Keeping religion alive: performing Pamiri identity in Central Asia

<p>The inhabitants of the river valleys of the Pamir Mountains in Tajik Badakhshan cherish a rich and multilingual tradition of oral poetry, sung on a variety of festive occasions and commemorative gatherings. For the Ismailis of Tajik Badakhshan (an autonomous region within the Central Asian republic of Tajikistan), the performance of religious poetry, called <em>maddoh</em> or <em>maddohkhoni</em>, is an important devotional practice. In Central Asia, the Ismailis form a relatively isolated Shiite minority in an overwhelmingly Sunni environment. During the civil war in Tajikistan (1992-1997), the performance of <em>maddoh</em> gained a new dimension as a powerful vehicle for expressing Badakhshani or Pamiri identity.</p>

Language, religion and identity in Tajik Badakhshan

While Central Asian Muslims are predominantly adherents of Sunni Islam, a community of Ismaili Shiite Muslims live in the Pamir Mountains, in the area of Badakhshan, situated on both sides of the Oxus River Valley in present day Tajikistan and Afghanistan. The Central Asian Ismailis, who refer to themselves as Pamiri or Badakhshani, belong to the Nizari branch of Ismailism, and thus are followers of the Agha Khan, the 49th Nizari Imam. In Tajik Badakhshan, Ismailism plays an important role in uniting the population of this area, who speak a variety of different languages, amongst which languages of the Eastern Iranian Pamir language group stand out. The languages of the Shughni-Rushani group, alongside Wakhi, are the most widely spoken Pamir languages of this area.1 Persian in its Tajik form (Tajik Persian) is the first language of some of the Badakhshanis, and a second language for most of them, as it is the official language of Tajikistan, the language of education and the lingua franca of old. Russian too is widely known, as part of Soviet heritage and as a result of the present economic situation, which has led to a steady increase of Badakhshani migrant workers in Russia today. Religion and, to some extent, language function as important identity markers that set apart the Badakhshanis from the other inhabitants of Tajikistan, who are Sunnis.

Conversion narrative: the position of Nosiri Khusraw

The Ismaili community of Badakhshan believe that they were converted from fire-worshipping to Ismailism in the 11th century AD by the famous poet and philosopher and champion of Ismailis, Nosiri Khusraw (Nāṣir-i Khusraw), and that they have always inhabited this region. Nosiri Khusraw hailed from Qubodiyon, a village in Khatlon, an area neighbouring Badakhshan. After visiting the Ismaili Fatimid caliph in Cairo, he returned to his homeland as a missionary. Nosiri Khusraw is therefore the pir, or religious guide, of the Badakhshanis, and today he is highly revered. Many poems contain references to Nosiri Khusraw, and many places are dedicated to his memory. Trees and springs which are said to have been visited by him, are now holy places where people come to find a blessing.2

Echoes of a history of persecution

Being a Shiite minority, the position of Ismailis has been a difficult one for many centuries. They were considered, within as well as outside Central Asia, as heretics, and treated as such. Though the history of the Ismailis in present-day Central Asia is to a large extent obscure, it is well possible that the Ismailis of Badakhshan live in this area because of the persecution they suffered by zealous Sunnis in the past. They found a place of refuge in the inaccessible Pamir mountains where they lived a harsh, isolated but relatively safe life, until colonial rule gradually opened up the area from the beginning of 19th century onwards and brought an end to the relative isolation of the Badakhshanis. During the Soviet period, matters of religion were temporarily pushed into obscurity, though regionalism (mahalchigi), in which religion also plays a role, remained an omnipresent socio-political phenomenon: one’s regional background mattered in both Soviet and post-Soviet Tajikistan. Immediately after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, not only regional background but also religious identity manifested themselves as major issues, demonstrated by the outbreak of civil war and its subsequent development. The lingering prejudice against the so-called heretic Badakhshanis proved to be very much alive in post-Soviet Tajikistan, and they fell victim to violence and deadly persecutions in the capital Dushanbe in 1992 and 1993, under the pretext of politics. To many Badakhshanis, these persecutions were no less than a genocide attempt. Since then, the Badakhshanis have emphasized their own religious and ethnic identity more strongly than before. One of the means to confirm this identity became a renewed interest in Ismaili religion, visible in the revival of the performance of religious poetry, a revival that had already begun in the years before, when the new Soviet policy of glasnost had facilitated the expression of religion.

Maddohkhoni as religious education and devotional practice

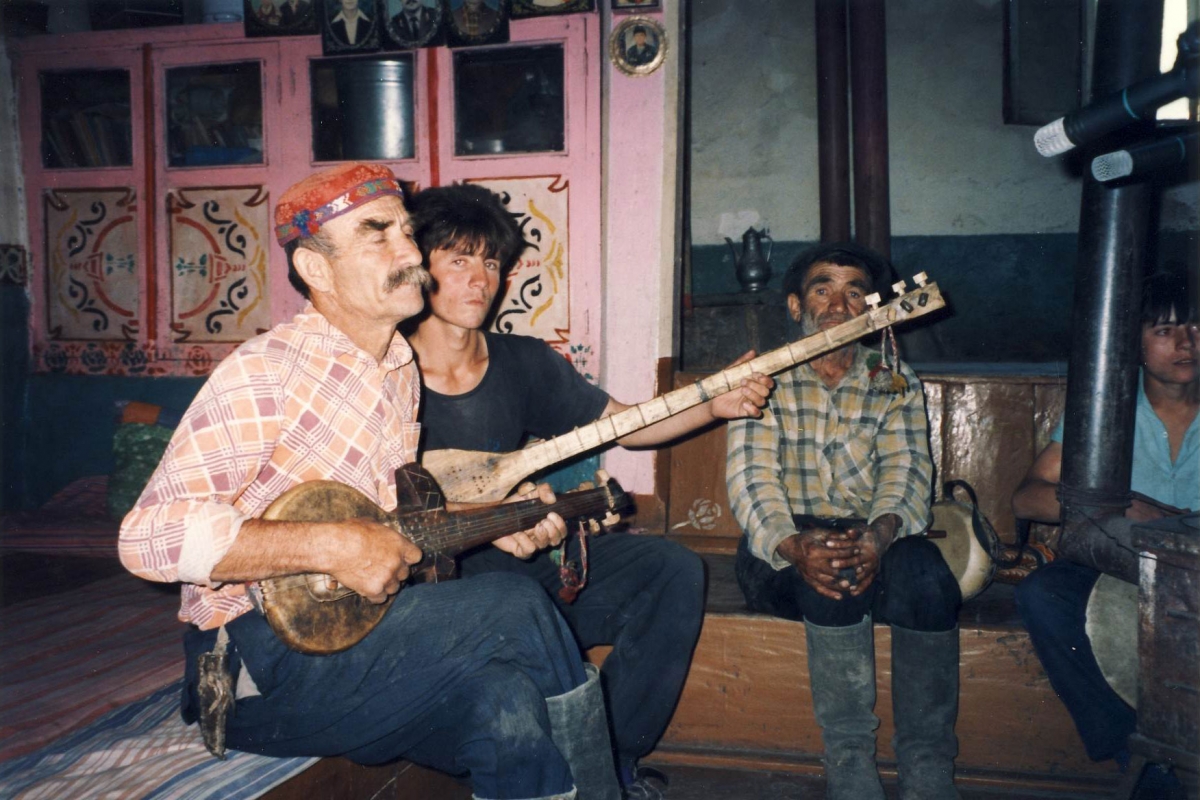

The tradition of performing religious poetry, maddoh (maddāḥ) or maddohkhoni (maddāḥkhāni), is both a devotional practice and a form of religious education. Maddoh literally means praise; in maddohkhoni, ‘the singing of maddoh’, Ismaili teachings are presented in a poetical form, sometimes in specific terms, but often in more generic terms, by way of recommendations to lead a cautious and pious life. In a performance of maddoh, long cycles of (Tajik) Persian poems are sung, generally by one to three male musicians who accompany themselves by a fixed set of musical instruments, among which the rubobi pomiri or Pamiri lute is prominent. Many of these poems can be described as mystical; a fair number of them are ascribed to the great Sufi poet Rumi (1207-1273). Other poems praise the heroic deeds of the central figures of Badakhshani Ismailism. It is noteworthy that Tajik Persian is not the mother language of the majority of Badakhshanis, and that Persian in this specific tradition functions as a liturgical language.3

A tradition outside the scope of ‘nationalisation’ in a Soviet framework

During the Soviet period, many genres of music found new functions and contexts: taken out of their original, often ritual context, music was now also performed on stage in state theatres by large ensembles of professional musicians, who were trained in state institutions. These genres thus became part of a newly formed national music tradition, which in turn influenced and adapted the perspective people had of this music. Though Badakhshani music with a more secular character was also part of this process, as an obvious religious genre, maddohkhoni remained entirely outside of this ‘theatrification’.4 Musicians who performed on stage in public were in some cases also maddohkhons, ‘singers of maddoh’ in private, but in many cases maddohkhons were non-professional musicians who performed maddoh in the seclusion of the village community in the framework of religious commemoration, as a communal service; specifically, but not exclusively, as a mourning ritual. Maddohkhons are by definition non-professionals in the sense that they do not make a living out of maddohkhoni; even if they are professional musicians otherwise. During the civil war, under the harsh circumstances of repression and isolation, maddohkhoni gained new prominence amongst younger Badakhshanis and amongst musicians who previously were not involved in maddohkhoni. Most maddohkhons learned the canon of music and poetry connected to the tradition of maddohkhoni in their own village or town, from their father or grandfather or a neighbour, and on the basis of a bayoz (az ruyi bayoz) or notebook, indicating poetical anthologies, sometimes in Arabo-Persian script, sometimes in Tajik-Cyrilic script, kept safe in the family circle. Since the profession of Ismaili faith is now less restricted, especially since the Agha Khan came to meet his followers in Tajik Badakhshan for the first time in 1995, maddohkhoni has acquired a new public dimension, with stage performances and primarily local television broadcasts.

Occasions for performing maddoh

The performance of maddoh remains to be connected, however, to certain, fixed occasions. Maddoh can be sung all night long as part of mourning ceremonies, presided by a so-called khalifa, who contextualizes the poetry sung by the maddohkhons during this and other ceremonies. Maddoh may also be performed on Thursday evenings, on Fridays, or on request; a more specific occasion is the annual commemoration (ayyom) of a holy grave or mazor. Badakhshan has many such graves, in which saints or pirs have been buried; these graves are small stone buildings marked by horns of the ibex. They are usually situated just outside the village and are carefully maintained; they stand out as landscape markers of devotion.5

Maddohkhoni is the major form of religious commemoration for the Ismailis of Tajik Badakhshan. Though devotional practices based on music and poetry are current amongst Ismaili communities elsewhere, and indeed amongst Muslim communities at large, the context, form and development of the tradition of maddohkhoni are in many ways unique. In the recent past, when Tajikistan gained independence and plunged into civil war, maddohkhoni started to function prominently as a powerful means to express Pamiri-Ismaili identity. In present-day Tajikistan, the tradition continues to evolve under the influence of renewed ties with the global Ismaili community and new forms of patronage that come along.

Gabrielle van den Berg is University Lecturer in Cultural History of Central Asia and Iran at the Leiden Institute for Area Studies (g.r.van.den.berg@hum.leidenuniv.nl).