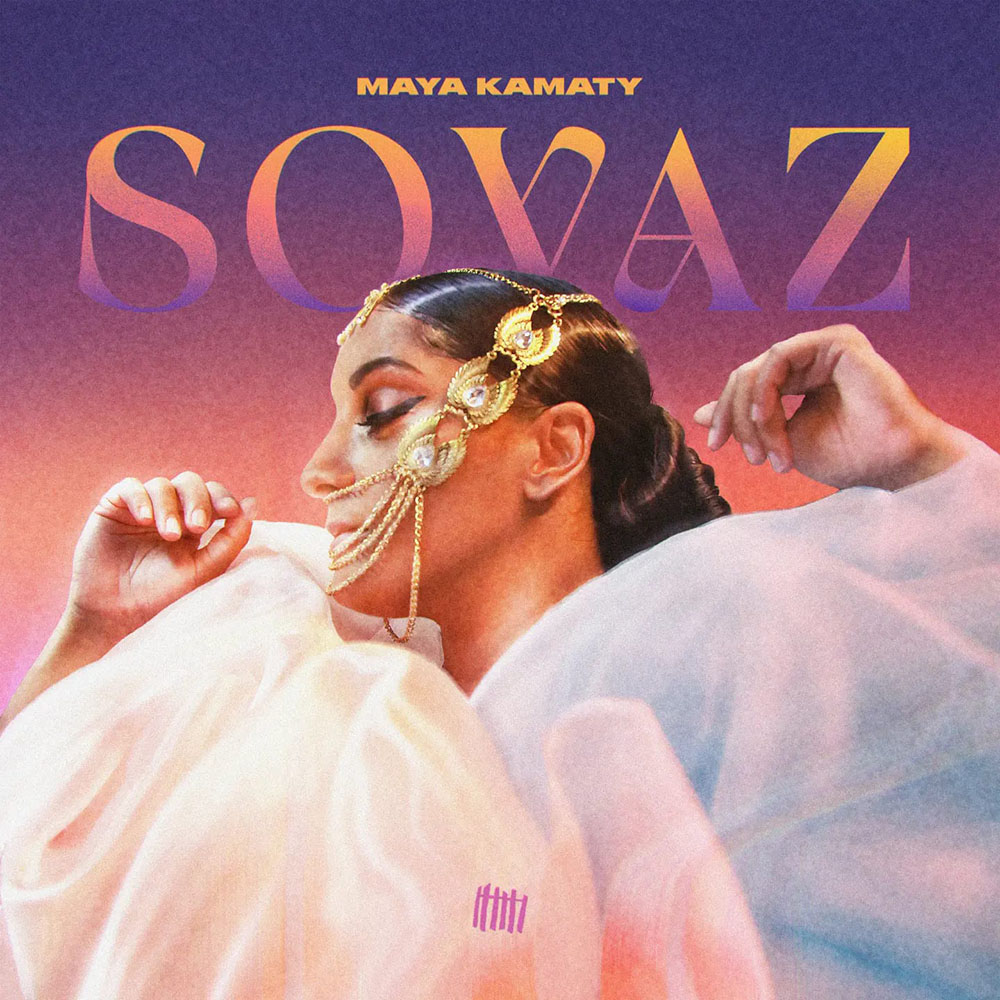

Maya Kamaty: Creole Musical Innovations

“Sovaz,” the title track of Maya Kamaty’s latest album, starts with a warning: the gloves are off [fig.1]. Her songs are now impudent, brazen. “Sovaz” is a Reunionese Creole term from Kamaty’s home island in the Mascarene archipelago of the Southwest Indian Ocean. To a French speaker ‘sovaz’ sounds like ‘sauvage,’ which can best be translated as ‘wild.’ In interviews, however, the songwriter and musician translates it as ‘insolente’ in French, while her translation of the lyrics in English online reads as “loud.” The French and Reunionese Creole homonyms signal a telling semantic shift when illuminated by Reunion Island’s history of slavery and French colonisation. It has been well-established that colonialist propaganda – and, prior to that, discourses surrounding the slave trade – portrayed non-Europeans as uncivilised people, savages who were either only good for hard labour, or to be educated by colonisers to become worthy citizens of a modern world. In becoming ‘insolent,’ ‘sovaz’ took on the more positive meaning of ‘rebellious.’ In other words, what makes someone ‘sovaz’ is their unwillingness to abide by prescribed rules and norms, which, in a colonial context, are the expression and extension of a racist state and oppressive economic power. Sovaz is defiance.

Fig. 1: Album cover, SOVAZ by Maya Kamaty. (Artwork by Arnaud Jourdan, produced by Lamayaz)

Kan Mon Bébet i lèv

When my blood boils up

I fé tranm loraz

Even storms cower

Rant dann ron

Gloves out, go

Pa kapon

No fear, no

Wi Mi lé Sovaz

Yes I’m proudly loud

Sovaz, however, is not only a reference to Reunion Island’s colonial past. The English translation into ‘loud’ indicates Kamaty’s disregard and denunciation of standards of femininity that demand women be both physically and socially pleasant and agreeable. A ‘loud’ woman is unappealing, threatening, vulgar. To quote Virginie Despente, she is not a prized item on “the universal market of the consumable chick.” 1 By claiming this epithet, Kamaty announces the political commitment of her music that is in step with the musical and visual aesthetic shift she took with her previous EP. Distinctively more trap and electro than her two previous albums, SOVAZ is both anchored in the local Reunionese context and stylistically accessible to global audiences, as it draws on recognised urban sounds and aesthetics from the hip hop scene, and iconic styles and body postures first popularised by African-American musicians. This article will introduce readers to Maya Kamaty’s production and career before discussing what her work can tell us about the adaptation and preservation of Indian Ocean Creole heritage and, by extension, the heritage of minority cultures in the current age of globalisation.

Reunion Island: Music and Politics

While performing, Kamaty exudes an extraordinary presence and energy. Her vocal dexterity, her tracks’ furious beats, and her melancholic melodies command the audience’s attention. Whether accompanied by a band or solo with her music production device, Kamaty will always at some point play the kayamb [fig. 2]. Traditionally made of cane flower stalks filled with seeds, the kayamb is one of the instruments used for playing maloya, a popular musical genre in Reunion Island. Recognised in 2009 as intangible world heritage by UNESCO, maloya was introduced on the island by African and Malagasy enslaved people, who played it during spiritual ceremonies. 2 In Reunion, it soon became a medium through which the enslaved lamented about and protested against their condition, asserting maloya as the music of the people and workers, who after abolition were joined in large numbers by indentured Indian labourers. Indeed, ‘Kamaty,’ Maya Pounia’s stage name and middle name, is of ‘Malbar’ (Malabar) origin and serves as a reminder of Indians’ influence on Reunionese music culture.

One of France’s so-called “old colonies,” Reunion Island became a French overseas department in 1946 and remains so to this day. Music in general and maloya in particular are sites where the conflicted relationship between Reunion and France has been articulated and negotiated, especially during the 1970s, a period marked by a renewed interest in Creole Reunionese culture. Against the assimilationist, paternalist, and colonialist deployment of Creole language and folklore by the elite, an artistic production emerged that used Reunionese culture to claim cultural and political autonomy from the metropole. 3 The political component of this struggle was led by the Parti Communiste Réunionnais (Reunionese Communist Party, abbreviated as PCR), who actively renewed maloya music. The genre “became the symbol of censured and oppressed poor lower-class culture,” and, because of its association with PCR activities, “was systematically disrupted and suppressed by the authorities.” 4

It is in this context that Kamaty’s parents, Gilbert Pounia and Anny Grondin became, respectively, the leader of Reunion’s most successful band (Ziskakan) and an author and storyteller. Pounia and Grondin were important figures of an artistic movement working against Reunionese people’s acculturation. They saw Reunion’s aesthetic and political alignment with France as not only precluding Reunionese culture from thriving, but also from being open to other influences, such as neighbouring Indian Ocean cultures. 5 In writing and singing in Reunionese Creole and adopting features from maloya, Kamaty continues the fight of her parents’ generation. At the same time, the challenges now lie elsewhere than solely in Reunion’s relationship to France. How can Reunionese artists, and other minority artists, carve out a space on the global music scene? With her music, Kamaty transcends geographical borders by reflecting on women’s condition, increasing political corruption, wealth inequalities, and the cult of the body propagated by social media [fig. 3].

Fig. 3: Cover of Maya Kamaty’s single “Alibi.” (Picture by Eric Lafargue, produced by Lamayaz)

The Indian Ocean Islands’ Music Industry

My research on Maya Kamaty’s music emerges from this question: what happens to Creole cultures and artistic productions in our era of globalisation? Defined by a greater international circulation of cultural goods aided by the rise of new technologies, contemporary globalisation leads to an increased internationalisation of the cultural scene, one that is no longer (only) a euphemism for United States imperialism. In the Indian Ocean, globalisation is also associated with the long history of oceanic trades that fostered cultural exchanges and transformations. However, the contemporary music industry, where Kamaty and her peers such as Sodaj and Labelle innovate musically, illuminates new cultural networks connecting Indian Ocean territories. 6 Such territories include small island nations such as Reunion, Mauritius, the Comoros, and the Seychelles, for which competing on the global market is often a challenge.

Unevenly developed and unequally decolonised, these islands share histories of contact, colonial legacy, and geography that underpin their contemporary cultural collaborations, as manifested in festivals, prizes, and professionalisation initiatives that raise the profile of local artists. For instance, Kamaty began her career performing at the Sakifo festival in 2013, when she competed for and was awarded the Alain Peters Prize that enabled her and her band to perform on the main stage of the festival the following year [fig. 4]. The award also included a one-week residence at the Kabardock studio in Reunion and financial support from Sacem, a music publishing association. Sakifo is one of the largest and longest running contemporary music festivals in the region. It is dedicated to including “local artists from the Indian Ocean and the rest of the world” to showcase “diverse aesthetics, representative of cultures, countercultures and current trends.” 7 The same year, Kamaty was also awarded the Music of the Indian Ocean award. Only musicians working in Madagascar, Seychelles, Comoros, Mayotte, Mauritius, Reunion, and Rodrigues, could compete for the prize. Winners received coaching sessions by music professionals and gained access to the international festival scene. While this prize is no longer running, Sakifo’s success led to the creation of the Indian Ocean Music Market (IOMMA), where selected artists from across the Indian Ocean – eastern and southern Africa, Australia, India, as well as all the islands in between – can showcase their work to international stakeholders in the music business. These regional events play an important role in establishing and sustaining Indian Ocean cultural networks and supporting the global circulation of its music. They are also important avenues for Indian Ocean scholarship and transcultural encounters. In this context, Reunion’s thriving music scene, its administrative status, and its history of creolisation make the island an attractive hub and a major player in the Indian Ocean music industry.

Fig. 4: Maya Kamaty at Sakifo festival in June 2021, Saint Pierre, Reunion Island. (Photo by Mikael Thuillier)

Music Videos: Creole Heritage on the Move

Another key element of contemporary musicians’ careers is their online presence. While social media posts are easy tools for promoting new releases and sharing news about tour dates, they also serve to circulate public images of the performer that connect them to a community of style and taste. 8 Online engagement gives artists the opportunity to be ‘read’ through recognisable aesthetic codes by a global audience. Circling back to Maya Kamaty’s latest album SOVAZ, I would like to discuss one of its distinctive features: each track has been released with an accompanying music video. Adjacent to the music, videos are above all a promotional tool, but their key economic function “is to promote not the individual song, but rather the artist or band who perform it.” 9 Online musician forums and blog posts describe the music video as a business card – in other words, the level of legitimation acquired will depend on the quality of the video, which works as a proof of the artist’s professionalism. Kamaty has released many original and polished music videos that showcase not only her talent but the expertise of other local artists, technicians, and dancers.

Fig. 5: Music video stills from ‘Sovaz’, director Formidable(s) Aloïs Fructus, produced by Lamayaz, dancers In Motion Crew.

In tune with her musical turn, Kamaty’s music videos borrow from the aesthetic codes of hip hop while also being anchored in and referring to Reunionese politics and heritage. The music video of “Sovaz” was shot in Reunion and includes different sets reminiscent of Creole history, especially of the creolisation of the Indian diaspora. The video moves between an auditorium where Kamaty both watches and appears in a movie that mixes references to Bollywood and Hollywood; a grocery store that can be read as a nod to the history of Gujarati merchants; and a sugar cane field where Kamaty drives an ox cart, an obvious reference to slavery and indentureship [fig. 5]. In this set, Kamaty is preceded by dancers adorned with flower garlands and dancing to the sound of the sitar. One last set shows an ironically regal looking Kamaty sitting on a white peacock chair [fig. 6]. On her right-hand side a small boar or a ‘cochon marron’ is wearing a garland, symbolising the defiance of the enslaved via the history of marronage. Indian coded, the garland matches the video’s Indian theme, but also signals the Afro-Asian foundations of Reunionese Creole heritage.

Fig. 6: Still from ”Sovaz” music video, director Formidable(s) Aloïs Fructus, produced by Lamayaz.

As the chorus of the song indicates – “Kri amwin Queen / Diva,” – Kamaty, here, is a queen. But, we may ask, a queen of what? She is the queen of Reunion Island’s musical future, cognisant of its complex and violent history and moved by the ongoing creolisation of an already creolised heritage. Kamaty’s music and aesthetic continue to redefine a ‘traditional’ genre, which according to UNESCO is “threatened by social changes and by the disappearance of its main exponents and the practice of venerating ancestors.” 10

Rosa Beunel-Fogarty is lecturer in English and postcolonial literature at City Saint George’s, University of London. She specialises in Indian Ocean Island literature and researches on the culture of creolised societies, archipelagic theory, and the relationship between local cultural production and global networks. E-mail: rosa.beunel-fogarty@city.ac.uk