May Fourth at 100 in Singapore and Hong Kong. Memorialization, localization, and negotiation

As 2019 marked the centenary of China’s May Fourth demonstrations, in this piece, we reflect on how this event and the broader movement surrounding it were commemorated in Singapore and Hong Kong, with reference to Southeast Asia. We probe the question of how the movement’s ‘memorialization’ and ‘localization’ in these two settings were shaped by both their connection with China and the history of British colonialism. Politicians, intellectuals, and students negotiated the meaning of the movement congruent with a variety of agendas, whereas the commemorations also coincided with another anniversary in Singapore and occurred amidst political protests in Hong Kong.

When the centenary of China’s 1919 May Fourth demonstrations drew near, China watchers turned their gaze towards the politics of remembrance in the People’s Republic of China. They noted the official emphasis on patriotism and the ‘spirit of youth’, thus leaving the May Fourth legacy of ‘Mr Science’ and ‘Mr Democracy’ all but buried. Official interpretations foregrounded what is now known as the May Fourth Incident, or the gathering of thousands of students at Tiananmen in Beijing in response to the transfer of Germany’s former rights in Shandong to Japan. Later, however, the term May Fourth also came to denote a range of cultural, political, social, and ideological advancements in the years before and after 1919. Seen through this lens, the movement spurred the reorganization of the Kuomintang, witnessed the rise of ‘-isms’ – individualism, nationalism, liberalism, and feminism among them – and facilitated the adoption of the vernacular. Furthermore, it instigated student and workers’ movements and the expansion of the public sphere. Since the movement contained all these facets, it is not surprising that there are as many ‘May Fourths’ as there have been commemorations of May Fourth.

Protest against extradition bill in Hong Kong, June 2019.

While the shifting meaning of May Fourth in the People’s Republic of China has been gaining attention, a less frequently asked question is: What did and does the movement mean for Chinese communities outside of mainland China? To answer this, we first need to revisit developments in scholarship. In an article written for May Fourth’s centenary, the historian Edward Wang pinpoints three main trends in Chinese scholarship on May Fourth since the 1990s. He terms these trends ‘individualization’, ‘localization’, and ‘memorialization’. The first trend, individualization, refers to research on renowned intellectuals associated with the movement, such as Chen Duxiu (1879-1942) or Lu Xun (1881-1936). Remarkably, their ranks now include previously denounced liberal intellectuals such as Hu Shih (1891-1962), or critics of the movement, such as those around the journal Critical Review [學衡], including Wu Mi (1894-1978), Mei Guangdi (1890-1945), and Hu Xiansu (1894-1968). Renewed interest in the latter also relates to the so-called ‘Republican fever’ and scholarly trends such as ‘national studies’, as well as to the reassessment of ‘conservative’ critics of May Fourth as moderns and cosmopolitans.

Secondly, localization denotes a change from the study of May Fourth in Beijing to cities and regions across China, but also to transnational connections with movements such as the March First Movement in Korea. A well-known study in this regard is Erez Manela’s The Wilsonian Moment (2007), which links May Fourth with other national self-determination movements through the Paris Peace Conference. May Fourth has hence also become subjected to the so-called ‘transnational turn’ in academia. Finally, memorialization, or how May Fourth has been remembered, reveals the influence of the international turn to history and memory since Pierre Nora famously popularized the notion of lieux de mémoire [sites of memory]. In recent publications on May Fourth, scholars interrogate existing ways of remembering the movement.1

Singapore and Hong Kong: local identities and connections

To explore how the localization and memorialization of May Fourth intersect in the May Fourth centenaries in Singapore and Hong Kong, the authors of this piece, together with Huang Jianli, held a panel discussion at the National Library in Singapore in November 2019.2 To some extent, we have all studied May Fourth from the angles that Edward Wang describes. Els van Dongen has investigated the re-evaluation of May Fourth ‘conservatives’ in mainland China and transnational interactions involving debates on ‘radicalism’ and the meaning of May Fourth after 1989. David Kenley was an early exponent of the transnational perspective on May Fourth and analyzed its meaning in Singapore in his well-known monograph New Culture in a New World (2003). Finally, Huang Jianli has written extensively on questions of commemoration, historiography, and student activism in both China and Singapore.3

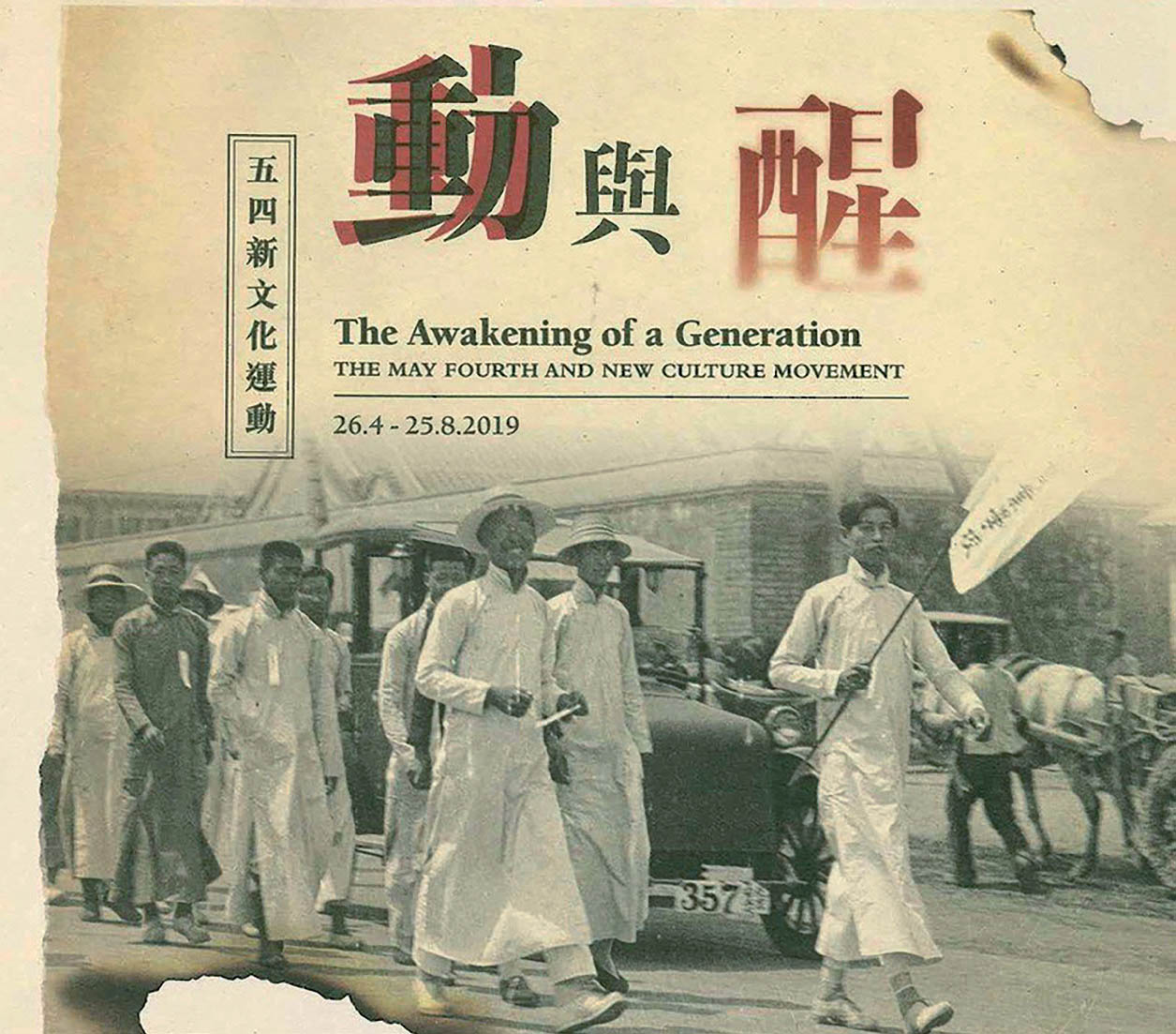

Leaflet for exhibition 'The Awakening of a Generation: The May Fourth and New Culture Movement' at Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum, Hong Kong.

Why Singapore and Hong Kong? One reason is that both witness a complex dynamic in terms of how they relate to mainland China. In his book, Kenley asked: What did a movement with nationalist traits come to signify among members of the Chinese diaspora? He has answered this by situating the movement between the oft designated twin themes of the movement, namely ‘nationalism’ and ‘enlightenment’, and that of ‘transnationalism’. However, both cities also manifest a strong sense of local identity shaped by both interactions with China and the history of British rule. Indeed, in May Fourth in Hong Kong [五四在香港] Chan Hok Yin has analyzed interpretations of May Fourth based on three historical perspectives: that of British colonialism, that of nationalism before British rule, and that of local identity.4 In spite of the vastly different trajectories of both cities, local identity has been shaped and discussed through and in response to this double connection of the changing relation with mainland China and the long shadow of British rule. What’s more, in both places ideological divisions have intersected with linguistic divisions, including but not limited to an English-educated versus a Chinese-educated elite.

Returning to the May Fourth period, what forms did the movement take in Singapore and Hong Kong? Although it is equally hard to define May Fourth outside China, large-scale protests also occurred in these places in the spring of 1919. Throughout May, Chinese residents of Singapore called for boycotts and strikes, and these calls amounted to violence on the night of 19 June 1919. The Straits Times reported that a mob “made bonfires in the middle of the roads, and with the air filled with piercing screams and shouts, scenes of wild confusion reigned”.5 Eventually the Governor called on the sailors of the docked warship Manchester to help patrol the city. By the early morning, the demonstration died out, but it had caused severe damage, had claimed four lives (two Chinese and two Indians), had seriously injured eight individuals, and had led to the arrest of over 130 participants. Similarly, in Hong Kong, students and journalists led rallies and demonstrations while business leaders called for a boycott of Japanese-made products. Nine students were arrested and fined. Their crime? They marched in the street holding umbrellas with 國貨 [national products] written on top.

Nevertheless, as was the case in China, these 1919 protests in Singapore and Hong Kong can best be understood as part of a larger, multi-year movement that transcends temporary nationalist concerns. Community leaders were also motivated by a commitment to greater democracy, and by a desire to implement new intellectual trends and ideas. They sought to destroy the icons of the past and usher in a new era of science and enlightenment. But May Fourth in Singapore and Hong Kong had some rather distinct elements as well. Intellectuals in Singapore used the movement to call for more local control over Singapore affairs. In some ways, the movement was an internal power struggle over the issue of what it meant to be Chinese in Singapore. Essayists, poets, and commentators repudiated some of the literary trends emerging in China, calling instead for greater attention to local themes. Often, the struggles pitted the more recently arrived immigrants against the more long settled Chinese residents within Singapore.

Negotiating the meanings of May Fourth in 2019

While this brief detour to the May Fourth period already reflects the tensions between the connection to events in China and the quest for local distinction, commemorations of May Fourth since 1989 also reveal the impact of the legacy of colonialism and the Cold War. With reform and opening up in China, renewed interactions occurred between scholars in mainland China and those in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, Europe, and the United States. Under the dominant narrative of economic reform, and with debates on the East Asian economic miracle, May Fourth became negatively associated with ‘radicalism’ and ‘revolution’, both among Chinese communities worldwide and among mainland scholars.

In a 2009 article published in Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao [联合早报], leading intellectuals Wang Gungwu and Zheng Yongnian already criticized the ‘ideologization’ of May Fourth and argued instead for an open attitude of discussion. They called for a move beyond the simplistic praise of the ‘May Fourth spirit’ in revolutionary times and the drastic denouncement of May Fourth as radical in peaceful times. Whether this objective was achieved in 2019 was, however, another matter.6 In Singapore, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, George Yeo, used social media to pen an essay on the May Fourth centennial. He wrote in glowing terms about its legacy and the tremendous accomplishments of the Chinese people in the century since. The ‘dramatic change’, according to Yeo, was that China, from being spat upon a century ago had now become ‘increasingly feared’ by major powers. But he also used the opportunity to issue some warnings and veiled criticisms from the vantage point of the globalized and multi-ethnic city-state. He said: “It will be a mistake if the centennial message of May Fourth is a continued emphasis on standing up to foreigners”. Instead, he called for a revised New Culture Movement that would be beneficial to all mankind, embracing multiculturalism and religious diversity.7

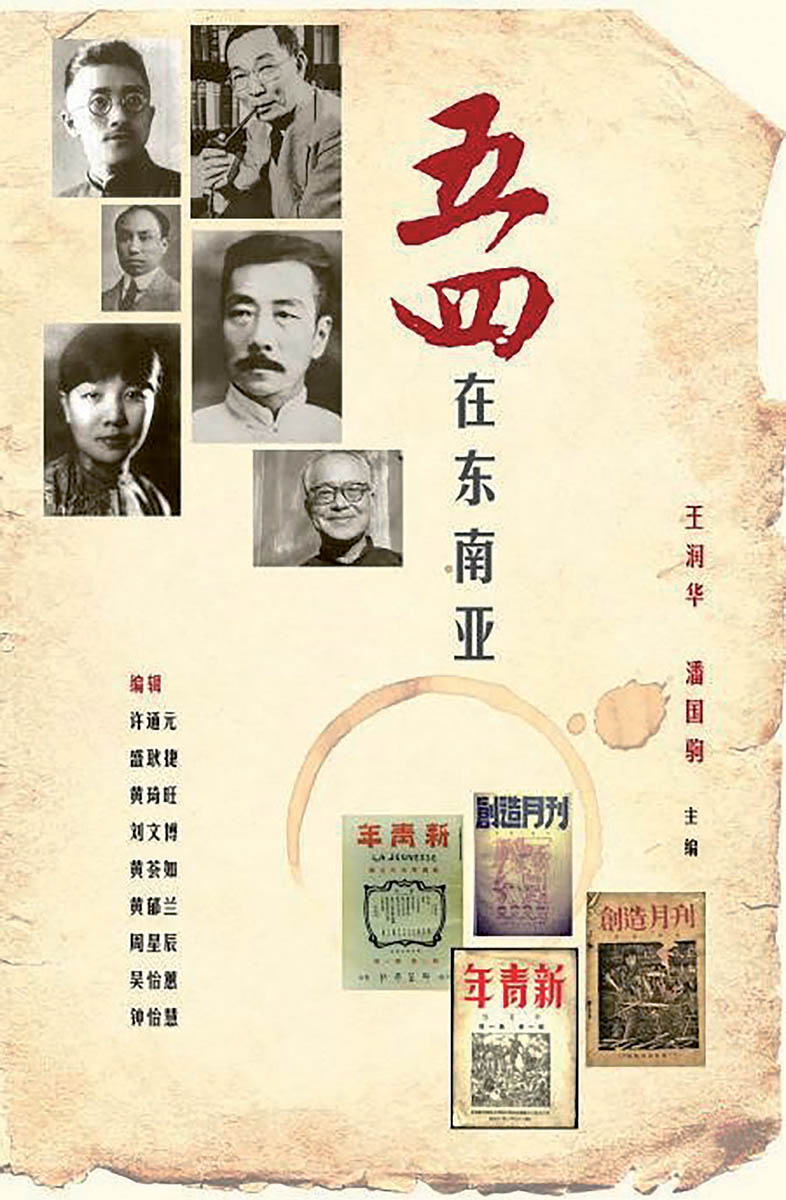

Book cover of May Fourth in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Bafang wenhua chuangzuoshi, 2019).

Besides politicians, Singapore’s intellectuals and associations also took part in the commemoration of the May Fourth centennial. For example, on 4 May 2019, the Nanyang Confucian Association held a symposium in the historic Chinatown entitled ‘From Opposing Tradition to Returning to Tradition’, which featured speakers from Taiwan and mainland China. At the event, reference was also made to a Facebook post by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in which the latter wrote: “A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots”. Also, several historians, sociologists, political scientists, and literature studies scholars contributed to the 2019 publication May Fourth in Southeast Asia [五四在东南亚]. The editors of the volume considered May Fourth to have ushered in an age of democracy, knowledge, and science, calling it “a precious cultural heritage for all mankind”. But contributors also noted how the Chinese in Southeast Asia had reinterpreted May Fourth for their own benefit. For example, Guo Huifen discussed the emergence of a unique form of writing, namely New Malayan-Chinese Literature. Referring to Fang Xiu, she ascribed the emergence of this literature to the ‘internal’ demands of local Chinese and the ‘external’ influence of May Fourth’s Literary Revolution.8 Other contributors to the volume discussed May Fourth in relation to themes such as education, newspapers and periodicals, Sinophone literature, translations of May Fourth writings, or anti-colonial sentiment across Southeast Asia.

In other words, local intellectuals utilized May Fourth to create an intellectual space between them and their counterparts in China. This ‘localization’ of May Fourth in Singapore had also been present in previous commemorations according to Huang Xianqiang and Shi Yan, who studied May Fourth remembrance in Singapore through newspaper articles and Chinese associations. Similarly, writing about May Fourth in Hong Kong, Chan Hok Yin has argued that the May Fourth legacy has been subjected to reinterpretations by various actors to achieve shifting goals at critical moments in Hong Kong’s history. Calling for patriotism, progress, reform, or democracy, they defended their respective political positions with the help of May Fourth vocabulary.9 Even a century after the events, negotiating the meanings of May Fourth is by no means complete.

Commemorations and coincidences

Both Singapore and Hong Kong also witnessed unintended, coincidental activities that seem strikingly reminiscent of the May Fourth Movement of a century ago. In Singapore, 2019 also happened to be the 200-year anniversary of the ‘founding’ of Singapore by the British Stamford Raffles. In January of last year, Singaporeans woke up to find the statue of Raffles—perhaps the most visible icon of Singapore’s colonial past—literally erased from public view with the help of creative artists employing optical illusions. A few days later, Raffles was visually restored to his former perch but found himself joined by four new statues of Sang Nila Utama, Tan Tock Seng, Munshi Abdullah, and Naraina Pillai. These four, representing the main ethnic groups of Singapore, challenge the traditional colonial narrative privileging the role of the British. While the vanishing Raffles statue was not directly tied to the centennial May Fourth commemorations, the iconoclastic link between the two is striking. Interestingly, one Straits Times letter writer quickly pointed out that Raffles was joined only by other men and asked, “where are the women?”10

The statue of Stamford Raffles surrounded by four new statues of Sang Nila Utama, Tan Tock Seng, Munshi Abdullah, and Naraina Pillai.

Likewise, Hong Kong also had official and unofficial commemorations coinciding with the May Fourth centennial. For example, the Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum in Central, Hong Kong hosted a multi-month exhibition titled ‘The Awakening of a Generation: The May Fourth and New Culture Movement’. The exhibition contained copies of New Youth [新青年] and other journals from 1919, as well as a collection of photographs and biographies of the movement’s leaders, and discussions of the participants’ goals. Most of the items were on loan from the Beijing Lu Xun Museum and the exhibition largely held to the Communist Party’s official interpretation of May Fourth as having developed into a “nationwide patriotic movement supported by all walks of society” distinct from the iconoclastic intellectual, cultural, and political trends of the era.11

There were, however, some newer artefacts displayed in the exhibition. Students from the Academy of Visual Arts of Hong Kong Baptist University created original artwork interpreting the meaning of the movement in the form of sculpture, calligraphy, seal engraving, and collage. One of the images showed the character 民 (meaning ‘people’ or even ‘democracy’) dripping blood and transforming into a question mark. In the caption, the artist asked: “As time goes by, what will democracy become? What will people think of it? Will it make society fairer and better? Or will it become a means of exploitation?” Another student wrote in calligraphy, ‘Nation, Power, Traitor’. The accompanying caption read, “Inspired by the slogan of the May Fourth Movement ‘Fight for sovereignty externally, get rid of the traitors at home’. Power and traitor are always in a close relationship, even now”. Still another student created a collage of the May Fourth intellectual Hu Shih. The artist explained, “The work originates from Hu Shih’s article entitled ‘Our Hopes for the Students’. It stresses that those in power should not suppress the student movement, and reminds the students not to be snared by politicians”.

Umbrellas played a role in the 1919 Hong Kong student boycotts and protests. Not surprisingly, the student artists also co-opted the umbrella in their contemporary art works. In one seal engraving, the artist depicted a police officer chasing after a group of umbrella-wielding students. In another piece, the artist repurposed umbrella handles to create seal engravings. The caption read: “This set of seals invites visitors to reimagine and develop their understanding of how the movement has shaped contemporary times”. While the symbol of the umbrella is more often associated with 21st century Hong Kong protests, these works of art clearly demonstrate the use of the May Fourth past to empower the activists of today.

While the Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum staff planned and created the May Fourth commemoration before the protests erupted in the streets of Hong Kong, it is impossible not to reflect on those protests in light of the May Fourth centennial. On 9 June 2019, approximately 1,000,000 demonstrators took to the streets in Hong Kong. Much like their compatriots of 1919, they were angry at their government and demanded greater accountability and democracy. Specifically, they asked for the withdrawal of the controversial extradition bill that they claimed was eroding Hong Kong’s civil liberties. But beyond this, the protests were also about asserting independence and distinctiveness relative to the mainland. We cannot ignore the significance of student leadership in both cases, with students wielding their umbrellas as a sign of resistance.

One hundred years after the events in Beijing, it is clear that scholars, politicians, and activists are still contesting the legacy of the May Fourth Movement, both in China and across Chinese communities. As seen in Hong Kong and Singapore, the designated May Fourth themes of ‘nationalism’ and ‘enlightenment’ could take on transnational forms in support of China, but they could also be transformed for the advocacy of distinct local identities and contemporary concerns.

Els van Dongen, Assistant Professor of History, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore evandongen@ntu.edu.sg

David Kenley, Dean of Arts and Sciences, Dakota State University, USA david.kenley@dsu.edu