Indigenization of Southeast Asian Buddhist Architecture: Case Study of a Burmese Monastery at Wat Upagupta, Chiang Mai

Daigoro Chihara stated that Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia is divided into three periods: (1) the period of early Indianization from the first to seventh centuries (insular) and the first to ninth centuries (mainland); (2) the golden period of maturity of Indian inspiration from the eighth to tenth centuries (insular) and the ninth to 13th centuries (mainland); and (3) the period of indigenization from the tenth to 16th centuries (insular) and the 13th onwards (mainland). 1 Although Southeast Asian Hindu-Buddhist architecture was first inspired by that of India, it underwent Southeast Asian localization from the beginning, based on available materials and craftsmanship.

The level of localization greatly increased and developed during the indigenization period starting around the 13th century in mainland Southeast Asia. This was when Buddhism began to decline in India and Sri Lanka became an important center of Theravada Buddhism, spreading it to Southeast Asia along with Buddhist art and architecture. Thereafter, Buddhist architecture in Southeast Asia was further developed, and new styles blending local beliefs and craftsmanship were created, for instance, in Thailand and Myanmar.

A Burmese Buddhist monastery at Wat Upagupta, Chiang Mai provides an example of such indigenization of Southeast Asian Buddhist architecture between the 19th and the 20th centuries. During this period, the Burmese monastery (kyaung in Burmese) was a multipurpose edifice built on piles. It combined public and private areas – namely, a Buddha shrine, an assembly hall for dhamma preaching and ceremony practice, dwelling places of monks and novices, and storage. The funds for building the monastery at Wat Upagupta were donated by U Pan Nyo who came from Moulmein around 1870-1873 and later became a well-known Burmese teak merchant in Chiang Mai and northern Thailand. At that time, Chiang Mai was a vassal state of Siam (central Thailand) and was about to be annexed by the Siamese government. Chiang Mai was formerly the capital of the Lanna Kingdom, which is referred to administratively as Northern Thailand at present. The Lanna Kingdom was founded in the 13th century and was under Burmese rule for over 200 years prior to becoming a vassal of Siam in 1774. U Pan Nyo was a wealthy teak merchant who donated money to build and renovate Buddhist architecture as well as other public works, such as streets and bridges.

Architecture built and reconstructed by U Pan Nyo had various designs, such as Shan, Pa-o, Mon, Burmese, Tai Yuan (indigenous northern Thai), and colonial styles. The important buildings constructed by U Pan Nyo between 1890 and 1910 in Chiang Mai included his house and Wat Upagupta. The monastic compound of Wat Upagupta consisted of a monastery as the principal architecture, a stupa, a Buddha shrine (wihan), and a rest house. 2 (Chiang Mai: Rajabhat University Chiang Mai, 2017), pp. 159, 161. Srisuda is a granddaughter of U Pan Nyo.] Wat Upagupta originally had two compounds, a Tai Yuan and a Burmese one. However, at present the Burmese compound has been replaced by Phutthasathan, Chiang Mai (Chiang Mai Buddhist Practice Building).

The monastery at Wat Upagupta and U Pan Nyo's house shared similarities in architectural floor plan, materials, decorations, and style, and both were built by the same group of carpenters and workers. The architectural design of his house was perhaps associated with his birth planet, Jupiter, for a person born on Thursday. This is because his house faces the west, Jupiter’s direction in Burmese astrology. The house has a north-south axis with the Ping River to the east. It was probably built by artisans from Lower Burma using two-story bungalow architecture, constructed with brick on the ground floor and wood on the upper floor [Figs. 1-3]. During the 19th and 20th centuries, bungalow-style architecture spread across polities colonized by the British, such as India, Singapore, Malaysia, and Burma. The ground floor was likely U Pan Nyo’s office, where he conducted his teak business. The living areas were situated on the upper floor, which has verandahs wrapped around the north-, west- and south-facing sides. The house originally had three outer staircases: two principal ones used separately by men and women (located to the front or west) and a minor one to the southeast that connected to a one-story kitchen on the ground level. 3

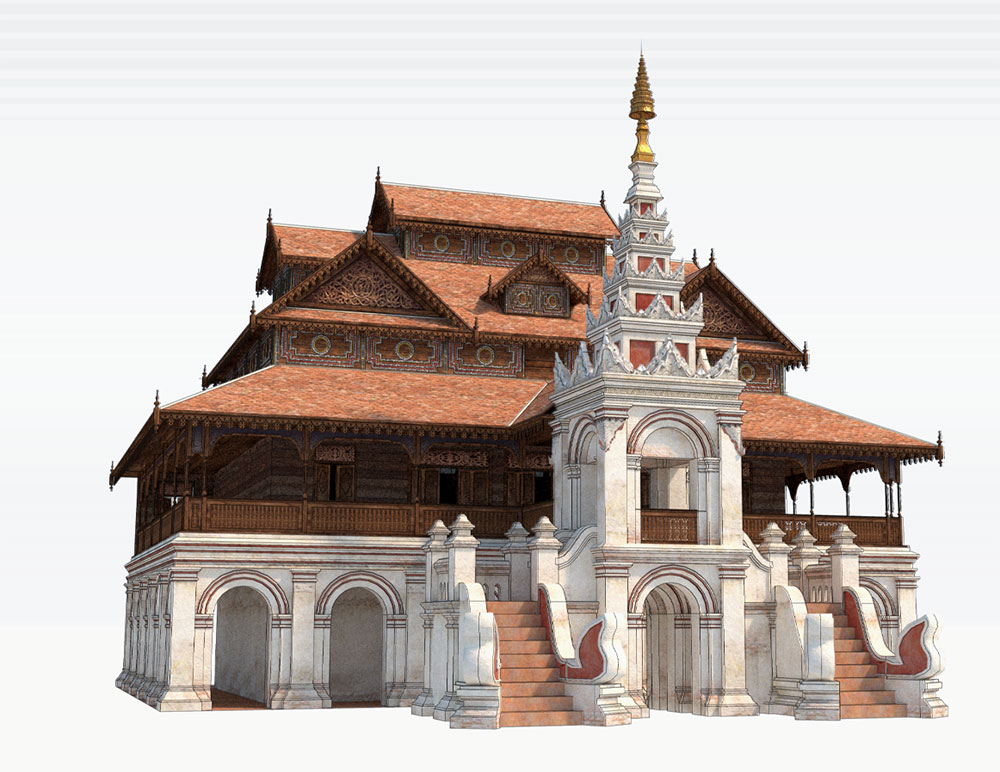

While U Pan Nyo’s house and his monastery at Wat Upagupta had corresponding elements, the monastery was more important and grander than the house. The principal roof of the monastery has two tiers, and its front porch is surmounted by a brick pyatthat (“spire”) roof [Fig. 1]. It faces north, which is the same direction that monasteries face in Lower Burma.

Fig. 1: Architectural restoration of the monastery at Wat Upagupta based on old photographs (Drawing by Patcharapong Kulkanchanachewin in 2022).

Although the monastery of Wat Upagupta no longer exists, the ground floor is assumed to have no function or to have been used as a storage facility. 4 There are three possibilities for the way in which space was organized on the upper floor: the first is parallel to the spatial organization of monasteries in Moulmein, Lower Burma; the second and third share similarities with Pa-o and Shan monasteries in Lower Burma and northern Thailand. These three types of spatial organization have a porch entrance to the north with two outer staircases separating laymen and laywomen. The upper floor was surrounded by a covered verandah on three sides facing the west, the north, and the east. However, the three types differed in terms of the location of the Buddha hall, where Buddha images were enshrined and where monks and novices had their living quarters. 5

Fig. 2: Front side of U Pan Nyo's house (Photo by Chotima Chaturawong in 2012).

Fig. 3: Back side of U Pan Nyo's house with the Buddha house shrine to the rear (Photo by Chotima Chaturawong in 2012).

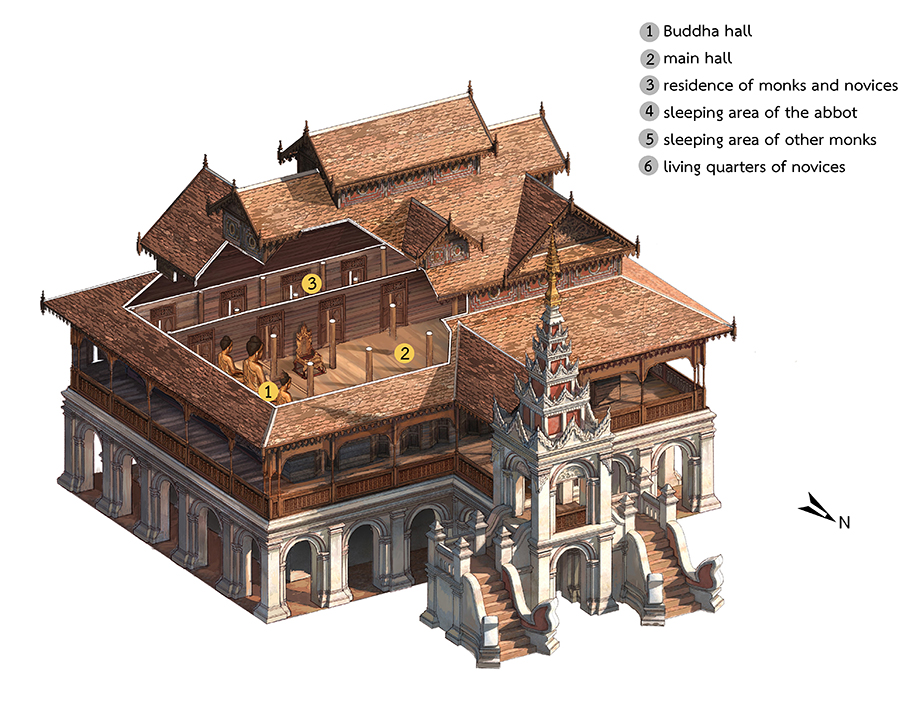

The first type of spatial organization probably placed the Buddha hall to the east and the main hall to the west. The residence of monks and novices was situated to the south [Fig. 4]. This spatial organization is typical of monasteries in Moulmein.

Fig. 4: Spatial organization of the Burmese monastery at Wat Upagupta. First possible type. (Drawing by Patcharapong).

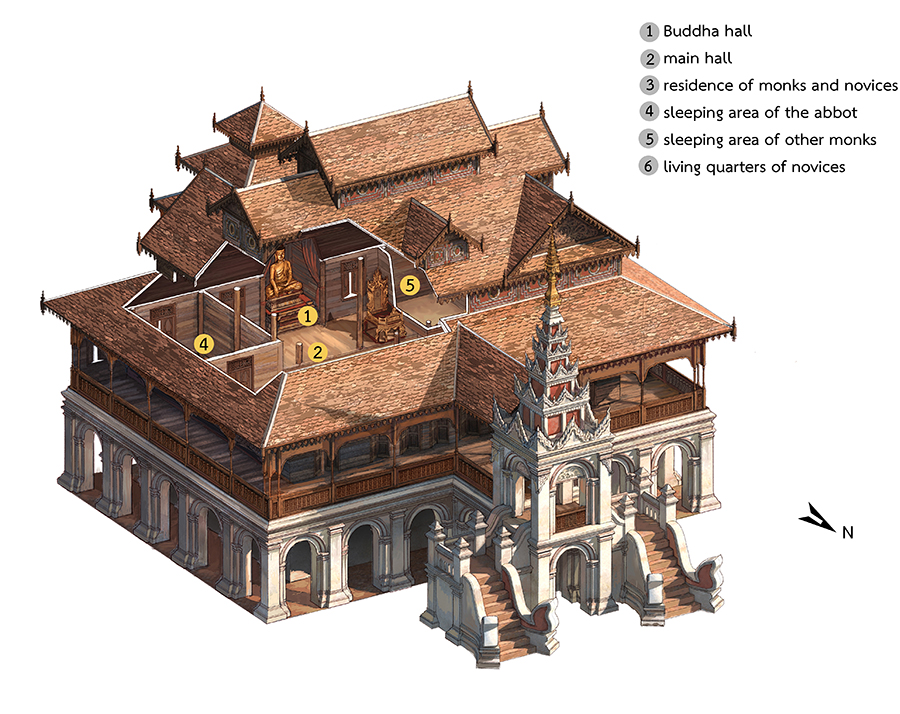

The second type of spatial organization was likely similar to that of U Pan Nyo’s house with the main hall at the center and the Buddha shrine as a detached structure to the rear. The main hall was flanked by two bedrooms to its right and left. The former to the east was the abbot’s sleeping area, while the latter to the west was reserved for other monks [Fig. 5]. These two rooms probably included a raised platform in the front, a place reserved for monks to receive guests and for novices to study. Another raised platform was erected in front of the Buddha shrine and reserved for monks and laymen. The floor plan was similar to that of Nat-kyun Kyaung, a Pa-o monastery, in Thaton, Burma. 6

Fig. 5: Spatial organization of the Burmese monastery at Wat Upagupta. Second possible type. (Drawing by Patcharapong).

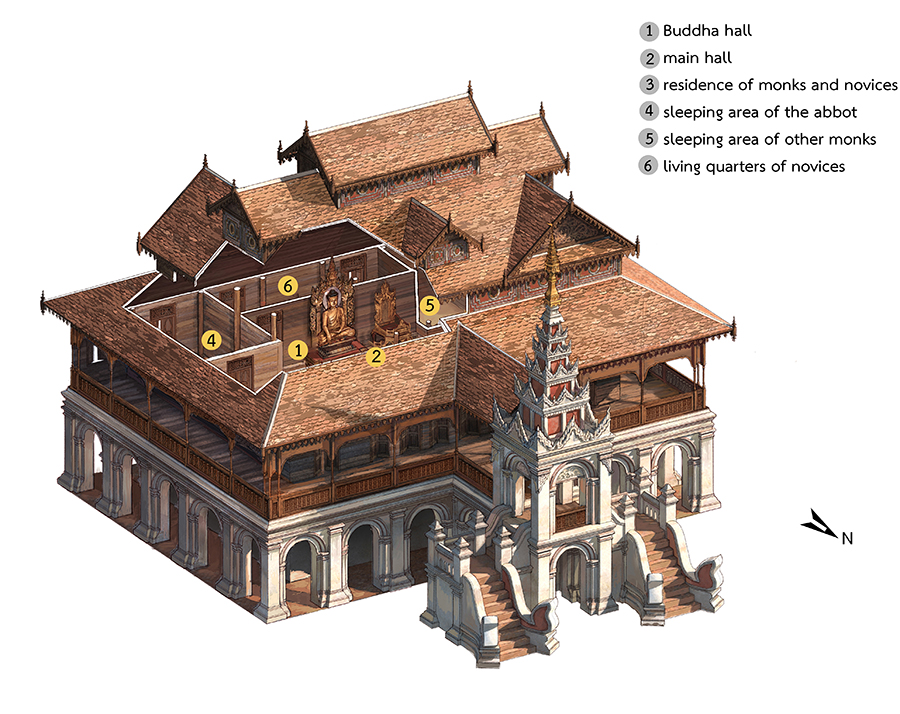

The third type of spatial organization resembled that of Pa-o and Shan monasteries in Lower Burma and northern Thailand, such as Leip-in Kyaung in Thaton and monasteries at Wat Si Rong Mueang, Lampang 7 as well as at Wat Chong Pan and Wat Nong Kham, Chiang Mai. This was similar to the second type of spatial organization mentioned above, except that the Buddha shrine was not a detached structure and to its rear were possibly the living quarters of novices [Fig. 6].

Fig. 6: Spatial organization of the Burmese monastery at Wat Upagupta. Third possible type. (Drawing by Patcharapong).

The spatial organization of the Burmese monastery at Wat Upagupta was not similar to that of the Tai Yuan in Chiang Mai, the Siamese in Bangkok and central Thailand, nor the Burmese in Mandalay and Upper Burma. Instead, it shared similarities with Buddhist monasteries of the Mon, Shan, and Pa-o in Lower Burma and provides an example of the indigenization of Southeast Asian Buddhist architecture during the 19th to 20th centuries.

Chotima Chaturawong trained as an architect and is Associate Professor in history of architecture at the Faculty of Architecture, Silpakorn University, Bangkok. Her work has focused on architecture in Myanmar, Southeast Asia, India, and Sri Lanka. Email: chaturawong_c@silpakorn.edu