From the heart to the plate. Debates about dog meat in Dimapur

Dimapur is not an easy city to govern, with or without dogs. Close to 400,000 people live here and an increasing number of people from rural Nagaland are moving to Dimapur in search of livelihoods. It is the largest city in Nagaland and possesses the only airport and railway station in the state, making it the biggest commercial hub. Between 2001 and 2011, the city’s population tripled, leading to rapid urbanization and an unplanned construction boom fueled by a conflict economy. Given that the Naga people in Nagaland, like in other tribal states, are exempt from paying taxes to the government of India, the city has become a safe haven for money launderers and tax-evading business agencies.1 Dimapur is also the only city in India where two ceasefire camps of rival Naga insurgents are located adjacent to Indian security camps and headquarters. Factional shootings and killings in the heart of the city, unclaimed dead bodies, and the presence of Indian armed soldiers in public spaces, are common. Walking around Dimapur is a visceral experience of militarization and violence. It is not a city that attracts conversation about gastronomy. There are no animal farms, flourishing food industry, or a culture of fine dining.

The heart of the matter

Yet, conversations about cruelty towards dogs and the practice of eating dog meat in Nagaland have gathered momentum with pictures and videos taken in a location known as Super Market in Dimapur. A line of bamboo sheds from where women traders sell dog meat have motivated tourists, journalists and animal rights activists in India to highlight the inhumane practices of dog meat trade in the state. In 2016, the dog meat debate attracted the national limelight when a legal notice was served to the government of Nagaland to stop the use of dog meat as food.2 When reports about the dog meat trade appeared in newspapers and on social media across India, it was immediately condemned as a cruel practice. The images of dog meat in Nagaland became part of a standard strategy used by animal rights activists to portray consumers of dog meat as, “…the most despicable, abusive, and inhumane…”3 The message portrayed them as evil torturers and savages without a conscience. Dimapur is a frontier city that tells a complex story of military occupation and violent social worlds; the spatial marks across the city highlight the experiences of people in a militarized society, who negotiate the competing authorities (insurgents, state officials, cultural associations, tribal bodies).4 Yet, vulnerable dogs in Nagaland have received more passionate support from activists in urban India than, for example, the campaigns for the repeal of Armed Forces Special Powers Act (1958), which gives Indian armed forces the right to kill Naga citizens on the basis of mere suspicion.

Conversations about animal cruelty and the practices of the dog meat trade have generated disgust and anger.5 The 2016 legal notice to ban dog meat in Nagaland became a new chapter in the battle for configuring spaces of governance, ethics and authority between citizens and dogs in India. To date, debates about dogs in contemporary India have depicted street dogs as a nuisance and a danger. In 2015, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) reported the growing ‘menace’ of stray dogs in urban India and indicated that in the state of Tamil Nadu alone more than 100,000 cases of dog bites had been registered. In the neighboring state of Kerala, dog catchers resorted to extreme measures, such as injecting stray dogs with potassium cyanide to kill them.6 No wonder that state authorities define street dogs as ‘encroachers’ in urban India and a threat to citizens. 7 Considering dog meat as part of a food system, or linking it to larger issues of food culture, taste, delicacy or pleasure, does not cross the minds of many Indians.

“Whatever they want to do”

A 2016 report brought out by the Humane Society International in India (HSI/India) noted that the consumption of dog meat was taboo in the country with the exception of states like Nagaland.8 The idea of Nagaland as an ‘exceptional state’ builds on a dominant understanding of the region as a zone of exception where people and the political state of affairs are in a permanent state of disarray and violence.9 However, given the hostility towards stray dogs in urban India, law makers proposed various methods to address the dog nuisance. In 2012, a controversial resolution was submitted by a member of the Punjab Assembly, Mr. Ajit Singh Mofar. The Congress politician proposed that all the stray dogs in Punjab should be sent to Nagaland, Mizoram or to China for, “whatever they want to do”. He further stated, “We cannot be really bothered what that is. We have to solve our problem first. Stray dogs are killing children, attacking the elderly”.10 As one might expect, this statement caused an uproar, but this would not be the last time such a proposal was made. It has been reported that state human rights commissions and local bodies, like the panchayats in Kerala, have also suggested ways to export dog meat.

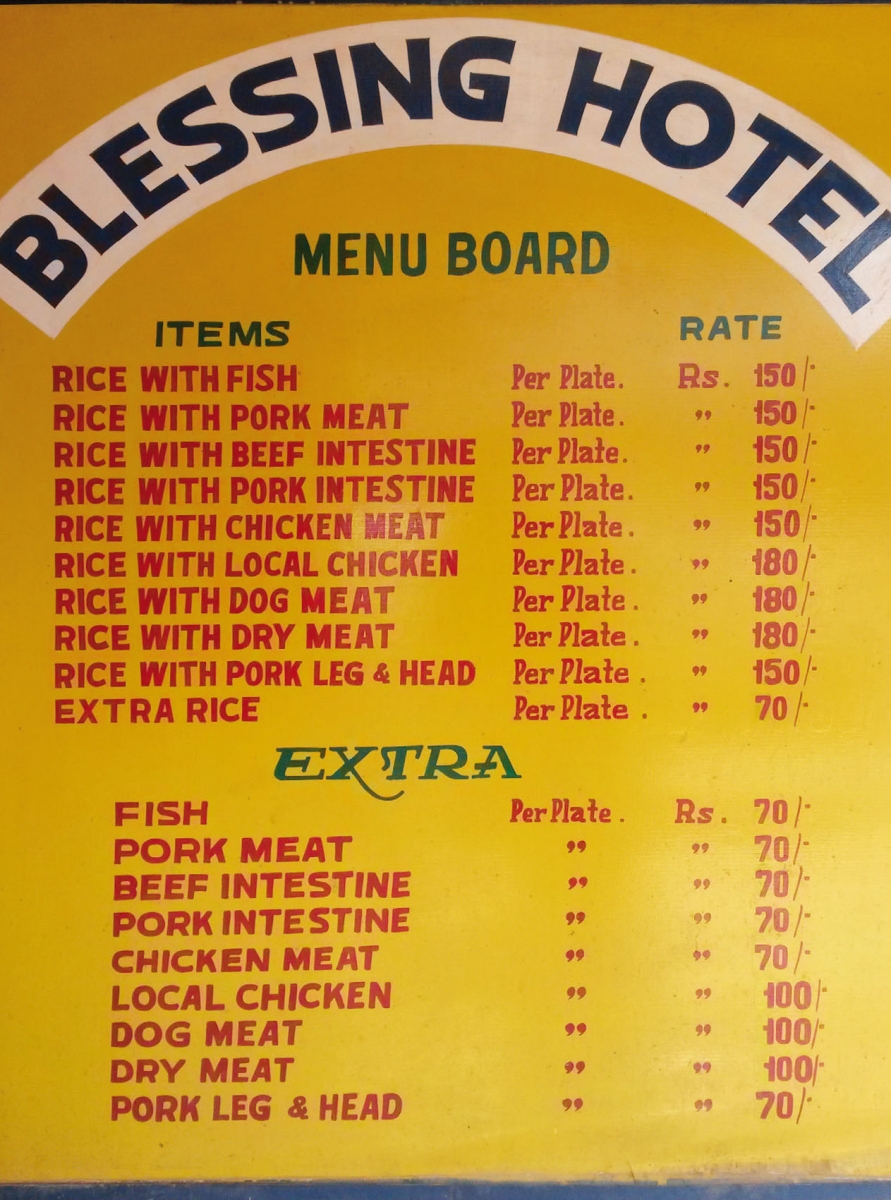

In 2016, when the Municipal Affairs Department of Nagaland requested that the Dimapur Municipal Council would oversee the matter of banning dog meat in the city, the challenges of managing a conflict city began to unfurl. There has been no municipal election in the state since 2006. The officials overseeing the municipal functions in a city of 400,000 are ad-hoc political appointees, who struggle to keep up with basic functions like garbage collection and maintenance of the sewage system. Barely able to manage the crumbling infrastructure such as water supply, drainage, and the increasing cases of land encroachments by land mafia, the municipality had little time and few resources to spend on animal welfare. Even though Dimapur Municipal Council dropped the matter and did not pursue it, a vibrant conversation did take place among the women traders who sold dog meat at the Super Market in Dimapur. “What is the point of banning?” Ms. Akhu asked me as we sat in her stall. “It sustains us. It is a question of livelihood. Just as we kill pigs, goats, and chicken, we kill the dog in the same manner.” Forty years old and mother of four children aged 12, 14, 16 and 18; all her children were in school, which she paid for by selling dog meat. For Ms. Akhu and her colleagues in the adjacent dog meat stalls, they sell a food item like any other vendor at the market. Many of them had been landless and came to Dimapur as migrants from rural parts of Nagaland. Some of them were single parents while others had partners, but were unemployed and struggled to find employment. Ms. Avani who sold frogs and herbs in her stall along with dog meat said, “We are traders. We are honest and hardworking.” She had three children and the eldest child was getting a Bachelors of Commerce from a local college. On the criminalization of consuming dog meat, she said, “By eating dog meat no one has done anything bad. They have committed no crimes like take drugs or harm the society. Even if the government bans dog meat, the customers will come and collect it from home.”11

At the heart of the debate, including the legal notice served to the Government of Nagaland in 2016, questions about dog meat as ‘food’ came up prominently. A reporter noted, “The Advocate, through the legal notice, had noted that dog meat was openly sold as food, just as chicken and mutton…”.12 Why is it that certain culinary practices are seen as cruel and savage, while others are considered appropriate in human society? Why mobilize for the banning of dog meat in India, “…which has little to no impact on the nation’s diet or commerce, and not for chicken, beef, pork… (or homelessness or crime, for that matter?)”.

Even though a large number of animals in our food system are subjected to cruelty in India, the call to ban dog meat is a strategic one. According to Desoucey, “the answer depends on who those groups are and where their interests lie. What these questions imply is a more intricate set of relationships among what we value, what we say we value, the vulnerability of various targets, and what we, as individuals and as members of society, are actually willing to fight for”.13 In this context, the connection between dog and human is considered to be a long-lasting and deeply social one. Revered as a companion, friend, caregiver, and a member of the family, humans have developed strong attachments to their pets, particularly dogs and cats. These emotional conditions, according to Archer, prevail because, “people usually view their relationship with pets as similar to those they have with children. Pet owners treat pets like children”.14

Dog culture

The moral issues connected to the consumption of dog meat have had far reaching consequences. A Naga migrant who worked in a retail store in New Delhi told me that she ate her lunch alone after she had been regularly humiliated by her colleagues about the dog eating culture in Naga society. “One day I was so angry I told them yes, yes, we also eat human beings. We are cannibals!” Consumption becomes connected to the identity and culture of the consumer. During a conversation in July 2016, about the proposal to ban the sale of dog meat, the president of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty against Animals (SPCA) Dimapur District, Mr. N. Joseph Lemtur said, “It is not being taught from the school or church, it is cultural. We have become habituated to eat dogs; this is very unlucky. So at this juncture, animal activists like the SPCA are campaigning against it”. It is important to recognize how the culture card is applied to legitimize certain practices, and that homogeneity is carelessly assumed among a cultural group. However, the reality is that a large number of Naga households do not eat dog meat, and many more refrain from eating wild animals, silkworms, water insects, ferns and mushrooms, all considered to be delicacies in Naga society. Nevertheless, the ongoing debate about the consumption of dog meat is framed by cultural practices, and ideas about civilization and cruelty.

Dogs mean different things in Naga society: pet, companion, food, medicine, guard, spirit sensors, thief catchers and cat chasers. They also feature centrally in the most famous origin myth about the Naga script, which is connected to identity and language. According to legend, a dog ate the Naga script written down on animal skin, and from that day onwards, Naga tradition and knowledge has only been received and shared orally. The relationship between dogs and people in Naga society is an intimate one, and is integral to everyday lives. Dog meat has been part of Naga cuisine for a long time, yet, before dishes started to appear on restaurant menus and before vendors starting selling the meat in the market place, there was no debate or national campaign to ban dog meat.

In contemporary India, the language of animal rights that triggered the dog meat debate is strongly rooted in a framework of class and caste.15 Unlike the cow, which is regarded as holy and therefore banned as a food item in some parts of India, or the tiger and Amur falcon campaigns based on saving the animals from extinction, the dog debate rests on a framework of care and love. This is leaky politics. This debate about eating man’s ‘best friend’ is a moral minefield where meanings of acceptable dietary practices are fluid and ambiguous and the logic of barbarism is juxtaposed with love and compassion.

Who is best capable of loving the dog? What are the dilemmas for dog meat eaters? The politics around which animals deserve protection has become an arena to discuss issues of ethics and justice between humans and animals in India. It is predominately an urban issue. Concern about stray animals, selling certain meats in public view, and animal welfare generally appear when an urban area is desperate to clean up its act; to be taken more seriously as a place for investment, tourism, and in the case of Dimapur, peace. The exceptional attention dogs have received in urban India as vulnerable beings, in comparison to squirrels or monkeys, tells us about the distinct language of value in metropolitan India. In this language, dog meat betrays a civilizational deficit. It reflects notions of a far off place where ethics, justice and care are lacking. For authorities in Nagaland there is an aggressive drive to sanitise the city of pests like stray dogs as part of a general mindset of being more metropolitan; more like other cities in India. And while passionate activists stand up for vulnerable dogs, extraordinary laws like AFSPA leave the armed forces with the right to kill and detain human dwellers of the city and throughout Nagaland and other parts of the frontier. If dog meat does symbolize cruelty on the one hand but also a part of local food habits on the other, perhaps a useful way to think about its place in the city is to consider the women traders at Super Market, who not only depend upon the dog meat trade but who have the most realistic sense of demand; a demand that will continue even if banned in public.

Dolly Kikon, University of Melbourne (dolly.kikon@unimelb.edu.au).