Laos: The Long View

Meet the author

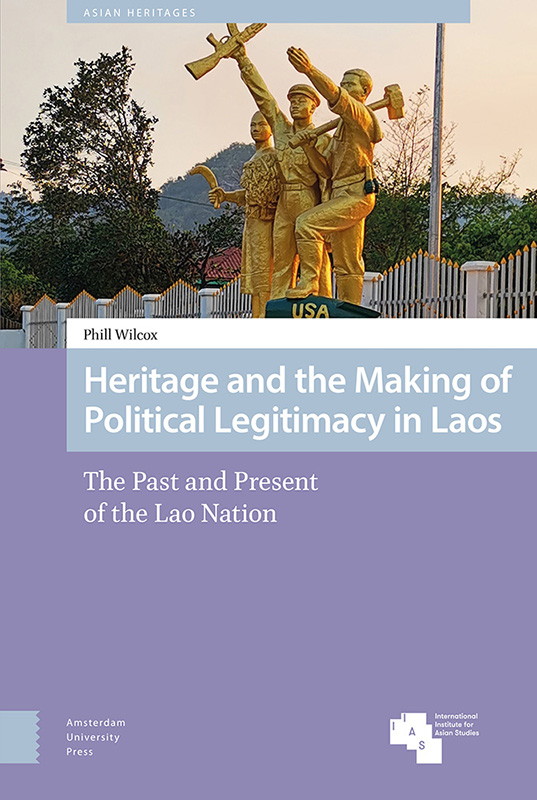

For IIAS Publications, we invite authors who have recently published in the IIAS Publications Series to talk about their writing experiences. What inspired them to conduct research? What did they encounter in the field? What are the stories behind their book? This edition features an essay by Phill Wilcox, author of Heritage and the Making of Political Legitimacy in Laos: The Past and Present of the Lao Nation.

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic celebrated its 46th birthday on 2 December 2021. The political system in Laos is now comfortably middle-aged. I first went to Laos in 2002, as a much younger person and at a time when the Lao political system was a youngish 27 years old. Much has changed, and stayed the same, in the last two decades.

Taking a long view of Laos encourages me to think about Laos as I first encountered it. Of course, I was aware of its former royalist administration and the events that led to the founding of the country as a one-party socialist state in 1975. My mother had been assigned to Laos in the early 1970s as a British Council worker, leaving shortly before the revolution. When I first encountered Laos myself in 2002, I wondered how the Lao people understood and perceived their political system. What is it like to live under such a system in the contemporary world? I was also struck by the question of why the one-party system had endured in Laos, when similar regimes had fallen all over the world with the dissolution of the USSR. When we talk of political transition, we talk of transition to what exactly, and is this always an inevitable, linear process ending with some sort of capitalist democracy? These questions are the backbone of the research that has taken me to Laos again and again.

After that first visit, I returned to the UK, graduated, and settled into a job in refugee law. I never advised anyone from Laos, but I encountered many from similar political systems. Over the following decade, the political climate towards legal advice and refugees hardened, and I began to consider other possibilities. As my interest in Laos had never gone away, I had started to travel to Laos most years from about 2007 onwards. I decided to convert this interest in Laos into actual research, registering for a Master’s degree and, later, a PhD with a very supportive and encouraging supervisor. My entry point into research was one of finding a location and research theme and then applying for formal academic study, rather than the other way around. Along the PhD journey, I was also very fortunate to have the opportunity to study Lao at the Southeast Asian Studies Summer Institute at the University of Wisconsin in the summer of 2014. By this point, I realised that a considerable number of people believed in me and my research trajectory, and I returned to Laos for my PhD fieldwork in 2015.

I spent over a year in and around Luang Prabang, the former royal capital, the largest city in Northern Laos, and the cultural centre of the country. This time coincided with the 40th birthday of the current political system, and 25 years of Luang Prabang as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I learned a considerable amount about my topic and wrote in my thesis, and latterly in my book, about how selective representations of the past feed into narratives of the national story of contemporary Laos. Overwhelmingly, I met many people for whom the revolution was an event that happened several generations before them. While many know that their political system is different from that of, say, Thailand, it has delivered stability in a very poor country. Many people expressed a need for better infrastructure and development in Laos, but nobody told me that political reform was a prerequisite to achieving that. I also learned to take what the Lao state says about itself seriously. Outsiders may well conclude that it is neither socialist nor a democracy, but in official terms, socialism remains part of everyday discourse and a destination the country will arrive at one day. This explains why the term “post-socialism” is unhelpful in Laos. Similarly, the Lao political establishment claims to be the legitimate representatives of the Lao population, even though the country is a one-party state..

I wanted to understand more about what it is to be a citizen of the contemporary state of Laos, and how different people are included, or alienated, from the political establishment in its different forms. To put this in a slightly different way, I wondered how, where, and why different people encountered the state and vice versa. As it happened, many of my friends and associates in Laos are Hmong, one of the country’s largest ethnic minorities. The Hmong make up around 10% of the overall Lao population and face discrimination at all levels of Lao society, largely on the basis of widespread Hmong opposition to the establishment of socialism in 1975. The effects of this have very real consequences in contemporary Laos. I witnessed this myself shortly after commencing my PhD fieldwork when a young Hmong friend and I were stopped by the police and fined for a minor infraction while travelling on his motorbike near his village. Later, I asked my friend why he felt that we had been stopped when other vehicles were allowed to pass without any problem. He responded that he knew that he had been stopped because he is Hmong.

But while patterns of discrimination repeat themselves, I also became aware that such young people were forging new futures in a changing Laos. Many still learn English, but an increasing number also study Mandarin and regard China as a place of opportunity, where one can study at university and later gain a well-paid job with one of the growing number of Chinese companies in Laos. One young person even went as far as to explain this to me in overtly colonial terms: he was learning Mandarin for the same reason older generations of his family had learned French. Initially, I viewed the growing amount I heard about China as something interesting, but unrelated to my research. Such a position did not last and now seems embarrassingly naïve. I began to understand that if China was key to how my Lao friends and associates understand and locate themselves in contemporary Laos, then it should be important to me, too.

I took this change of direction head-on and began to think about China not as a peripheral interest, but something much more significant. I devote a chapter of my monograph to it and am now researching perceptions of China in Laos specifically. Back in 2002, I travelled from Vientiane across the Chinese border, a bone-shaking journey that took several days on multiple buses. Coincidentally, this was a border about which I would later spend much time thinking. I also repeated this journey in the other direction in late 2017, having travelled to visit a group of Lao students at university in a minor city north of Shanghai. Fifteen years after my original encounter with the Laos-Chinese border, transport possibilities had much improved and will become quicker still with the opening of the Laos-China high-speed railway line in December 2021. Once the border reopens, this new infrastructural project will cut the travel time down from days to mere hours. Here, I can see the concern about improved access to Laos from China as a tangible reality. I am also struck by how my Lao friends regard China as a contradictory force, representing both opportunity and anxiety simultaneously.

Much has changed in Laos in the 20 years since I first encountered it, and one advantage of having thought about Laos for nearly two decades is the ability to do what Jonsson aptly termed slow anthropology 1 . I very much appreciate the long view, the context, the getting to know Laos in different ways over many years, even before I formally started to be there as a researcher. Equally, there is no “before” and “now” as fixed points in time: Laos was in a state of change in 2002, much as it is now. Some of these changes, most notably the rising visibility of China in Laos, have happened rapidly in the last decade. Other changes are longer and slower in the making. For me, the most interesting thing is that the authoritarian system endures. It shows no sign of disappearing anytime soon, and it shows remarkable ability to change shape. From leading economic changes in Laos in the mid-1980s to reinventing itself as the legitimate guardian of Lao culture and society in the early 1990s, the system has managed to embed itself and remain relevant to the lives of much of the population. If anything, it may be in the process of changing shape again, as Chinese influence embeds itself in the literal and metaphorical landscapes of Laos.

I am delighted to have published my monograph on Laos, which represents the culmination of this part of my long interest in the country. At the same time, I also believe that I have many more questions than answers. My interest in the Lao political establishment and, more importantly, how it is understood and interacted with, remains. It is also the foundation for all the work I have done (and continue to do) since. My book concludes with a suggestion that the rising influence of China in Laos may prove the ultimate test of Lao authorities.

Dr Phill Wilcox, Faculty of Sociology, Bielefeld University. E-mail: phill.wilcox@uni-bielefeld.de

Phill Wilcox will give an online IIAS Book Talk on 7 April 2022, at 14:30 (CET). For more information, please visit www.iias.asia/events/heritage-and-making-political-legitimacy-laos.

For more information on IIAS books, please visit www.iias.asia/books