Journey to Dunhuang: Buddhist art of the Silk Road caves

<p>During World War II, James C. M. Lo 羅寄梅 (1902–1987), a photojournalist for the Central News Agency, and his wife Lucy 劉氏·羅先 arrived at Dunhuang. James Lo had taken a year’s leave to photograph the Buddhist cave temples at Mogao and at nearby Yulin. Lucy was also a photographer, and together they made the arduous journey in 1943. They systematically produced over 2500 black and white photographs that record the caves as they were in the mid-20th century.</p>

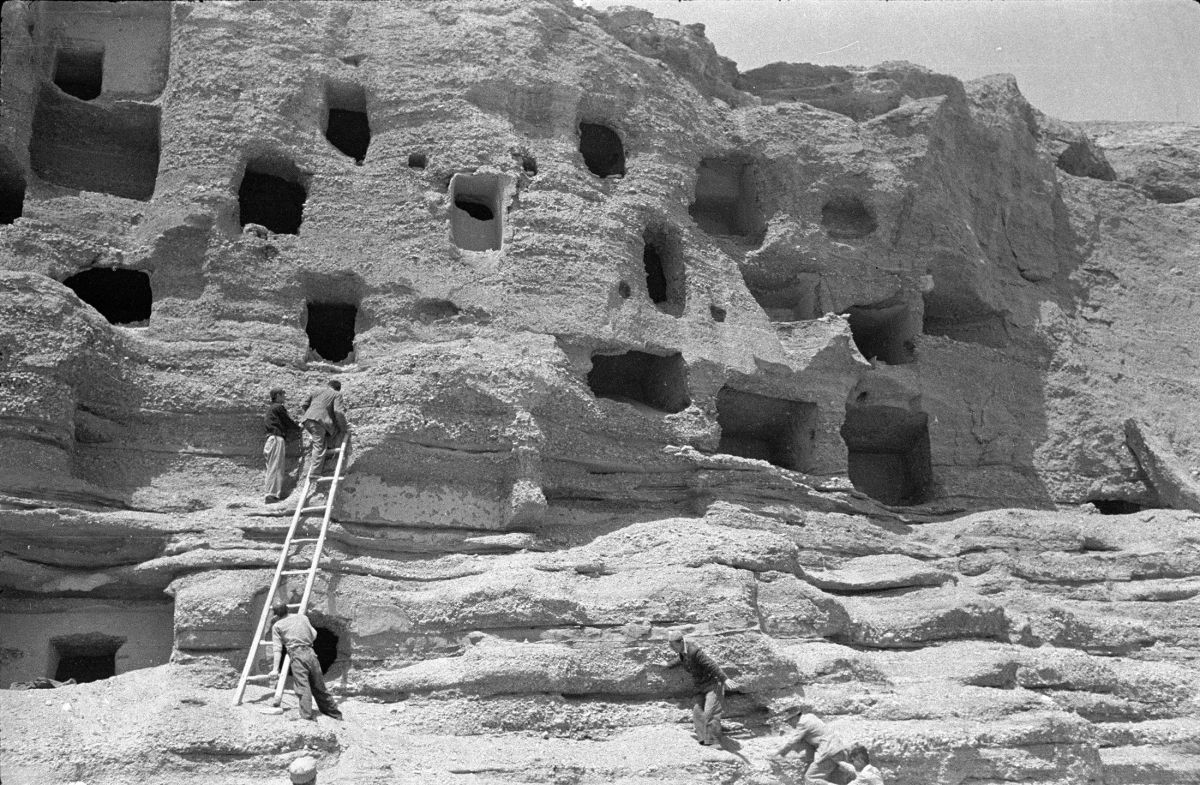

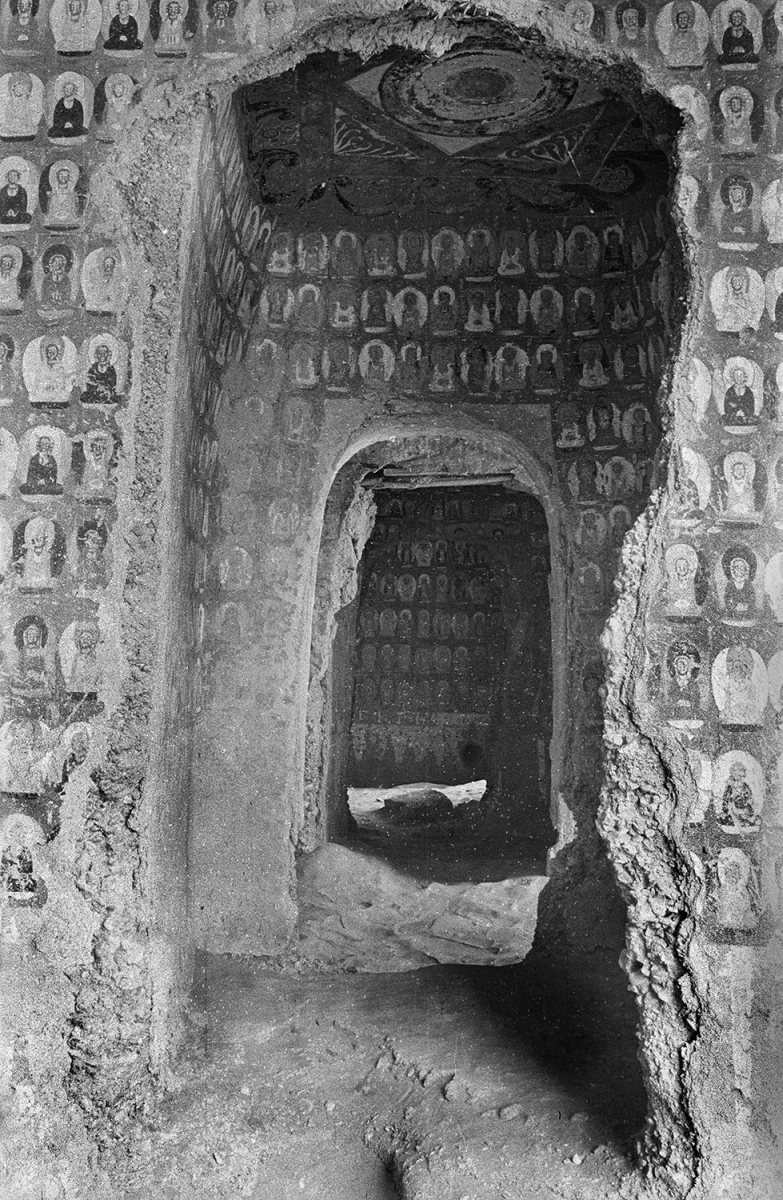

The Lo Photographic Archive is a feat of ingenuity, organization, and sheer courage. Over the course of 18 months, the Los worked without electricity or running water. By day the couple used a system of small mirrors and cloths to reflect adequate light into the caves. By night they developed negatives with water from a nearby stream. Their photographs are historically very valuable since many of the views recorded no longer exist today. They are also of unusual artistic importance and reflect the Los’ remarkable aesthetic sensibilities (fig.1 & 2).

This exhibition brings us the visual splendors of Dunhuang’s cave temples through the eyes of James and Lucy Lo, with a selection of their photographs, their collection of Dunhuang manuscripts, and life-size reproductions of the Mogao murals painted a decade later by young artists whom the Los inspired in Taiwan. While color publications and 3D digital models record Dunhuang with current technological sophistication, we are reminded of how the unwavering commitment of two people adds immeasurably to our deeper understanding of Dunhuang.

Manuscripts and Zhang Daqian

The ancient documents that James and Lucy Lo collected while at Dunhuang reflect the Los’ broad interests in unusual scripts and their appreciation of various painting techniques.1 Some are a direct result of their meeting famed Chinese painter – and infamous forger – Zhang Daqian 張大千 (1899-1983), who was at Dunhuang repairing and making replicas of Mogao murals. He helped the Los form their collection of manuscript fragments and a few carry both their seals. For Zhang, Dunhuang represented a pure Chinese past and was key to reenergizing the Guocui 國粹 or ‘National Essence’ group.2 Zhang’s copies of the Mogao murals were exhibited on a world tour in Paris and at other venues. He even mined Dunhuang imagery to create a master forgery that he sold to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as an ancient work.

Multicultural Dunhuang

Located at the convergence of the northern and southern routes of the Silk Road, Dunhuang was a multicultural desert oasis. Many languages were spoken there, including Chinese, Tibetan, Uyghur, Tangut and Hebrew. Several multilingual texts in the Lo collection attest to this diversity. They include two Yuan-dynasty sutras on display: written in Old Uyghur (Old Turkic) language and script, interspersed with Chinese; and printed in Tangut, a near extinct Sino-Tibetan language of northwestern China’s Xi Xia dynasty (1038–1227). Impressed on the latter is the Chinese seal of monk Guanzhuba 管主巴 (Tibetan: bKa’ ‘gyur pa, active 1302), an official of either Tangut or Tibetan descent who oversaw the printing of Buddhist texts in Chinese, Tangut, and Tibetan scripts.

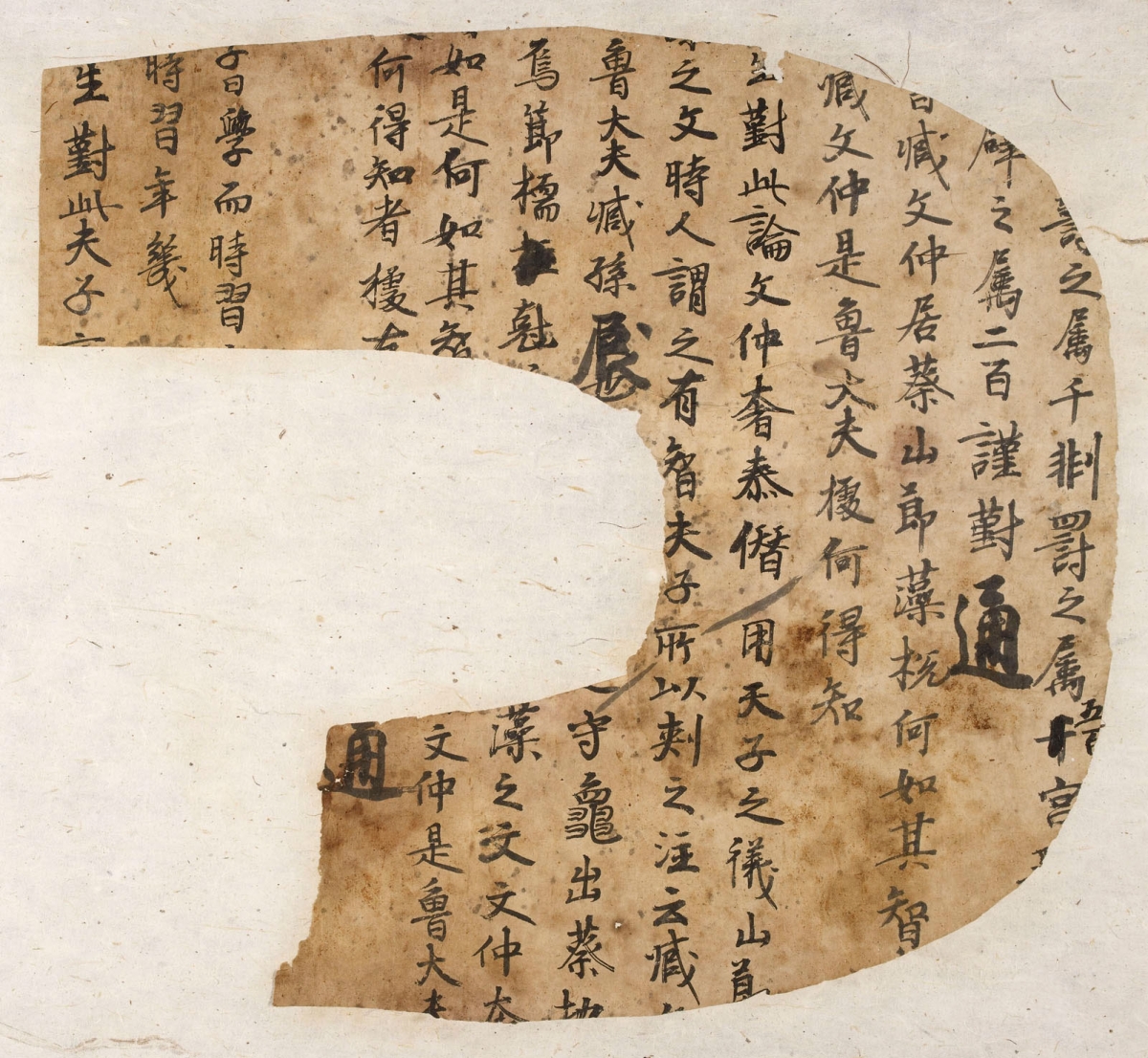

Two manuscripts in the exhibition demonstrate a connection between Dunhuang and Chang’an, the capital of China in the Tang. They are test papers on the Confucian classics, likely from a local school in Dunhuang or Turfan. They represent aspirations to sit for the official examinations: the military conquests of Emperor Taizong 唐太宗 (r. 626–649) made it possible after the mid-7th century for the cultural values of central China to be transmitted to the western frontier through Confucian education. Since paper was precious, the manuscripts were later recut into a distinctive U-shape to form the upper part of a burial shoe (fig. 3).

Artist renditions and recording damage, old and new

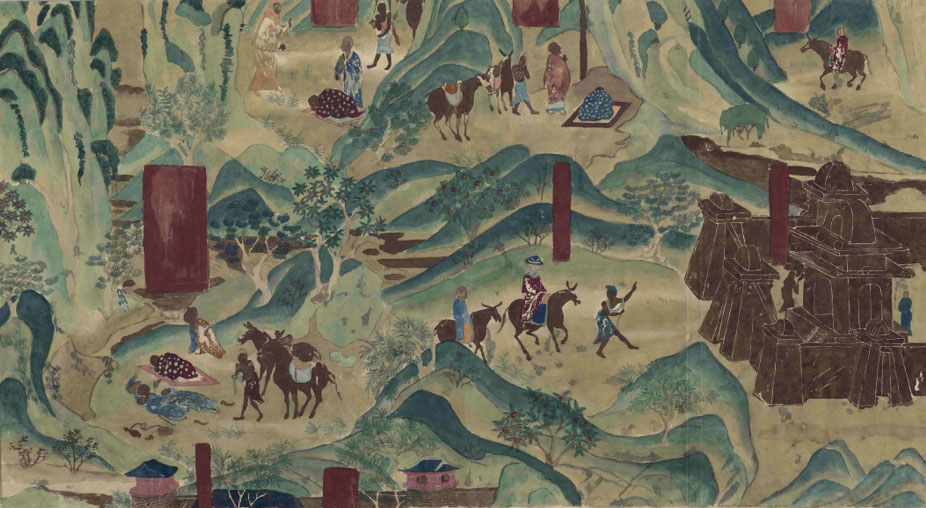

After moving to Taiwan in the 1950s, the Los became part of a community of artists and scholars. They invited a group of young artists to produce life-size copies of the Dunhuang murals, based on the Los’ slides and Lucy’s meticulous notes (fig. 4). Some were displayed at the 1964-65 World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows in Queens, New York, at the China pavilion. These facsimiles are indeed comparable to Zhang Daqian’s celebrated copies, and similar in their impulse to perpetuate knowledge of the ancient past through acts of reproduction.

By the end of the Tang dynasty, the cliff face at Mogao was completely covered with caves. Since no new caves could be opened, donors paid for existing ones to be redecorated and their portraits would sometimes be added to the cave walls. Some Lo photographs document how walls were deeply scored during renovations, in preparation for a new, smooth surface of white gaolin clay; to James these scorings formed patterns of intrinsic visual interest. Using his black-and-white photographs of one such destroyed mural in Cave 13 – of its donor, the Lady Wang – an artist recreated a full color portrait by supplying details like her hair accessories and diaphanous shawl. Two huge artist renditions from the Lo ‘workshop’ depict the processions of Cave 156’s donors, General Zhang Yichao and his wife. These images record disfigurements from the relatively recent effects of over 900 White Russians living in the Mogao caves in the 1920s after fleeing Russia’s civil war. They left graffiti, and their cooking fires charred walls and blackened statues.

The Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection

This exhibition also presents an opportunity to view objects from the SAM’s collection. One is an impressed-clay votive tablet depicting a Buddha with pendant feet. The twelve-character inscription establishes a Tang dynasty date, around the 7th to 8th century, given the calligraphy’s proximity to the style of Tang courtier Chu Suiliang 褚遂良 (596–658). The previous owner, Ye Changchi 葉昌熾 (1849–1917), late Qing scholar and bibliophile, claimed that it originated from Dunhuang. And on display for the very first time are two wall painting fragments from the Kizil caves in Xinjiang province that were amongst many artifacts brought to Germany by explorers Albert Grünwedel (1856–1935) and Albert von Le Coq (1860–1930) from their Silk Road expeditions around 1905 to 1914.

FOONG Ping, Foster Foundation Curator of Chinese Art, Seattle Art Museum and Affiliate Associate Professor, University of Washington (PFoong@SeattleArtMuseum.org)