Malacca Sultanate as a Thalassocratic Confederation (1400-1511): Power Structure of the Pacified States

The Sultanate of Malacca is one of the many historic thalassocratic states which thrived from the inter-regional trade in maritime Southeast Asia. Though often viewed as a unified kingdom, it was in fact a loose confederation of various coastal and riverine polities, with its economic and political center situated at the port of Malacca. The main port was strategically positioned as the narrowest chokepoint of the Strait of Malacca, enabling the rulers to exert full control over the sea traffic and even to coerce the trading vessels to harbour at their port-city. The emergence and continuity of Malacca as a thalassocratic state always revolved around enhancing its ability to funnel as much wealth as possible to its main port, generated mostly from local and inter-regional trade. The political expansion of Malacca was to maintain strategic control over coastal settlements so that wealth could be generated at the main port through commodity exchange. Conquest for Malacca would not necessarily mean direct expansion of territory, but rather the acquisition of strategic control over coastal outposts, rival ports, and centers of production in order to reap as much profit as possible from the seaborne trade.

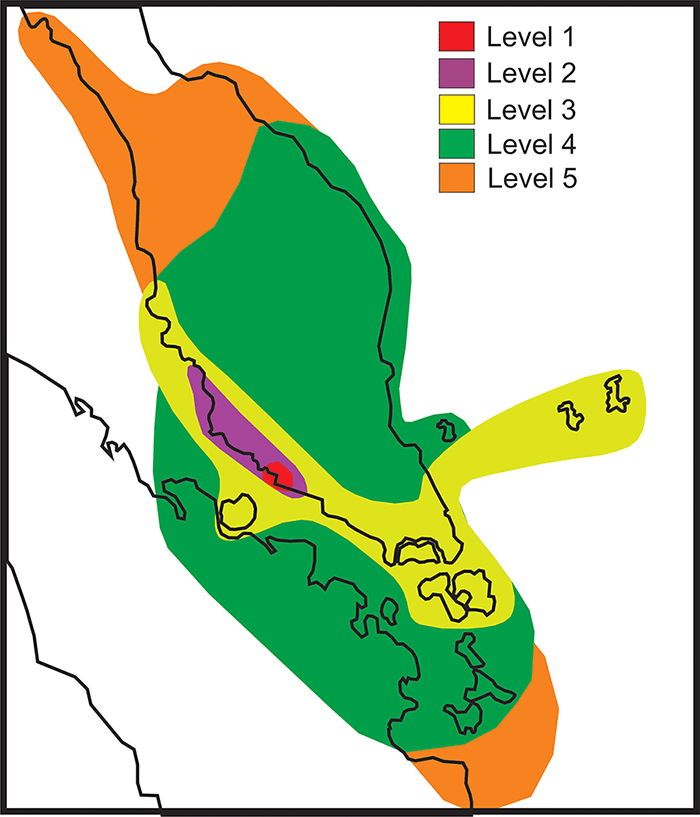

Information regarding the territorial expansion and administration of Melaka can be found in the Portuguese and Malay accounts: the Suma Oriental (written in 1512), Book of Duarte Barbossa (written in 1516) and the Salalatus Salalatin (compiled in the mid-16th century). All these materials provide important narratives as well as first-hand accounts of how the Sultanate of Malacca evolved and expanded from its founding by Parameswara until its demise under Sultan Mahmud Shah. These materials also give important information about how Malacca administered and exploited its subjugated territories. During the peak of Malacca’s power in the early 16th century, the sultanate covered most of the Malay Peninsula, Riau-Lingga islands, and south-eastern Sumatera. However, careful study of these historical accounts shows that the power structure of the sultanate was far from centralized or symmetrical. In Malacca’s capital, the rulers were supported by merchant-aristocrats and urban ruling elites. Malacca’s political framework was derived from its form of economy, which focused on controlling and capitalizing on the movement of people and goods by establishing and maintaining a network of subordinate groups with different degrees of loyalties. From these historical accounts, it is suggested that within the large area under the political influence of Malacca, there were five levels of political control [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1: Levels of political control within the Malaccan Sultanate (Figure by the author, 2022).

The first level – marked in red in Figure 1 – covers the area of Malacca’s center of population, possibly at the narrow strip of land between the Kesang river to the Malim river. It was ruled directly by the Sultan through his high officials known as the Bendahara, Temenggung, Laksamana, and Penghulu Bendahari. This area often consisted of the capital city as well as the main ports and settlements. The second level, marked in purple, was ruled indirectly by the royal court through the local chieftains appointed directly by the Sultan. They were known as Penghulu or Mandulika, who probably administrated the area according to Malaccan laws. The territories included Linggi, Klang, Jugra, Selangor, and Perak. These areas were also known to be rich in tin. The Sultan-appointed officials had to exercise tight control over these territories to maintain Malacca’s monopoly over the export of such resource. The third level, marked in yellow, comprised semi-autonomous territories granted by the Sultan to the Malaccan hereditary nobles to be ruled in his name. The areas included Muar, Batu Pahat, Beruas, Manjung, Rupat, Singapura, Siantan, and Bentan. These were coastal and riverine settlements located at the strategic chokepoints of the Strait of Malacca. Being administered semi-autonomously by the high officials loyal to the Sultan enabled the territories to serve as important outposts to control the sea traffic, for the defensive and economic interests of Malacca.

The fourth level, marked in green, was composed of autonomous kingdoms ruled by local rulers who were subordinate to Malacca. They included Rokan, Siak, Kampar, Inderagiri, Pahang, Kelantan, and Lingga, which were mostly potential rival ports pacified by Malacca. They were free to conduct local affairs, except in passing a death sentence, which required the Sultan’s approval. They also needed to send regular tributes and army personnel when requested. The pacification of these ports was meant to keep them under control, so that they would not rise up and threaten the commercial and military interests of Malacca. These ports often consisted of resource-rich coastal polities strategically positioned along the trade route, but with less political strength than Malacca. The fifth level, marked in orange, consisted of independent kingdoms with nominal allegiances to Malacca. Malacca had no effective political control over them, possibly owing to the distance and their political leverage, especially in terms of their military strength and ties with other regional powers. They probably had strategic partnerships in trade with Malacca, especially in the export of certain commodities such as rice and gold. They included Kedah, Pattani, and Jambi, which are all located at the northern and southern ends of the Straits of Malacca. Finally, there were maritime polities, which were not part of the Malacca political confederation, and often became its rivals, such as Aru and Pasai.

As a maritime confederation, Malacca’s consolidation of power had less to do with direct political dominance over territories or settled populations than with the control over the movement and distribution of goods and commodities in favor of its main port. As a result, the form of Malacca’s political control over its territories varied widely and was extremely asymmetric in nature. The different areas within the empire were administered with varying levels of political control, from direct rule by the court to a nominal recognition of suzerainty by local rulers. Due to economic necessity and demographic factors, such a system evolved organically to form a confederation that was structured by a fluid and adaptable network of relations between the dominant political center and its subordinate settlements. This was due to the fact that different areas would offer Malacca distinct strategic and economic advantages. Thus, in order to effectively capitalize on all of them in the interests of Malacca, there must have been particular forms of political arrangements for specific subordinate groups, depending on their economic strength, geostrategic location, and political leverage. Such was the true nature of Malay maritime statecraft, a complex and dynamic organization of political and economic bonds established between local chieftains, merchant-aristocrats, and the dynastic rulers.

Nasha Rodziadi Khaw is a senior lecturer in the Centre for Global Archaeological Research, Universiti Sains Malaysia. He received his Master's Degree (Archaeology) from Universiti Sains Malaysia and PhD (Archaeology) from University of Peshawar. He specializes in Historical Archaeology and Epigraphy-Palaeography. His research interests cover the history and archaeology of early Malay kingdoms as well as the epigraphy of the Malay Archipelago. E-mail: rnasha@usm.my