How is COVID-19 affecting the ASEAN economy?

The COVID-19 pandemic is first and foremost a human tragedy. By early May 2020, about 3.5 million infections and 250,000 deaths had been reported worldwide, and about 35,000 infections and 1,600 deaths in ASEAN. Measures introduced to deal with the pandemic could save lives but are having wide-ranging economic effects and inducing economic contagion.

The IMF predicts that world output will contract by 3 per cent this year, with growth in most ASEAN countries either flat or negative. There is, however, significant variation in projected growth across ASEAN this year, ranging from -6.7 per cent in Thailand to 2.7 per cent in Vietnam. In contrast, the Asian Development Board (ADB) is less pessimistic, projecting growth in Thailand at -4.8 per cent and Vietnam at 4.8 per cent. The IMF sees the ASEAN group contracting by about 1 per cent this year, while the ADB sees it growing by about the same. This variation in rates across countries, as well as between forecasters, suggests two things. Greater focus is needed on the transmission mechanisms of the economic contagion and in critiquing how assessments of the economic impacts are made. This will enable a more informed evaluation of the assessments, as the numbers keep changing, and a better understanding of the underlying processes to gauge the impacts of an uncertain and evolving shock.

Economic transmission mechanisms

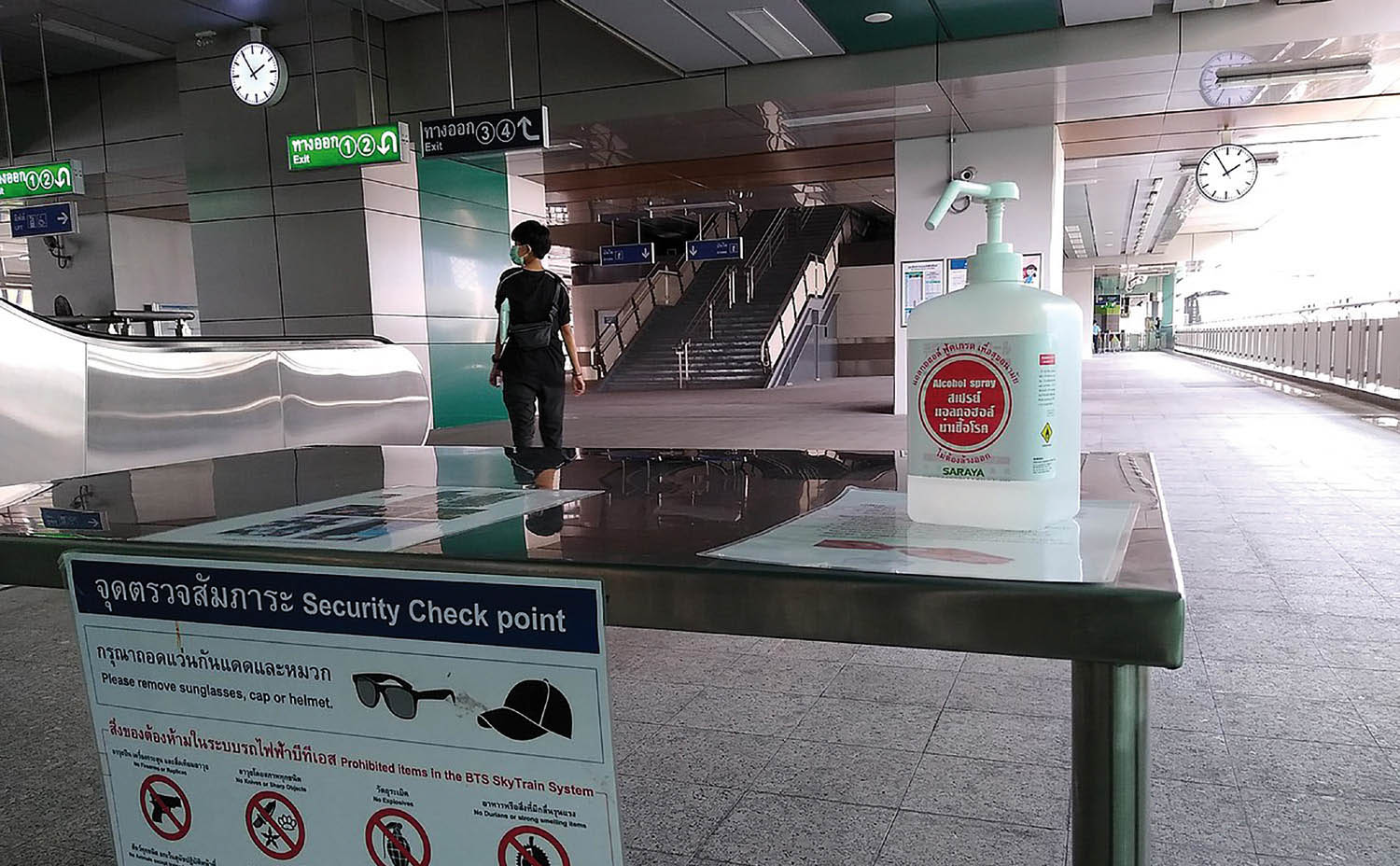

The effects of COVID-19 are hitting ASEAN economies at a time when other risk factors, such as a global growth slowdown, were already taking place. COVID-19 is disrupting tourism and travel, supply chains and labour supply. Uncertainty is driving negative sentiment. This all affects trade, investment and output, which in turn affects growth. Tourism and business travel, as well as related industries, especially airlines and hotels, were the first to be affected.1 And the conditions are worsening as more countries go into shutdown.

The supply disruptions emanating mostly from China will reverberate throughout the value chain and disrupt production. Since China is the regional hub and accounts for 12 per cent of global trade in parts and components, the cost of the disruption in the short run will be high.2 The negative effects of quarantine arrangements on labour supply could also be high depending on duration and sector.3 Manufacturing has been hit harder than service industries, where telecommuting and other technological aids limit the fall in productivity.

All these disruptions will lead to sharp declines in domestic demand. And their impact on economic growth will further propagate these disruptions. This compounding effect can magnify and extend short-run effects into the long run. The highest economic cost could come from the so-called intangibles. The effects of negative sentiment about growth and general uncertainty — which is already affecting financial markets — will feed into reduced investment, consumption and growth beyond the short run.Rolling recessions around the world now appear inevitable, despite the stimulus measures being contemplated.4 The contraction is not only likely to be greater than the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, an economic depression is on the cards. Even in a best case scenario, there will be sharp increases in unemployment and poverty. Some degree of decoupling from China, or de-globalisation in general, may also be a permanent reminder of this pandemic.

Among ASEAN countries, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand are heavily integrated in regional supply chains and will be the most affected by a reduction in demand for the goods produced within them. Indonesia and the Philippines have been increasing supply chain engagement and will not be immune either. Vietnam is the only new ASEAN member integrated into supply chains with China and is already suffering severe supply disruptions. Given time, supply-side adjustments will alter trade and investment patterns. The main adjustment will involve relocating certain activities along the supply chain from China to ASEAN countries. Although the pandemic will disrupt the relocation phase, ASEAN countries can benefit from the new investments, mitigating overall negative impacts. Vietnam and Malaysia could be major beneficiaries.5

Tourism contributed almost $400 billion to the ASEAN economy in 2019.6 Thailand and Malaysia will be most affected in ASEAN by the drop-off in tourist arrivals. Although intra-ASEAN tourism flows have been growing, spearheaded by Malaysia, the main sources of tourist arrivals are the ‘Plus Three countries’ – China , Korea and Japan – and all are contracting severely.

Cambodia and Laos receive most of their investment and aid from China, and a marked growth slowdown in China will affect them the most. A slowdown in the Plus Three countries will affect investment flows in the region as a whole.7 The Philippines and Mekong countries have large overseas foreign worker populations and restrictions on their movement or employment prospects as borders close will affect sending and receiving countries. Brunei and Malaysia are net oil exporters and the price war indirectly induced by the pandemic will hit them hard. Others will benefit from lower oil prices, as will the struggling transport sector.

Assessing the assessments

In measuring the impacts of COVID-19, it is important to separate its marginal impact from observed outcomes. This is important because the remedy may vary depending on the cause of the disruption. This requires an analytical framework that can measure deviations from a baseline scenario that incorporates pre-existing trends. A model-based analysis, rather than casual empiricism, is required to reduce the problem. In addition, what is explicitly modelled and what is assumed, and what those assumptions are, need to be considered in understanding differences in projections.

Even before the outbreak, risks of a global growth slowdown were rising. The restructuring of regional supply chains had started, driven initially by rising wages in China and accelerated by the US–China trade war.8 While COVID-19 may further hasten the pace and extent of the restructuring, it is only partly responsible for what may happen. It would be misleading to attribute all of the current disruption to COVID-19. Had the trade war not preceded it, COVID-19 may have resulted in greater disruption to supply chains. Any assessment of impacts must recognise that the spread of COVID-19 is unpredictable, and so too the response by governments. It is difficult to estimate the impacts of a shock that is uncertain in itself. This reiterates the need for rigorous modelling and scenario analyses.9 The current trend points to risks rising, often accelerating, as with previous epidemics. This uncertainty underscores the need for caution in assessing, and regular recalibration in producing assessments.

Jayant Menon is a Visiting Senior Fellow in the Regional Economic Studies Programme at the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.