The military's role in Indonesia's democracy. Misguided perception?

After the political reforms in the late 1990s, the Indonesian military notably started to redefine its role in non-defense-related activities. Some active generals began to express their aspirations to participate in the non-military realm of politics, which generally involves less transparency, accountability and oversight than the military institution. The question arises, to what extent can the Indonesian democratic system control the undemocratic features displayed by the military and its officers?

Shortly after the presidential election results were announced by the Indonesian electoral commission (KPU) on 21 May 2019, there was massive mobilization to reject the official outcome. Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo’s victory was challenged not only by his opponent Prabowo Subianto, a former general and son-in-law of long-time dictator Suharto, but also by Subianto’s supporters or so-called sympathizers who come mostly from various Islamic groups. The protest turned to riots in Jakarta on 22 and 23 May. The Indonesian police arrested a few political figures for their alleged connection to the riots and suspected implication in treasonous activities against the current administration.1 The arrests included two former army generals: Soenarko, a former special forces commander, and Kivlan Zein, a former commander of the army strategic command. A number of (former) army officers, including Ryamizad Ryacudu, an Indonesian defense minister, expressed their disagreement with the arrests. Soenarko was later released from detention with a guarantee from an Indonesian military commander and a (retired) senior minister. The release reflects a privilege owned by the military and its former officers in Indonesia. Jokowi himself, as the reelected president, determined the importance of calming down the military by holding a closed meeting with a number of generals.

In modern Indonesian history, the Indonesian military (TNI) has never been far removed from the country's political crises, including the 2019 post-election riots. It is not only an Islamic political identity that has shaped the country's narrative in the last decade, as argued by certain scholars,2 but also the military’s politics, which still find its ground long after the downfall of Suharto's regime. The question is not whether there is a re-emergence of the New Order political model, in which the military actively pursued formal or institutional political roles, as highlighted by political commentators in 2015.3 The perception is that the military in fact never abandoned this role in democratic Indonesia. The reforms, which dismantled active political roles of the military, were neither able to curb TNI’s aspirations to meddle in civilian political and social life, nor to assure that TNI carry out its professional duty in defense-related matters and respect human rights in conflict areas.

Democracy for an undemocratic institution

The democratic system does not merely require military subordination to civilian authority, it must also assure that the military upholds democratic rules that emphasize an apolitical stance, transparency and accountability. By law (No. 34/2004), TNI officers are prohibited from involvement in political activities unless they retire from active service. However, this requirement does not stop TNI political aspirations, since there are no internal or external instruments to control such ambitions.4 The situation is reminiscent of the authoritarian regime under Suharto.

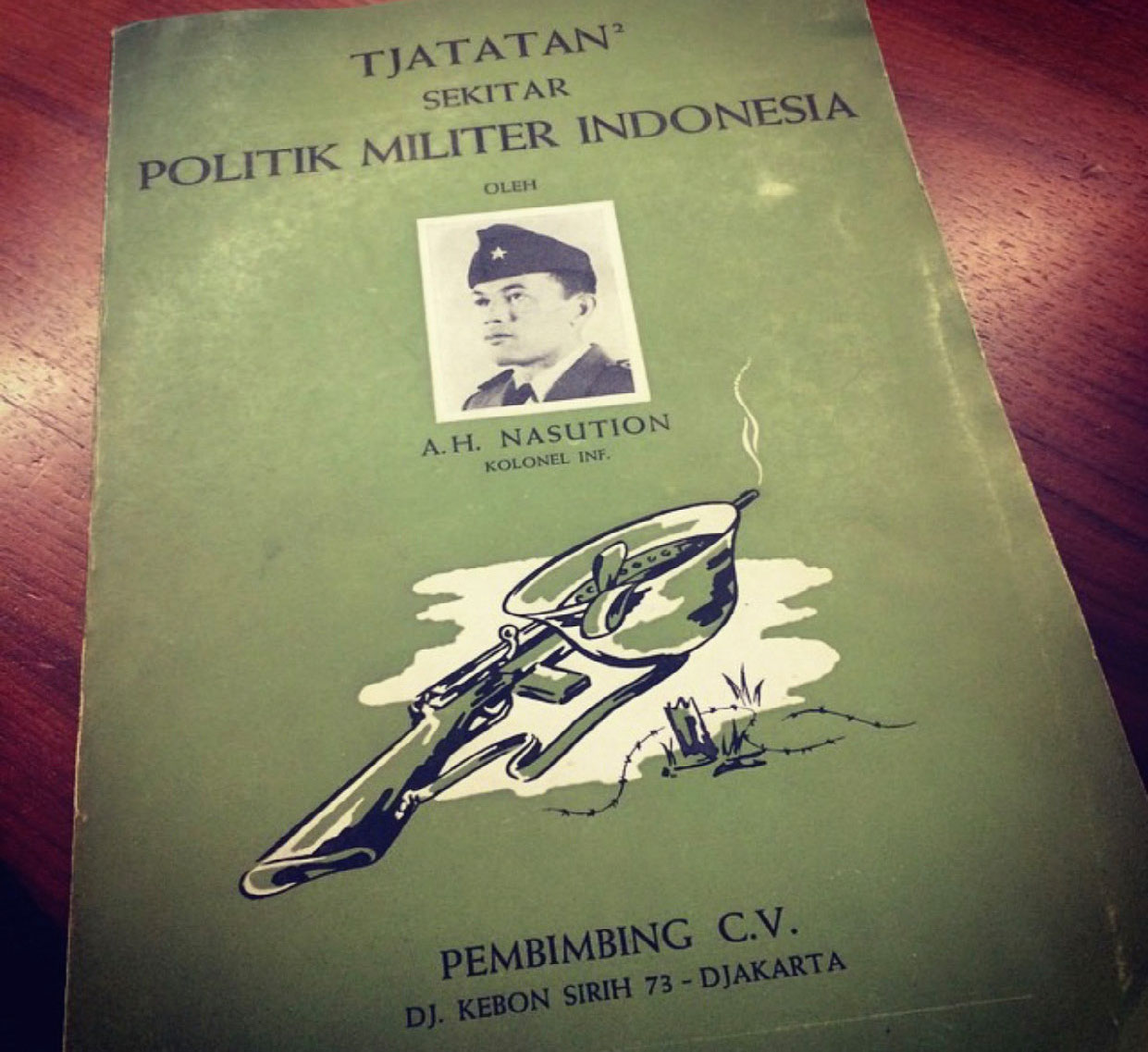

Copy of the first book on Indonesian Military Politics written by Abdul Haris Nasution, a former army general and a defense minister [Tjatatan-Tjatatan Sekitar Politik Militer Indonesia, Jakarta: Pembimbing, 1955].

The democratic transition, which was also marked by internal reforms of the TNI along with an economic crisis and student protests in the waning days of Suharto's period, remains only partially accomplished. The perception that the TNI has completed its reform by demolishing its political and social involvements, focusing solely on national defense, has turned out to be misguided. In the late 1990s, internal reforms were demanded under international and national pressure, and the military could no longer count on the weakened Suharto regime for protection. As a result, the military had no choice but to pursue a democratic agenda.

However, once the crisis and transition passed, the military reconsolidated its power by gradually meddling in civilian life, from political to social spheres. In the democratic era, when some active high-ranking officers publicly expressed their political aspirations, even the TNI and several ministerial and state agencies signed agreements in which they assigned the officers not only to defense but also to non-defense tasks, such as farming, forestry, and education. Hundreds of ‘underemployed’ senior officers continue to be installed in a broad range of civilian ministerial and institutions. For instance, the recent initiative by the Indonesian Ministry for Energy and Mineral Resources to appoint a mid-ranking Air Force officer as their director of disciplinary affairs, exhibits not only the increasing role of military in civilian affairs, but also shows the submissive attitude of civilians.5

As for the issues of human rights and military businesses,6 transparency and accountability are critical. Unfortunately though, the military avoids holding accountable those officers who have allegedly abused their power. Some who have been implicated in past cases have even received promotions.7 Ironically, the Indonesian public in general, and even parliament, have displayed no interest in pushing forward the unfinished military reform agenda as a public discourse.

Papua as the remaining battlefield

Another military reform agenda concerns the military’s presence in West Papua. Over the years, the TNI and its security approach have created more problems than solutions, particularly related to the human rights of indigenous Papuans. An Amnesty International report documented 69 cases of suspected unlawful killings, of mostly indigenous Papuans, by security officers between January 2010 and February 2018.8 In addition, there has been no legal follow-up of three prominent human rights cases in Papua in which the military was involved: the Wasior incident in 2001, the Wamena incident in 2003, and the Paniai shooting in 2014. All of which reflect how the military continues to act with impunity in Papua.

The recent demonstrations and riots in Papua display the excessive use of force by the military and the police in dealing with the Papuans and their long-running protests towards the central government.9 The massive deployment of military personnel has resulted in collective trauma and memory of violence that remind the Papuans of past suffering. Such deployment has been undertaken without clear oversight from the executive and legislative bodies as mandated by the law No.34/2004. The use of live ammunition by security forces has led to a large (and increasing) number of civilian deaths of indigenous Papuans. The heavy-handed military response to peaceful protests intimidates Papuan society, as seen recently in Jayapura and Wamena on 23 September 2019. The result was more turmoil and violence.

Moreover, the ongoing armed conflict between the Indonesian military and the pro-independence group in Papua’s Nduga reflects the failure of the military presence to provide basic security in Indonesia’s easternmost area. A series of counterinsurgency operations in Papua since the area became part of Indonesia in 1969 have drawn a public backlash from indigenous Papuans. As I observed during fieldwork in Papua, memories of suffering endure for the majority of indigenous Papuans, particularly those in the highlands where many of those operations took place, including the home of the now displaced Nduga.

The key to conducting a successful counterinsurgency operation is not to control the area with a heavy hand, but to win the hearts and minds of local indigenous people. Such a strategy depends on popular consent from locals to underpin joint operations to defeat local insurgents. However, the counterinsurgency operations led by the Indonesian military and police, to hunt the pro-independence fighters, have created a backlash rather than local support. Locals resist military authority, disobey curfews, and some even rejected the basic supplies distributed by security officers in the early days of the conflict in December 2018. The military reform has clearly failed to take root in Papua.

Jeopardizing democratic principles

All in all, the role of the Indonesian military in their democratic country raises serious concerns. Much of its internal reform agenda, such as focusing on defense-related tasks, upholding transparency and accountability, and carrying out its professional duty in conflict areas, is not comprehensively pursued by civilian authorities. In addition, the lack of institutional and external controls to contain the political aspirations of senior military officers jeopardizes democratic principles.10 Sadly, Jokowi will most likely show no political will to resume the stalled military reform, as, in his second term, he still relies heavily on retired generals. And Indonesian democracy will still strive not to avert the reemergence of the New Order, but to force the military, an undemocratic institution, to follow democratic rules and principles.

Hipolitus Yolisandry Ringgi Wangge, researcher at the Marthinus Academy Jakarta, conducted fieldwork in December 2018 to August 2019 in Papua. hipolitusringgi@gmail.com