The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Southeast Asia: History, Networks, and Identity

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival is a nine-day festival observed from the first to the ninth days of the ninth lunar month among the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. This festival honours the Nine Emperor Gods 九皇大帝 and their matriarch, the Dipper Mother 斗母, with devotees adopting a regimen of vegetarianism and abstinence, and dressing in white attire adorned with white headkerchiefs, yellow wristbands, and girdles [Fig. 1].

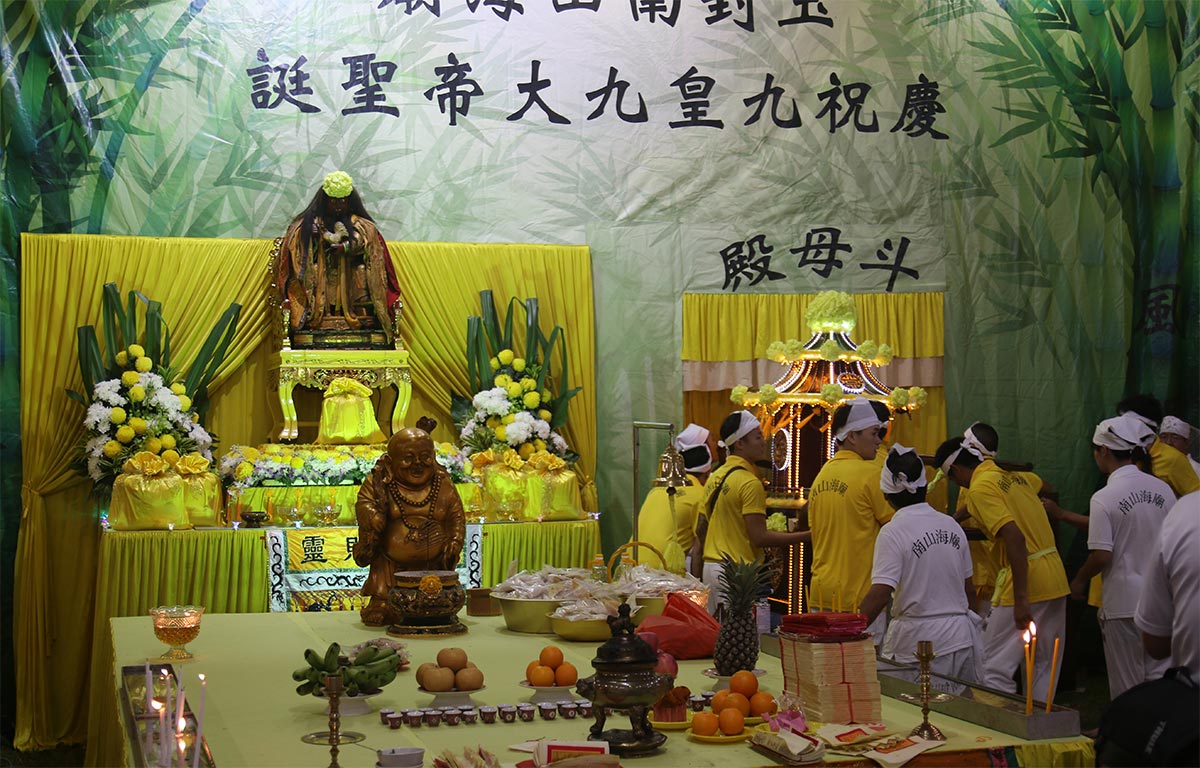

From the eighth lunar month onward, Nine Emperor Gods temples in Southeast Asia and their communities intensify preparations for the festival and begin the associated vegetarian diets. Temples raise nine lamps from bamboo sprigs or areca trees, a ritual performed either before or after receiving the deities. The festival officially begins with the arrival of the Nine Emperor Gods in the last week of the eighth lunar month. Devotees gather by the sea, rivers, lakes, or other water bodies connected to the sea to receive a consecrated incense censer. This censer is enshrined in a secret room known as the Inner Palace 内殿 for the duration of the festival [Fig. 2], concealed under a yellow cloth or covered palanquin whenever it is moved.

Fig. 2: The Nine Emperor Gods are invited to rest in a curtained Inner Palace erected by the devotees of the Nan Shan Hai Miao 南山海庙 in Singapore after their arrival at the festival site. (Photograph courtesy of the Nine Emperor Gods Project, 2016/2017)

During the festival, temples conduct various rituals to bless the community. On the concluding day, the ninth day of the ninth lunar month, the Nine Emperor Gods and their censers are sent off by the sea or other water body where they were earlier received. This marks the festival’s climax, with devotees flocking to temples and the seaside to bid farewell to the Nine Emperor Gods. For many temples, the festival officially ends with the lowering of the Nine Lamps in the late morning of the tenth day.

In recent decades, studies of Chinese societies in Southeast Asia have increasingly focused on popular Chinese religion. Previously, scholarship primarily examined major traditions like Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, or the cosmological and scriptural aspects of local practices linked to these religions. Since the post-war period, especially from the 1980s onwards, scholars have adopted anthropological approaches, situating religious practices within their social, cultural, economic, and political contexts. Taiwan and Chinese communities in Southeast Asia have become key focal points for these studies.

Scholarship on the Nine Emperor Gods Festival has grown in recent decades. Historically, in Southeast Asia, the festival has achieved a notable translocal and transregional profile among Chinese communities. Its scale, its duration, the restrictions on devotees’ daily lives, and the unique colours and rituals have made it a significant fixture in the traditional religious life of overseas communities [Fig. 3]. Our research project places the festival and its elements within their broader historical context in China and Southeast Asia, as well as the history of Chinese migration between regions. Additionally, we examine the festival’s rituals, representations, material culture, symbolisms, and belief systems within the long-term history of Chinese culture and traditions. 1

Fig. 3: Devotees, palanquin bearers, and leaders of Leong Nam Temple 龙南殿 paying their respects before they send off the Nine Emperor Gods on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month. (Photograph courtesy of the Nine Emperor Gods Project, 2016/2017)

Although the festival has been observed in China since the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), the version observed by overseas Chinese communities from the latter half of the 19th century onwards, and especially in Southeast Asia, is distinct in its dress code, rituals, and purpose. This article examines how the festival’s transformation reflects the histories, contexts, and memories of southern Chinese migration to Southeast Asia and the historical evolution of the societies, cultures, and traditions in the region over the past two centuries.

The Nine Emperor Gods religious networks in 19th-century Southeast Asia

The origins of the Nine Emperor Gods Festival and its worship are still unclear, although it is generally agreed that two of the earliest festival centres in Southeast Asia were the Kathu Shrine內杼斗母宮 in Phuket, Thailand, and the Hong Kong Street Dou Mu Gong 香港斗母宫on Penang Island in Malaysia, during the 19th century. In Phuket, the festival was introduced by a visiting opera troupe that advised the Fujianese labourers working in the tin mines to observe a vegetarian diet and celebrate the festival to overcome a plague. 2

On Penang Island, Fujianese sailors enshrined incense ashes dedicated to the Nine Emperor Gods with Qiu [Khoo] Macheng 邱妈诚 (1784-1841), along with a religious scripture bearing the deities’ names. Khoo’s descendants continue to run the temple to this day [Fig. 4]. 3 From the Hong Kong Street Dou Mu Gong, incense ashes were brought to Singapore by the businessman Ong Choo Kee 王珠玑, who initially enshrined them within his home on Lim Loh Village in 1902. In 1921, the ashes were moved to a permanent location at the Hougang Tou Mu Kung 后港斗母宫 on Upper Serangoon Road. 4

Fig. 4: The interior of the Hong Kong Street Dou Mu Gong. Note the pair of couplets that are predominantly made up of the characters “sun 日” and “moon 月.” (Photograph by Esmond Soh, 2022)

From the Kathu Shrine in Phuket, incense ashes dedicated to the Nine Emperor Gods spread to other parts of the region, notably Ampang in Selangor and Taiping in Perak, where significant religious centres dedicated to the Nine Emperor Gods were established. The Ampang Nan Tian Gong 南天宫 (founded circa. 1862) became an important hub for the Nine Emperor Gods worship, aided significantly by travellers who carried incense ashes or sacred objects from the temple to other parts of the region. 5 This led to the founding of Hong San Temple 凤山宫 in Singapore (circa. 1904), as well as the Pak Tiam Keong 马六甲北添宫 in Malacca and the Shin Sen Keng 神仙宫 in Singapore (both established in the 1920s). Others travelled to Ampang to receive the Nine Emperor Gods incense ashes, such as the case of Sam Siang Keng in Johor Bahru 柔佛三善宫, which began observing the festival from the 1950s onward.

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival and the political economy of Southeast Asia

A common thread among the earliest religious centres of the Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Southeast Asia, established from the early to late 19th century, was their close association with the extractive economies that characterised the region’s pre-colonial and colonial political economy. Tin played a significant role in this economy, serving as a major source of commerce managed and contested by Chinese businessmen. Phuket and Penang were deeply intertwined in this manner, with tin harvested from Phuket and southern Siam and then refined for sale to the world via Penang. 6

Interestingly, and perhaps not coincidentally, business holdings were established on both Penang and Phuket by the Fujianese mutual aid organisation known as the Kian Teik Tong 建德堂 [Fig. 5]. This organisation wielded considerable influence in the management of labour and political affairs in the region before its eventual disbandment by the British Societies Act of 1889 in colonial Malaya. The Kian Teik Tong’s headquarters at Armenian Street on Penang Island not only served as a temporary site for the Nine Emperor Gods worship under the supervision of the Khoo family but also facilitated labour and tin exports from Phuket. 7

Fig. 5: Titular plaque of the Kian Teik Tong currently displayed on the second floor of the Poh Hock Seah 宝福社, located on Armenian Street, Penang. (Photograph by Esmond Soh, 2022)

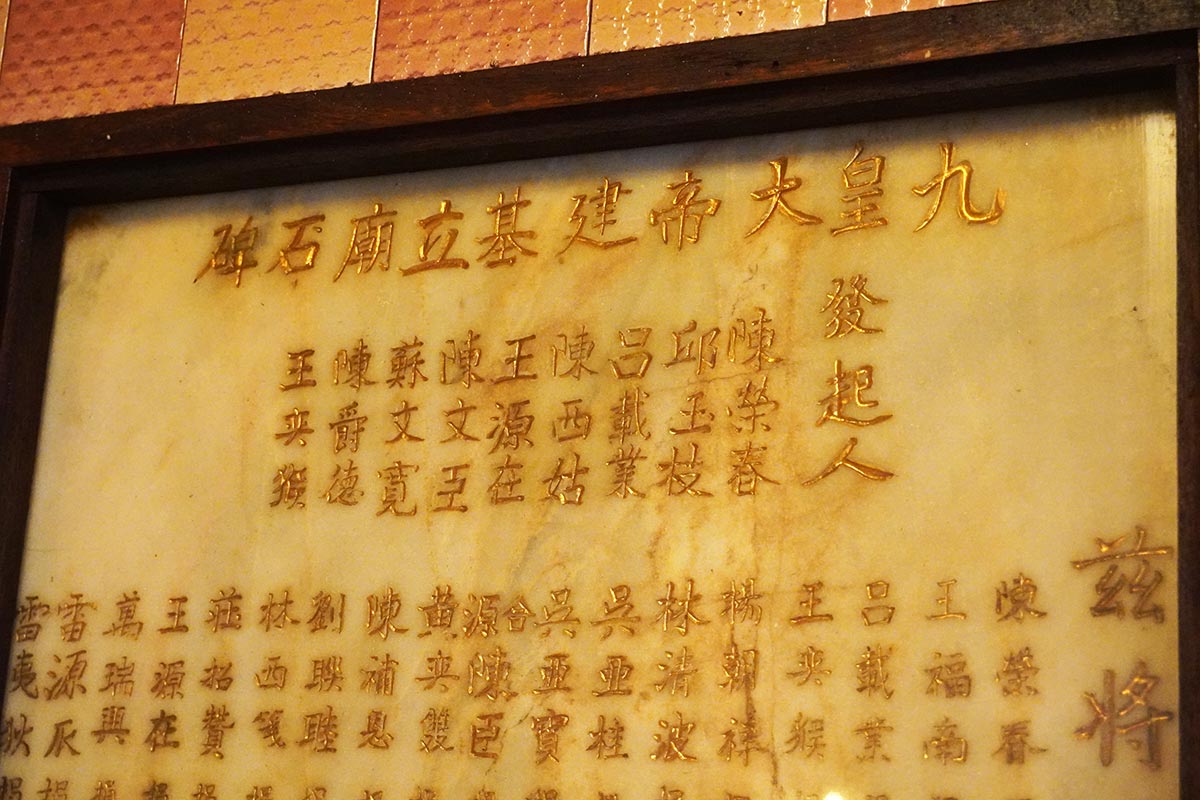

This pattern was also evident in Ampang, whose road connection to the city of Kuala Lumpur was developed by Kapitan Yap Ah Loy (1837-1885) and predominantly populated by Hakka tin-miners, though the temple also had a strong Anxi (Fujianese) presence during the 19th century. 8 5 (2017): 131-133.] Similarly, Taiping in Perak emerged as a centre for financing and processing tin with the discovery of tin deposits in the Larut region. The Nine Emperor Gods worship began there with the enshrinement of incense ashes from the Kathu Shrine by Wang Yiyu 王奕鱼.Wang’s cousin Yihou 王奕猴 later travelled to Ipoh, which by the 1880s had become a prosperous city due to tin harvesting from the surrounding Kinta River. There, he founded another Nine Emperor Gods temple in 1896 [Fig. 6]. 9 Thus, the initial genesis of these Nine Emperor Gods temples was closely tied to Southeast Asia’s political economy and could not be separated from their initial popularity and appeal among the labourers and financiers who lived and worked in these locations.

Fig. 6: Commemorative stelae erected to mark the construction of the Ipoh Tow Boh Keong in 1916. The first name from the left is Wang Yihou, the founder of the temple. (Photograph by Esmond Soh, 2023)

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival and Chinese identities in Southeast Asia

There are numerous unique accounts of the Nine Emperor Gods that have proliferated in Southeast Asia, in addition to East Asian traditions, where the deities are conventionally (but not always) conceived as stars. They represent different manifestations and memories of the Nine Emperor Gods in different historical periods and geographical regions, and their significance for different Chinese communities. Despite their differences, many of these accounts share common tropes. We will briefly summarise a few of the most prominent ones below.

In two Nanyang Siang Pau reports from after the Japanese Occupation of Malaya (1939-1945), the Nine Emperor Gods are depicted as nine brothers who defied Qin Shihuang (259-210 BCE). The emperor enlisted a ritual master who beheaded them and sealed their bodies in a vessel set adrift at sea. A fisherman later released their remains, and the brothers reappeared before the Qin emperor. Terrified, Qin placated them by granting them the title ‘Emperor Gods’ 皇爷神 and building temples where their images were absent due to their decapitation. 10 ,” 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, October 18, 1947, 7; 悦民 Yuemin, “九皇爺的來歷是反對專制魔王的民族英雄 (The Nine Emperor Gods were originally National Heroes who opposed an Autocratic King),” 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, October 26, 1949, 7.]

A separate account of the Nine Emperor Gods’ origins in Southeast Asia emerged 50 years later in a commemorative volume by the Ampang Nan Tian Gong. During the Qing invasion of China, nine pro-Ming martyrs were beheaded, and their heads were sealed in a vessel set adrift at sea. Fishermen in Fujian found the vessel, leading to widespread grief. A grand funeral was held, with mourners donning white clothing [Fig. 7]. To avoid Qing suspicion, these martyrs were collectively honoured as the ‘Nine Emperor Gods.’ During the festival, the temples’ Inner Palace was completely out of bounds, as Ming loyalists used the room as a meeting-place to plot the overthrow of the Qing dynasty. 11

Fig. 7: Leaders of the Ampang Nan Tian Gong await the departure of the Nine Emperor Gods. Note the dress code of white clothing and white headkerchiefs, and the concealed entrance of the Inner Palace. (Photograph by Esmond Soh, October 2023)

The Nine Emperor Gods may also refer to Robin Hood-like pirates, who became deified for their heroic deeds. Kim Edwards recounts a Mr. Foo’s version of the Nine Emperor Gods’ origin in Kuantan, Pahang. Nine brothers in Qing China, who stole from wealthy foreigners to aid their neighbours, were beheaded by Qing forces. Later, nine incense censers drifted ashore, leading to their veneration in a nine-day festival. 12

Another variation identifies the Nine Emperor God as a single individual during the Ming dynasty. 13 In 1979, a journalist authored an article identifying the Nine Emperor God as Prince Lu 鲁王, the regent of the Southern Ming (ca. 1644-1662) from 1645-1651. When Prince Lu travelled south to join Zheng Chenggong’s 郑成功 (1624-1662) campaign against the Manchu invaders, Zheng was said to have drowned him in cold blood. Witnesses to Zheng’s treachery fled to Southeast Asia, where they honoured Prince Lu as the Nine Emperor God. The absence of images of the deity is attributed to his body being submerged, leading to representation by a spirit tablet. During the festival, a censer representing the deity is believed to rise from the ocean and is received by devotees on the shore. 14

Interestingly, contemporaneous accounts suggest the ‘Nine Emperor God’ was a coded name for Zheng Chenggong himself. In these retellings, Zheng visited Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in Fujian, aided by Shaolin monks to coordinate his forces against the Qing dynasty. As a wanted man, he was shielded by a canopy upon arrival and escorted to a temple’s secret room, where he planned his campaigns against the Qing. This room inspired the Inner Palaces in Nine Emperor Gods temples. 15

The prominence of these diverse stories indicates three key points. Firstly, they provide an aetiology of the festival’s unique ritual traditions and why the Nine Emperor Gods manifested in the form of a censer that must be enshrined within an Inner Palace. Many of these older Nine Emperor Gods temples in Southeast Asia lack imagery of the Nine Emperor Gods. Unlike most Chinese religious followings, where deities are represented by physical images or paintings, many Nine Emperor Gods temples venerate the deities through a spirit tablet, or in the case of the Ampang Nan Tian Gong, a piece of paper inscribed with the words ‘Nine Emperor Gods’ in the temple’s Inner Palace. Some temples do not even have a permanent spirit tablet, or characters dedicated to these deities for devotees to worship. Instead, they maintain a permanently enclosed Inner Palace within their grounds, which can only be worshipped by devotees kneeling at its threshold. This practice has been rationalised by several of the accounts mentioned above, whether it is due to the deities’ decapitation, their bodies being lost at sea, or the need to maintain their anonymised identities in the face of prying eyes from the Qing authorities.

The Ampang Nan Tian Gong’s version also accounts for why the festival resembles a funeral, with its white dress code, including the covering of the head in white (the de facto colour of mourning and death). In this regard, because red is a celebratory colour, this may account for why Nine Emperor Gods temples prefer the yellow colour scheme. Additionally, ‘yellow’ 黄serves as a homonym for ‘emperor’ 皇 [Figs. 8-9]. These accounts sought to explain why the festival has features that make it unique from other Chinese deity festivals.

Fig. 8-9: The premises of the Hougang Tou Mu Kung, Singapore, are decked with yellow canvas, awnings, lanterns, candles, and votive banners during the Nine Emperor Gods Festival. (Photograph courtesy of the Nine Emperor Gods Project, 2017)

Secondly, many of these stories are connected with anti-Qing and Ming loyalist tropes, which overlap with practices of various mutual aid societies in Southeast Asia. These societies, prevalent among the Chinese in Southeast Asia, predicated their rituals, iconographies, and practices somewhat on the collective ideal of overthrowing the Manchus and restoring the last Ming royal descendant to the throne. Indeed, a special set of couplets commonly displayed in many Nine Emperor Gods temples consists of four consecutive characters made up of the characters ‘sun’ and ‘moon’; when placed together, they spell out the character ‘Ming’ – a hidden reference to the Ming dynasty and to loyalist projects for its restoration [Fig. 10].

Fig. 10: Threshold of the Choa Chu Kang Tao Bu Keng, Singapore. Note the pair of couplets that are predominantly made up of the characters “sun 日” and “moon 月.” (Photograph courtesy of the Nine Emperor Gods Project, 2017)

Finally, the persistence of these ritual traditions indicates that localised religious practices remain a powerful source of the festival’s longevity and association with Chinese identities in the context of Southeast Asia and southeastern China. Their repetition suggests that the identities of these Nine Emperor Gods temples, and observers’ understanding of the festival and who the Nine Emperor Gods are, are predicated upon the historical experiences, memories, and contemporary situations of the wider Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, as well as their connections to and interactions with historical and contemporary China.

Conclusion

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Southeast Asia serves as a poignant reflection of the Chinese communities’ cultural adaptation and resilience, and of the historical imaginaries and memories connecting those communities to China and especially their ancestral regions in southern China. Rooted in rich historical narratives and deeply intertwined with the region’s political economy, the festival’s unique rituals and traditions underscore a collective identity shaped by a blend of reverence, resistance, and remembrance. The persistence and evolution of these practices highlight the enduring significance of localised religious traditions in maintaining cultural continuities and identities. By honouring the Nine Emperor Gods, the overseas Chinese reaffirm their historical ties and shared heritage, including cultural and historical connections to China, while simultaneously asserting a distinct identity within the diverse sociocultural landscape of Southeast Asia.

Esmond Chuah Meng Soh is a PhD student with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. Email: sohcmesmond@gmail.com

Koh Keng is Assistant Professor in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Email: kohkw@ntu.edu.sg