The introduction of revolutionary 'new books' and Vietnamese intellectuals in the early 20th century

<p align=\"left\">The First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) widened the Chinese intellectuals’ vision. They realized China’s weakness in the face of Japanese military intrusions and felt the need to transform their country into a prosperous ‘modern’ nation. Chinese reformers began to develop journalism and translate numerous European and Japanese works in order to introduce their compatriots to the various fields of Western sciences and ideas. As was the case with China, and thanks to the dissemination of ‘new books’ introducing reform ideas, intellectuals in Vietnam as well as in Korea also started to look to the outside world to help them reconsider their own lands. This paper analyses the Vietnamese case where the movement was particularly effective.</p>

As Rebecca E. Karl demonstrates, the understanding by European and Japanese scholarship of contemporary events in countries such as Poland, the Philippines, and Hawaii influenced the way Chinese thinkers thought about the future direction of their own country. 1 On that basis, between the late 19th century and the early 20th century, reform ideas were introduced from China to Vietnam and Korea through the so-called ‘new books’ (xinshu 新書 in Chinese; tân thư in Vietnamese), which were the vehicle of a ‘new learning’ (tân học in Vietnamese). The intellectual progress in respectively Vietnam and Korea was tangible and comparable. However, a difference soon appeared in the degree of distribution of ‘new learning’ in Vietnam by the revolutionary party of Sun Yatsen (孫逸仙).

How did Vietnamese reformers and Chinese revolutionaries encounter each other? Did the Chinese emigrants to Indochina play a role in developing a network of communications between the Chinese and Vietnamese activists? Was there strong interaction between these two groups? Finally, what was the political position of the Vietnamese reformers? To answer these questions one should explore the dissemination of revolutionary ‘new books’ into Vietnamese society, via a complex web of agents and a path of circulation that has one locus in Europe, and more specifically, Paris.

The complex circulation of revolutionary magazines into Vietnam

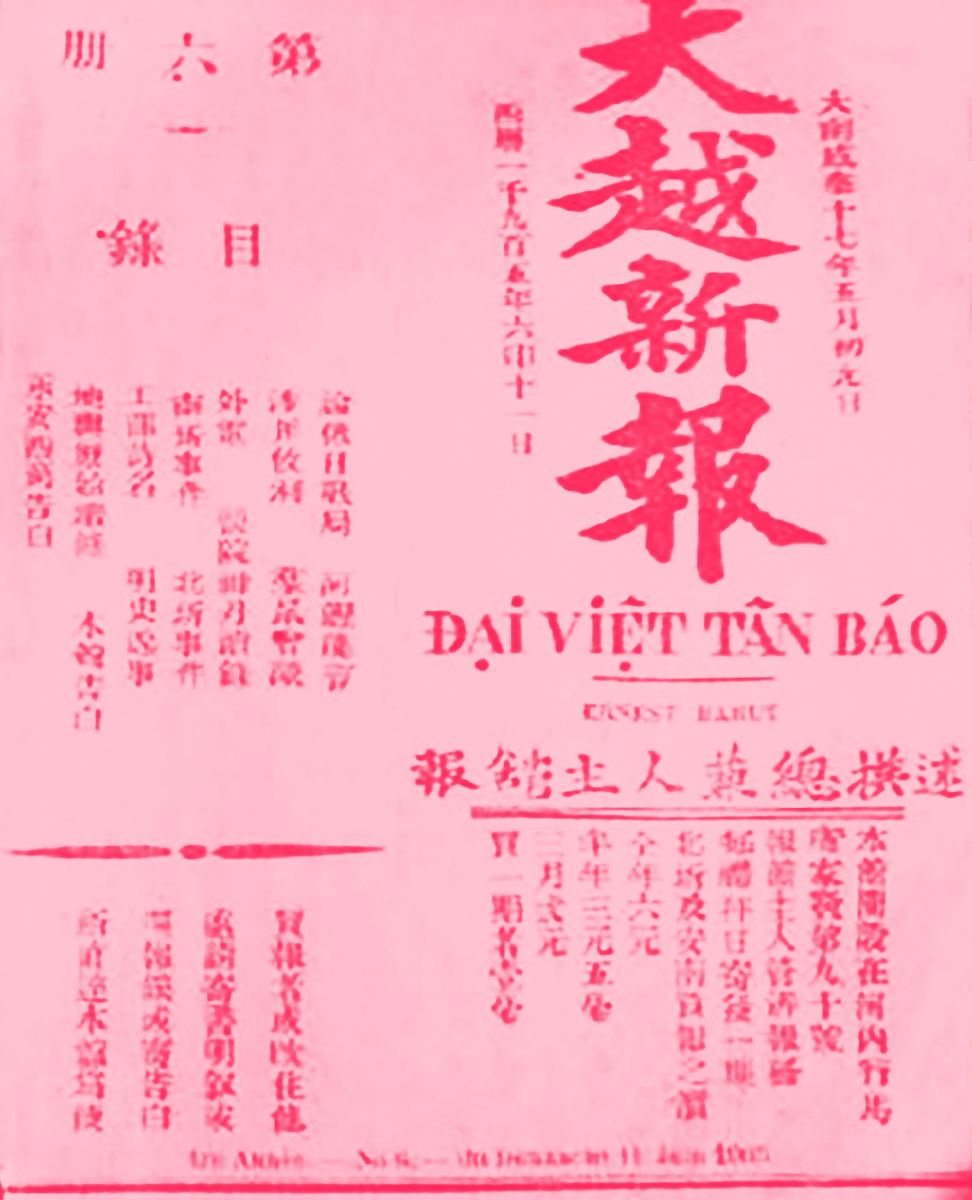

From the end of February 1903, the presence of the Chinese revolutionary Sun Yatsen in Indochina was a great matter of concern to Governor General Paul Beau because of the plots that the revolutionary could possibly foment with the numerous Chinese nationals residing in the colony. In fact, Paul Beau supposed that Sun Yatsen had a considerable influence on the secret societies that counted among their members a part of Indochina’s Chinese residents, as well as a few Annamese. 2 Jean-Louis de Lanessan, former Military Governor of French Indochina, wrote on 10 July 1908: “Today, there can be no doubt that there are communications between the Annamese rebels and Chinese reform associations.” 3 As Governor General Antony W. Klobukowski later also pointed out (1908), it is in large part from the Chinese revolutionary literature that Vietnamese intellectuals gained their reform creed and their new ideas. 4 In fact, biographies of Chinese revolutionaries as well as Chinese journals and magazines published by Sun Yatsen’s party penetrated more and more into Vietnam during the early 20th century. The magazine Xin Shiji (新世紀 La Tampoj Novaj, Le Siècle Nouveau, New Century) is a very interesting example (fig.1).

Xin Shiji was founded in Paris by a group of Chinese anarchists and revolutionaries, including Wu Zhihui (吳稚暉), Zhang Renji (張人傑), and Li Shizeng (李石曾); its first issue appeared on 22 June 1907. The newspaper printed 1500 copies, which were not sold in Paris, but were shipped directly to China. Bundles of Xin Shiji, which were distributed clandestinely in the French colony as well as in the Chinese empire, also found their way into many Vietnamese villages. 5 Issue n° 101 (12 June 1909) indicates that it was distributed free of charge to subscribers in the city of Hà Nội. Xin Shiji was published weekly until its final issue, n° 164, at the end of June 1910. Xin Shiji advocated the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty by an insurrectional movement, and was thus considered to be a revolutionary magazine and an anti-Manchu and anarchist journal by the Chinese government, who ordered post offices at all Chinese entry ports to confiscate Xin Shiji as soon as it was shipped into the country. In addition to regular papers and essays, the magazine also featured the written correspondence between a Chinese person in Indochina and a newspaper in Formosa; the correspondence implied the desire of the Vietnamese people, particularly the Tonkinese, to expel the French from their colonized territory. According to the Chinese local correspondent, these independence projects were maintained by the introduction into Vietnam of revolutionary works, many of which the Governor General of Indochina had already seized. The Chinese emigrants in France and Vietnam, in particular the Chinese communities originating from the city-port Swatow, 6 played a crucial role. The revolutionary propaganda and the exaltation of political assassination could definitely have had an impact on the spirit of the Vietnamese people.

In Vietnam, the reform ideas and movements of the early 20th century were divided into two trends: the supporters of pacific reform and the supporters of uprising and revolution. It is under the influence of radical ideas that the latter proposed to resort to external assistance and foment insurrection in order to recover national independence. And so a revolutionary movement was hatched, just as designed by the ‘new books’ originating from the party of Sun Yatsen. Little by little, a group of Vietnamese reformers turned to the Chinese revolutionary party that seemed capable of carrying out the task of reorganizing Vietnam.

Encounters between Vietnamese reformers and Chinese revolutionaries

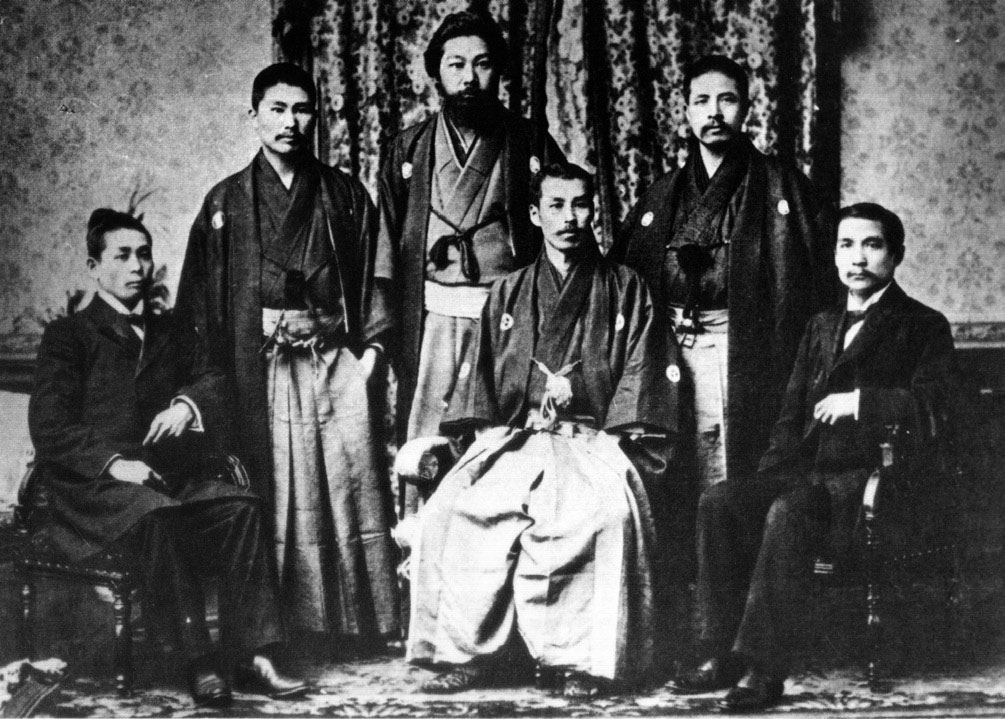

While Korean reformers had little direct links with Chinese revolutionaries in the early 20th century, Vietnamese reformers were actively making contact with them. The case of the famous Vietnamese revolutionary leader Phan Bội Châu, the founder of the Đông Du (Journey to the East) political movement, is significant. Leaving Vietnam on his way to Japan at the beginning of 1905, Phan contacted Feng Ziyou (馮自由), one of Sun Yatsen’s confidents, in Hong Kong. After his arrival in Japan, Phan did meet the Chinese revolutionary leader, who had returned from the United States and was residing in Yokohama. Phan Bội Châu also had numerous contacts with other Chinese comrades. He had also been able to read the revolutionary ‘new books’ translated into Chinese such as Contrat Social (The Social Contract) by Rousseau and L’Esprit des Lois (The Spirit of the Laws) by Montesquieu; in his autobiography, Phan Bội Châu swore that he had already disposed of the monarchical doctrines in his mind. 7 In this regard, the concerns of the Chinese and French authorities were well-grounded: the influence of Chinese emigrants in Vietnam on their local ‘comrades’, and the subsequent repercussions of the Chinese revolutionary movement in Indochina, could develop into the real possibility of a conspiracy formed by ‘agitators of the two countries’ (i.e., China and Vietnam).

Having entered into relations with young Chinese reformers in Japan in 1905, Phan Bội Châu established contacts with Chinese students in Yunnan and Guangxi, and subsequently formed a Yunnan-Guangxi-Vietnam League in the summer of 1907. These exchanges were maintained thereafter in Vietnam. There was at least a branch of this league in Hà Nội, called the ‘League of Two Nam’ (Việt Nam and Vân Nam = Yunnan). In addition, during a secret visit to his country at the beginning of 1907, 8 Phan actively supported direct contact between Chinese and Vietnamese activists. Phan’s political action and propaganda was expanded with the help of the Yunnanese revolutionary group in Indochina; these Chinese emigrants played an important role in encouraging meetings intended for possible cooperation among revolutionaries. 9

Moreover, like the Chinese revolutionaries, Vietnamese patriots began to take advantage of the unrest in the two countries. Phạm Quỳnh (1892-1945), a monarchist who served as a government minister under Emperor Bảo Đại's administration, wrote in a note about Phan Chu Trinh: 10 “In reality, the Vietnamese reformers secretly nurtured a hope of fomenting a revolution against the protectorate with Chinese assistance. The attempts of 1908 and the following years were the consequence of all these movements.”11

From tax resistance to uprising

As one of the concrete outcomes of revolutionary agitation that ultimately led to the 1911 Xinhai Revolution in China, it is very interesting to compare the origin and development of the respective tax resistance movements in China and Vietnam. Indeed, the most important cause of unrest in China as well as in Vietnam resided in the weight of the taxes. In the early 20th century, the increase of taxes and the creation of new taxes in China caused a general discontent among the population of Guangdong (廣東), where serious disorders erupted in several locations between April and July 1907. 12 Immediately after those events in South China, a tax resistance movement occurred in Central Vietnam, where the taxes had been increased with more speed. On 6 February 1908, the decision imposed on the residents of the Province of Quảng Nam to immediately provide the newly required corvée labor ignited violent opposition. On 12 March 1908, a few hundred inhabitants of the sub-prefecture Đại Lộc gathered in front of the local governor’s residence to demand the reduction of taxes. Other demonstrations ensued between April and May in Quảng Nam as well as other provinces and cities: Quảng Ngãi, Thừa Thiên, Phú Yên, Nha Trang, and Phan Thiết. 13

While it is hard to track the actual connections between China and Vietnam regarding tax resistance, beyond parallel dynamics and similar chronology, the April 1908 Hekou (河口) uprising in Yunnan shows that a conspiracy had been jointly prepared by unknown Chinese and Vietnamese revolutionary activists. In the night of 29 April, the market of Hekou, located on the Sino-Vietnamese border opposite the border town Lào Cai, was attacked by a group of Chinese revolutionary partisans. It is very likely that secret agreements had been reached between the Chinese rebels and the Vietnamese soldiers of the garrison stationed in Indochina. The Vietnamese gunners participated in this military operation: the French military Robert, responsible for the outpost, heard “the bullets whistle above his head”. 14 Moreover, after the failure of four Sino-Vietnamese border uprisings between 1907 and 1908, most of the Chinese revolutionaries had returned to Tonkin, in particular to Hà Nội. From then on, the revolutionary campaign moved from the border to the inland area, and took on new forms.

On 27 June 1908, the first part of the insurrection plot was carried out. At dinner, two French infantry companies of the Hà Nội garrison were poisoned – and barely survived. It is an established fact that Chinese revolutionaries were involved in this conspiracy of Vietnamese activists planning to poison the French troops. The attempted poisoning was executed by the employees who were working in the barracks and the plan was to remove arms and ammunitions from the colonial forces. Immediately after the French authorities discovered this criminal plot, a curfew was enforced and a large number of suspects were captured. Because of the involvement of several Chinese revolutionary refugees in this conspiracy, approximately one thousand of them were thrown in jail. 15

At the time, the French authorities began to suspect that Lương Văn Can, one of the founders of Ðông Kinh Nghĩa Thục (the Tonkin Free School 16 ), was a member of ‘secret societies’, and that he was also maintaining relations with several persons who had taken part in this poisoning conspiracy. Later, his ongoing relations with Ernest Babut, former French director of Ðại Việt Tân Báo (Ðại Việt Times), were equally significant. Ernest Babut, a socialist activist in the Human Rights League, critical of colonial rule and considered an agitator, was not only the defender of the Vietnamese reformers, but also of the Chinese revolutionaries. On 10 November 1909, Babut had a meeting with Lương Văn Can about financial issues. Before parting with Lương after the meeting, Babut showed him the portrait of Sun Yatsen and told him: “He is one of my good friends. A lot of Vietnamese ought to be like him.” 17 , ‘Fonds du Gouvernement Général de l’Indochine’ (Documents of the General Government of Indochina), f.4.151.]

Compared to Korea, the introduction of revolutionary ‘new books’ into Vietnam benefited from several specific factors: the relatively stable presence of Chinese emigrants in Vietnamese society, the extension of the influence of Sun Yatsen into Indochina and the dissemination of revolutionary ideas and movements. In particular, the uprisings that shook South China in the early years of the 1900s had their inevitable impact on Vietnam. Unlike in Korea, where the resistance against the Japanese was not fueled from outside ideas and groups, the territory of Indochina thus served as the basis for the establishment of a furnace of revolutionary propaganda against the colonial government.

Youn Dae-yeong, Institute for East Asian Studies, Sogang University, Seoul (vinhsinh98@hotmail.com).

![The first issue of Xin Shiji (新世紀/Le Siècle Nouveau/New Century). Source: AMAE (Archives du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères/Archives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs), NS (Nouvelle Série/New Collection), vol.695, file: ‘Affaires contentieuses. Pièces et affaires diverses’ [Contentious cases. Various documents and cases]. The first issue of Xin Shiji (新世紀/Le Siècle Nouveau/New Century). Source: AMAE (Archives du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères/Archives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs), NS (Nouvelle Série/New Collection), vol.695, file: ‘Affaires contentieuses. Pièces et affaires diverses’ [Contentious cases. Various documents and cases].](/sites/default/files/38-39_IIAS_79_Page_1_Image_0001.jpg)