Japanese Wives in North Korea

Japanese women who migrated to North Korea (DPR Korea) with their Korean husbands during the exodus of Zainichi Koreans from Japan are known as ‘Japanese wives’.[1] They are now quite aged, around seventy to eighty years old, and wish to travel to their motherland Japan, in order to meet brothers, sisters and other relatives, or to visit the graves of their ancestors before they die themselves. The existence of these Japanese wives in North Korea is not well known, but their experiences as ‘the Other’ in North Korea is a greatly interesting topic.

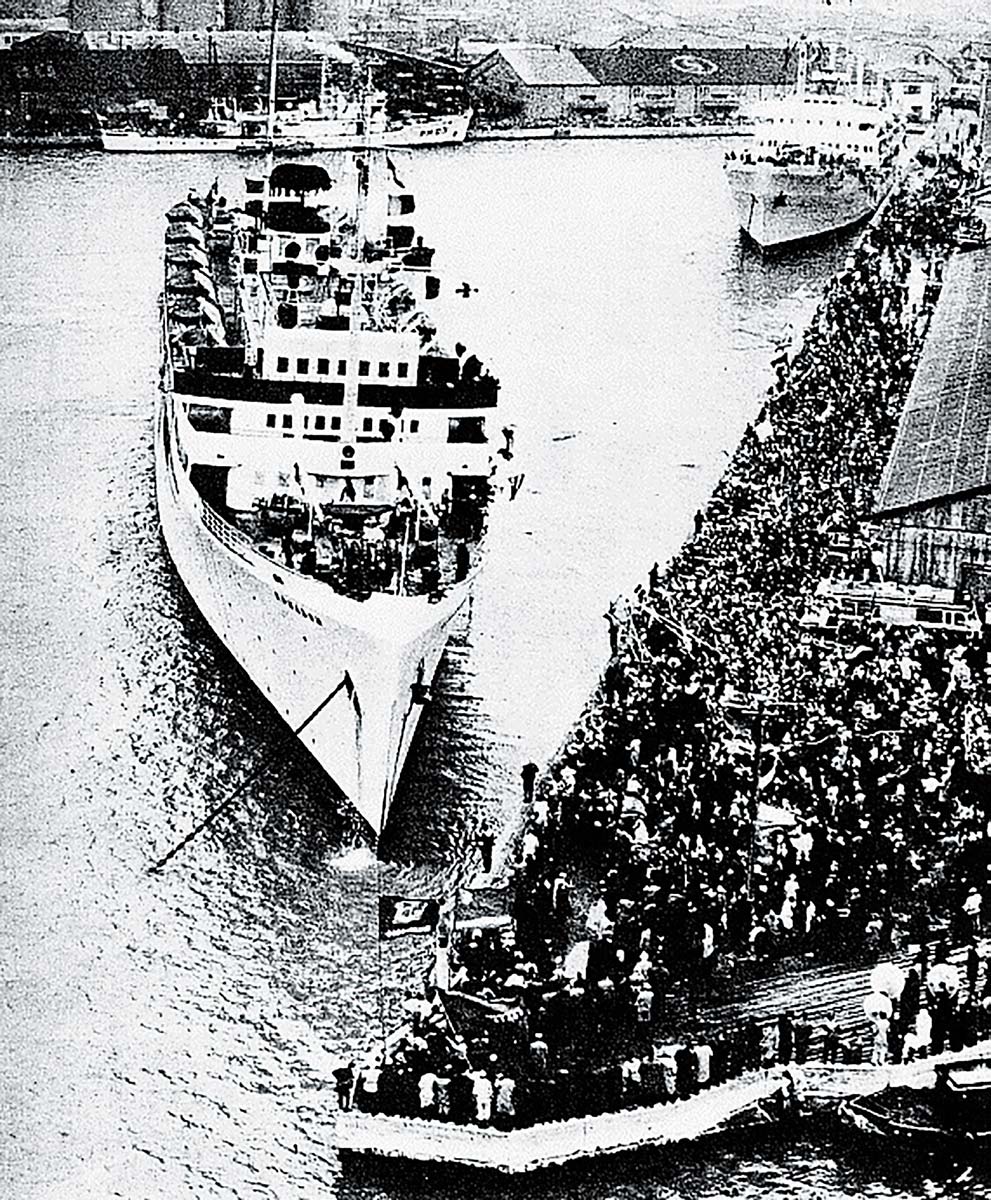

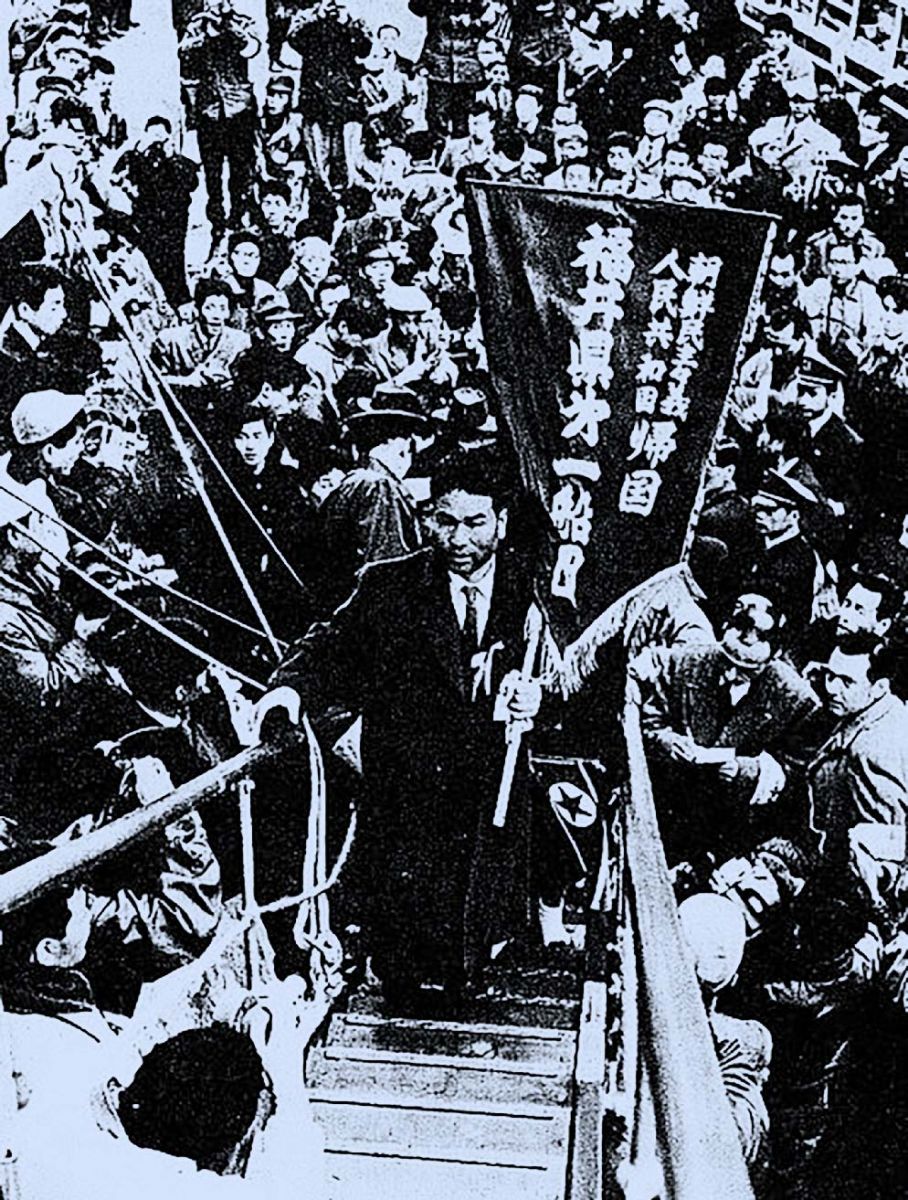

Zainichi Koreans are those who came to Japan during Korea’s period of Japanese occupation as a result of forced labor, or reluctantly in order to earn a living. Also included in the category of Zainichi Koreans are their descendants. The majority of Zainichi Koreans suffered discrimination by the Japanese people and faced hardships due to unemployment and poverty. The exodus of Zainichi Koreans from Japan to North Korea began in 1959; by 1984, about 93,339 people had moved to North Korea. Included in this number are at least 6,679 Japanese nationals, some of whom were women, who had Zainichi Korean spouses. The number of women – the so-called Japanese wives – was 1871. Such a large-scale movement of people from a capitalist country (Japan) to a socialist country (North Korea) in the Cold War Period was a very rare case indeed.

The exodus of the Zainichi Koreans began when the North Korean leader Kim Il-sung declared that North Korea would welcome the Zainichi Koreans in North Korea. The North Korean government may have intended to improve the country’s image within international society by accepting the Zainichi Koreans. However, the Japanese government and the Red Cross Society of Japan had their own reasons for wanting this group of people to move.[2] Japanese society at the time was going through a period of post-war restoration; the policy towards the Zainichi Koreans was a great worry, liability, and burden to the Japanese government. One solution for this ‘problem’ was to make Zainichi Koreans move to North Korea.

Many, but not all, of the Zainichi Koreans were actually from the southern regions of the Korean Peninsula, but the decision to immigrate to North Korea was based on political grounds or in the hope of a better future; they were determined to ‘return’ to a country that they had never been to before. For these Zainichi Koreans, North Korea was their motherland and South Korea merely their hometown. Of the Zainichi Koreans who moved to North Korea, some were accompanied by their Japanese spouses, and the majority of these cases consisted of a Korean husband and a Japanese wife. These Japanese wives saw North Korean people for the first time when their ship, which had departed from Niigata port in Japan, arrived at Chongjin port in North Korea; most were shocked to see the North Korean people who had come to the port to welcome them because they looked poor.

The Japanese wives and their families settled down in the areas designated by the North Korea government and living standards differed from person to person. Some lived in urban environments, such as the capital Pyongyang or other regional cities, whereas other families were provided with houses in the countryside. Those who lived in the countryside faced significant hardships. Some of the Japanese wives passed away early on already as they could not adapt to the food scarcity and the social environment of North Korea. Of course, there were also those who enjoyed a happy life, to some extent, with their families. Although the situations of the Japanese wives may have differed among people, they shared a common desire – to visit their hometowns in Japan.

The hometown visits of these Japanese wives were carried out on three occasions – November 1997, January 1998, September 2000 – but they have not taken place since then, due to political problems between Japan and North Korea. In May 2012, Kyodo News (a Japanese wire service) reported on Ms. Mitsuko Minagawa in Pyongyang, a Japanese wife. The reporter asked Ms. Minagawa, “Do you hope to go to Japan?” and her answer was “Of course I hope, because my hometown is there. I hope I can travel back and forth between North Korea and Japan. For that I hope both countries will normalize diplomatic relations as soon as possible.” In recent years, there have been some Japanese journalists who have energetically reported on the issue of these Japanese wives, for example Takashi Ito and Noriko Hayashi. Takashi Ito has reported on the existence of a ‘circle’ of Japanese wives – the ‘Hamhung Rainbow Association’ – based in Hamhung, the largest city on the east coast of North Korea. The circle provides a mutual exchange and fellowship between Japanese wives. In the absence of diplomatic relations between Japan and North Korea, it is difficult to travel freely between Japan and North Korea. The short trip made by Japanese wives in September 2000 was the last to take place. In order for such trips to take place, special humanitarian measures must be taken through the Red Cross Society of Japan and North Korea. However, such procedures are heavily influenced by international relations between Japan and North Korea and so the possibility of such measures being realized are, at present, uncertain.

The Japanese wives issue was dealt with in Japan-North Korea diplomatic negotiations. On 17 September 2002, the 'Japan-North Korea Pyongyang Declaration’ marked a turning point in relations between Japan and North Korea. The Japanese wives issue was also addressed in the ‘Japan–North Korea Stockholm Agreement’ of May 2014. The subsequent deterioration of Japan-North Korea relations, however, has meant that additional trips by Japanese wives have yet to take place. The Japanese government has set the resolution of the ‘North Korean abductions of Japanese citizens’ as a top priority in negotiations with North Korea, and comparatively the issue of the Japanese wives is of a lower priority. However, the Japanese wives are already quite old and time is running out. For them, this is an issue that must be dealt with as soon as possible.

Tomoomi Mori, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Letters, Otani University tt-mori@res.otani.ac.jp

[1] These ‘Japanese wives’ should be distinguished from other female ‘Japanese residents of the Korean Peninsula’ who continued to live in North Korea even after the defeat of Japan in 1945 as they were not able to return to Japan due to certain circumstances. The concept of ‘Japanese residents of the Korean Peninsula’ first appeared on 7 April 2018, on TV Asahi’s 2018 TV documentary ‘Family ties connecting Japan and North Korea’, reported by Takashi Ito.

[2] Morris-Suzuki, T. 2007. Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan's Cold War. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.