Interpreting the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games

Few events bring the world together like the Olympic Games. With preparations for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics in full swing, Japan is also bracing for another kind of competition: securing interpreters for the games. Ever since its election, Japan has been taking advantage of its role as host of the most prestigious global sporting event to reshape its multilingual dialogue and international communication industry, in order to provide increased access to language services and facilitate interactions between Japanese and foreign sportspeople, dignitaries, officials, and tourists.

The Olympics: a matter of international communication

The Olympic Games are considered to be the foremost international sports competition, with more than 200 nations participating. For the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympic Games, an estimated 20 million overseas tourists will visit Japan and thousands will attend Olympic events, with an already confirmed US$ 3 billion in domestic sponsorship revenue, 3.5 million tickets already sold, and an expected total additional revenue of US$ 5.6 billion.1 To maximise opportunities of economic growth and internationalisation, Japan is preparing to provide the best visitor experience to guests from all over the world, including specialist sports and general assistance interpretation services, ensuring that everyone can communicate and enjoy their visit, no matter the languages they speak. According to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics organising committee,2 more than 35,000 volunteers and professional interpreters will be onsite to offer language assistance, and the Nara Institute of Science and Technology researchers are working on a lag-free interpretation system and app to instantaneously translate the games’ Japanese commentary into 27 languages. Whether performed entirely by humans or mediated by AI technologies, interpreting will play a major role in a variety of Olympic settings, with interpreters drilling their skills to connect visitors and residents and save them from the potential chaos of language barriers.

Interpreting the past and the future of the Tokyo Olympics

The practice theory turn in social research has produced abundant studies of the world as being populated by ‘practices’: routine actions and behaviours that are meaningful to people in their localities and composed of different elements, such as bodily and mental activities, material artefacts, knowledge, emotions, skills, and so on.3 There is a wide set of scholarly literature on the dynamics and economic histories of organisations, work, and markets as practices in the Western World, but there is hardly any study on labour practices in the Japanese context, that is, on the ways in which work can be investigated as an interconnected flux of experiences, competence, materiality, and emotionality. My work aims at partially filling this gap and investigates the language industry in Japan, with a focus on the profession of interpreting, exploring dynamics, performances, and organisations of mediated communication services in terms of expertise and market relations.

When I conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Tokyo, I had just developed a socio-historical perspective on the genealogical orientation of the language industry in Japan,4 as I was particularly interested in how the professional practice of interpreting emerged, was perpetuated, and changed in the context of the neoliberal Japanese labour market and in view of recessions. Now an integral part of international society and economy, interpreting was only recognised as a profession after the Second World War, when the Nuremberg Trials (1945-1946) in Germany and the Tokyo Military Tribunal for the Far East (1946-1948) in Japan judged war criminals in the presence of the Allies.5 A number of interpreters, found mainly amongst multilingual diplomatic and army personnel, were appointed to translate in real-time the trial proceedings to eleven different country representatives and to hundreds of legal professionals and spectators, getting to grips with a technique never used before, that of ‘simultaneous interpretation’. The technique would be made possible by technological innovations, with interpreters working in isolated ‘booths’ and connected through a cable system of headphones and microphones. The tribunals enforced professional norms of neutral, accurate rendition and of invisible positioning, so that the interpreter’s role was shaped as that of an inbetweener ensuring trust and communication between all parties without any intrusion. Institutionalised by the first United Nations General Assembly in 1946, interpreting became part of international multi-linguistic proceedings, and recognised as a stable entity. Through the involvement of local practitioners, interpreting was then officially made a profession by a process of circulation and integration that set up its codes of practice, ethical norms, associations, and training.6 However, it was at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics that interpreting in Japan gained real nationwide recognition as a fully-fledged profession, and captured the interest of public and media alike as a glamorous, exotic profession practised worldwide by multilingual individuals. Whilst I was in Japan connecting with interpreters, institutions, and organisations for data collection, I met two retired professionals who had worked at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In her interview, one of the informants, 75-year-old ‘Mariko’ recalled: “Japan’s government and the Olympic organising committee had appointed junior and senior university students with knowledge of English. Almost nobody was able to speak English at the time (laughs) and they had a very hard time recruiting interpreters. During and after the Olympics everybody got interested in interpreting, people wondered how it was possible to do it, what magic tricks lied behind interpretation”. Mariko was an exception, having picked up English in her childhood thanks to her father, who spoke it and pushed her to gain an international attitude and to later work for governmental agencies promoting foreign relations. Another participant, 74-year-old ‘Mizue’ stated instead: “They appointed me to work for the Olympics and the Paralympics. We did training for one year, and a teacher came from the US – the training was every Saturday, sometimes held at the Japanese Red Cross. We took a lot of conversation classes, to practice spoken English and get a chance to do some basic interpreting, because we seldom had chances to speak with native people. It was also a very informative experience, a lot of cultural information provided about countries and sports. I remember that I was also in charge of the ‘international club’, and assisted and translated for many people who were visiting Japan from overseas for the event”.

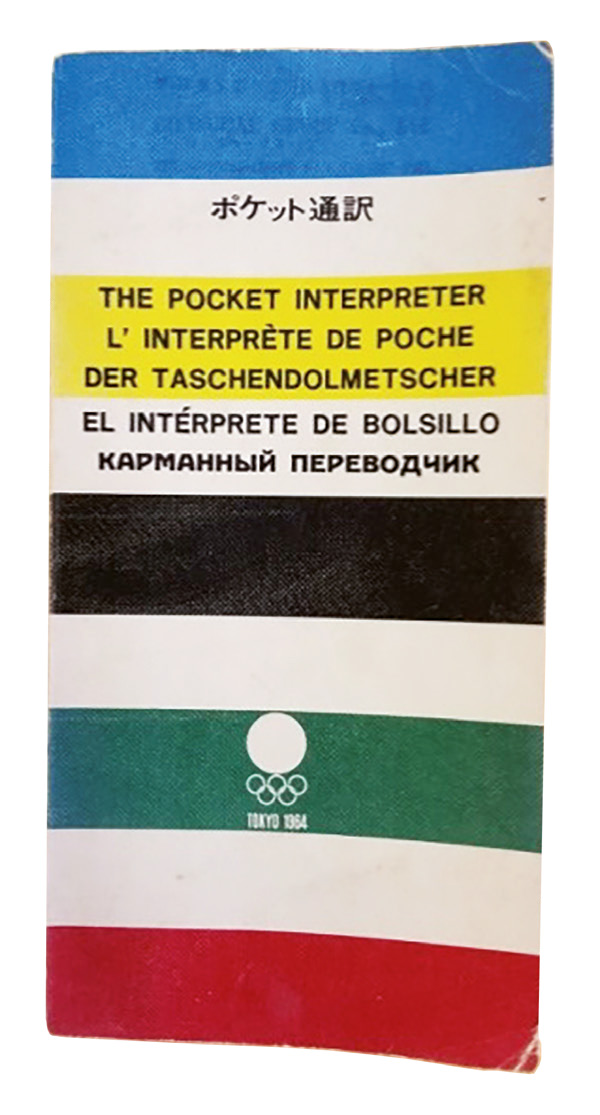

“Interpreters booklet”. Booklet used by Japanese interpreters at the Tokyo 1964 Olympics. Photo taken by author, booklet courtesy of an informant.

The 1964 Tokyo Olympics celebrated Japan’s re-emergence and progress on the world stage as an open, economically confident nation, spending the equivalent of its national budget on a major transformation project to modernise the city's infrastructure, adding momentum to a country finally showing signs of post-war recovery.7 But the legacy that lives on also symbolised the coming of age of interpreting as a thriving niche of the Japanese labour market, which recognised the importance of interpreters to bridge languages and cultures as powerful mediators beyond the Olympic events, and particularly for business and political development.

It was right after the 1964 Tokyo Olympics that Japanese pioneer interpreters acted as the driving force behind the establishment of the country’s language industry. Many of them had taken part either in the international games, or in the ‘productivity programme’ developed during the American occupation to help post-World War II Japan’s industrial recovery.8 Equipped with experience on the international stage, with foreign language knowledge, and with interpreting skills, these novel interpreters anticipated the new direction of the market for linguistic services in Japan at a time that this still did not exist. They founded the first agencies offering language and event organisation services, soon to be followed by training schools to educate the next generation of language specialists.9 As corporations, organisations, and people adapted to globalisation, interpreters allowed Japan to communicate with the world, rooting economic and cultural growth into a vast network of carefully vetted language services. The role of the language industry and the demand for interpreters has increased dramatically in Japan since the 1964 Olympics, to the point that just the 5 top language service providers alone generated a total revenue of 300 million dollars in 2018.10

Interpreting new developments beyond the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

Although the 2020 Tokyo Olympics are likely to create new waves (and awes) of demand of interpreting skills and services in Japan, the mindset required to thrive in the market is changing as well. Technological developments are reshaping the Japanese language services industry, which is increasingly working to adhere to customer-specific corporate languages, to grant terminology consistency, and to increase quality and productivity.11 The 2020 Tokyo Olympics are no exception in their attempt to connect Japan with the rest of the world, both through human and machine interpreting. As such, the games may raise fascinating avenues of inquiry regarding scenarios of innovation of the Japanese language industry, offering insights into a “further way in which lives of people hang together and co-existence takes place […] as the effect of the joint work of human practices and the performativity of materials”.12 Against this backdrop, we will have to observe the impact that interpreting at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics has on multilingual competence for understanding new directions of globalisation and interconnection in the Japanese labour market and society.

Deborah Giustini is a researcher in Sociology at The University of Manchester. Deborah’s research interests are in the sociology of work, practice theory, and translation studies, including the analysis of working and communication practices in East Asia and in Europe. deborah.giustini@manchester.ac.uk