Parindra’s loyal cadres. Fascism and anticolonial nationalism in late colonial Indonesia, 1935-1942

In 1945, with the horrors of the Second World War still very much around him, George Orwell made the following observation in his essay Notes on Nationalism: “It is important not to confuse nationalism with mere worship of success. The nationalist does not go on the principle of simply ganging up with the strongest side. On the contrary, having picked his side, he persuades himself that it is the strongest, and is able to stick to his belief even when the facts are overwhelmingly against him.” *

The last sentence of this quote contains an important element: the nationalist persuades himself, which implies that, at least at times, he loses faith in his project – the (independent) nation-state – in pretty much the same way an entrepreneur might lose hope in his pursuits while building an enterprise. Top-down approaches to political history, nationalism, and intellectual histories focusing on the genesis of ideas and worldviews often presuppose an inevitability and seemingly ‘organic’ development that most probably did not appear to historical actors in their times. Granted, some nationalists were veritable zealots who worked tirelessly to make their dream come true. But many others, no less tireless and diligent, in all likelihood went through periods of doubt, especially when circumstances seemed dire. The pragmatists within nationalist movements, on the other hand, may have looked at nationalism as a means to an end, such as long term benefits and a better future for themselves and their families. For them, the national community was not just a matter of imagination and infatuation, but a strategic step towards furthering their personal interests. Nationalists were, therefore, a diverse cast of characters from all walks of life brought together by the appeal of the same idea, but not necessarily driven by the same motivations. And of all the nationalists, it is likely that the pragmatists from the upper ranks of any given nationalist movement were most aware of the need for self-persuasion – persuading themselves, but also persuading followers who became tired, frustrated, and disillusioned.

Tilting at windmills: Soetomo and the nationalist milieu between 1935 and 1942

In late colonial Indonesia during the second half of the 1930s and the early 1940s, only the pragmatists within the nationalist movement still stood a realistic chance of pushing their agendas. The nationalist ‘hardliners’, including Indonesia’s president-to-be, Sukarno, were exiled, arrested, or otherwise silenced by the mid-1930s. From then on, only so-called ‘cooperating’ nationalist parties, such as Partai Indonesia Raya (Parindra; Great Indonesia Party) and the more left-leaning Gerakan Rakyat Indonesia (Gerindo; Indonesian People’s Movement) that accepted Dutch authority and were willing to articulate their interests through the Colonial Council, the Volksraad, were granted the right to exist. Any open demand for independence [kemerdekaan] was considered dangerous and had the potential to provoke fierce countermeasures from the Dutch colonial government. As a consequence, leading members of Parindra, most notably Soetomo, the party’s founder and a well-known pioneer of Indonesian nationalism ever since the 1910s, replaced demands for Indonesia merdeka with invocations of a ‘glorious Indonesia’ [Indonesia moelia]. Soetomo envisioned the path to glory as a process of moral and spiritual ennoblement for all Indonesians, which was to be achieved through discipline, unity, and harmonious collaboration. On the other hand, arguments and dissent – the hallmarks of any truly democratic society – did not rank very highly on Soetomo’s list of desirable attributes. While he was without a doubt an enthusiastic modernizer who embraced the virtues of material progress and dedicated his life to the tremendous task of promoting education for his compatriots, his traditionalist values stood in sharp contrast to his modernist outlook.

Fascism in Indonesia: a blind spot?

One dark and rarely acknowledged aspect of Soetomo’s political activism, throughout the 1930s until his untimely death in 1938, was his sympathy for Fascism, National Socialism, and other far-right and authoritarian movements the world over. From the viewpoint of Europeans, who typically frame the rise of fascism and authoritarianism in the 1920s and 1930s with the sociocultural dislocations caused by the First World War and amplified by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, fascism was a particularly belligerent permutation of ultra-nationalism and irredentism. Such movements existed all over Europe, and scholars tend to highlight their reactive nature, pointing out that fascism needs to be understood within the larger historical context of the interbellum period in Europe. This Eurocentric understanding of fascism dominated research until the early 2000s, when a small handful of publications slowly started to look at fascism’s broader entanglements. But even now, in 2019, it is still safe to say that research on fascism is woefully Eurocentric. How can we explain the emergence of fascist activism in Japan, China, Egypt, the Middle East, or India?

Parindra’s leadership, including Volksraad member Soekardjo Wirjopranoto (front left), are greeted by ‘Wirawans’ during Thamrin’s funeral on January 12, 1941.

The academic literature clearly shows that fascism, which was for a long time perceived as an ideology too specifically European and chauvinistic to be appealing for colonized peoples, was very much part of a global wave during the interwar years. The most innovative aspect of my work on fascism, apart from pointing out that Indonesia has a tradition of paramilitarism that precedes Japanese occupation (a point I shall return to later), is that it paints a more nuanced portrait of Indonesia’s path to nationhood. Much valuable research has been done on the genesis of Indonesian nationalism, but none of it engages with the obvious philo-fascist views of some Indonesian nationalists, including Soetomo. Why is it that so much academic literature has been produced on political Islam and communism in Indonesia during the 1920s and 1930s, while fascism has no place in hallmark publications on Indonesian nationalism?

One obvious point is the ‘European bias’ of fascism that I pointed out earlier. For similar reasons, it was only recently that non-European countries, besides Japan, were identified by scholars as players in fascism’s global political arena. In the case of Indonesia, however, we also need to include factors specific to the country and its historiographical tradition. In hindsight, the arrival of the Japanese in March 1942 overshadowed any previous attempts at building a paramilitary infrastructure and militarizing larger parts of Indonesian society. As a consequence, magisterial works on Indonesian (para-)militarism, such as Robert Cribb’s Gangsters and Revolutionaries and Benedict Anderson’s Java in a Time of Revolution generally skip the period of ‘cooperative nationalism’ by jumping from the defeat of Soekarno in 1934 straight to the landing of the Japanese in 1942. If we follow the historiographical mainstream, Parindra was an upper-middle-class party that was seeking pragmatic arrangements with the Dutch and only radicalizing as the prospect of Japanese occupation drew nearer,1 hoping that Japan would liberate the Dutch East Indies from foreign rule once and for all – which, as we know, was a dream that was soon to disappoint. Yet, this is only one part of the story, and once we pay closer attention to Parindra’s grassroots activism and its youth organization Surya Wirawan [Sun of Heroes], a different image emerges.

‘Doing fascism’ in late colonial Indonesia

As photographic materials promoted in the party’s own journal Soeara Parindra [Voice of Parindra] repeatedly show, Parindrists and the young men who served in their ‘scout organization’ Surya Wirawan had a particular weak spot for open displays of unity and strength, and would use the Roman salute, or more specifically, a version of the salute that is closest to the Nazi version, with the arm in a straight line. Some contemporary observers were quick to note that Parindra was using this rather unusual salute, which set them apart from other Indonesian political parties at the time. While the Dutch National Socialist Movement (NSB; Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging) had an active branch in colonial Indonesia, its membership was predominantly European or of mixed Dutch-Indonesian (Eurasian) descent. It was rather striking to see Indonesians perform the Nazi salute. Newspaper articles from the period 1935-42 remark on Parindra’s bizarre practice, but it was only officially banned in 1941, as colonial authorities became increasingly uneasy about the prospects of a Japanese invasion. As early as 1937, members of Parindra – who claimed they did not adopt this form of greeting as a sign of fascist sympathies – used what they referred to as the groot saluut [great salute] or saluut tehormat [most honorable salute] during public meetings. Looking at the source material and the reports, one can hardly speak of shyness or an attempt at keeping this provocative practice a secret.

In 1941, Mohammad Husni Thamrin, the party’s most vociferous spokesman and a particularly active member of the Colonial Council, died of a severe illness, five days after he was put under house arrest by the Dutch colonial authorities. This punishment was imposed on Thamrin after allegations of him harboring pro-Japanese sympathies and planning to subvert Dutch colonial rule magnified to the point where they could no longer be ignored. Through his tragic death under forced arrest, Thamrin became a martyr not only for Parindra, but for Indonesian nationalism at large. As Jan Anne Jonkmann, president of the Volksraad from 1939 until 1942, put it in his memoirs: “Thamrin was buried like a prince. The interest and sympathy of the Indonesians were overwhelming.” 2 What was curious about this ceremony, however, was the way it was ‘staged’ as a ritual of national unity. One of many photos taken during this curiously militaristic ceremony shows the party’s leadership, headed by Soekardjo Wirjopranoto – an influential Parindrist and, like Thamrin, a member of the Colonial Council – marching through ranks of Surya Wirawan members performing the Nazi salute (see image 1). Additional newspaper material shows that not only the party’s youth organization, but also the upper ranks of the party used this particular salute deliberately.3

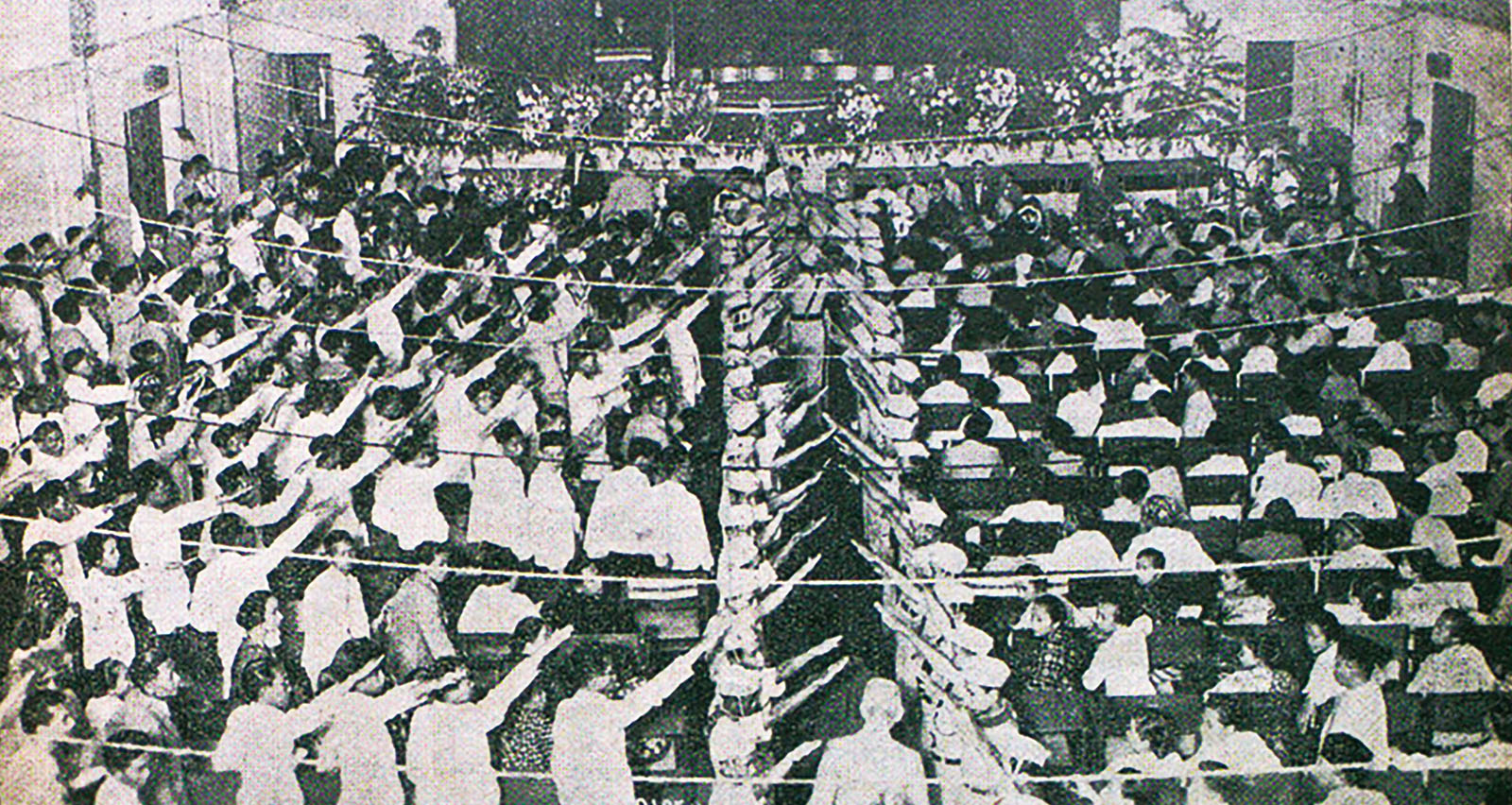

Photo of the second party congress of Partai Indonesia Raya (Parindra), 1939.

Two years earlier, in 1939, a similar bizarre large-scale ritual was performed during Parindra’s second party congress in Bandung (see image 2). Since a range of honorable Dutch guests, among them the Adviseur voor Inlandsche Zaken [Governor-General’s advisor for ‘native’ affairs], G.F. Pijper, attended the event, we can say with absolute certainty that this newly acquired ‘taste’ for fascist imagery did not go unnoticed. However, Dutch authorities did apparently not see any reason to be concerned. The official reports compiled by the colonial intelligence services, most notably the Politieke Inlichtingen Dienst [Political Intelligence Department], show no traces of concern about this fascist-style demeanor. The colonial press seemed to be more on the alert,4 but it was only in 1941 that the Dutch colonial government finally banned the salute in response to the German invasion of the Netherlands a year earlier. All along the way, Parindra maintained that the party “did not adopt [the salute] out of a particular sympathy for Hitler and his Nazis.” 5

Anticolonial nationalism, fascism, and the global context of the interwar period

What does the use of this salute tell us about the party’s attitude towards fascism? And what role did Parindra’s youth organization, Surya Wirawan, play in the party’s larger plans? As early as 1932, Soetomo voiced his opinion that the Indonesian nationalist movement had to “recruit ‘kasatrijas’ [ksatrya; knight] for the sacred and noble duty: the freedom of the fatherland and the people”.6 While Surya Wirawan emerged in the larger context of Robert Baden-Powell’s Boy Scout Movement, which turned into a global success story both in Europe and beyond, the innocent veneer of youth education could not hide the more radical ambitions that lurked beneath. As Pujo Semedi put it, the 1930s were a period of “scout radicalization” in Indonesia,7 and Surya Wirawan was at the forefront of this process. In 1936, Soetomo officially called for the transformation of Surya Wirawan into a militaristic youth organization modeled on the example of the scout group Nationale Jeugdstorm, established by the Dutch National Socialist Party.8 George L. Mosse, an eminent scholar of fascism, described the mobilization of (predominantly young) men in Fascist Italy in his book The Image of Man: “Mussolini's new man […] was to be inspired by the war experience, and indeed he lived in a state of permanent war. The constant wearing of uniforms, the marches, the emphasis on physical exercise, on virility, were part of the battle against the enemy.”9

Seen from that perspective, Surya Wirawan can be studied alongside other fascist-inspired anticolonial youth organizations, such as the so-called Blue Shirts in Egypt or China or Hindu-nationalist youth units that laid the foundation for today’s Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in India. After a series of (nonviolent) clashes with the authorities, the party had to officially admit that Surya Wirawan was no longer just about campfires, scouting, and singing songs. When Thamrin, during Parindra’s first party congress in 1937, declared that “Surya Wirawan is the ‘bibit’ [seed] that will make Parindra even stronger in the future”,10 he was hardly thinking of raising a new generation of devoted pacifists. And, in fact, it was only a year later that the party stated in public that “Surya Wirawan is not a regular scout organization, but a defense unit, based on the military model.”11

Another influential Parindrist, the journalist Soedarjo Tjokrosisworo, shared these ideas and espoused militaristic ideas shaped by the fascist ‘role-model’ in an article written for the Indonesian-language newspaper Soeara Oemoem. Complaining about the ‘lack of character’ of his fellow nationalists, he urged his compatriots to get inspired by European men of ‘great character’, including Hitler and Mussolini. After quoting one of Soetomo’s letters and praising the virtues of self-sacrifice, he ended his appeal to his fellow countrymen by citing a phrase by Baltus Wigersma, a Dutch National Socialist affiliated with the NSB: “There is no people corrupt enough to be totally devoid of national feelings.” 12 Apart from name-dropping fascist leaders and activists in newspaper articles and conferences, Tjokrosisworo became well-known as a gifted organizer for Parindra in Central Java, where he was heavily involved in shaping Surya Wirawan’s militaristic curriculum.

With the threat of a Japanese invasion looming larger and larger on the horizon, the colonial authorities slowly realized that Parindra and Surya Wirawan were far more than the ‘cooperating’ organizations they claimed to be. In 1941, even an author writing for Nederlandsch-Indië, the journal of the staunchly conservative Vaderlandsche Club, acknowledged that “Indonesians take European organizations which were instruments of Hitlerism as a role model. Indonesians learned about Nazism from the mouths of European ‘teachers’, hence they learned it from people who, from an Indonesian point of view, were highly respectable.” 13 This analysis is, in many respects, typical of the way Dutch observers in the 1930s and early 1940s looked at these trends among parties like Parindra.

An underestimated threat

Earlier in the 1930s, a Javanese, European-educated nobleman called Notonindito set up a short-lived party which he unambiguously named Partai Fascist Indonesia [Indonesian Fascist Party]. The very brief history of this party – apart from many important impulses that have opened my eyes to the possibility of a serious fascist ‘hype’ among certain strands of Indonesian nationalism – has been presented by Indonesian scholar Wilson in his book Orang dan Partai Nazi di Indonesia. Press coverage on Notonindito’s party shows that colonial observers did not take his party seriously for a variety of reasons. One of them was that fascism was considered to be too ‘European’ to take roots in Indonesia.

Only a few years later, we can observe similar reactions to Parindra and Surya Wirawan. Either their attempts to stage fascist-style parades and create an aura of grandeur to compensate for their lack of hands-on political bargaining power were ridiculed, or they were brushed aside in accordance with the biblical creed ‘forgive them, for they know not what they do’. Only on the verge of the Japanese invasion did contemporary observers, including the Dutch authorities, become more aware of the dangers that lay at the heart of Parindra’s self-aggrandizing, belligerent ideology. When the Japanese landed on Java in May 1942, they were eager to absorb Surya Wirawan into their military apparatus. Surya Wirawan was renamed Barisan Pemuda Asia Raya [Greater Asia Youth Corps] and trained to serve Japanese interests. However, Partai Indonesia Raya (Parindra), the party that was so eager to pave the way for Indonesia’s ‘liberation’ from Dutch colonial rule, was eventually banned as the Japanese military established total control over the archipelago. With the party banned, its militant youth organization, originally designed to fight for a ‘glorious Indonesia’, became the instrument of yet another foreign oppressor.

The ‘birth pangs’ of paramilitarism

Fascism, very much like the contemporary far-right, had a global appeal and took root in the most diverse geographical and sociocultural settings. While it was undeniably a child of the social and political dislocations in Europe after the First World War, its appeal – the promise of national regeneration through an explosive mixture of mass-militarization, authoritarian leadership, and mobilizing the public on a large scale – was truly global. In the last decade of Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia, some nationalists oscillating between traditionalism and modernism, such as Soetomo or Tjokrosisworo, were fascinated by the aura of Europe’s new ‘strongmen’. This sympathy for fascism rarely went hand in hand with a deep understanding of fascist ideologies in Europe. In fact, the writings and speeches of politicians and intellectuals associated with Parindra suggest that their knowledge of European fascism was rather shallow. Fascism was, therefore, not simply ‘transferred’ to Indonesia, but rather appropriated in a variety of ways. This perspective stresses the agency of anticolonial nationalists who sought to use fascist imagery and basic concepts to reinvigorate the nationalist struggle in Indonesia after the crushing defeat of the ‘non-cooperating movement’ under Sukarno in 1934. While parties like Parindra had little room for manoeuver under the vigilant eyes of the Dutch colonial authorities, its leadership drew from the ‘fascist repertoire’ in an attempt to boost the morale of party members and to create an aura of grandeur and success.

The last seven years of Indonesian nationalism under Dutch rule, from 1935 to 1942, were more about surviving than they were about thriving. If, to use the opening quote by George Orwell once more, the nationalist “persuades himself that [his side] is the strongest”, we have to understand that this self-persuasion could take on many forms. As the history of the interbellum shows, fascism was considered by a wide range of nationalists across the globe to be a viable path to energize ailing nationalist sentiments and to create cohesion. The trajectory of Indonesian paramilitarism during the decolonization war and the postcolonial period reveals that this problematic heritage of mass-militarism was to become a constant companion of Indonesian history up until this very day. The afterlife of Indonesian nationalists flirting with fascism deserves further scrutiny, as it was much more than just a by-product of Japanese indoctrination. Indonesia’s vibrant culture of paramilitarism was, in my opinion, the brainchild of nationalists trying to strike a new, perilous path during the bleak interwar years.

Yannick Lengkeek, University of St Andrews; winner of the IIAS National Master’s Thesis Prize in Asian Studies 2018. This article is based on his thesis “Neither Show nor Showdown: The 'Fascist Effect' and Cooperative Nationalism in Late Colonial Indonesia, 1935-1942”. yl217@st-andrews.ac.uk