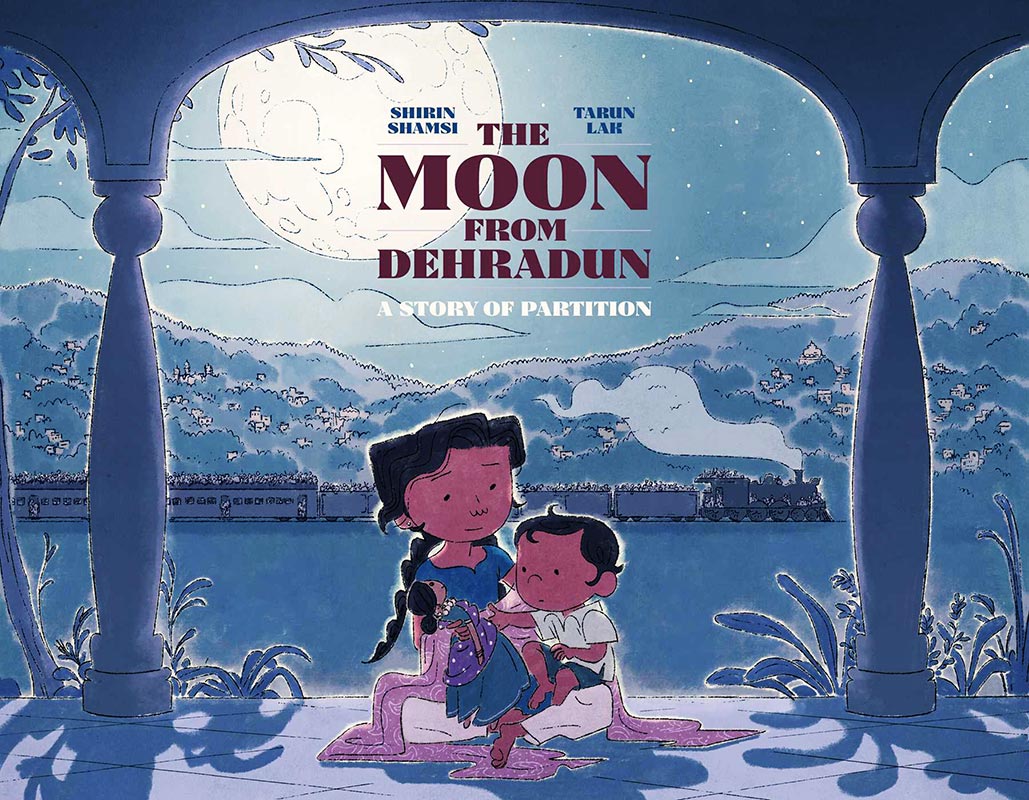

At the level of upper primary school, three titles deserve special mention. First is Chachaji’s Cup 6 by Uma Krishnaswami, illustrated by Soumya Sitaraman. This picture book, for which there is also a teacher’s guide, 7 tells the story of an Indian-American boy and his grand-uncle, whose special teacup is the only item that the elder still has from his childhood home. There is also a page at the end of the book that offers a brief history of the Partition that could be shared with students as well. The second book is Mukand and Riaz 8 by Nina Sabnani. This picture book – which has also been rendered into a short animated video 9 – is set in 1947 and tells the story of two boys (Mukand and Riaz) who enjoy playing together. When the news of Partition comes, they must say farewell to one another, and Riaz helps Mukand and his family depart for India safely. The third book at this level is The Moon from Dehradun 10 by Shirin Shamsi, illustrated by Tarun Lak [Fig. 2]. This is a picture book about a young girl who has to leave her favorite doll behind during her family’s migration from India to Pakistan during the Partition. The beautifully illustrated story, with an informative note on Partition at the end, allows readers to relate to the uncertainty felt by migrants forced to flee violence and seek safety.

Fig. 2: The Moon from Dehradun by Shirin Shamsi, illustrated by Tarun Lak (Atheneum Books for Young Readers [Simon & Schuster], 2022).

There are also engaging titles aimed at slightly older readers at the middle and secondary school levels. The Night Diary 11 by Veera Hiranandani, tells the story of Nisha, a 12-year old girl who has a Hindu father and a deceased Muslim mother [Fig. 3]. Nisha recounts her family’s refugee journey during the Partition through a series of letters to her mother in her diary. The publisher’s website includes an open-access educator’s guide 12 and the book received the Newberry Honor as a “distinguished contribution to American literature for children” in 2019. A sequel to The Night Diary about the characters’ lives after Partition will come out in 2024. Another title at this age level is A Beautiful Lie 13 by Irfan Master. In this young adult novel set in 1947 during the weeks before Partition, 13-year old Bilal, a Muslim boy in India, devises an elaborate plot with his friends to keep the news of the Partition and its related violence from his dying father, who would find the division of the countries heart-breaking. Like Chachaji’s Cup and The Night Diary, A Beautiful Lie also offers an extensive educator’s guide online. 14 Finally, The Partition Project 15 by Saadia Faruqi is a forthcoming (2024) middle-grade book about a young girl, Maha, whose curiosity and budding interest in journalism leads her to explore her family’s experiences during the Partition of India and Pakistan, causing rifts with family and friends who do not understand her fascination with this history.

Fig. 3: The Night Diary by Veera Hiranandani (Penguin Random House, 2018).

Other resources that could be explored in classrooms or community spaces include a six-minute video from TED-Ed – “Why was India split into two countries?” 16 – and curricula from the University of Texas 17 and Stanford University. 18

Public pedagogies and counternarratives of Partition

Public pedagogies refer the ways that learning occurs outside of formal institutions and within public or community spaces. One “public pedagogy” of Partition is the extensive 1947 Partition Archive 19 – a treasure trove of information with nearly 10,000 oral histories of individuals who survived the Partition. An interactive map on their webpage can help users locate stories, explore migration routes, and read summaries of survivors who moved in different directions. Coverage about the Archive from the New York Times, 20 as well as the organization’s YouTube channel, 21 can be useful ways for anyone – young or old – to engage with first-hand accounts and experiences of Partition. The organization’s website also hosts a “Partition Library” with extensive lists of films, books, and web resources that address the historical event and its legacies. 22

Museums dedicated to the stories of Partition have also emerged. For example, one can visit or take a virtual tour of the Partition Museum in Amritsar, India, exploring online images of collection items, videos, and articles about the museum. 23 There is also a Kolkata Partition Museum that is primarily virtual at present. 24

Recent shows and videos in popular culture have addressed the Partition in different ways. For example, in his short music video “The Long Goodbye,” which received an Oscar in 2022 for best live-action short film, actor and musician Riz Ahmed discusses the multiple displacements of his family from India to Pakistan during Partition then, later, to the UK. 25 The 2022 six-part fictional series Ms. Marvel explores the superhero Kamala Khan’s origin story, which centers around her great grandmother’s experiences during the 1947 Partition. 26 Several episodes include archival and fictional footage of families fleeing violence, offering a window into this historical period through popular culture.

Archives, museums, films, and shows visibilize the complex and layered experiences of Partition. Exposure to multiple narratives can be an opening to discuss these events, but caution is required to not fall into the singular narratives of “enemy/victim” and “us versus them” that have been galvanized by political leaders in different nation-states.

Efforts towards peacebuilding and solidarity

Attention to agency and solidarity, as well as counternarratives to dominant discourses, can help avoid the traps of simplistic tropes around Partition that have fueled enduring hate and division across nations. It is essential to highlight stories of solidarity as well as to critically analyze how political leaders have leveraged singular narratives for their own agendas over the past 75-plus years. Shedding light on lesser-known stories of Partition can also further illuminate the diverse and complicated realities of this period.

One such effort is a joint, publicly available text produced by the History Project entitled Partitioned Histories: The Other Side of Your Story. 27 The project, collectively developed by Indian and Pakistani educators and scholars, presents 16 chapters in a nearly 300-page book; each chapter has the Indian and Pakistani narratives of historical events side-by-side, as culled from history textbooks in both nations. As the authors of the book note in the introduction when referring to the book’s last chapter, “The Partition of India, with which we conclude, is arguably the most important of these events and it is still the reason for the rift between people on either side of the border, a rift that we hope to interrogate, transform, and even heal by doing history differently.” The placement of conflicting narratives side-by-side offers a chance for the reader to zoom out and question why such narratives have been produced, by whom, and in the service of what agendas.

The organization Project Dastaan is a “peace-building initiative which examines the human impact of global migration through the lens of the largest forced migration in recorded history, the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan.” 28 The organization uses virtual reality (VR), with footage compiled from volunteers, to allow survivors of Partition to visit their childhood homes through VR headsets, as opposed to navigating the turbulent political terrain of securing visas or traveling long distances across hostile borders. With teams from across the South Asian region, the organization also produces videos like “Child of Empire,” a virtual reality “docu-drama experience” of the 1947 Partition. 29 The organization also recently produced three short animated videos entitled Lost Migrations to shed light on “hidden stories” of Partition, such as the experiences of women, South Asians in Burma, and those who became stateless after 1947. 30

Brazilian educational scholar Paulo Freire has argued, “Looking at the past must be a means of understanding more clearly what and who [we] are so that [we] can more wisely build the future.” 31 The role of critical inquiry and education as the pursuit of greater freedom requires a nuanced understanding of history and how asymmetries of power are interwoven with colonialism, imperialism, and lingering structures of violence. By exploring pedagogies of Partition in our homes, classrooms, and communities, we can better understand the dimensions of global conflict and possibilities for peace and justice in our world today.

Additional Resources

- “The Great Divide” in The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/06/29/the-great-divide-books-dalrymple

- “How the Partition of India Happened” in The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/how-the-partition-of-india-happened-and-why-its-effects-are-still-felt-today-81766

- “Young Indians and Pakistanis Rewrite their Shared History” in NPR: https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2014/08/17/340687306/young-indians-and-pakistanis-rewrite-their-shared-history

- “From post-memory to post-amnesia: Remembering and forgetting East Pakistan” in The Daily Star (Bangladesh): https://www.thedailystar.net/star-weekend/postmemory-post-amnesia-1452601

- “South Asian diaspora brings 1947 partition to Western pop culture” in Al Jazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/8/11/south-asian-diaspora-brings-1947-partition-to-western-pop-culture

A previous article by the author on Teaching Partition, that this articles draws from, can be found here: https://medium.com/@mibajaj/teaching-about-south-asias-partition-673287eaad98

Monisha Bajaj is Professor of International and Multicultural Education at the University of San Francisco. She is the editor and author of eight books and numerous articles on issues of peace, human rights, migration, racial justice, and education. Email: mibajaj@usfca.edu; website: www.monishabajaj.net