Heritage diplomacy along the One Belt One Road

<p>Today the preservation and commemoration of cultural heritage in Asia occupies a complex place in an increasingly integrated and interconnected region. In comparison to ten years ago we are seeing a significant growth in the level of international hostility concerning the past and its remembrance. Histories of conflict, for example, are the source of ongoing tension in East Asia at a time of escalating militarisation. The diplomatic tensions between Japan, Korea and China concerning the events of World War 2 are being further exacerbated by the approach of museums in the region and attempts to have remnants - whether it be buildings, letters or landscapes - recognised by international heritage agencies. At the same time, however, we are also seeing major growth in the scale and scope of international cooperation between countries across Asia regarding the preservation of the past. Heritage conservation is fast emerging as an important component of the intra-regional economic and political ties that are binding states and populations in the region. In the coming decade one initiative in particular will take this heritage diplomacy to a whole new level, China’s One Belt One Road. </p>

In 2014-5, Japan successfully added two industrial sites to the World Heritage List. Their nominations followed very different pathways. The first, the ‘Tomioka Silk Mills and Related Sites’ passed through smoothly, with India and Turkey among those praising Japan for highlighting silk and sericulture as ‘the common heritage of mankind’. A year later however, the nomination of ‘Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution’ located in the Kyushu-Yamaguchi region sparked controversy within the committee and significant consternation for UNESCO and its world heritage office. The nomination included factories that used Korean forced labour during World War II, a time when the Korean peninsula was under Japanese occupation. Japan’s unwillingness to acknowledge this led to anti-Japanese protests in South Korea and China and prolonged diplomatic tensions in the region. The dispute over Kyushu-Yamaguchi also received considerable press attention around the world. But while Tomioka passed largely unnoticed, I would suggest it is this nomination, and the nature of its endorsements, that will have far greater consequences over the longer term.

For a number of decades Japan has successfully utilised culture and cultural heritage as a mechanism for advancing its foreign policy and soft power strategy.1 Within South and Southeast Asia alone, Japan currently has heritage related projects in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, and Vietnam. Today, however, they are far from alone in folding heritage diplomacy into their bilateral and multi-lateral programmes of cooperation and aid. China, India, and South Korea are among those spending heavily on heritage diplomacy to secure influence in the region. South Korea, for example, is investing in a number of institutions designed to provide expertise both domestically and overseas. The Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea, an independent government agency since 1999, has moved beyond its original domestic remit by signing around 60 bilateral agreements with organisations in more than a dozen countries over the last decade or so.

India is similarly expanding its cultural interests in Southeast Asia. For some time India has provided assistance to Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos in an array of heritage sectors, including archaeology, textiles, museums and modern urban architecture. More recently however, such forms of cooperation have been explicitly mobilised as a mechanism for promoting economic and diplomatic relations, with Myanmar offering a case in point. Concerned by the growing influence of China in the country, the Indian government began folding archaeology into its official diplomatic visits from 2010 onwards, invoking ideas of mutual pasts to build trust and diplomatic ties.

This growth in heritage assistance is occurring in tandem with a rise in intra-regional aid and trade. The development sector, which has historically been driven by bilateral and multilateral agencies headquartered in Europe or North America, is now being transformed by new forms of intraregional cooperation and assistance. As a result, the cartographies of influence and power across the networks of heritage diplomacy are also shifting. The rapid rise in intraregional tourism since the early 2000s also means Asia’s governments can use overseas cultural aid as a mechanism of public diplomacy that reaches multiple audiences.

It is a set of changes academia has been slow to respond to. In the critical analysis of Asia’s heritage, the focus often remains on certain agencies, actors and places. UNESCO, for example, has been the subject of countless publications and dissertations, often critically analysed in relation to questions of western neo-colonialism or the role its policies play in shaping nationalism, economic development or memory in Asia. The concept of heritage diplomacy moves the analysis of cultural heritage in the region in productive directions.

One Belt One Road

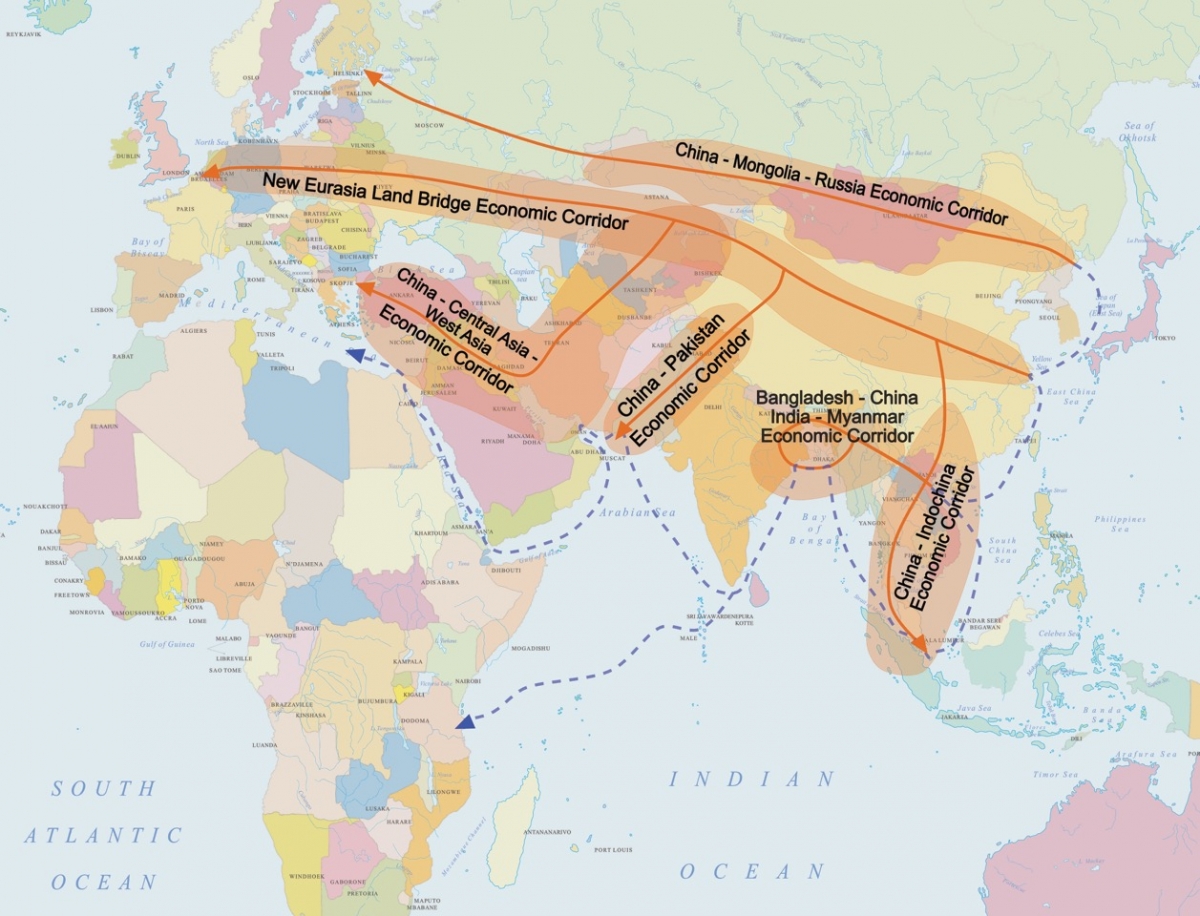

One project that exemplifies the trends outlined here is One Belt One Road. Launched by Xi Jinping in September 2013, the project has been described as “the most significant and far-reaching initiative that China has ever put forward”.2 Five major goals sit within a broad framework of connectivity and cooperation: policy coordination; facilities connectivity; unimpeded trade; financial integration; people to people bonds.3 Although recognised as an important mechanism for deepening bilateral and multilateral cooperation, this final goal has received less media and expert attention in large part because its projects do not carry the spectacle of multi-billion dollar infrastructure investments and contracts, or the mega-project outcomes they produce. In contrast to the ‘harder’ matters of trade agreements, physical infrastructure or reforms in legal systems, the people-to-people elements of the project are passed off as a series of ‘softer’ outcomes. Moreover, where such issues are discussed they tend to be vaguely accounted for as Chinese ‘soft power’, an analysis that misses the complex role culture and history play in the initiative. Indeed, I would suggest for both China and many of the countries involved, in cultural and historical terms much is at stake in this project.

In recent years a growing number of experts have pointed to the role deep history plays in China’s conduct of international affairs today. The long game, it is suggested, is overcoming a century of humiliation, a sense of national weakness at the hands of oppressive powers, and securing international recognition for Chinese civilisation and its impact on world history. The question thus arises regarding how the state conveys and communicates such ideas today, both domestically and to the outside world. Cultural heritage has become a powerful and important platform in this regard. The Chinese government is investing significant resources to connect present society to its past by establishing museums, festivals, expos, and countless intangible heritage initiatives. Perhaps most significant here though are its urban, monumental and archaeological cultural properties, thirty four of which are recognised by UNESCO as being of Outstanding Universal Value and thus worthy of its prestigious World Heritage List.

Now in its fifth decade, the list has inadvertently become a marker of not just national, but civilisational standing. States around the world are pursuing world heritage in order to promote particular forms of cultural nationalism and civic identities at home. At the international level, it has emerged as the cultural Olympics of history, with much energy going into ensuring the worlds of European, Persian, Arab, Indian or Chinese pasts are given the recognition they deserve. China ranks second in the global league table of listed properties, and the Silk Road will help it eclipse Italy in the prestige stakes of culture and civilisation. As David Shambaugh has indicated at length, culture has become an important pillar within China’s strategy to secure influence internationally, with Xi Jinping dedicating a plenary session of the 17th Central Committee of the CCP to the issue in 2011.4 Nowhere is this more important than within the region itself, where there are deep seated suspicions about China’s economic and military rise. I would suggest that it is within this wider context that we need to situate the Belt and Road strategy of fostering people-to-people connections.

Moreover, we need to look to the ways in which a historical narrative of silk, seafaring and cultural and religious encounters also opens up a space for other countries to draw on their own deep histories in the crafting of contemporary trade and political relations. Iran, Turkey and the Arab States of the Persian Gulf are among those looking to Belt and Road as an expedient platform for not only securing international recognition for their culture and civilisations, but also using that sense of history to create political and economic loyalty in a region characterised by unequal and competing powers. The now conventional idea of soft power focuses on how states and countries secure influence through the export of their own social and cultural goods. But this idea only partially captures what is at stake in One Belt One Road. Reviving the idea of the silk roads, on both land and sea, gives vitality to histories of transnational, even transcontinental, trade and people-people encounters as a shared heritage. Crucially, it is a narrative that can be activated for diplomatic purposes.

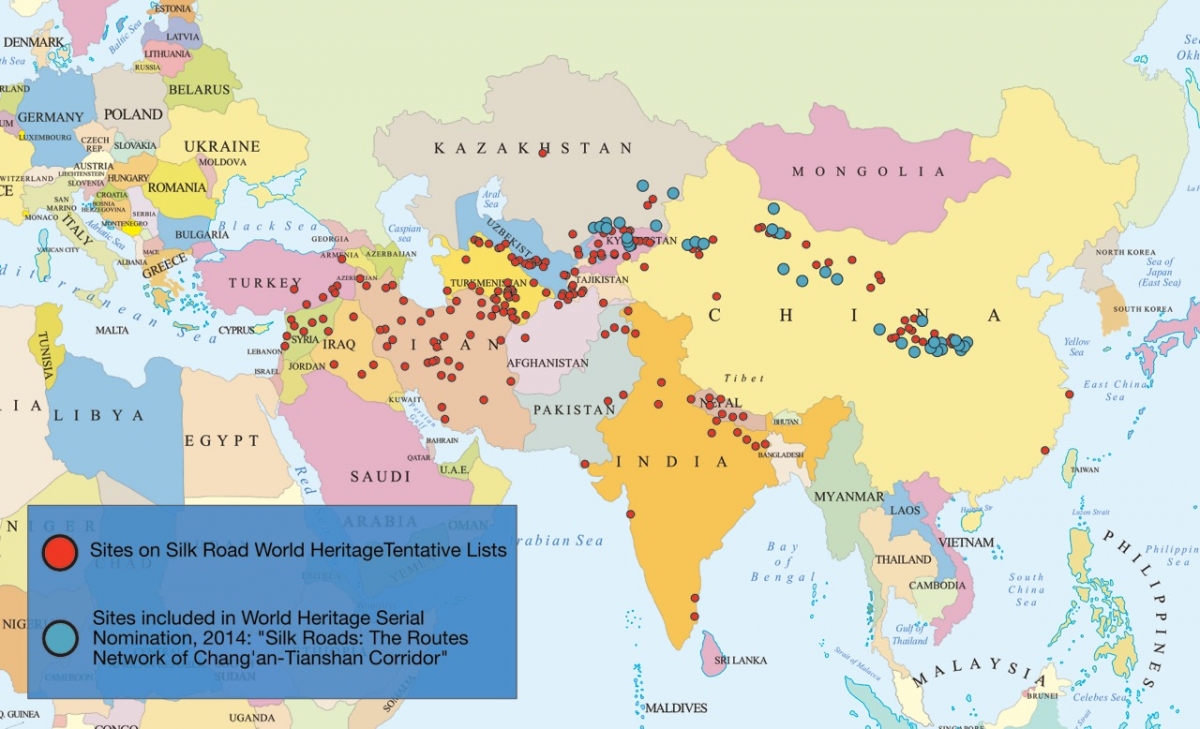

In their participation at UNESCO’s annual world heritage committee meetings, state parties now regularly use this language of shared heritage to endorse each others’ nominations. World heritage has thus become an important platform for identifying trade, religious and other connections from the past as the basis for future cooperation. It is an arena that explicitly encourages states to be internationally disposed, wherein norms of cooperation rely upon internationalised cultural nationalisms and the building of bridges as a platform for strengthening bilateral relations. While the idea of Silk Road nominations formally commenced in 2003, we are now seeing a surge in activity with Belt and Road dramatically changing the political impetus for cultural sector cooperation. Financial support from the governments of Japan, Norway and South Korea contributed to the first successful Silk Road world heritage listing in 2014. The nomination involved government departments and experts from China, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan cooperating over thirty three separate sites. In November 2015 the fourteen country members that currently make up the Silk Roads Coordinating Committee gathered in Almaty, Kazakhstan to plan future nominations and tourism development strategies. Given dozens of Silk Road corridors potentially linking more than five hundred sites across the region have been identified, the Silk Road is likely to emerge as the most ambitious and expansive international cooperation program for heritage preservation ever undertaken.

Heritage diplomacy as hard power

Collaboration over nominations is only a small part of a much larger trend towards international cooperation for heritage preservation in Asia. Numerous world heritage sites across Asia have become honeypots of development in the past twenty years, and provided the logic for the construction of airports, roads, hotel zones and various forms of urban redevelopment. Increasingly tied to infrastructure, urban planning, tourism, post-disaster reconstruction and conflict transformation, heritage has thus emerged as an important form of spatial and social governance. The provision of cross-sector bi-lateral aid in this space also complicates any distinction between soft and hard power. This is evident in the apparent alignment of Silk Road heritage nominations with the multilateral structures of cooperation now proposed under the ‘Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ issued by the Chinese government in early 2015. A proposed South Asian Silk Road nomination largely corresponds with Belt and Road’s Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor, and plans for a Central Asian heritage corridor involving Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan directly align with the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor.

Central to all this is tourism, an industry that uses people-to-people connections to link the cultural past to economic development. Over the next twenty years the Asia Pacific region will be the key driver of growth in a global tourism industry forecast to reach 1.8 billion international arrivals by 2030 (from around 1 billion currently). Rising middle classes in Asia, most notably China, will populate the airports and hotels built along the Silk Road opening up previously remote regions and communities. As a transboundary cultural landscape, the Silk Road will become a network of corridors and hubs of tourism development, oriented in large part around the branding of world heritage. As low and middle income countries in South and Southeast Asia have demonstrated in recent decades, international tourism has become a significant factor in GDP growth.

For the Silk Road, the UN World Tourism Organisation is working with thirty three states, spanning Southeast Europe to Southeast Asia, and the Middle East to East Asia, to align their tourism development strategies. In reversing long standing policies based on anxieties about regional counterparts or previous geopolitical alignments, many of these member states are now reforming visa regulations to facilitate greater leisure mobility and a less bureaucratic experience for tourists moving across multiple jurisdictions. Xi’an in northwest China has developed an ambitious heritage tourism strategy that capitalises on its location as the starting point of the original Silk Road. Projects now in development include the ‘Silk Road International Museum City’ and ‘Silk Road Expo Park’. Museums and pavilions will exhibit the arts, crafts and archaeological artefacts of more than twenty Silk Road countries. In this regard Xi’an aims to be the gateway for a new era of intra-regional tourism.

In such examples we also begin to see how prioritising people-to-people connections, both domestic and cross-border, ties into the security dimensions of the Belt and Road initiative. One of the lessons of the original Silk Road was that cross-border trade and cultural exchange build mutual respect and trust. Of paramount importance to Beijing is the stability of its western provinces, and transforming Urumqi and Kashgar into commerce and transport hubs – and the wealth generation that affords – will integrate the Muslim Uighar communities of the region with the rest of the nation. Indeed, the recent history of Tibet and Lhasa provides a likely template of the cultural politics in play here. As cross-border and domestic tourism brings business opportunities to these regions it is highly probable that Han Chinese migration into the area will also increase. Moreover, for Beijing and the governments of Central Asia the spectre of Islamic fundamentalism demands policies that turn long, and in many cases porous, borders from being a threat into an opportunity for creating the types of social stability that come from economic prosperity. For many in the region, the Silk Road is a story of peaceful trade, and a rich history of religious and harmonious cultural exchange. Belt and Road seeks to directly build on this legacy. It rests upon a historical narrative that connectivity – both cultural and economic – reduces suspicion and promotes common prosperity, an idea that is being eagerly taken up by states concerned about civil unrest, both within and across their borders. In November 2015, Nursultan Nazarbayev, President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, chose UNESCO’s headquarters, Paris to announce the country’s new ‘Academy of Peace’, stating that “we can best counter extremism through inter-cultural and inter-religious dialogue”.5

The Maritime Silk Road

The situation of the overland Silk Road is mirrored in the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The 2015 Visions and Action plan calls for two transboundary maritime economic routes, linking deep water ports across the South China Sea, Indian Ocean and beyond. It has been extensively documented that both China and India are competing to build networks of maritime infrastructure across these regions, amongst growing anxieties over freedom of navigation rights and the need for strategic locations for seaborne trade.6 In response to the Chinese financing of deep water ports and Strategic Maritime Distribution Centers in littoral regions across Africa and South America, India has increased funding to its navy and maritime defence capacities. Against this backdrop sits heritage diplomacy, with China and India assembling countries in the region for maritime themed world heritage nominations, namely the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ and the Indian Ocean ‘Project Mausam’ respectively.

As Erickson and Bond have noted, maritime archaeology has formed part of China’s strategy for claiming territory in the disputed South China Sea.7 Various maritime archaeology institutes including the National Center for Conservation of Underwater Cultural Heritage, together with ships and submersibles equipped for deep water shipwreck hunting, have endeavoured to find material evidence in support of claims for territorial jurisdiction over the East and South China seas based on historical right. In contrast to many Western expert commentaries that point to twentieth century laws and treaties, within China discoveries of porcelain and other artefacts dating as far back as the ninth century Tang dynasty substantiate the country’s position over the disputed waters.8 Crucially, however, the notion of a Maritime Silk Road flips this excavation of shipwrecks from mere evidence of historical presence towards a much larger, and more diplomatically expedient language of region-wide trade, encounter and exchange. Belt and Road’s emphasis on maritime connections also sustains claims that China ranks alongside its European counterparts as one of the great naval powers in world history.

One figure in particular, Admiral Zheng He, embodies this grand narrative. A Muslim eunuch who led seven fleets across to South Asia, the Arabian peninsula and West Africa between 1405 and 1433 during the Ming dynasty, Zheng He is widely celebrated as a peaceful envoy in both China and by the overseas Chinese living in Malaysia, Indonesia and elsewhere. In addition to the museums, mosques, and artefacts now appearing around the region celebrating his voyages, China has given millions of dollars to Sri Lanka and Kenya to support the search for remains of Zheng He’s fleet. Both countries are key nodes in the Belt and Road infrastructure network, with China financing the construction of deep water ports in Colombo and Hambantota in Sri Lanka, and Lamu in Kenya. In 2005 Singapore also celebrated the 600th anniversary of Zheng He’s voyages, hosting multiple events over the course of the year.9 These helped raise public awareness about Singapore’s maritime history and connections to China; an historical narrative political leaders now explicitly invoke to garner domestic support for Singapore’s strategic engagement in Belt and Road. Given the networked nature of the initiative, over the coming years we will see other states in the Persian Gulf, East Africa, and South-Southeast Asia excavate – both physically and discursively – their own maritime pasts and build heritage industries and museums around stories of trade, connection and exchange.

The connections of silk

By speaking to the construct of the Silk Road, One Belt One Road sits on a deep history of cultural entanglements and flows, which countries across Eurasia and beyond can buy into and appropriate for their own ends. As a bridge, this complex trans-boundary cultural history is reduced to a series of heritage narratives that directly align with the foreign policy and trade ambitions of governments today. The Silk Road is a story of connectivity, one that enables countries and cities to strategically respond to the shifting geopolitics of the region and use the past as a means for building competitive advantage in an increasingly networked Sinocentric economy. Culture forms part of the international diplomatic arena now, and with routes, hubs and corridors serving as the mantra of Belt and Road, countries will continue to find points of cultural connection through the language of shared heritage in order to gain regional influence and loyalty. But this also raises important questions concerning new forms of cultural erasure and coloniality and the political violence they deliver. The lives of vulnerable communities, particularly those located in borderland regions, will be deeply affected by the developments outlined here. In both its land and sea forms, Belt and Road gives impetus to a network of heritage diplomacy that fosters institutional and interpersonal connections. This in turn provides the foundation for the more informal people-to-people connections that will lie at the heart of Silk Road tourism. Indeed, framed by the political and economic imperatives of One Belt One Road, there is a distinct possibility that the heritage diplomacy of silk will have lasting consequences that far outlive the tensions of twentieth century conflict and occupation.

Tim Winter is Research Professor at the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University, Melbourne. He has published widely on heritage, development, urban conservation, tourism and heritage diplomacy. He is President of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies and been a Visiting Scholar at the University of Cambridge, The Getty and Asia Research Institute, Singapore. His recent books include The Routledge Handbook of Heritage in Asia and Shanghai Expo: an international forum on the future of cities. He is currently working on a book on heritage diplomacy (tim.winter@deakin.edu.au).