Lording over the Centre of Asia: Manuscript Arts of the Abu’l-Khayrid (Uzbek) Khans

In the 16th century, all the eastern Islamic empires were admixtures of Turkish, Persian, Mongol, Muslim, Iranian, and Central Asian elements. Specifically, they perpetuated Persian and Turkic literary and linguistic traditions, Islamic cultural and religious forms, and Mongol customs. The amounts of each of these ingredients led to dynastic differentiation that became markedly pronounced in the second half of the 16th century.

The main dynasties of this region and time period were the Timurids (ended in 1506), Mughals (started in 1526), Safavids (started in 1500) and Ottomans (ruling across the century and extending either end), and Abu’l-Khayrids (commonly called Shaybanid Uzbeks, ruling 1500–1598). Although the final dynasty’s administration was short-lived, the Abu’l-Khayrids had forced the Timurids out of Transoxiana (Central Asia) and made these princes begrudgingly relocate in India where they became the Mughals. Based in Bukhara and Samarqand, located in modern-day Uzbekistan, the Abu’l-Khayrids at their height took control of territories from the western borders of China to the Caspian Sea, wresting eastern Iran and northern Afghanistan from the Iranian Safavids. Expansive Abu’l-Khayrid reforms in political centralisation and fiscal policies within Transoxiana predated those in Iran. As the rivals to the late Timurids, early Mughals and Safavids, and Ottomans, the Abu’l-Khayrids presided over a strategic region. All of these other dynasties’ illustrated manuscripts and histories have been explored in detail, but in the case of the Abu’l-Khayrids, not even their courtly dynastic arts have been fully analysed, much less the commercial productions and those in ambiguous styles.

Illustrated manuscripts of the Abu’l-Khayrids are vehicles for many means of analysis. These can be grounded in the original era of Abu’l-Khayrid manuscript manufacture in the early-modern period, as well as in current geo-political contexts. The ramifications of better understanding topics and objects from the early-modern era radiate outward to illuminate the social, cultural, and political underpinnings of our modern age. Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts provide insight into deeper issues of sectarian coexistence and conflict, voluntary and forced migrations of artisans, and ethno-linguistic nationalities that continue to be negotiated in Muslim-majority countries. Designations of Persian and Turkish-speaking groups, and declarations of Sunni and Shi’ite adherence in faith, have delineated and dominated identities beginning in the 16th century. Moreover, recently-formed nations have harnessed Abu’l-Khayrid artistic heritage for political legitimacy and national aims, which underscores the importance of teasing out the cross-cultural and transregional factors shaping the original traditions.

Who are the Abu’l-Khayrids?

The dynasty I am designating by the name Abu’l-Khayrid has more often been labeled “Uzbek,” “Bukharan,” and “Shaybanid/Shibanid.” Following the Mongol conquests launched by Chinggis Khan, the peoples who would come to be the Abu’l-Khayrids hailed from present-day Kazakhstan. Groups referred to in period sources as Qazaqs and Uzbeks had common Mongol origins but by the second half of the 15th century, they were on their way to forming different political factions. The term “Uzbek” as it applies to the 15th and 16th centuries names a tribal confederation descended from Jochi (d. 1227), the eldest son of Chinggis Khan. Following the death of the Great Khan, a line traced through Jochi’s son Shaybani (who was active in the 13th century) ruled the Golden Horde in the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. Separate strains of these Shaybanids held power in Siberia, Khwarazm, and Transoxiana by the late 15th century. The Abu’l-Khayrid branch of the Shaybanids ruled initially from Samarqand, and later in the century from Bukhara. This group took root under Abu al-Khayr Khan who united various nomads of the Qipchaq steppe under the name “Uzbek” in the mid-15th century. Upon Abu al-Khayr Khan's death in 1467, his grandson Muhammad Shaybani Khan [Fig. 1] took over control and surpassed his grandfather's territorial gains.

Fig. 1: Portrait of Muhammad Khan Shaybani (d. 1510). Attributed to Bihzad. Circa 1507-1510, Herat or Samarqand. Cora Timken Burnett Collection of Persian Miniatures and Other Persian Art Objects, Bequest of Cora Timken Burnett, 1956. Metropolitan Museum of Art no. 57.51.29.

The appellation “Shaybanid” has frequented scholarly literature to refer to these 16th-century Abu’l-Khayrid Uzbeks in Transoxiana, but this is in fact erroneous. “Shaybanid” technically applies to all of the Jochid ancestors specifically descended from Shaybani, the grandson of Chinggis Khan, and not this later Muhammad Shaybani Khan who was born 300 years later. It is for this reason that I use the more accurate term “Abu’l-Khayrid” to refer to the 16th-century administration that reconstituted and resurrected Chinggisid rule in Central Asia. This was initiated under Abu al-Khayr Khan, and the consolidation of power and launch of a new dynasty was successfully carried out by his grandson Muhammad Shaybani Khan.

As a dynasty, the Abu’l-Khayrids occupy a curious position in scholarship, trapped between ethnic and linguistic labels. They are at times considered “too Turkish” to be categorised alongside other dynasties with Persian-speaking administrators. The arts of the dynasty have more often been considered “too Persian” to be grouped with art forms from dynasties associated with Turkic-speaking regions. A majority of their illustrated manuscripts are rooted in literary traditions of Persianate book arts; whereas Turkish literary works mostly appealed to the Ottomans, the Abu’l-Khayrids preferred works of Persian poetry, more akin to the Safavids in Iran.

Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts in the 16th century

What constitutes an illustrated Abu’l-Khayrid manuscript? Many of these intact specimens and now-dispersed folios are not the result of unified workshop practices, and the staff of a previous dynasty frequently stayed on in a conquered region to carry out the projects of new overlords. Better understanding these elusive objects expands our knowledge of materials and eras, revealing transregional and cross-dynastic exchanges. There is ease affixing a provenance to a codex when illustrative programmes are uniform and styles distinctive and attributable to one courtly workshop, such as that in Abu’l-Khayrid Bukhara. Classifying intact manuscripts as products of one dynasty or one time period is more difficult when the productions are not of royal patronage. Thus, the ugly ones make life very difficult for the scholar, and I am particularly attracted to less-elaborately illustrated texts produced by artisans operating within the Abu’l-Khayrid domain who migrated across courts and commercial hubs during periods of dynastic rivalry and economic strain.

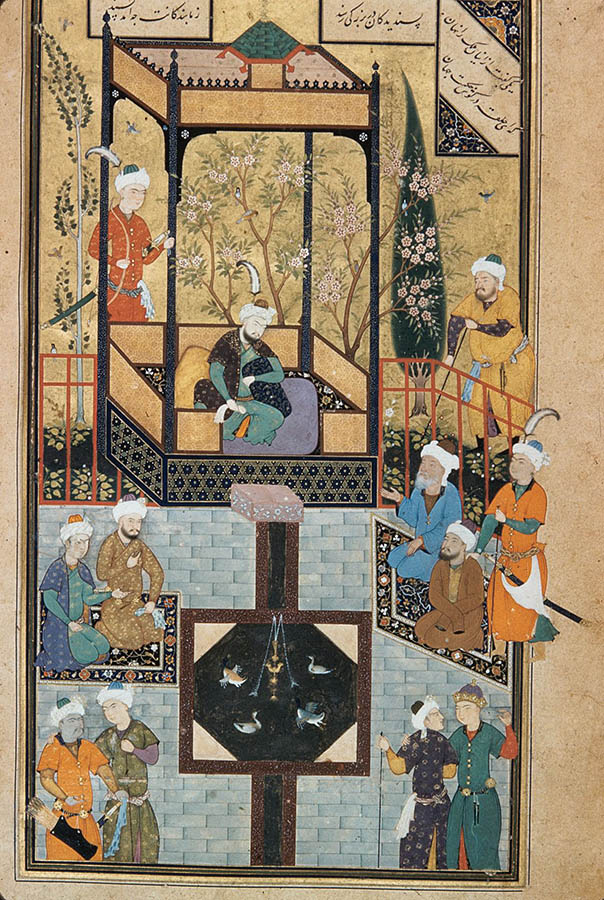

Bukhara is the city most commonly associated with the Abu’l-Khayrids, but its florescence would come later in the third decade of the 16th century under Muhammad Shaybani’s nephew, the military commander and great khan (or political head) ʿUbaydullah bin Mahmud (r. 1514–1540, first in Bukhara then Samarqand). Samarqand would remain the primary political capital throughout the first half of the century. Captured and invited Safavid artists formerly working in Safavid-controlled Herat contributed to Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts in this period, during the 1530s and through the 1550s in Bukhara [Fig. 2]. We encounter some of the finest of Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts that were made for ʿUbaydullah and his son ʿAbdul ʿAziz, who was never the great khan and, therefore, had no need to relocate to Samarqand. He was able to fully harness Bukharan talent and satisfy his appetite for books. The same workshop later made manuscripts for subsequent Abu’l-Khayrid leaders who presided over Bukhara, Samarqand, and Tashkent in the middle of the century.

Fig. 2: Garden scene from a Bustan of Sa’di, f.78v in original manuscript. Dated 1531-32 (938 AH). Painting attributed to Shaikhzada, written out by Mir 'Ali Husayni Haravi. Funding for this image is provided by the Aga Khan Program and the Stuart Cary Welch Islamic and South Asian Photograph Collection. Harvard Art Museums, 1979.20.

Bukhara finally surpassed Samarqand as the de facto capital in 1557 under ʿAbdullah Khan bin Iskandar (great khan between 1583-1598). Manuscripts were produced for him in the late 1550s through the 1570s, at which point he lost interest in book arts. These works of his patronage have a distinctive manner of execution, with figures and compositions repeated across various works of predominantly Persian poetry. The 1560s through the 1590s were fruitful and prosperous years in the Abu’l-Khayrid domain, marked by strengthened political, cultural, and commercial exchanges with India, Turkey, and Muscovy. Despite this political success, art historians have tended to only comment on the “dullness” and derivative nature of painting in Bukhara during the second half of the 16th century. But the standardisation of the third period's figures and set compositions point to a well-run workshop and access to resources to produce so many manuscripts in a short amount of time.

Later in the century, ʿAbdullah led the Abu’l-Khayrids to the heights of their political power and geographical expanse, taking the region of Khorasan from the Iranian Safavids, and Khwarazm for most of the 1590s. During his rule, ʿAbdullah gifted some of his prized manuscripts to the heads of Ottoman and Mughal states. He died in 1598, and the Abu’l-Khayrid dynasty faltered soon after.

Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts in the 20th century

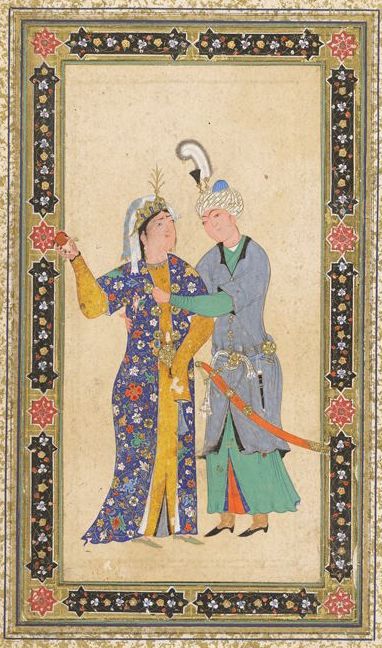

To date, Abu’l-Khayrid arts of the book have more often been swallowed up under the broader headings of “Islamic,” “Persian,” or “Iranian” that have circumscribed their analysis. (Note the couple in Fig. 3 with the amorous man and coy woman, which can hardly be labeled a devotional or religiously Islamic subject.) The Abu’l-Khayrids have been overlooked in Anglophone (as well as French- and German-language) studies of the “Gunpowder Empires,” as have Abu’l-Khayrid visual forms. Their neglect is a result of political divisions in the 19th and 20th century that separated British-controlled and post-colonial South Asia on the one hand, and Romanov (Imperial Russian) and Soviet-administered Central Asia on the other.

Fig. 3: Album painting of lovers with pomegranate. Attributed to Bukhara, circa 1560s. Gift of John Goelet, formerly in the collection of Louis J. Cartier. Harvard Art Museums, 1958.68.

Building on prior scholarship emerging in the early 1900s, the prolific British scholar on Persianate arts of the book B.W. Robinson produced a comprehensive classificatory scheme to catalogue manuscripts throughout the 1950s and 1960s [Fig. 4]. This is still used as the guide for museums and collections to label their specimens and for university courses to be structured. Art historians are indebted to the work of Robinson and others, although we are continually nuancing our knowledge of the major artistic styles associated with city names and dynasties included in his schematic, and those he left out. One such shortcoming in need of remedying is the absent Abu’l-Khayrid label in his diagram. This dynasty’s artworks are represented in the tiny designation “Bukhara style” and its painting traditions appear as mere offshoots of the broader Safavid category, in turn spawning the Mughal and Khorasan styles beneath it. But Robinson was merely following British and European typological conventions which scholars over in the Soviet Union found problematic. In contrast, academicians in the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan criticised these approaches that placed Central Asian arts under Iranian headings.

Fig. 4: Diagram of “Persian Painting” in B.W. Robinson, Persian Miniature Painting from Collections in the British Isles, London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1967. Crown Copyright operating under the Open Government License.

The geo-political and scholarly divisions that exist between Iran and Transoxiana today have their origins in the 16th century tensions between the Abu’l-Khayrids and the Safavids; the Great Game of the 19th century waged between Russia and Britain; and the later Capitalist-Socialist rivalries of the 20th century. The perceived factionalism between Iran and Transoxiana recurs in all historical periods. Degrees of Iranian influence—political and artistic—over Central Asia have long been contested, and vice versa; even in pre-Islamic polities and visual forms. Although the regions were linked in several capacities, some different and separate historical and cultural factors took place in and shaped Iran and Central Asia as in their art forms.

Historians writing in English have opted to group Abu’l-Khayrid manuscript arts under a broader Safavid heading, while Russian-speaking scholars have more stridently championed Central Asian artistic variants as local innovations independent of Iranian influence. But both reflect the politicisation and ideological dictates of academia. When 16th-century arts of the book from Central Asia are mentioned at all, many surveys published in English have forced Abu’l-Khayrid materials into classificatory schema divided by periods and schools that privilege the arts of the Safavid and Timurid dynasties, and associated these with the country of Iran. The genre of “Persian Art/Painting” was coined in the 1930s, at a time when the national, political, and cultural aspirations of Iran’s Pahlavi dynasty were merging with the personal and professional ambitions of British, European, and American scholars to bring mutual benefit. The Iranian shah Reza Pahlavi (1878-1944) was keen to exaggerate Iranian power and territorial control throughout the ages and concurrently fund and promote interest in Persian art. The Iranian nation-state at this time was, thus, partly responsible in crafting the analytical framework adopted by European and English-speaking scholars of Persian-language manuscript arts. The resulting taxonomy placed Abu’l-Khayrid materials under Timurid and Safavid headings, separate dynasties altogether from the 16th-century Abu’l-Khayrid polity in Central Asia. Other western scholars relegated Bukharan productions to the provinces and margins, and affirmed Iran as the heart and centre of a larger tradition.

Turning to the Russian-speaking sphere: in articles written in the 1950s, academicians in the Academies of Sciences in the Soviet Socialist Republics used the terms sredneaziatskii (Central Asian) and maverannakhrskii (Transoxianan; Mawarannahr implies the lands beyond the Oxus River) when treating Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts. Their adamant assertions of independence from Iranian forms and their delineation of cultural borders paralleled state messaging. Soviet scientists had an interest in promoting a rhetoric of indigenousness and regional character in their scholarship, demarcating cultural forms through difference. Despite this interest in specificity and differentiation, the Soviet Union throughout the entirety of its existence emphasised that it was the collective sum of constituent parts whereas the earlier Russian Empire of the tsar maintained the very colonial distinction between metropole and colony.

Akin to the threat of pan-Turkism, Persian-language manuscripts produced in Transoxiana also posed a similar problem of pan-Persianism/Iranism to the Soviets. Hence, scholars’ emphasis on an Iranian-versus-Central Asian divide to break up the Persian-speaking fraternity. Codices of Persian poetry that had been written out before national lines were etched onto a map. They were ambivalent and ambiguous in that they were from communities that possessed Persian cultural features or that had historical connections to cities in Iran, so could be conceptualised as part of a broader, shared pan-Persian tradition.

The shared iconographic features of Timurid, Safavid, and Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts are undeniable. Different scribes living under various dynastic administrations wrote out the same titles of Persian and Turkic poetry. Anglophone scholars were keen to promote these commonalities as components of a broader unified culture, but Soviet art historians identified distinct regional identities distinguishing and isolating 16th century Central Asia from Iran. These English and Russian-speaking researchers were writing in parallel on the same Abu’l-Khayrid dynastic arts, at the same time, in the mid-20th century. However, due to impediments of language or politics, they do not seem to have been communicating with each other at this time. Having operated in two different geo-political zones (USSR and UK) with limited porousness over the previous decades, it is understandable that these scholars came up with different classificatory schema to treat Abu’l-Khayrid painted arts. They might have reached their separate conclusions based on the materials available to them. To generalise their findings and approaches, I can state that despite the politicised tone in their writing, Soviet analysts of broader manuscript production in and around Bukhara had greater historical and contextual nuance than their British counterparts writing at the same time, though the latter possessed finer skills in formal readings and comparative approaches of art history.

Abu’l-Khayrid manuscripts today

Although dynastic borders take forms that differ from current nation-states, some dynasties get associated with national narratives more than others. Art is frequently co-opted to make nationalist and political claims of sovereignty, group affiliation, and exceptionalism. Manuscript arts of the early-modern period are no exception, and have become charged with the concerns of the modern present. All scholarship is grounded in time and place, and reflects the cultural milieu and the intellectual climate when it was written. The Islamic Republic of Iran has largely embraced the Safavid past for its promotion of Shi’ite Islam as state ideology. At the same time, Uzbekistan extols the refinement of the Timurids and its literary and cultural legacies. Yet the Abu’l-Khayrids continue to peer from the margins of history, not quite forgotten or harnessed to promote nationalistic concerns, but awaiting their day of full recognition.

Jaimee Comstock-Skipp is a Visiting Fellow at the Oxford Nizami Ganjavi Centre in the UK. Some of the contents of this contribution are taken from her forthcoming article: “The ‘Iran’ Curtain: the Historiography of Abu’l-Khairid (Shibanid) Arts of the Book and the ‘Bukhara School’ during the Cold War,” in Journal of Art Historiography, edited by Yuka Kadoi and András Barati (to be released in Issue 28, June 2023). Email: jaimee.comstock-skipp@orinst.ox.ac.uk