ហៅព្រលឹង Hau Proleung: Calling Our Collective Souls Home

The human body is a shell for the soul. It is a Khmer cultural belief that this body contains 19 different proleung – spirits or souls – connected to different parts. Unbeknownst to the keeper, when one navigates a life transition, personal hardship, illness, trauma, or anything that might rock one’s stability and foundation – the proleung may wander and be left behind somewhere. This necessitates a Khmer ritual called Hau Proleung to call the soul(s) back and reintegrate what was lost. 1 The keeper may never be the same, but calling the soul back is a spiritual reunion with, and a mirror that reflects, the version of self that was present during that specific point in time. The keeper recognizes the figure in the mirror and affirms their experience, welcoming them to come back home to oneself.

This opening introduction to my multimedia storytelling project ហៅព្រលឹង Hau Proleung: Calling the Soul is a dialogical exchange that I believe is symbolic of the Khmer diasporic experience. 2 Khmers across the diaspora have lost parts of their proleung, whether consciously or otherwise.

April 2025 marks 50 years since the United States’ imperial ambitions in Southeast Asia brazenly exacerbated the displacement of thousands of Khmer, Lao, Vietnamese, Iu Mien, Hmong and other Southeast Asian diasporans to scatter across the world by carpet-bombing our homelands into smithereens – aiding the same communist movements into power that they sought to destroy. Though the impact of US imperialist foreign policy in Southeast Asia could be the sole focus of its own piece – I frame this article with the most basic assumption that US foreign policy decisions during the Cold War era made an ineradicable impact on the future of Cambodia, its citizens, and their descendants. And we are still reckoning its total cost today.

Fig. 2: Sok Sabbay Tham Phaluv by Janhtria Sapearn. Digital exhibit artwork, Wing Luke Museum, 2023.

It’s been 50 years since April 17, 1975 – the beginning of an almost four-year genocidal regime led by the Khmer Rouge – and a day that has been memorialized in the blood of the Khmer diaspora, its impacts still present and imprinted intergenerationally in the psyches and physical shells of our people.

The further loss of both our collective and individual proleung is perpetuated when we are unable to name our truths and integrate the missing pieces of our history to build a shared foundation on which we can move forward.

We have many scholars to thank over the decades for the abundance of research uncovering the harrowing facts – but most pressing for me to highlight right now are the 1.5- 3 and second-generation Khmer healers, authors, and artists who are carrying forward the torch to heal from this past. Through the lens of a collective remembrance of our power, we are calling upon our courage to hope, to dream, to resist, and to survive. So how do we remember this past without letting it become the end or the beginning. How can such remembrance become a moment in the history of our diaspora’s evolution? No matter which side you were on, everyone lost someone; everyone experienced movement and migration, whether within the country or outside of it. What is our responsibility to heal from the past to look forward to the future, educating our descendants of our true histories as a dialogical process of calling our hearts and souls back to ourselves?

Sok Sabbay Tham Phaluv សុខសប្បាយតាមផ្លូវ

The histories of Khmer peoples’ migration across the globe in search of refuge is varied across time and space – no two stories are alike, although there are common threads. It was within this pre-text that a group of Seattle-based Khmer artists – Sophia Som, 4 Bunthay Cheam 5 , and me – dreamed up and materialized a multi-disciplinary storytelling project in partnership with the Wing Luke Museum 6 : Sok Sabbay Tham Phaluv: សុខសប្បាយតាមផ្លូវ [Fig. 3]. The project title – which translates into English as “May you be well and happy on your journey” –is a Khmer prayer or well-wish that is often shared between people upon departing. This supplication is bittersweet, as many have been forced to journey away from their homeland and build a new life elsewhere, becoming members of the diaspora. So, what then does it mean to be a member of the Khmer diaspora? What histories unite us? Divide us? What is home, and where do we find home? What is in our collective consciousness to heal in this lifetime?

Fig. 3: Bunthay Cheam, Sophia Som, and Darozyl S. Touch at opening exhibit of Sok Sabbay Tham Phaluv, Wing Luke Museum. Photo by Dene Diaz, 2023.

We explored these questions and more through the original curation of interviews, archives, photographs, and videos to tell uniquely different stories about the Khmer diaspora – filled with vulnerability, curiosity, and hope for our collective futures. Our exhibit showcase took place during the time of Pchum Ben in October 2023, a two-week period in which Cambodian Buddhists give offerings at the temple to commemorate the ancestors who have passed on. Not only is Pchum Ben a time for collective mourning in which we grieve and commemorate our ancestors. It is also a time for us to honor and take stock of their paths that paved the way for the journeys that have yet to be – and to recognize the power we may draw from, as the living.

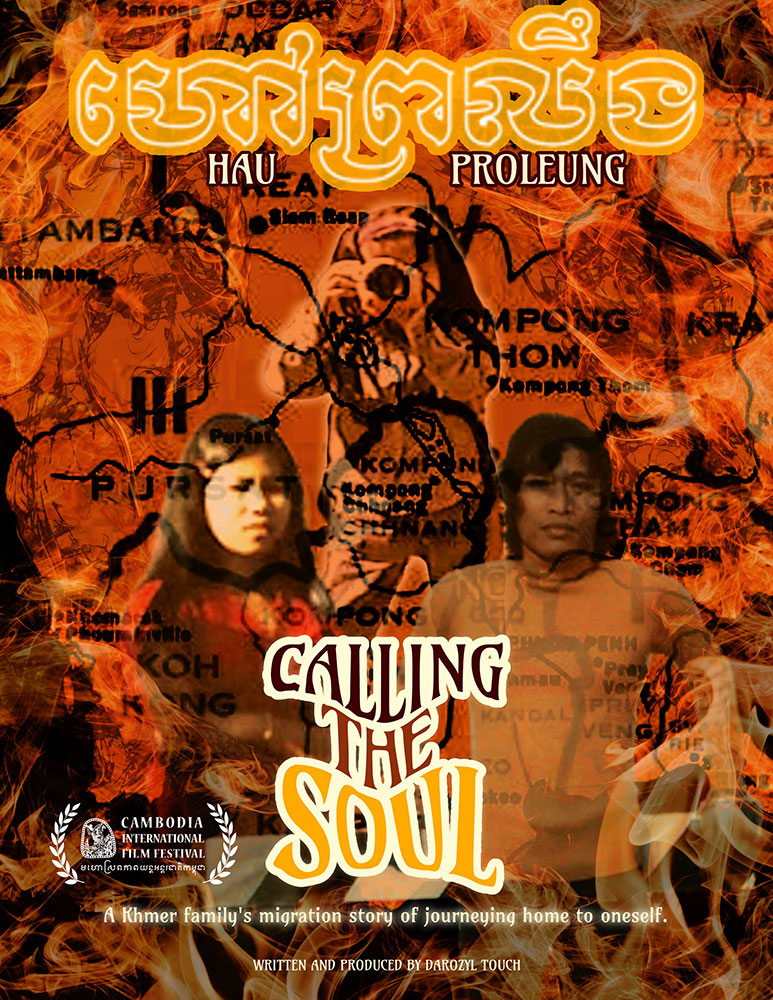

My related film project, Hau Proleung: Calling the Soul, was created as an homage to the diasporic courage, bravery, and resiliency of my parents and millions of other Khmer peoples’ will to survive, so that we – the generations beyond – may have a chance to thrive [Fig.4].

Fig. 4: “Hau Proleung: Calling the Soul” by Darozyl S. Touch. Film poster, 2023.

ហៅព្រលឹង Hau Proleung: Calling the Soul

In recovering a treasure trove of home video tapes and priceless archives, this project – or rather, journey – was already in the making 26 years ago during my first trip to Cambodia with my parents. In 1999, my father was faced with a terminal diagnosis of Stage IV Liver Cancer with a prognosis of less than a year to live. My mother took a leave of absence from work, and my parents collectively decided to spend that “last” year traveling as a family to journey back to their homeland – a place from which they had been torn through the ravages of war and genocide. They sought to educate me and traveled to the places that brought them memories of profound joy and, on the other end of the continuum, immense grief. Stories surfaced about what was left of the house my mother was raised in before they were forcibly displaced; where my father was one of two survivors in an ambush at the Khmer-Vietnamese border; the Kamping Puoy “Killing Dam” where my mother was separated from her family and forced to labor as a teenager; and so many more. Through an online exhibit in the form of two spatial timelines mapping locations significant to my parents, digital art pieces, poetry, and archival materials, a physical exhibit at the Wing Luke Museum, and an accompanying short documentary film, Hau Proleung synthesizes the complex histories of my parents’ migration to the United States, delving into themes of death, rebirth, and transformation. The project is an expression of the depth of grief and loss on the continuum of unconditional love.

Through their stories, I wanted to illuminate the experiences of members of the Khmer diaspora and their migration journeys as they sought refuge in new lands from the civil war and genocide in Cambodia. What happens to a people when they are forced to leave their homes? How does their identity grow, evolve, shift, adapt to root in their new context? What parts of themselves, their identities, their histories, their experiences did they leave behind or repress to move forward? What must we collectively go back to recover to move forward?

My father left behind a personal archive. This included a journal he kept during the Cambodian Civil War (1970-1975) and during his brief time in a refugee camp in Chanthaburi, Thailand following the ascension of the Khmer Rouge. It also included letters written when he was living in the Camp Pendleton refugee resettlement camp in San Onofre, California and Fort Chaffee resettlement camp in Arkansas. As I pored over my father’s archive, stories began to materialize and connect in a way I couldn’t have imagined. I grieved for years thinking that all his history was lost when he died, but I came to realize that he had prepared me as well as he could with the items he left behind to find and connect the missing pieces.

One Hi8 videotape was the missing puzzle piece. In my quest to digitize the tapes, I unassumingly found the very last video recording my father left: a video in which my 11-year-old self recorded my father sharing unknown parts of his life history, giving his last words of advice to me, and offering one of his last wholesome conversations with my mother, in which he apologized for leaving her with the soon-to-be responsibility of raising a child on her own. The first time I laid eyes on that video, almost 20 years after it was recorded, it clicked for me that his audio would be the narration of his migration story in the short documentary I created. Meanwhile, my mother’s story would be narrated by my interviews with her as she rewatched these home videos for the first time in decades.

Finding these treasures was like calling my soul back home to myself – uncovering parts of me I didn’t know were missing. By reconnecting to these materials, I was intuiting on a deeper level the ancestral wisdom that was coming to surface about my parents’ own untold stories. I floated through this energetically charged sea of emotions that consumed me for over two years of my life.

Soul Reflections

Two scenes from both the film and the exhibit so poignantly demonstrate this process of “Hau Proleung,” or calling the soul back, through my parents’ stories of returning to places in which they experienced great harm.

In 1999, my mother returned to Kamping Puoy Lake (also known as the “Killing Dam”) – a human-made lake whose dam was constructed by thousands of forced laborers including herself – for the first time since 1979. Upon her return, she noticed the many visitors who frequented this dam and lake as a site of leisure – a site that she was forced to build with her own hands as a teenager, digging trenches one meter wide and tall each day while on the brink of starvation, many around her dying in the course of its construction. It was peculiar for her to see children and their families laughing while cooling off in the waters – to even see her own child laughing and playing in the waters – of a human-made lake that was soaked with the blood of the deceased. I created a visual piece from a photo my father captured of her looking out at the water, juxtaposed with her staring out at an apparition of her teenage self [Fig. 5]. 7

Fig. 5: “AQUEOUS EXCHANGE” by Darozyl S. Touch. Photograph manipulation, 16”x12”, utilizing photographs from 1982 and 1999. Wing Luke Museum, 2023.

The image caption is a tanka describing the stories the water exchanges with her:

“I wonder if you

Recognize me standing here

Mourning that we’ve seen

The worst in humanity

And still have power to love.”

In my father’s collected journal entries (written in French) he recalls an ambush he survived, in which I was able to cross-reference his audio retelling of this story from his last video message, in addition to video footage I found of him revisiting significant battle sites in Svay Rieng with his old military friends for the first time since he left Cambodia in 1975. 8

This moment was elucidated through one particular image of my father and his comrades laughing, drinking, and celebrating – juxtaposed with his journal entry recalling events from 1974 [Fig. 6]: -

Night of 26 to 27/03/1974

Explosion at 410BC (“battalion chasseurs” or infantry battalion), but I escaped it completely.

There remains only:

—the commander of 410BC

—a nurse

—one troop

—and me

friendly losses:

—30 killed

—15 wounded

losses:

—97 M16

—1 machine gun 50 (trans. note: 0.50 caliber)

—2 81mm mortars

—2 60mm mortars

—2 AN/PRC-25 radio sets

and other things”

The haiku caption of this visual piece reads:

“I look left and right

And wonder if they’ll return

Or if I will, too.”

Fig. 6: “PAWN” by Darozyl S. Touch. Photograph manipulation, 10”x8”, utilizing undated photograph (est. 1973 or 1974), and March 1974 journal entry. Wing Luke Museum, 2023.

Of the many tragic sentiments conveyed in this March 1974 journal entry, the most striking to me were the non-human “losses” my father recounted – weapons, artillery, and equipment that perhaps were purchased with the last bits of US government aid before Congress halted all funding in 1973, and further shifted the tides toward the Khmer Republic’s demise. I wondered: how did my father re-experience these losses when he learned in more detail of these macro-level foreign policy decisions after fleeing to the United States, while reconciling that he survived a traumatic moment that also served as a testament to the felt global impact of those policy decisions at the micro-level? I’d imagine his cognitive dissonance to be consuming.

Both scenarios facilitated a recognition of and reunion with parts of them that necessarily had to be left behind to survive. The grief, the loss, the fear – if present – could not outweigh their will to survive in their younger selves. As my mother often stated in her interviews, she did not have the time to fully feel the breadth of the emotions that were swelling within her without the risk of dying. Now that they had triumphed against the odds, returned to these sites to recover their missing pieces, what did they see of themselves that they weren’t allowed to before? What did they feel as they looked into the mirror, seeing their past, present, and future in the same reflection?

Collective Callings

It was a blessing for me to screen my documentary in Seattle, Washington, and in Phnom Penh at the 2024 Cambodia International Film Festival eight months later. I found that it truly was a healing and diasporic awakening experience for audience members to hear some of their individual families’ stories told through the lens of my parents. They felt seen and affirmed as 1.5-, second-, and third-generation children who too were trying to do the work of preserving their families’ histories. There was a resonance across audience members who also understood my film as a cautionary tale about the consequences of keeping these stories locked inside. In my artistic decision to walk the audience through my family’s journey of healing grief through the reunification of self, I showed the vulnerabilities and mortality of humans who defied death itself but could not escape the weight of coping with that triumph. PTSD and addiction – as shown through my father’s story – has the power to triumph at times. Consequently, what is our responsibility as the next generation of healers, artists, and educators to hold space for our elders, our peers, and ourselves to reckon with the complexities of calling our souls back? Especially when memories are filled with skeletons of the past that may be better off rotting in those rice paddies they traded for concrete jungles.

Fig. 7: Author receiving a Khmer Buddhist water blessing following a spiritual ceremony in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Photo courtesy of Darozyl S. Touch, 2012.

It's precisely the stories of how they survived against the odds that remind us of our collective power and right to transform from the state of surviving to thriving and reverse the long-term physical, psychological, and spiritual impacts of historical trauma [Fig. 7]. These stories illuminate that whether missing proleung or not, and despite inheriting intergenerational trauma, we are descendants of a spirit that is unbreakable, for our very existence – somewhere in our ancestral lineage – is against the odds. As my mother stated in her interview, “You have to be brave.” After all, as she put it, it is only “because of the power of the Universe that I am alive today.” I take that and the work that I create as a call to action to make every breath count, to be a seeker by calling our souls home for Khmer people to heal forward into the future.

Darozyl S. Touch holds space for people to reclaim their power as a second-generation Khmer American educator, cultural artist, and healer – weaving Khmer ancestral knowledge, storytelling, plant medicine, and the transformative power of collective grief work in service of our intergenerational healing for a liberated future. She is also an Assistant Dean for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice in Seattle University’s College of Arts and Sciences. Email: darozyl@nearyalchemy.com