The Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area: Contestation among the stakeholders

<p>The various stakeholders of a heritage site will commonly appreciate it for different reasons; sometimes to such an extent that conflict and contestation occurs. This is the case at the World Heritage site <em>Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area</em>, which is not only a holy place for the Maitreya faith in China, but also a very popular tourist destination.</p>

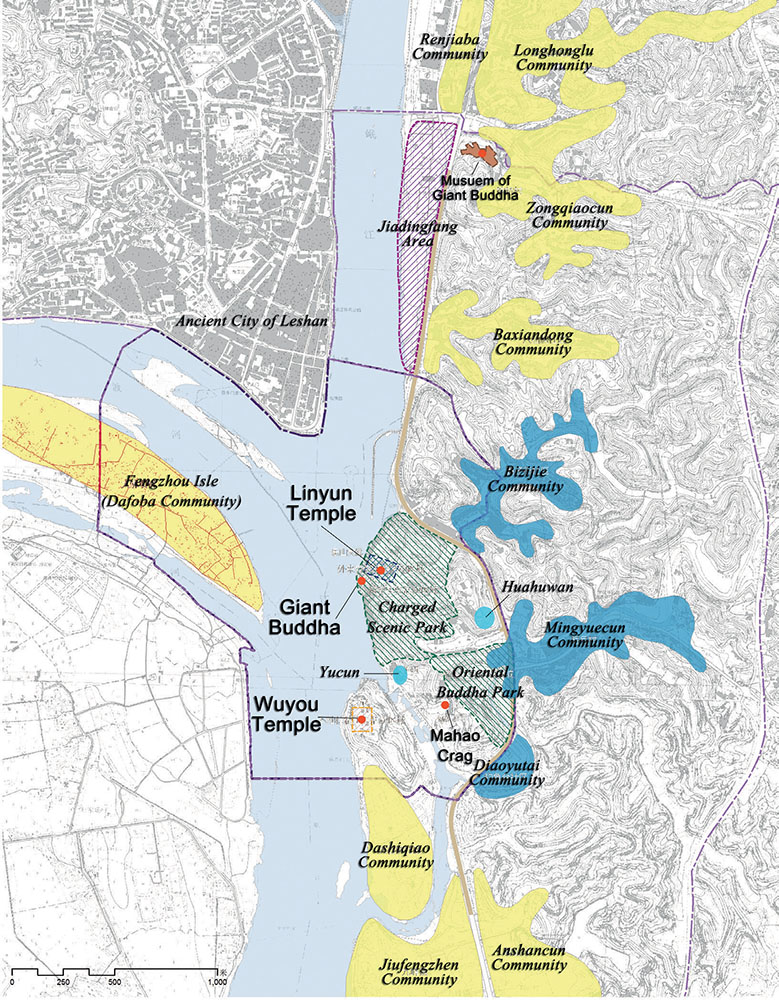

The Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area (LGBSA) in China’s Sichuan Province is a sacred site for the Maitreya faith, the main belief of the local people. It is a world heritage site (WHS) that was inscribed in 1996, together with the adjacent Mount Emei Scenic Area (MESA). At 71 metres high, the Giant Buddha is the largest Buddha statue in the world. The LGBSA is located across the river from the ancient city of Leshan, and includes a number of important protected cultural monuments in a setting of great natural beauty.

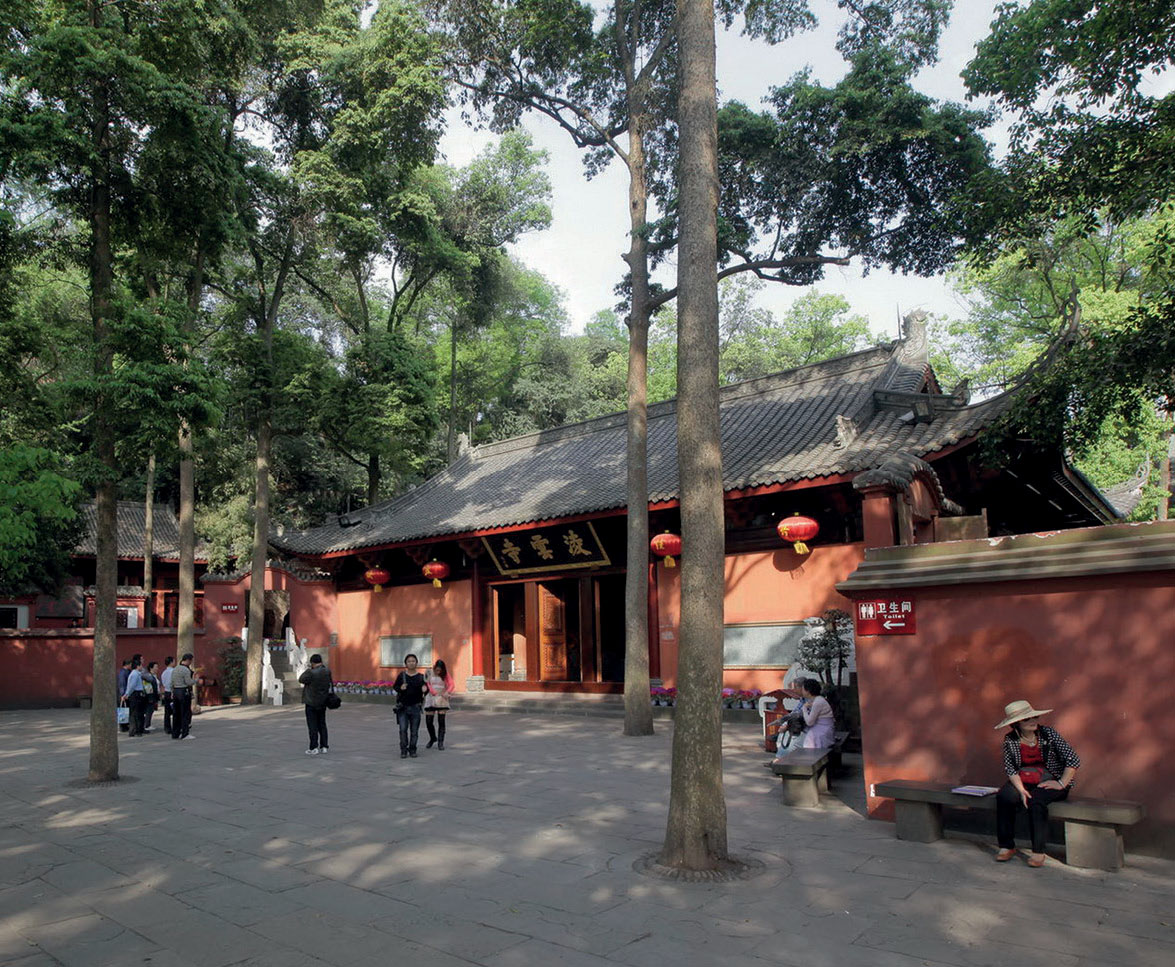

The Giant Buddha was carved out of a hillside in the 8th century, and overlooks the junction of three rivers (fig. 1). Lingyun Temple (fig. 2) stands on the cliff above the Buddha; it was first built in the 7th century, but destroyed twice between the 13th and 17th centuries. Its present structure is from the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The monks offer Buddhist services to, mainly, pilgrims who visit on special occasions each year (fig. 3). Other significant cultural structures in the area include Mahao Crag (fig. 4), a collection of over 500 tombs originating from the 1st to 4th centuries, and Wuyou Temple, an important place of worship for local Buddhists.

Incredibly, there is also a theme park called Oriental Buddha Park (OBP), situated right in the middle of this WHS, between the Giant Buddha and Mahao Crag. It is run by a private travel company, which has reproduced hundreds of famous Buddha statues found all over the world. The theme park is the second biggest attraction in the area, after the Giant Buddha itself, and many tourists pay to enter the park rather than visit other zones for free (or less). They are likely misled by all the advertising and the theme park’s obvious presence.

Conflict between local communities and the MC

Like other sacred Buddhist sites in China, Linyun Temple and its Giant Buddha statue were once local facilities. They stood in beautiful surroundings, amongst a number of small settlements, whose inhabitants would visit the temple for their daily prayers and other religious ceremonies. The local residents were fishermen and peasants; fishing the river and/or farming the land in the mountains. However, in the early 1990s, large numbers of locals were relocated, thereby losing their land. This decision to relocate was made and carried out by the Management Committee (MC) of LGBSA, established to take charge of the WHS application in 1996 and currently the executive of the LGBSA.1 . 资源开发与市场12:1141-1143)] The committee’s main concerns are the preservation of the inscribed cultural heritage and the investment in tourist services to bring money to the area, rather than the personal needs of the local people.

Bizijie is a community of 1244 households, located right at the main entrance of the LGBSA. Its name literally means ‘comb street’, indicating its original layout that is typical for a traditional Chinese village: a main street with branching alleys. The village used to be bigger, but many residents were relocated. The compensation was very low, and certainly insufficient. Those who remained lost their farmland and had to turn to other ways to make money, such as tourist services like snack bars, restaurants and souvenir shops. The revenue was at first not bad because of the village’s prime location at the entrance of the WHS area, but in 2004 a travel agency was established, under the supervision of the MC, which monopolised the local tourist business and isolated Bizijie from the tourist route by building blocks in the middle of the road between the community and the Scenic Area. Even though the blocks were dismantled a few days later, the conflict had taken hold and the locals lost their trust in the MC.2 . 四川烹饪高等专科学校学报4:39-43)] Most of the remaining residents gave up and moved out of the area, leaving all tourist business to be run by outsiders with little to no knowledge of local history, and who are not even Buddhists.

Another example of conflict between the MC and locals has taken place at the village Yucun. Yucun literally means ‘fishing village’; its 40 households used to make a living by fishing the rivers. Before the 1990s, all visitors to the Giant Buddha arrived by boat and walked through the village to the statue. However, in the 1990s the MC decided to reconstruct the village, and temporarily moved the inhabitants to Diaoyutai. They were promised they could soon return, yet this has still not been made possible. Currently Yucun is no longer a settlement, but just a street with restaurants, tea houses and souvenir shops. To be fair, the owners of these establishments are amongst the original inhabitants, but business is disappointing. The route to the Scenic Area has been diverted and tourists no longer pass through Yucan on their way to the Giant Buddha. The revenue is no more than basic living expenses, as one of the owners told us.

These are not the only examples in the area of people who have been forced to move. Many more have lost their land due to land expropriation by the MC. The compensation is minimal and they have not been given priority to employment by MC’s travel agency, even though most positions are non-technical and low-paid, such as cleaners and guards. Most of the young people have had to find work in other towns and cities. Ironically, the private travel agency running the Oriental Buddha Park is regarded in a more positive light by most locals. The OBP agency has also expropriated some farmland and has relocated residents, but it pays a higher compensation, many of the relocated people are hired by the travel agency afterwards, and all the residents get pension insurance – the three main concerns of relocation are much better dealt with by the OBP agency than by the Heritage MC.

Buddhist sanctuary or touristic destination?

The Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the LGBSA,3 stated by UNESCO, lies in the unique landscape at the confluence of three rivers, the technique of constructing the Giant Buddha, and the testimony of the historical development of the Maitreya faith in China. The inscription of World Heritage Site attracts an immense amount of attention. In the questionnaire,4 93% of the interviewees know of the site, though only 11% have been there. The number of visitors has been increasing steadily, reaching 3 million in 2012. However, the tourism boom seems to be overwhelming the sacredness of this Buddhist site.5 . 企业科技与发展 23:51-55)]

There are two temples at LGBSA, Lingyun and Wuyou, where religious services are offered by the same group of monks. Both temples used to be thriving and bustling on the 1st and 15th day of each month when hundreds of locals came to light incense and to pray. The temples have different users now, mainly because of their respective locations. Locals only go to Wuyou Temple, as an entry fee is charged at Linyun. Linyun is always full of tourists whose main destination is the Giant Buddha. Most visitors offer incense, even though they are not necessarily devout followers, and many pilgrims are attracted by the reputation of the temple. The monks thus benefit from the fame of the World Heritage Site, and would now like to enlarge their temples and improve their living and work conditions. However, their plan has been refused by the MC, as the temples are important features of the WHS, situated right in the middle of the Scenic Area, where new construction is forbidden. In this case it seems that heritage protection is being given priority over religious demands, even though the religion is essential for the heritage value. However, the MC’s consideration may in fact lie with wanting to follow the WHS ‘rules’, as the inscription brings with it tourism and income for the local economy.

Based on the outcome of the questionnaire.6 the visitors’ appreciation of this heritage site is quite ambiguous. They agree with the OUV of the area, yet most visitors fail to see or understand the many cultural and historic aspects of the site. Their schedules are often tight, and they are commonly given just half a day by the travel agency to explore the Scenic Area. The main attraction is the ‘hugeness’ of the Giant Buddha, and the impressive landscape, yet little to no attention is given to understanding the history of the Maitreya faith or experiencing the local culture. The fact that the average tourist is denied the full experience of local religious performances and daily activities, potentially impairs their better understanding of the heritage values of the World Heritage Site.

Whose heritage?

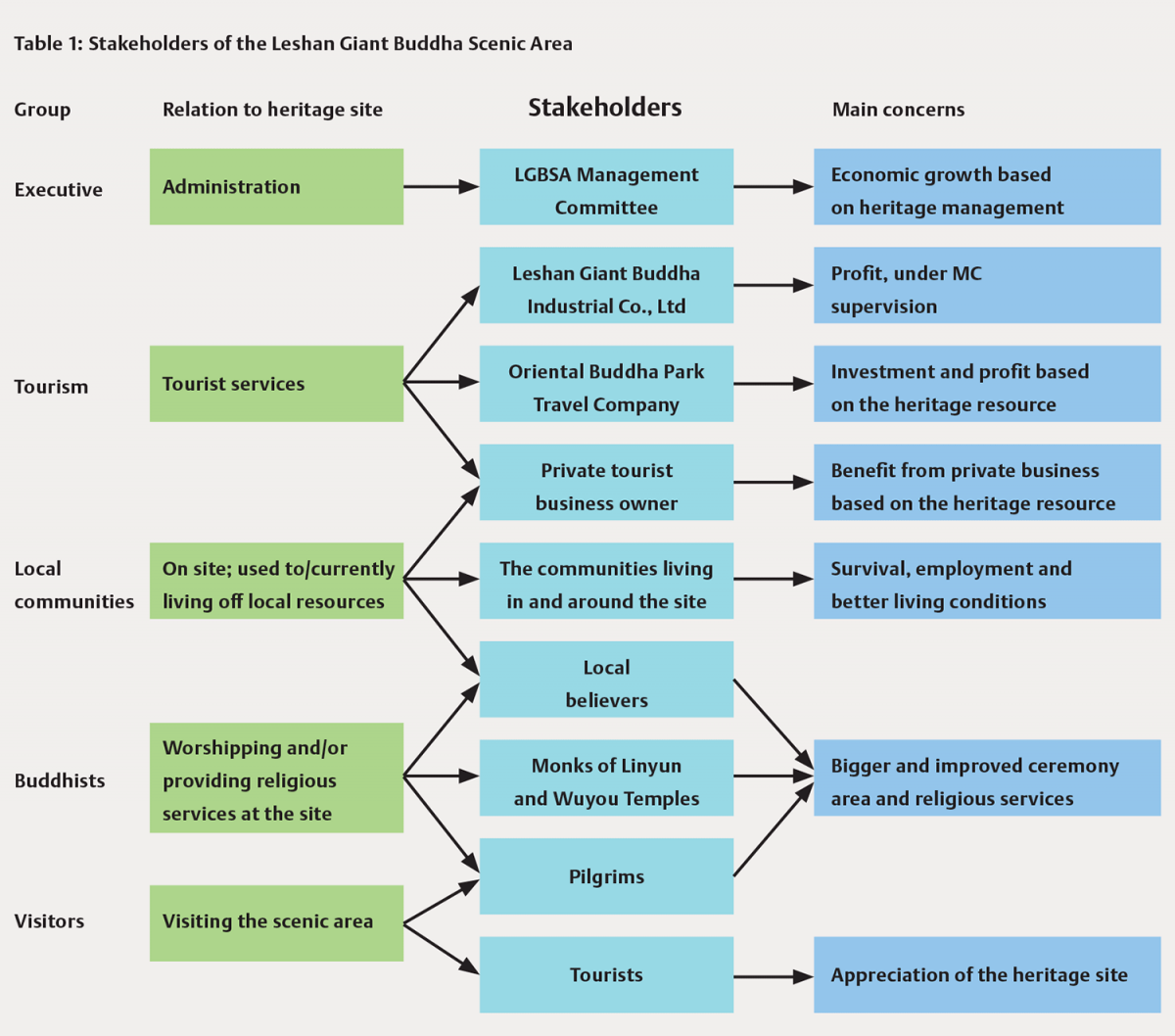

There are different stakeholders of the Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area, dividable into several groups according to relation to, and main concern with, the heritage site (table 1). Their demands often conflict with one another.

Table 1: Stakeholders of the Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic AreaGroup | Relation to the heritage site | Stakeholders | Main concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

Executive | Administration | LGBSA Management Committee | Economic growth based on heritage management |

Tourism | Tourist services | Leshan Giant Buddha Industrial Co., LTD | Profit, under MC supervision |

Oriental Buddha Park Travel Company | Investment and profit based on the heritage resource | ||

Private tourist business owner | Benefit from private business based on the heritage resource | ||

Local communities | Living at site; used to/currently living off local resources | ||

The communities living in and around the site | Survival, employment and better living conditions | ||

Local believers | Bigger and improved ceremony area and religious services | ||

Buddhists | Worshiping and/or providing religious services at the site | ||

Monks of Linyun and Wuyou temples | |||

Pilgrims | |||

Visitors | Visiting the scenic area | ||

Tourists | Appreciation of the heritage site |

Besides functioning as an authority, with economic growth as its primary task, the MC is also guided and limited in its actions and policies by the official OUV. The Outstanding Universal Values need to be met before being inscribed on the World Heritage List; the 6 criteria for ‘cultural heritage’ have been determined by UNESCO and its advisory institutes. Although it’s an open framework, the OUV are still defined by the authorities, who have clearly given priority to the on site ‘monuments’, with less concern for stakeholders, their understanding of the heritage site, and their demands. It is indeed common at WHS, especially at living heritage sites of significant religious value such as the LGBSA, that the tangible heritage (mainly monuments and buildings) is the only object of conservation and periodic monitoring by international authorities, while the associated intangible traditions and beliefs, which have close links with their stakeholders, are often neglected.

The LGBSA has been valued as a masterpiece of great originality and ingenuity (criterion iv) and as directly associated with the living tradition of Buddhism (criterion vi). In direct accordance with WHS rules, the MC only takes great care of the various inscribed heritage elements on the site, rather than the integral development of the whole heritage site.

The Giant Buddha and its associated religious facilities are the main monuments, and are considered to be the main touristic resources. The problem is that the MC fails to find other ways than heritage tourism to develop the area; other local resources (such as the local culture and surrounding natural landscape) are out-performed by the main monuments, and have little significance for the MC development plans. The local belief, which is an indispensable part of this Buddhist site, is given little attention simply because it isn’t able to bring in money.

The MC has worked hard to ensure no changes are made to the monuments, thus safeguarding the tourism business, even though the changes could in fact revitalize the religion. The local people are given even less concern. The Scenic Area used to be their living space, and they are the most able to interpret the heritage values of their Maitreya faith. Yet the conservation approach in use is certainly not human-based, and serves neither as a way to continue the local beliefs, nor to enrich people’s lives, even though the heritage site used to be all theirs, before becoming universal ‘heritage’.

Xiaomei ZHAO, lecturer at Fudan University, affiliated researcher at Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, and research fellow at IIAS. Her research interests include conservation of built heritage, heritage management and architectural history (zhaoxiaomei@fudan.edu.cn).