How Many Hands Does It Take to Write History of Literature? The Politics of Theoretical Divergences in Indonesia

While searching for the origins of modern Indonesian literature, we come across a recurrent formulation: “modern Indonesian literature was born around 1920.” Such an assumption leads back to Dutch colonial scholar Andries Teeuw’s book Pokok dan Tokoh (1952), and it is fair to say that it has been accepted as a historical fact ever since. Accordingly, natives of what was then called the Dutch East Indies developed their literary expression due to the exertion of the educational policies of the Dutch crown, especially after the 1901 reform package known as Ethische politiek. The new colonial code not only aimed at spreading knowledge amongst natives, but also created an official publishing house called Balai Pustaka, whose goal was to monitor the ‘proper’ literary material made available for local populations.

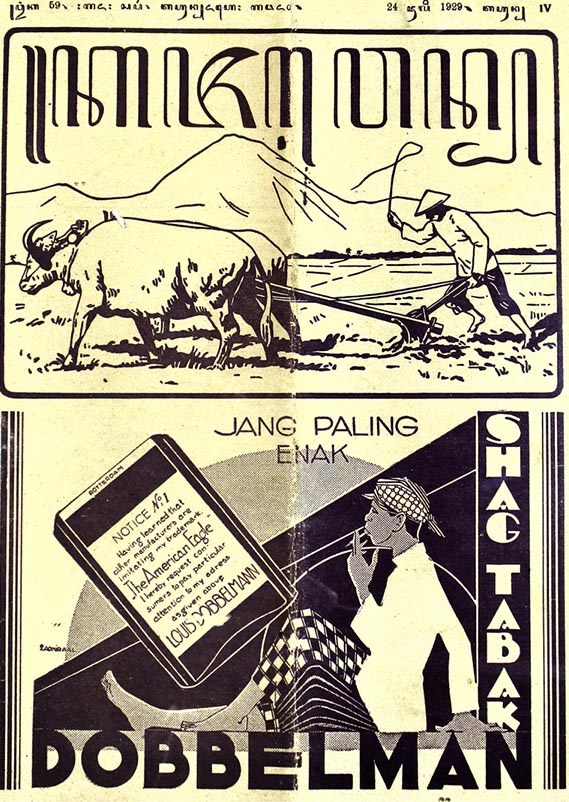

For this article, we analyzed newly-found documents that reveal the imperial goals and institutional structure of the Balai Pustaka: being directly connected to the colonial agency Kantoor voor de Volkslectuur, it performed the dual role of a Ministry of Education and Ministry of Propaganda in the Indies. The main goal was to convey Western concepts of cognition to indigenous populations, thereby outlining and establishing values, behavioral models, and new ranges of social functions. Thusly, a significant part of Balai Pustaka’s activities consisted in translating classics of Western literature into local languages. In the 1920s, it provided institutional support to native writers based in Sumatra, the same who wrote the classics of modern Indonesian expression, who were later named the Balai Pustaka literary school.

Fig. 2: Javanese-language magazine Majalah Kajawen, monitored by Balai Pustaka personnel, bringing translations of everything from Western literature classics to medical advice, Islamic prayers to advertising, second issue, 1928. (Photo by the author, 2020)

For this new literary school, the awakening of a modern conscience necessarily involved abandoning the adat, the customary norms that guide indigenous conduct within a given community. It involved replacing tradition for European values – in fact, most materials sponsored by Balai Pustaka portrayed the dilemmas faced by educated natives living under the new ‘Associationist’ regime. Marah Rusli’s Sitti Nurbaya (1922), for instance, is a privileged picture of the period’s context due to its clear-cut use of epochal stereotypes. The coming-of-age style of narrative portrays a Westernized young native struggling against regressive tribal lifestyles; indigenous life soon stops being harmonious and transforms into a life of pointless observance to traditional roles and obscurantism. Here a new Indies society is symbolized by this young man who dares to question tradition and to behave like a Dutchman – even though tribal politics hinder his personal ambitions, his example is set in paper for future readers. He is a martyr of the incomplete modernization of the Indies, so to speak.

Not all Balai Pustaka novels are pro-Associationism, though. Abdul Muis’ Salah Asuhan (1928) is a surprisingly pessimistic portrayal of the Westernizing tendencies of the time over impressionable young men. The book guides us to a poorly explored facet of anticolonial thinking during the Balai Pustaka era. The institution’s policies had many implications: one that ended up creating a monopoly over the Indonesian editorial market and stifling dissident authors and groups. Thus, examining the institution helps with the project of historical reinterpretation about the origins of literary modernity in Indonesia.

Felipe Vale da Silva, Federal University of Goiás, Brazil. Email: felipe.vale.silva@gmx.com

The full Portuguese-language version of this article originally appeared in Afro-Ásia under the title “Ficções históricas de Timor-Leste: tempo, violência e gênero na produção fílmica pós-independência” (n. 62, 2020, pp. 270-298). Available at https://periodicos.ufba.br/index.php/afroasia/article/view/35873