Malay and Islam-Centric national narratives: modern art in Malaysia during the 1980s

The 1971 National Culture Congress could be seen as the first official attempt to shape arts and culture in Malaysia. Inspired by increasingly pro-Malay government policies, Malay intellectuals convened at the University of Malaya in August that year to formulate the country’s policy on national culture. Three principles were established, namely, ‘Malaysian National Culture must be based on the indigenous culture of the people from the region’; ‘Elements from other cultures that are deemed proper and appropriate can be integrated as parts of the National Culture’; and ‘Islam as an important element in forming the national culture’.

Perhaps more influential than the National Culture Congress in arts and culture was a rise in Islamic consciousness and policies from the mid-1970s onwards in Malaysia. This Islamic consciousness emerged from the dakwah movement that could be seen in parallel with the rise of ABIM (Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia) and the 1979 Iranian Revolution. It can be argued that Islamic consciousness had important implications on the art practices among Malay artists during the 1970s and 1980s.

In general, scholars note that Islamic considerations first emerged conspicuously in modern Malaysian art in the 1980s. It is during this time that more art exhibitions, seminars and scholarly writings began to engage with Islam, through discussions of Islamic art and culture. So much so that many Malay-Muslim artists sought to marry Islamic concepts, in whatever guise, with a modernist attitude in art.

Modernist artworks based on Islamic aesthetics include those of Sulaiman Esa, Zakaria Awang, Ahmad Khalid Yusof, and Ponirin Amin, among others. These artists can be argued to have positioned themselves in a larger context of Islamic ummah [society] by applying Islamic design conventions, such as the Arabic Script or Jawi script, calligraphic motives and the Arabesque, the displays of verses from the Quran or the Hadith and epithets praising God’s supremacy, to their art and even shunning the depiction of human and animal figures in their work.

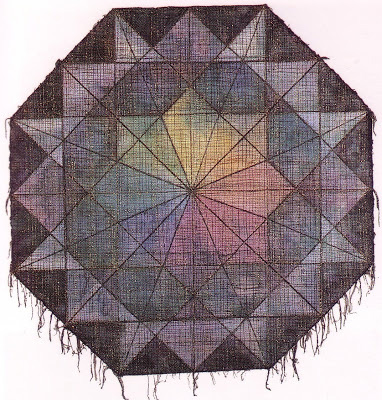

As modern artists, they were not restricted to traditional media, but adopted Islamic aesthetics or philosophy in their art-making. Sulaiman Esa’s Nurani series (Fig. 1), for example, is a quest for Islamic aesthetics through artistic contemplation of traditional Islamic arabesque design. Through the arabesque, Islamic spiritualism in the work is closely wedded to the experience of harmony and archetypical reality through the reflection of the One (Allah the Almighty) and the concept of unity of tawhid.

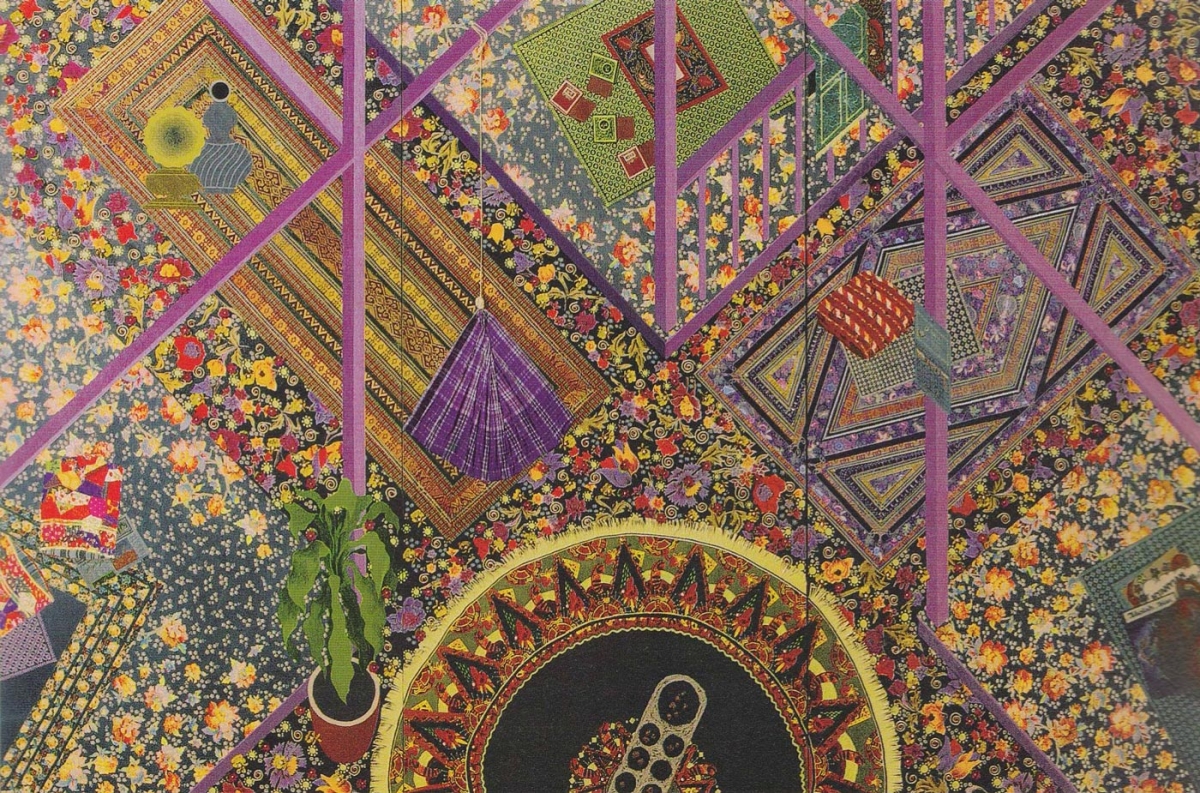

For the most part, Islamic art in Malaysia thrived because the artists who shunned figurative art did not do so out of Islamic interdiction, but because they empathized with the abstraction of the avant-garde. Indeed according to art critic TK Sabapathy, “Art reflecting the global Islamic revivalism in the 1980s has either aligned itself with tendencies in Abstract Expressionism or found kinship with decorative art.” (Figs. 2 and 3)

It is also important to note that the Islamisation of modern art in Malaysia was not down to solely the artist. Curatorial decisions played a key role too. The selection of artists and artworks for galleries and exhibitions often adhered to popular expectations of modern Islamic art. As a result such exhibitions and art were easily read as ‘Islamic’. It must be noted that the proclamations of the New Economic Policy (NEP), culture policy, and the Islamisation policies were part of the country’s nationalist phase, which inevitably reframed art with a nationalistic agenda. This collection of policies reinforced the state-endorsed national identity based on the hegemony of Malay culture despite the country’s multiracial complexion.

To conclude, external social and economic factors also shaped Malaysian art during the late 1970s and 1980s. For example, the economic gain attained by the Malays through the NEP resulted in the emergence of a new Malay middleclass as well. According to Joel S. Kahn, the NEP and the emergence of the new Malay middleclass further bolstered the construction of Malaysian identity through the reiteration of Malay culture in particular. With the resurgence of Islam at that time, it was not surprising that some artists carried their interest in Islam into art to expound some form of national identity.

Sarena Abdullah is a Senior Lecturer at the School of the Arts, and a Fellow Researcher at Centre for Policy Research and International Studies (CENPRIS), Universiti Sains Malaysia (sarena.abdullah@usm.my).