The Kolkata (Calcutta) Stone and the bicentennial of the British Interregnum in Java, 1811 - 1816

<p>The bicentennial of the British Interregnum in Java (1811-1816) provides the occasion to contemplate a lost opportunity to right some of the wrongs perpetrated by Sir Stamford Raffles and his light-fingered administration. Salient here is the fate of the two important stone inscriptions – the so-called ‘Minto’ (Sangguran) and ‘Kolkata’(Pucangan) stones – which chronicle the beginnings of the tenth-century Śailendra Dynasty in East Java and the early life of the celebrated eleventh-century Javanese king, Airlangga (1019-1049). Removed to Scotland and India respectively, the article assesses the historical importance of these two inscriptions and suggests ways in which their return might enhance Indonesia’s cultural heritage while strengthening ties between the three countries most intimately involved in Britain’s brief early nineteenth-century imperial moment in Java: India, Indonesia and the United Kingdom.</p>

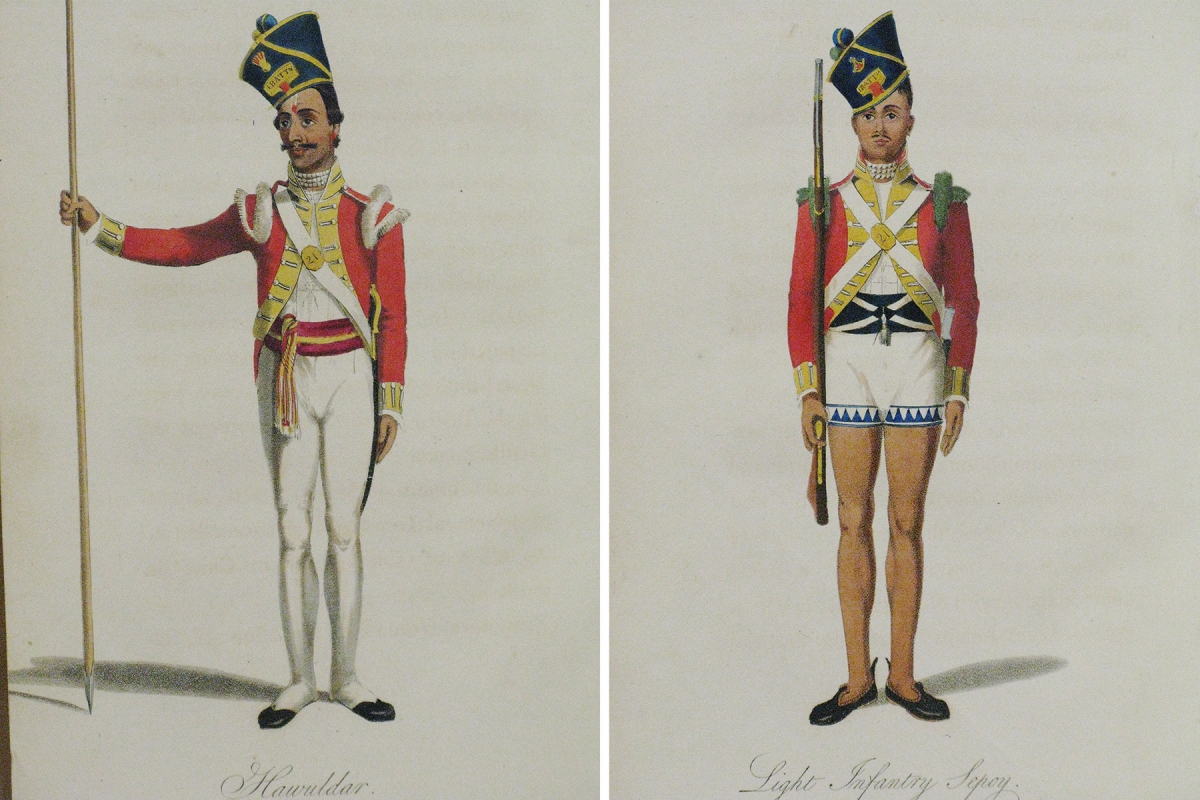

On 4 August 1811, a 10,000-strong British expeditionary force, composed mainly of Indian troops (sepoys) principally from Bengal, but with a handful of specialist troops (horse artillery and sappers) from the Madras (Chennai) Presidency army, invaded Java to curb the expansionist plans in the Indian Ocean of the Emperor Napoleon (reigned 1804-1814, 1815). Through his military appointees, Marshal Herman Willem Daendels and Lieutenant-General Jan Willem Janssens, who had served successively as governor-generals of Java between January 1808 and September 1811, Napoleon had instituted a Franco-Dutch Government in Java.

The British force landed at Cilincing just to the northeast of Jakarta (then Batavia) and swiftly captured the old town (Kota) of Batavia (8 August). Just over a fortnight later they stormed Daendels’ great redoubt at Meester Cornelis (Jatinegara) (26 August), a bloody victory which took a heavy toll on the defending Franco-Dutch who suffered more than fifty percent casualties (12,000+ out of their 21,500 troops enlisted were killed during the course of the six-week campaign), a death toll forever commemorated in the Jakarta place name – ‘the swamp of the corpses’ (rawa bangké) – where the British flung the dead from the Cornelis battlefield.

The Governor-General of India, Lord Minto (in office, 1807-1813), who had accompanied the expedition from Kolkata in part to use his Masonic connections to ensure a swift political rapprochement with senior Dutch inhabitants,1 immediately issued a proclamation. This promised the inhabitants of Java a new era of enlightened government. Meanwhile, Minto’s protégé, Thomas Stamford Raffles, formerly Secretary (1807-1810) to the Pinang Government, was appointed (11 September) Lieutenant-Governor (in office, 1811-1816), marking the beginning of what is commonly referred to as the British Interregnum (i.e., interim administration) in Java.

It might have been expected that the 200th anniversary of the victory of the British-Indian force at Meester Cornelis and the establishment of Raffles’ five-year interim administration, would have been the occasion for a number of ceremonies and historical memorial events, providing an opportunity for the staging of exhibitions and conferences focussing on the British period in Java. The humanitarian reforms of Minto and Raffles, in particular Minto’s abolition of slavery and judicial torture under the terms of the 1807 abolitionist legislation, might have been celebrated in such a bicentennial, and this in turn might have helped to strengthen Anglo-Indonesian relations and quicken an interest in Indonesian history and culture. Sadly, none of these expectations have come to pass. There is seemingly no interest in the history of the short-lived British Interregnum in Java either on the part of the British or the Indonesians. This is strange indeed given that Indonesians daily experience the long-term effects of the British occupation by driving on the left and buying snacks from ‘pedagang kaki lima’ (‘five-foot’ food peddlers – the number referring to Raffles’ instruction that all pavements should be five-foot broad). This year, on 19 August 2016, the 200th anniversary of the formal return of Java and its dependencies to the Dutch, the bicentennial will have passed.

India’s contribution during this period was crucial for without the presence of the Bengal and Madras troops, who constituted two thirds of Minto’s force, the British could never have undertaken such a bold military operation. Furthermore, it took place under the aegis of the British East India Company and was coordinated by the Company from its seat of governance in India in Calcutta (Kolkata), hence Minto’s presence in the expeditionary force. Many of the Bengal and Madras troops remained in Java throughout the period of Raffles’ government and some even beyond that: the Indonesian national hero, Prince Diponegoro’s (1785-1855), personal physician was an erstwhile Bengal Muslim sepoy, and former Bengal Presidency Army troops fought on both the Dutch and Javanese sides during the Java War (1825-1830).2 The fact that the entire island of Java had been pawned by the returned Dutch colonial government in 1824 for a 300 million Sicca Rupee loan (₤2.000.000.000 in today’s money) on a private Kolkata bank, Palmer & Company, made the bank’s owners particularly anxious not to lose their investment – hence the offer of Bengal sepoys to the beleaguered Dutch.3

In October-November 1815, some forty years before the great Indian war of independence of 1856 – known to the British as ‘The Indian Mutiny’ – and nine years after the Vellore (Arcot) Mutiny of 10 July 1806, Bengal soldiers stationed in south-central Java staged their own insurrection. Inspired by the Hindu-Buddhist rituals of the Surakarta court and the remains of Java’s great temple structures at Prambanan and Borobodur, they planned to kill their British officers, destroy the foundations of European power in Java and institute their own Bengal sepoy administration with one of their Junior Commissioned Officers (JCOs) as the new Governor-General.4 It might thus have been especially appropriate for the bicentennial of the British Interregnum in Java to be celebrated jointly by its three principal participants: Indonesia, India and Britain.

Proposed restitution of the ‘Kolkata Stone’

The Javanese king Airlangga (reigned, circa 1019-1049), is a well-known and much loved figure in Indonesia. He has even been compared to the Pandawa hero Arjuna in 11th-century court poet Mpu Kanwa’s famous kakawin (Old Javanese court poem), Arjunawiwāha (‘The Marriage of Arjuna’), the very prototype of Javanese classical poetry. By attaching to his lord and sovereign the timeless qualities of the sage-hero, the poet ensured that Airlangga’s reign would serve as an outstanding example for his royal descendants.

Such is the mythical aspect. For an accurate historical account of Airlangga’s reign we are dependent upon a large inscribed stone bearing the Śaka date 963, equivalent to 6 November 1041. Known to historians as the charter of Pucangan, this inscription is unique in that it is the sole known documentary source that provides both a chronological account of Airlangga’s achievements, and a clear genealogy stretching back four generations. Inscribed in two languages (Sanskrit and Old Javanese), the charter describes the destruction of the kingdom ruled over by Airlangga’s predecessor, Dharmawangsa (d. 1016), and the sixteen-year-old Prince Airlangga’s subsequent retreat into the wilderness to undergo a period of severe asceticism. This was then followed by his consecration as king and a seven-year struggle to re-unite the land of Java. In short, the inscription provides us with Airlangga’s life story. Without it, we would know almost nothing about the details of this remarkable king’s reign. Ironically, however, this valuable item of Indonesian cultural heritage is not readily accessible to those for whom it holds the greatest value since it is currently housed in the Indian Museum of Kolkata. For that reason, it has come to be known as the ‘Kolkata [Calcutta] Stone’; an object about which Indonesian schoolchildren are familiar only by name.

Exactly how and when the charter of Pucangan found its way to Kolkata is not entirely clear. All that we know is that it is one of two important Javanese stone inscriptions that were sent to India during the period of Raffles’ administration. Both stone inscriptions were collected by Colonel Colin Mackenzie (1754-1821), chief engineer officer to the British-Indian forces in Java (1811-1813) and subsequently Surveyor-General of Madras (1813-1821), during his brief sojourn in eastern Java early in the year 1812. Concerning the discovery of these inscriptions, we have the following information.

The 10th-century stone of Sangguran was removed from the hill region of Malang and shipped to Kolkata on the East Indiaman Matilda in April 1813, as a gift from Raffles to his patron, Lord Minto. Minto ended his term of office in December of that year and took the stone home with him to Scotland, where it was placed at his ancestral seat in Roxburghshire in the Scottish borderlands. There it has remained to this day, and is popularly known as the ‘Minto Stone’.

As for the Kolkata Stone, we know even less, as the precise details of its discovery and shipment still remain uncertain. It seems probable, however, that Mackenzie came across it during an excursion to the region of present-day Mojokerto/Jombang in March 1812, and had it transported to Surabaya by way of the Kali Mas river. The details of its shipment to Kolkata are as yet unknown, but the inscription was quite conceivably among the items that accompanied Mackenzie on his return to India in July 1813 on the Matilda.

Raffles showed a keen interest in the history of Java and instructed Mackenzie to search for “well preserved specimens of the country’s ancient letters”; a mission which the latter fulfilled with admirable zeal. What neither Raffles nor Mackenzie could possibly have known at the time, however, was that the two ‘well preserved specimens’ procured by Mackenzie in 1812 were unique historical documents in their own right. Indeed, it was not until the early 20th century that the contents of both inscriptions were published in their entirety, and it was only then that their importance for our knowledge of ancient Javanese history became apparent.5

The ‘Minto Stone’ is the last known recorded document issued by the Śailendra rulers of ancient Mataram (8th-10th centuries), while the ‘Kolkata Stone’ provides detailed information about the King Airlangga, hitherto known only in myth and legend. Taken together, both inscriptions have helped to establish a coherent chronology linking two important historical periods. Whereas the Sangguran inscription refers to the prince named Sindok, who was to found a new dynasty in eastern Java in the year 929, after the move of the Śailendra monarchs from central Java, the charter of Pucangan was issued to commemorate the re-unification of Sindok’s kingdom by his great-great-grandson, Airlangga.

Comparing the fates of these two important stone documents, it would seem that the ‘Minto Stone’ has fared slightly better than its counterpart in India. The first Earl of Minto, after all, was true to his word and – although he died on his way home (at Stevenage, Hertfordshire, 21 June 1814) – saw that the inscription was taken to his ancestral seat in Roxburghshire, following Mackenzie’s advice: “On the banks of the Teviot [the inscription] might some day afford to British Orientalists an object of pleasing and useful speculation of Asiatic Literature .....”. At the very least, it shows that Minto valued the item and took the trouble to have it transported to his estate in Scotland, despite the fact that it weighed more than three tons. The ‘Kolkata Stone’, on the other hand, was stored in the Indian Museum where it is now almost forgotten. If the former Governor-General had expressed his hope that the gift from Mackenzie might “at some day tell eastern tales of us”, the only tale that the ‘Kolkata Stone’ can tell is one of apathy and neglect.

In reality, of course, the present position of both stones is inappropriate. One – the Minto Stone – has been reduced to the status of a garden ornament in a remote and barely accessible border region of Scotland, while the other has suffered a degraded existence as a minor curiosity trapped in the godown of a foreign museum as though by historical accident. The clarity of its inscription has also been severely degraded by the current deplorable conditions in which it is kept as we can see from the recent photograph taken by the Leiden-trained Sanskritist, Professor Arlo Griffiths, currently of the École française d’Extrême Orient, in January 2011.

The current Lord Minto (VII), who is the legal owner of the Sangguran charter, has for some years been aware of the importance of his unique heirloom inherited from his ancestor. He wholeheartedly supports the idea of the ‘Minto Stone’s’ repatriation. It would be a fine thing if this spirit of generosity found its echo in a sympathetic gesture from the Indian Government. In this way two outstanding Indonesian national treasures could return home after 200 years in exile, to be enjoyed and appreciated by the descendants of the people for whom they were initially erected in early medieval Java. The placement of both stones in the National Museum of Jakarta, through the joint participation of the three major participants in the British Interregnum in Java: Indonesia, India and Britain, would surely be a fitting way to mark the bicentennial. Even if such a return cannot be negotiated in time for the end of this 200-year commemoration on 19 August 2016, one possible intermediate step would be for a temporary loan of both these stone inscriptions to be contemplated by the Indian Government and the Minto trustees respectively. In this fashion a vital part of Indonesia’s pre-colonial history can be restored.

Nigel Bullough (Hadi Sidomulyo) is an independent researcher domiciled in Bali who has since 1972 written on the pre-colonial history and culture of East Java. In November 2015, Nigel won the prestigious Borobodur Writer's Sanghyang Kamahayanikam Award for his lifetime achievement, in particular his recent researches on Majapahit archaeological remains on Mt Penanggungan (hadisidomulyo@hotmail.com).

Peter Carey Fellow Emeritus of Trinity College, Oxford, and Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Indonesia in Jakarta. His new book is on corruption in the perspective of Indonesian history (peter@projectsoutheastasia.com; www.projectsoutheastasia.com)

Special thanks to Professor Arlo Griffiths (EFEO) for the images of the Airlangga Stone in Kolkata.