Meritocracy in Asia: Beliefs in Its Ideals and Reality, and Life Satisfaction

How is belief in meritocracy related to satisfaction with life? If one sympathizes with the meritocratic principle that prizes should be distributed according to talents and efforts, but also believes that society does not adhere to this principle in practice, then how does this influence evaluations of one’s current life? This piece explores this question using the results of the “Social Values Survey in Asian Cities.”

Two keywords that have been the subject of heated debate in Korean society over the past decade are “fairness” and “meritocracy,” a result of the younger generation speaking out against society’s existing compensation structure. This trend is reflected in the responses to questions regarding meritocracy and life satisfaction in the “Social Values Survey in Asian Cities.” The rate of fairness being mentioned as a value to be pursued was low in all societies, but ten percent of respondents from Seoul chose fairness as the most important value. On the other hand, five percent of respondents from Tokyo and less than three percent of respondents from other cities mentioned fairness as the most important value that society should pursue.

How, then, does the tendency to pursue fairness based on meritocracy relate to an individual’s degree of satisfaction with life? The questions regarding meritocracy that were asked as part of the “Social Values Survey in Asian Cities” consisted of four questions about whether one agreed with the principles of meritocracy, and an additional four questions about whether one believed that her society operated according to those principles of meritocracy. The first four questions concern the ideals of meritocracy; the other four questions measure the respondents’ belief in the reality of meritocracy. The survey questions were designed based on the hypothesis that the greater the difference between one’s ideal of meritocracy and reality, the lower her life satisfaction would be. The analysis presented in this article focuses on the results of responses from a total of nine cities based in Asia, including four countries in Northeast Asia (Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and China), four countries in Southeast Asia (Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam), and one country in South Asia (India).

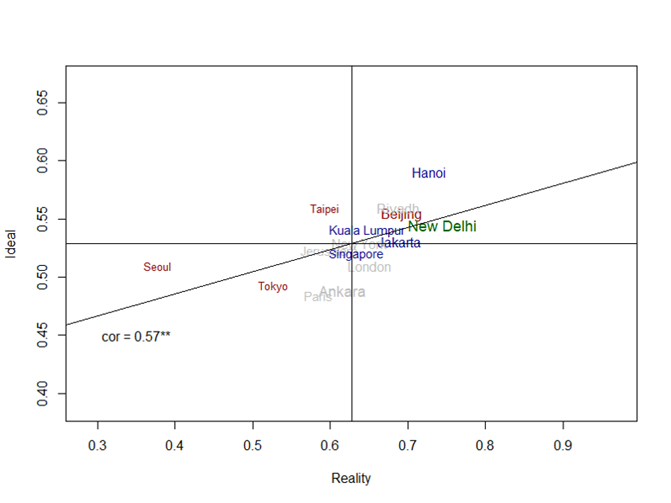

First, Figure 1 shows the distribution of the average ideal (Y-axis) and reality (X-axis) of meritocracy, as well as the average degree of life satisfaction by city (font size). The tendency to believe that meritocracy is desirable was highest in Hanoi, but it was surprisingly low in Seoul and Tokyo. The tendency to believe that society operates according to meritocracy was high in New Delhi and Hanoi, and it was low in Seoul and Tokyo. In particular, Seoul showed a much lower score than other cities in this regard. Life satisfaction by city was highest in the following order: New Delhi, Beijing, Jakarta, Hanoi, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Taipei, Tokyo, and Seoul. What is interesting is that, excluding Beijing, there is a clear regional pattern in which life satisfaction is highest in South Asia, lowest in Northeast Asia, with Southeast Asia located in the center.

Fig. 1: City average values for ideals and reality of meritocracy and life satisfaction. (Figure courtesy of the author, 2023).

In order to see how the gap between the ideal and reality of meritocracy is related to life satisfaction, the gap between the ideal and reality was calculated in terms of the difference and ratio between the two, and life satisfaction in each city was also calculated. The life satisfaction levels were traced, and as expected, a clear tendency for life satisfaction to decrease as the gap between the ideal and reality increased was observed. Life satisfaction was highest in New Delhi, where the gap between the ideal and reality was the lowest. Meanwhile, life satisfaction was lowest in Seoul, where the gap was the largest. Here, too, regional patterns are evident. Excluding Beijing, the gap becomes bigger and life satisfaction becomes lower in the following order: South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Northeast Asia.

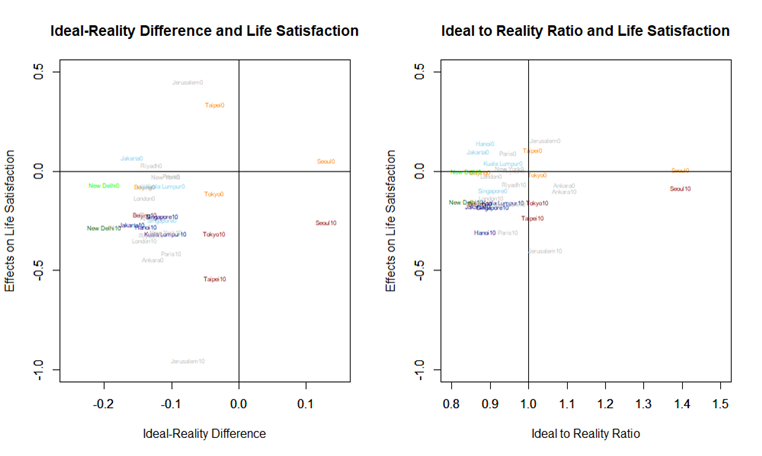

Individual-level multiple regression analysis was also conducted for each city. In this case, analysis was conducted based on the assumption that the impact of holding meritocratic ideals on life satisfaction would vary, depending on which social class an individual belonged to. Figure 2 shows the size of the impact of the gap between the ideal and reality on life satisfaction by city. The number zero associated with each city name represents the lowest social class, and ten represents the highest social class. If the city is located above the zero horizon, it means that the larger the gap between the ideal and reality, the higher the satisfaction with life. Conversely, if it is located below zero, it means that the larger the gap, the lower the satisfaction. A few things stand out. First of all, regardless of social class, most groups are distributed below the horizontal line. This means that, in general, the larger the gap, the lower one’s life satisfaction. Second, in most cities, it was found that the higher the social class, the more pronounced the negative effects of the gap. Thinking highly of the ideal of meritocracy, but facing a reality in which its practice is lacking, seems to have the effect of lowering life satisfaction among society’s upper classes. Third, this trend was particularly evident in Jerusalem and Taipei. Fourth, in Jerusalem, Taipei, Jakarta, and Seoul, it was found that the lower the social class, a greater gap between the ideal and reality of meritocracy corresponded with higher life satisfaction.

Fig. 2: Effects of the gap between the ideal and reality of meritocracy on life satisfaction (at the level of the individual). (Figure courtesy of the author, 2023).

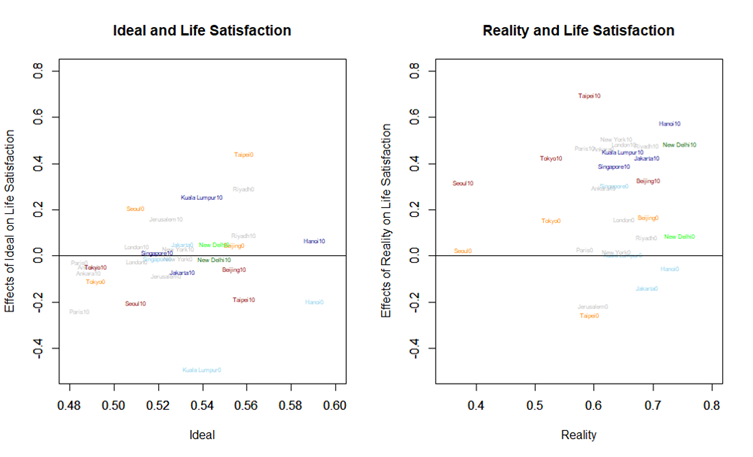

It was confirmed that when the ideal of meritocracy is high but reality does not follow, life satisfaction is low, especially for people belonging to a high social class. In order to examine the effects of social class in terms of ideal and reality, the two were examined separately by applying individual-level multiple regression analysis. The left side of Figure 3 shows the impact of the ideal of meritocracy and the right side the impact of meritocracy’s reality on life satisfaction. Similarly, the number zero refers to the lowest social class and ten refers to the highest social class. In terms of the ideal of meritocracy, the values generally cluster around the horizontal line, indicating that the ideal itself does not have a significant impact on life satisfaction. However, if one belongs to the lowest social class and has a high ideal of meritocracy – especially in places like Taipei, Riyadh, and Seoul – a tendency to have higher life satisfaction is partially observed. On the other hand, the values for the reality of meritocracy are mostly located above the horizontal line, indicating that they generally have a positive effect on life satisfaction. The impact of the reality of meritocracy was clearly positive in cities particularly when social class was almost always high. This is probably because people belonging to high social classes have high life satisfaction and tend to believe that meritocracy is well realized in their society.

Fig. 3: Effects of the ideal and reality of meritocracy, respectively, on life satisfaction (at the level of the individual). (Figure courtesy of the author, 2023).

Taipei showed the most interesting results in the individual-level analysis examined above. Here, the effects of the ideal and reality of meritocracy on life satisfaction had opposite effects depending on social class. When social class is the lowest, a high ideal has the effect of increasing life satisfaction, but this effect gradually decreases as social class increases. On the other hand, believing that meritocracy is implemented in reality was negative for life satisfaction when the social class was low, but gradually changed in a positive direction as one’s social class went up. This pattern was similarly observed in Seoul.

To conclude, belief in meritocracy, especially a situation in which there is a high ideal of meritocracy but reality does not follow, was found to have a negative relationship with life satisfaction. And this relationship was more pronounced for people of a high social class. When the ideal is too high or the reality was believed to be too low, people, especially those belonging to high social classes, showed low levels of life satisfaction. The best examples of this were the respondents from Taipei and Seoul. In these two cities, more than anywhere else, the higher the ideal, the lower the life satisfaction of people from higher social classes. Interestingly, these two cities, along with Tokyo, are the cities where the gap between the ideal and reality of meritocracy was found to be the widest and where people’s life satisfaction was found to be the lowest.

Yong Kyun Kim, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science & International Relations, Seoul National University, yongkyunkim@snu.ac.kr