Language, power and identity in Asia: creating and crossing language boundaries

From 14-16 March 2016, the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the Netherlands, was the venue of a large international conference on the role of languages in Asia. The conference was co-sponsored by the Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, the Leiden University Institute for Area Studies, and supported by LeidenGlobal. Organised by IIAS, the meetings were attended by almost two hundred participants from all over the world. All together they presented almost 150 papers (35% from Asia, 37% from Europe, 10% from the USA, and the remainder from Russia, Australia, the Middle-East and Africa). These contributions, which discussed a multitude of approaches and covered a wide geographical area, centred on the importance of linguistic differences, practices, texts and performances and their impact on the political, social and intellectual power structures among Asian communities, both in the past and in the present.

Keynotes

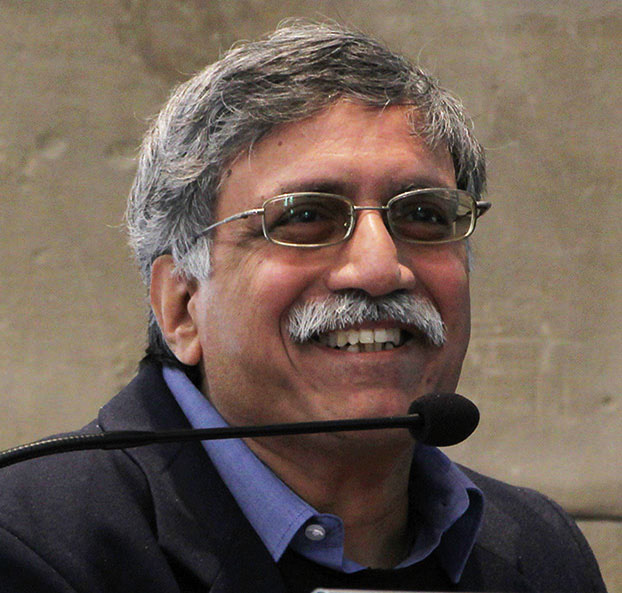

The conference was introduced by two keynote speakers: Professor G.J.V. Prasad (Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Advanced Study in New Delhi, India) and Dr Mark Turin (Chair of the First Nations and Endangered Languages Program and Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, Canada).

Prasad in his talk addressed the role of English as the Associate Official Language of India, and its contested position with regard to Hindi, the Official Language. He argued that Indian multilingualism and identity politics, together with the impact of globalization, have made the position of English in India almost unassailable. Turin in his address focused on the hierarchies of language and power in the Himalayas, in the face of growing vulnerability of many of the Himalayan languages, caused by mobility and migrations and cross-border resource conflicts. Although linguistic rights may now often be protected by legislation, there is sometimes an unsurmountable gap between political aspiration and effective implementation.

Parallel sessions

Following the keynote addresses, the participants joined a series of 42 parallel sessions that all focused on different sub-themes. These parallel sessions included three to five speakers who briefly outlined their paper, after which the floor was opened to often very lively and animated discussions, which were continued over coffee and lunch. It is of course impossible to list all panels and contributors here, but the programme and all abstracts are available on our website.

There was much attention given to the linguistic situation in the Indian subcontinent, but also on mainland Southeast Asia, the Indonesian archipelago, and East Asia. Some of the panels had been organised by the contributors themselves: for instance, ‘Harmonisation of territorial nationalism with cross-border languages reservoir for peace building (A case of South Asia)', organised by Pramod Kumar (Institute for Development and Communication in India), and ‘Language, power, discourse and identities in China’, put together by Linda Tsung (University of Sydney, Australia). Equally interesting and important were panels such as, to name but a few: ‘Rethinking the relationship between language and identity in Burma and beyond’, ‘Localised terminologies, political implications’, ‘Language and hierarchy’, and ‘Languages and practices of imperial power in local government of Kazachstan’.

Part of a panel focusing on the politics, identity and power in South Asia was a presentation by IIAS fellow Bal Gopal Shrestha, entitled ‘‘Nepali’, the official ‘killer’ language and other Nepalese languages in multi-lingual Nepal’. In his presentation, Shrestha focused on the position of the language of the Newars (‘Nepal Bhasa’), the indigenous people of the Kathmandu Valley and surrounding areas. Nepal, a multinational, multicultural, multilingual, and multi-religious Himalayan country in South Asia, hosts more than 100 ‘nationalities’ or ‘ethnicities’ (janajati), speaking various languages and dialects. As a result of the 1769 Gurkha conquest, Nepal underwent a repressive rule of ‘one-language - one dress, one nation - one country’ for about two and half centuries, to the benefit of the ruling Arya-Khas or the high caste Hill Brahmins and Chetris, who speak Khas as their mother tongue. The suppression of Nepalese languages was systematically applied during the later period of the Rana regime (1846-1951) when the rulers desired to make their mother tongue Khas, also known as Parvate or Gorkha bhasa, the single official language of Nepal, designating it as ‘Nepali’. As a consequence, the Newars lost the true name of their language ‘Nepal Bhasa’. The Newar language was officially banned from the court, and sanctions were imposed on the usage of the Newar language. Many Newar writers were given admonitions and fines, sent to prison or forced into exile. The new constitution of 2015 still fails at recognizing equal status to all the languages spoken in Nepal and gives continuity to the discriminatory policy favouring a single language – ‘Khas’ – as the only ‘Nepali’ and ‘official’ language of Nepal, much to the dissatisfaction of various indigenous nationalities, such as the people of the southern plain (Madhesi), indigenous nationalities (Janajati) and the Tharu, who have been fiercely protesting the new constitution.

These are just a few examples of the many interesting panels and presentations held over the course of three days. The facilities of the Museum and that of the adjoining Gravensteen, where some of the panels were held, ensured a very congenial atmosphere that strongly contributed to the exchange of knowledge and ideas.

The programme and all abstracts are available at: www.iias.asia/language