Home and the World at Museum Van Loon: A Conversation on Curation and Colonial History with Thomas Berghuis

Thomas Berghuis is a curator and historian of Asian art based in the Netherlands. Berghuis recently curated the exhibition Home and the World in Museum Van Loon, an historical building in the canal district of Amsterdam. In this exhibition, fourteen contemporary artists from all over the world used different spaces of the Van Loon canal house to explore the intricate connections between colonialism and nationalism, past and present. In this conversation, Berghuis elaborates on the themes of the exhibition, on its peculiar location, and on the importance of alternative perspectives on how to feel at home in a world beyond the colonial state and the nation-state. In addition to thanking Thomas Berghuis for this interview, we are grateful to Johan Kuiper and Victor van Drielen at the Museum Van Loon for providing images and soundbites from the exhibition.

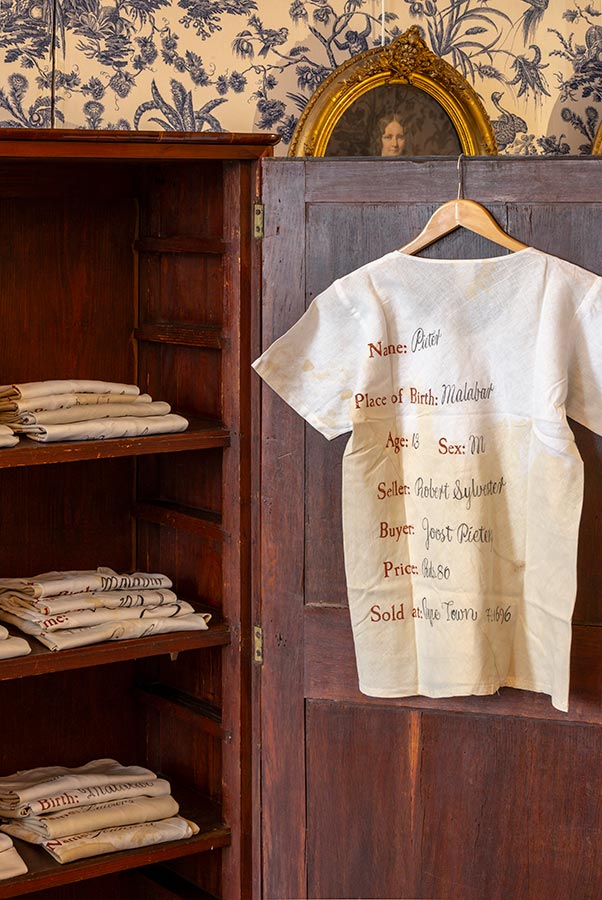

Paramita Paul (PP): Let me start our conversation today by sketching a scene for you: I am standing in Museum Van Loon’s garden, a beautiful, green, and quiet space between the main Van Loon house on the Keizersgracht canal in Amsterdam, and the coach house, which is also part of the Van Loon premises. Hung to dry in the garden are white cotton work garments. At first glance, there is nothing strange about them, except for the fact that it is slightly odd to find laundry hung to dry in a museum garden. Upon closer inspection though, we notice that each of the garments contains the personal information of an individual, including their name, gender, age, and place of birth, as well as their buyer, their seller, and their price. The piece of cloth I am looking at mentions the name of “Dominga” from Bengal, who was sold by Cornelis Kelleman to Jan Dircx de Beet in 1693. For me, this artwork, One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale by Sue Williamson, was one of the most poignant pieces in your exhibition. Can you elaborate on this piece and use it to introduce the overall theme of Home and the World?

Thomas Berghuis (TB): Museum Van Loon is also well known for its garden. But for a lot of people, including some of the artists that participated in the exhibition, the house of the Van Loon family, as well as other houses in this context – they're almost haunted houses, because of the colonial history, imperial history, and, as this exhibition is proposing, also a national history. […] So the piece of Sue Williamson is one of the keys in linking various histories. It connects, first of all, to the memorial year of the abolition of slavery in what they call the Dutch Kingdom – so the commemoration of 150 years since the abolition of slavery. What Sue Williamson has done is that she's been exploring various histories.

Fig. 2: One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale (2018), by Sue Williamson. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

After 1815 when the Dutch Kingdom is founded, the Van Loon family is very close to the Dutch Kingdom. They also are part of the Dutch trade organization, Nederlandsche Handelsmaatschappij. They are actually at the table to advise companies and advise traders on the cultivation system in Indonesia or what have you. They build up during the East India Company, West India Company, to continue that as a state enterprise and as an enterprise linked to the Dutch Kingdom. A lot of colonial histories and colonial archives are now being explored and being opened up.

PP: Another central theme in One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale and across the exhibition is the connection between the individual and the world. How does the exhibition approach that connection?

TB: All of the works in the exhibition – I started to realize when we built them up and when we hosted them in Museum Van Loon – have a very personal touch and a personal link to the artist that made the work. Researchers connected to IIAS will recognize that space when you're alone in an archive and you're doing this tedious work; that's what these artists are doing as well, and they created out of that artworks that become very personal like in the case of Sue Williamson. Another example which is a very personal work is the work that is in the Carriage House of Van Loon: The Patterns of Displacement in the Context of Home, which asks us to reflect on the notion of home and having a home in the world. It brings us into contact with a refugee tent cut into pieces, each piece has the name of a refugee on it. […] What I'm hoping with this exhibition is that eventually we start to realize that there may be not only decolonial strategies, but also de-national strategies, and those de-national strategies really de-linking the nation-state are necessary in terms of what I want: urgent calls for solidarity, communities, society of solidarity, international solidarity as well as local regional solidarity. I'm not the only one, I mean Rabindranath Tagore – who is a part of this exhibition – he was also searching for that.

Fig. 3: Epicycles IV & V (2021), by Jitish Kallat. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

PP: You introduced Tagore basically in the first room of the main building, where there is an area dedicated to the renowned poet, writer, and philosopher whose 1913 novel Ghare Baire, or “At Home and Outside”, inspired your exhibition Home and the World. Can you introduce us briefly to Tagore's ideas in Ghare Baire? How were his ideas relevant at the time of publication versus now?

TB: There's a tremendous amount of studies written on the history of the British Empire, and there's a lot of studies written on the history of the nation and Tagore's change, but after Ghare Baire he writes a series of lectures, in which one is on the nation, and that's where he really compares the nation-state, a Western construct but also a construct of power and greed to a country and its people. This is what the crux is of Tagore in the 20th century. I'm not an expert on Tagore at all, but what I find important is that amidst this thinking, thinking of a possible future, he establishes in 1901 a world school in Santiniketan and that later becomes a university. He travels the world and speaks to a lot of other intellectuals. He sees the rise of ultra-nationalism. So this is what Tagore sees, and he sees it as a big problem for the world ahead, and I'm saying basically by bringing his words back he was right and we should listen to him. I mean, I couldn't have imagined the world that we are living in today when I started this exhibition even seven years ago. The amount of nationalism that has arisen since 2017 has been frightening.

Fig. 4: Kerubut (2024), by Iftikhar Dadi & Elizabeth Dadi. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

Fig. 5: Karkadé (2013), by Iftikhar Dadi & Elizabeth Dadi. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

PP: Each artist subtly appropriates a particular area of the building – subtly, yet with clear links for the viewer to see all kinds of connections. The sort of obvious elephant in the room is the museum building, the Van Loon house, as the center for all of this. In 1602 William van Loon was one of the founders of the Dutch East India Company, and his descendants still live on the canal house’s upper floors. It is very intriguing to organize this exhibition at that particular site. Can you say more about the marriage of that place of the museum and Home and the World?

TB: It’s fortunate that the family – Philippa Van Loon and Martine Van Loon – is very open to this process, so both have said that what is being done by these artists is absolutely necessary and they find it meaningful and intriguing. The other fortunate thing in with working with Museum Van Loon is that it's a small team of very dedicated people, and they realize these interwoven histories, speak to the people that visit the museum, and are open to questions.

Fig. 6: KANAVAL (1995 - ongoing), by Leah Gordon. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

Fig. 7: Les Eclaireurs (2009) & No Names Please! (2017), by patricia kaersenhout. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

PP:Home and the World is not your first project at Museum Van Loon. At the end of our conversation today, I'd like to look ahead and focus on your current collaboration with Museum van Loon called Wereldschool, in which you are working with international partners across different continents. What is the Wereldschool, and how will you develop it in the coming years?

TB: So the Wereldschool, the World School, is basically a proposition that originates with Tagore, in the sense that he set up a nest in which the world comes together in Santiniketan. And I was thinking, what could we do today to both honor his ideas, as well as to extend it? What would Tagore have done? Tagore was very much aware that he was of a privileged class, so he could travel and be in touch with other intellectuals. But I think what he meant to do was to bring people together, also lower classes and people who don't have that privilege that he had. And I was thinking, what would he do today? What I decided – following inspiration from collective initiatives in art and culture in Southeast Asia and South Asia – is that a lot of artists are saying we should create viral systems and systems of hacking. The World School is something that everyone can claim, can own, can run, can disseminate. We are creating four time slots of two hours online, on one single line. We made these time slots open, open for participation and leading from a keynote, which is often done by one of the artists in the exhibition. The conversations are open and unrecorded, so that it allows the possibility of bringing especially young scholars as well as arts professionals and their community members together in an open, conversational, safe environment. And we talk about the possibility of leading communities of solidarity beyond and after the nation-state. So, we're a bit rebellious, I guess. […] But important with the World School, I'm now saying that research, archival research, transhistoric research, intercultural, transcultural research, should be taken collectively. Let's create open-source environments for research, in which text-based researchers can play a role, but also image-based researchers, so contemporary artists can play a role. It's being tested now in the Netherlands. There is talk of a new collective in which artists, art and scientific research will collaborate. But I'm very critical of this new endeavor that is being led by an exclusive view and an exclusive group of people, because it's very technical. And what I think we need is to protect humanities. So yes, here we are talking from IIAS, which is within the context of the humanities, the arts, arts and society, arts and politics. And these are the fields that we should endorse. And I'm seeing within the current world a lot of emphasis being done on the hard sciences, the technical sciences, including in the relationship to art. So let's work with artists.

Fig. 8: Mom 몸 (2024), by Minouk Lim. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

Fig. 9: If Water Has Memories (2022), by Tiffany Chung. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

Fig 10: Oso Dresi (2024), by Raul Balai. Photo: Thijs Wolzak (courtesy of Museum Van Loon, 2024)

This transcript has been heavily edited and abridged. The original audio includes a wealth of further details and discussion. To hear to the full conversation, listen and subscribe to The Channel podcast: https://iias.asia/the-channel

The Channel is the flagship podcast from the International Institute of Asian Studies (IIAS). Each episode delves into a particular Asian Studies topic from across the social sciences and humanities. Through a mixture of interviews, lectures, discussions, readings, and more, The Channel is a platform to connect scholars, activists, artists, and broader publics in sustained conversation about Asia and its place in the contemporary world. Listen and subscribe at https://iias.asia/the-channel or on your preferred podcatcher app.