Nigerian medicine entrepreneurs. Field encounters in Guangzhou

The growing presence of Africans in China has received much scholarly attention, with most agreeing that the city of Guangzhou attracts the greatest number of African migrants.1 Despite the unresolved debate about the size of this population, there is nonetheless the shared view that Nigerians are in the majority.2 According to the Nigerian Consulate in Guangzhou, there were approximately 70,000 short visits from Nigeria to China in 2014, and a slightly higher number in 2015. Close to 400 Nigerians had a residence permit in Guangzhou in 2017. However, the official figure is most likely an underestimation because the vast majority of Nigerians residing in the city are undocumented, and many do not register with the Nigerian Consulate.

This article, previously presented at the Africa-Asia conference in Dar es Salaam, describes my field encounters with two undocumented Nigerian medicine entrepreneurs in China, which took place during my doctoral research. Their experiences as medicine traders in Guangzhou is uniquely useful in providing a lens through which to observe how migrant entrepreneurship is being deployed to survive and negotiate the intersecting problems of unemployment and healthcare inaccessibility in China.

Healthcare inaccessibility facing Africans

African migrants experience poor access to healthcare services in Guangzhou. The barriers they encounter have institutional, economic, social and cultural dimensions. Some empirical studies documented that racism and visa issues are involved.3 Other scholars explored the problem of distrust that Africans have for Chinese physicians.4 In comparison with internal Chinese migrants, Africans in Guangzhou experience more problems, including longer waiting hours, high cost of care, poor treatment and a lack of comfortability with healthcare workers.5 Extant studies suggest that in response to the problems faced African migrants resort to strategies such as self-medication, obtaining healthcare from in-training African doctors, recruiting the help of friends with Chinese language competency when visiting the hospital or merely seeking medical attention in the country of origin or a third country.6

In reaction to the poor accessibility to healthcare, two Nigerian migrants established a medicine trade business. With claims that they were answering a ‘divine call’ to help co-migrants solve, manage and cope with health challenges in the Chinese city, their endeavour was also clearly an opportunity to make a living and/or survive in a context where employment opportunities are limited.

Encountering Nigerian medicine traders

The first time I met Mr. A., a 42-year-old Nigerian, it was at Guangyuan Xi Lu (market), where he was delivering a medicinal concoction to Nigerians late at night, for the price of RMB 20 (USD2.89) per small cup. In many major markets and motor parks in Nigerian cities, the sale of this medicinal concoction, known locally as paraga, is commonplace.7 However, I did not expect to find the same practice in faraway China. I introduced myself and Mr. A agreed to meet me later, at some location outside Yuexiu District, which is when I also met Mr. B. for the first time. Unlike Mr. A., Mr. B. trades in a wide array of Nigeria-imported daily needs goods and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, alongside herbal concoctions. Mr. B. dispenses herbal mixtures from large bottles that contain roots, leaves and fruits. Some of the mixtures, which Mr. B called ‘wash’ because of their potency to cure “everything unhealthy inside the human body”, were laced with alcohol.

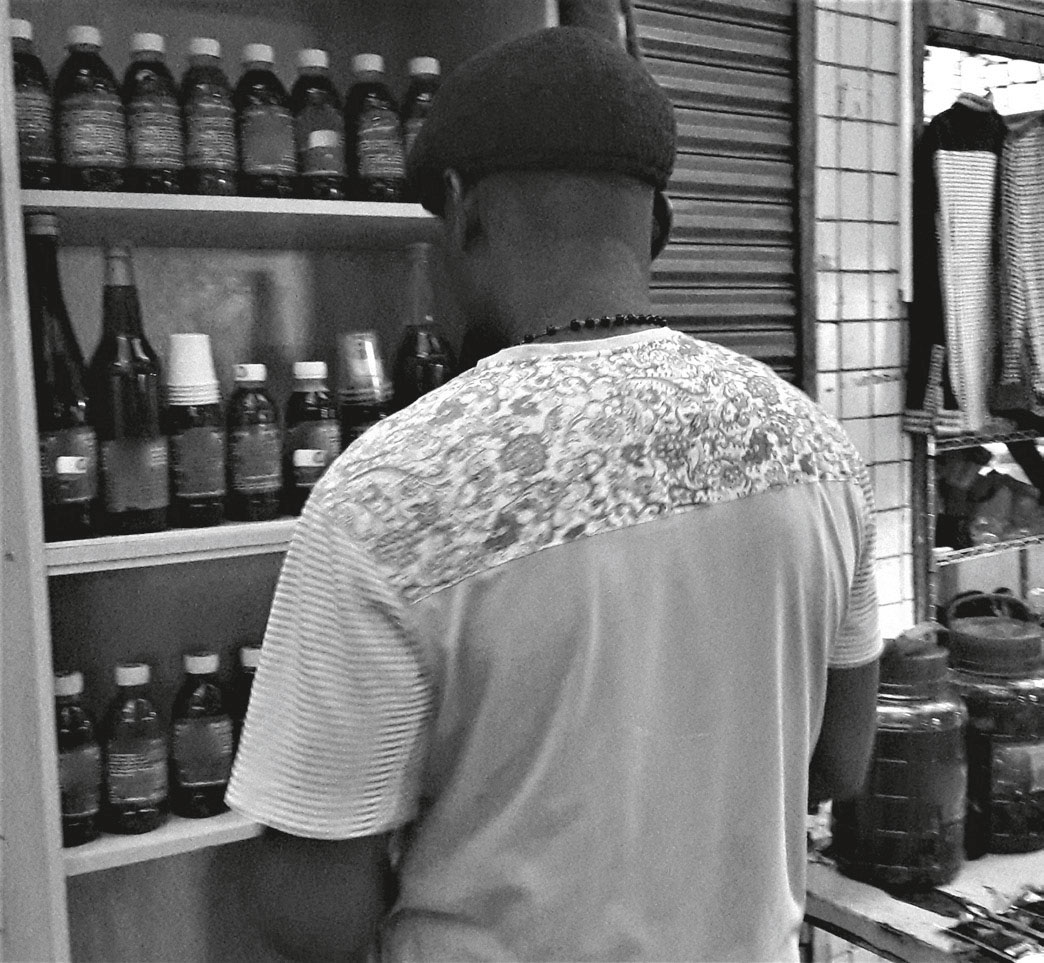

Mr A stands by his medicine display shelf.

Along with many other undocumented Nigerians in the city, both medicine traders established a base outside Guangyuan Xi Lu because of the deepening intensity of police crackdowns on undocumented foreigners in African-dominated sections of Guangzhou. According to the two medicine traders, it has become “less safe to live and work” in Baiyun and Yuexiu Districts.

‘Divine call’, livelihood and modes of medicine trade

Both Mr. A. and Mr. B. traced their involvement in the medicine trade to a prophesy that a Nigerian ‘Man of God’ (one of “the most popular priest in Nigeria”) had delivered to both of them. They both interpreted the prophesies as ‘divine calls’ meant to redirect them towards the medicine trade business. Concealed beneath the divine calls, however, were other push factors into medicine trade. One, both of them have previously failed to establish successful businesses, including in transnational trade, which is a major livelihood path for many Africans in Guangzhou. Two, they identified a gap to fill with regard to the healthcare situation of Africans in Guangzhou. They recognised a lack of culturally appropriate healthcare services in the city and felt that Nigerians were experiencing poor health as a result. Besides, they believed that the cost of healthcare was prohibitive for many Nigerians, so a business that provided cheaper alternatives became necessary.

Mr. A. and Mr. B. operate in both similar and different ways. Two main points of similarities: reliance on ‘flyers’ and client selectivity. Both entrepreneurs rely on ‘flyers’, circular migrants who make regular trips between Nigerian and China, transporting ingredients and other goods needed to sustain the medicine business in Guangzhou. On client selectivity, Nigerians are their main customers, but they also service other African migrants. Chinese people are excluded from their clientele, as selling to them could lead to trouble. Avoiding trouble is crucial to self-preservation for an undocumented migrant.

Their modes of practice also differ in many ways. Firstly, as mentioned before, Mr. A. only sells traditional medicines (single item model), while Mr. B. incorporates OTC drugs and daily needs goods (plural item model). Secondly, the previous experience they bring to the medicine trade, differs quite a bit. Before arriving in China, Mr. A. had sold traditional medicines in Nigeria and had learned about herbs from his grandmother whom he claimed was a healer. Conversely, Mr. B. brought no prior knowledge of herbs or healing to his medicine trade. Thirdly, unlike Mr. B. who relies on instinct to give prescriptions, Mr. A. emphasises diagnosis before prescription. As I observed while at his shop, Mr. A. asks diagnostic questions and sometimes even directs clients to go for laboratory tests to ascertain the problem. Insisting on a diagnosis is how he legitimises himself as a professional. Finally, Mr. B. usually offers a one-off service, where clients buy whatever drug they need in normal exchange relations. Mr. A.’s approach, on the other hand, is more personalised and intimate. Depending on the ailment and the amount involved in the curing process, Mr. A. may begin by referring a client to the medical lab for a test, recruit his Chinese girlfriend to translate the lab report, then proceed to his private in-house chapel to pray over medicinal concoction, using Christian and African traditional symbols and materials. He might take the same concoction to the famous Sacred Heart Catholic church in Yide Lu for a special prayer, after which he delivers it to his client. This is clearly a more complex modality of healing practice when compared with the one-off approach of Mr. B.

Conclusion

The involvement of African migrants in trade-related activities is preeminent in ‘Africans in China’ studies. In Guangzhou specifically, the range of livelihoods that characterise the entrepreneurial engagements of Africans is not well known. Beyond the sphere of trade in, and exportation of, manufactured commodities, scholars have not beamed a spotlight on the medicine trade that caters to the needs of fellow migrants. This is what I have attempted with the two medicine traders that I met in Guangzhou, while researching the settlement experiences of Nigerians in the city.

More research should be done to understand the extent and context of African migrant medicine trade in China. Considering how the instrumentalisation of religion shows a pathway to entrepreneurial success, we have an opportunity to explore the concept of ‘health entrepreneurship’ in the transnational moment. The prospect of linking migrant health entrepreneurship to the issue of syncretic healing is also enormous. Overall, despite the structural and legal impediments they experience, the stories of Nigerian medicine entrepreneurs demonstrate the willingness of undocumented African migrants in China to integrate in their adopted community, while also improving their socioeconomic situation.

Kudus Oluwatoyin Adebayo, Department of Sociology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria oluwatoyinkudus@gmail.com

The doctoral research on which this article is based was supported by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA), the African Humanities Program (Dissertation Completion Fellowship), and the Small Grants for Thesis Writing awarded by the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA). However, the statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. Many thanks go to Eunice Kilonzo and Tade Oludayo for reviewing versions of this essay.